Alpine Tips

How to attach a rappel ring to a sewn sling

It might first appear like a bit of rope sorcery - How can you attach a rappel ring to a sewn runner? Each one of them is a closed loop! Read and learn, young Jedi.

Post update: This is NOT a recommended method! It’s easy for the ring to come off the webbing and for the anchor to fail.

It's mentioned because it might be one of your only options, or you might come across an existing rappel anchor with a ring attached like this. You should be aware how it got that way, and the potential for it to become easily detached.

Try this yourself, see how easy it is for it to come undone.

So, although I've kept the original post below, I no longer think it is such a nifty trick. I’ll stick with leaving a carabiner behind, or second choice, a quick link.

My partner and I were heading down the West Ridge of Forbidden Peak in the Washington Cascades.

A series of rappel anchors in various states of disrepair were leading us steadily back to our camp.

When we got to one rat’s nest of several ancient but serviceable slings around a boulder, my partner looked at it with a critical eye and said, “Hey, let’s take a sec to beef up this anchor. I’m going to add a rappel ring to the best looking one of these slings.”

I paused, thinking, then said, “Don't you need some webbing too, so you can thread it through the ring and add the webbing to the anchor?”

He looked at me like I had rocks in my head and said, “Duh, no, I’m just going to add the ring to the webbing that's already there.”

I looked back at him, even more confused. “How are you going to do that!” I demanded. “The ring is welded shut, the webbing is tied shut, and you’ll never untie it without pliers!”

He looked back at me, and shook his head with a little laugh. “Watch and learn, young Jedi, I'm about to show you a little trick,” he said.

The anchor looked something like this . . .

source: summitpost.org/nice-rappel-anchor/906562

Now, if you already know this little move, you're probably going to be laughing at me. That's OK, I can handle it.

A little backstory. I’ve never been much of a fan of carrying rappel rings for alpine climbing. Sure, a rap ring gives you a nice smooth pull with less chance of the rope end hanging up.

But, for alpine climbing on an established route, where you’ll often find a tangle of pre-existing slings, I used to think carrying a rap ring was silly, because you couldn’t thread it through the slings that were already in place.

Given that situation, my usual choice was to take the oldest looking carabiner on my rack, clip it to every strand of the webbing, then close the carabiner gate with some tape to make a “cheapskate locker”.

Or, I’d occasionally carry a quick link, a threaded link of chain that can be opened, attached around multiple strands of webbing, and then closed up. But, this is a rather heavy and single use piece of gear, so I would usually sacrifice a carabiner.

I learned a 3rd option that day on Forbidden, when I saw this little trick for the first time. It almost looked like a magic trick when my partner showed it to me for the first time, because I had it so firmly in my little head that a closed circle ring could not be threaded through a closed circle loop of webbing.

Well, technically it’s NOT threaded through the webbing, but attached via a simple girth hitch. This attaches the ring in a couple of seconds to a closed loop.

(Yes, I know some anchor engi-nerds are having a minor freak out right now and screaming “don’t you know girth hitching a sling decreases its strength by 30%”, blah blah blah. 11/16” webbing is rated to about 13 Kn, and the maximum possible force on a rappel is about 2 Kn, so I’m not worried about this in the slightest.)

And where did I get those numbers? From the climbing gear strength ratings post, which you can read right here.

UPDATE: Strong note of caution: Easy ON also means easy OFF!

Meaning, if it takes you a second to attach this with a girth hitch, it's also going to take a mere second of inattention for this to potentially come off, or worse yet, come halfway off, without you noticing it.

After I first published this post, I got an email from a climbing friend. He told me a scary story about setting up a rappel on this exact situation, with a girth hitched rap ring. While he was getting rigged up, the runner got a little cockeyed. He was a moment away from leaning back on the ring when he realized it was completely unattached to the webbing, YIKES!

Here's another accident report from Cutthroat Peak in the North Cascades of Washington in April 2024. Suspected cause is girth hitched rappel ring. Here's the accident report.

(Yes, best practice is to load test the masterpoint with a tether backup in place before you commit to it. But sometimes with darkness, stress, distractions, whatever, that doesn't always happen.)

Here are three much more secure options for alpine rappel hardware: the cheapskate locker, a.k.a. taped gate carabiner, a quicklink, and a rappel ring that’s actually tied through the cord, instead of being girth hitched.

When properly placed, it is impossible for the hardware to come off of the cord.

So, after all that, if you still want to girth hitch a ring onto cord or webbing, here's how to do it.

Closed loop of webbing and rappel ring.

Pass a loop of webbing through the ring.

Tuck the webbing loop behind the ring.

Pull it tight. Done, and ready to rap. Be SURE and double check this before you go.

Be sure and run your rope through the bottom part of the ring and not the top!

If you don't like the looks of it, don't be a cheapskate, trade it for a carabiner.

Once more, for emphasis: if you clip the top of the ring in the photo below, seriously bad things are gonna happen!

Speeding up a group rappel

Does your larger climbing team have two rappels ahead to make it to safe ground? Here’s a simple way to speed up the process.

Scenario: You’re descending a route with a team of four, and you have one rope. You get to the rappel spot, which requires two raps on a single rope to get down to safe ground.

Standard practice would be to have everyone rappel on two strands to the next station, and then have everyone rappel again to get to the ground. For your team of four, this means eight total raps . . . and a lot of time.

Consider this alternative:

Fix one end of the rope at the top.

Have the first three people rap to safe ground on a single strand.

The last person (a more skilled team member) unties the fixed rope end, pulls up half the rope and threads the anchor as for a normal two-strand rap. Then, this last person raps to the intermediate station and then finally to the ground. This results in a total of five raps rather than eight, speeding up your team’s descent time.

Be sure everyone on the team is comfortable rapping on a single strand, and add some extra friction to the rap if necessary. See this tip on more ways to add friction to a rappel.

Two good reasons to mark the middle of your rope

There's two good reasons to mark the middle of your rope. One is hopefully pretty obvious, the other one not so much, but perhaps more important.

There's two smart reasons to mark the middle of your rope. The first one might be rather obvious, the second one perhaps less so, but it may be more important. Let's have a look at both.

1 - Setting up a rappel

Knowing with certainty that the middle of your rope is at the rap anchor is a Good Thing. Of course, if you cut off the end of your rope for any reason, this middle mark becomes less accurate. But that is pretty darn rare, so a permanent mark on your rope should last you for a long time.

Yes, you can do the trick of measuring hand spans to find the middle of your rope, which actually is pretty darn accurate, but having a middle mark makes it idiot-proof.

2 - Belay Safety

This is one people may not think about right away, but it’s arguably more important. For decades, pretty much everyone climbed with a 50 meter rope, and you would never find a single pitch sport climbing anchor more than 25 meters off the ground. But many newer routes are longer, requiring a 60, 70 or even 80 meter rope. Because these long routes are generally newer, they may not appear in a guidebook, and there's often not a reliable way to tell at the base of the route precisely how long it is.

If you’re belaying the leader, and you notice the middle mark of the rope pass through your belay device before the leader has reached the anchor, that should ring a LOUD alarm bell in your head! You're not going to have enough rope to lower them off and reach the ground, and you need to figure out a crafty solution to a potentially serious problem.

A quick review of the report/book “Accidents in North American Climbing”, published annually by the American Alpine club, can confirm that this is a recurring problem. One likely cause is the increase in the number of routes that require a 70 meter rope, as mentioned previously.

Another contributing factor is probably more gym climbers venturing outside. In a gym, routes are almost always less than 30 meters tall, and therefore the 60 meter rope that many gym climbers have for leading is guaranteed to be long enough.

While many people climbing single pitch routes from the ground don’t bother tying into the end of the rope or even having a stopper knot, doing either of these simple fixes eliminates the problem of potentially dropping your leader when you’re lowering them off.

(Even if you have a 70 meter rope for a route designed for it, if those anchors are close to 35 meters off the ground, and the belayer decide to back up a little bit, that could still cause you to end up short when you’re lowering. So, just having a 70 meter rope doesn’t necessarily eliminate the problem.)

So, how best to mark the middle of your rope?

There's been a L O N G debate on the interwebs about the safety of using things like Sharpie pens and laundry markers to mark the middle. We’re not going to rehash those here.

An excellent choice is to go with a designated rope marker made by the French company Beal, one of the largest rope manufacturers in the world. It’s inexpensive and has a specially formulated ink in a handy dispenser that's designed for climbing ropes. Get one, use it, and share the extra ink with your friends.

Beal rope marker

If you want to make a quick temporary mark, find the middle of your rope and then put some tape on it if you have some. This is a short term solution, because it doesn't pass through a belay device very well and can fall off.

Summary:

If you’re leading a lot of sport routes outside, you probably want a 70 meter rope, which is pretty much the new standard.

Put a middle mark on your rope if it doesn’t have one. Use it to set up rappels and also for belay safety.

Use the generally accepted best practice of a closed rope system. For toproping, this means the belayer is either tied into the end of the rope, has a solid stopper knot tied into the end, or has the end tied to something reasonably heavy like a backpack. to avoid any chance of dropping the leader when lowering.

Think you’d never make a mistake like this? Well, if it can happen to Alex Honnold, it can damn sure happen to you.

In 2016, Alex was dropped by his belayer because they were using a 60 meter rope on a 70 meter route, there was no knot in the end of the rope, and his belayer was not tied to the end of the rope. While she was lowering Alex, the end of the rope zinged through her Grigri and Alex fell onto some “gnarly rocks”.

Would a middle mark have prevented this accident? Hard to say. But it would not have hurt anything.

Read the complete accident account here, from “Accidents in North American Climbing”, an annual publication of the American Alpine Club.

Below is a copy paste.

I had run up the route Godzilla (5.9) to put up a top-rope for my girlfriend and her family. At the last second her parents asked us to hang their rope instead of ours. I didn't think about it, but their rope was a 60m and mine was a 70m. I was climbing in approach shoes and everyone was chatting at the base—super casual, very relaxed. As I was lowering, we ran out of rope a few meters above the ground and my belayer accidentally let the end of the rope run through her brake hand and belay device.

I dropped a few meters onto pretty gnarly rocks, landing on my butt and side and injuring my back a bit (compression fracture of two vertebrae).

Analysis

Lots of things should have been done better—we should have thought about how long the rope was, we should have been paying more attention, we should have had a knot in the end of the rope. I wasn't wearing a helmet and was lucky to not injure my head—had I landed on my head, it probably would have been disastrous. My belayer had been climbing less than a year. Basically, things were all just a bit too lax. (Source: Alex Honnold.)

Easy way to pass the knot on a single rope rappel

It’s rare, but you might someday find yourself having to rappel two full rope lengths on a single strand. Here is a simple, fast and unconventional way to get past the knot.

This tip was written with the help of Bryan Hall, who is certified by the Society of Professional Rope Access Technicians (SPRAT) at their highest level.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

Short version:

You’re rapping on two ropes tied together in a single strand, and you need to pass the knot connecting the ropes to make it all the way down. (For some scenarios when you might need to do this, keep reading.)

Solution: Tie a butterfly knot just above the knot connecting your ropes. Use the butterfly loop as a ready-made clip in point when you’re passing the knot.

We're trying to keep it simple in this example, so we’ll assume you're on something less than completely vertical or free hanging terrain. On something less than vertical, you can momentarily “batman” down the rope to reattach your device as shown below, and hopefully also step up for a moment to unclip your tether.

If things are completely vertical, it gets a bit more complicated, more on that below.

What about passing the knot if you have a standard double rope rappel? Well, with some knowledge of Crafty Rope Tricks, you should pretty much never have to do this! Learn more at this article.

When might you need to rappel on two ropes tied together in a single strand?

You’re between one and two rope lengths up on a climb, and you have some sort of emergency situation: injured person, incoming lightning storm, impending darkness, whatever, and you just want to get to the ground ASAP and leave your ropes to get later.

You have two or more rope lengths below you on moderate terrain (4th class rock; steepish snow) that at least one person on your team is comfortable downclimbing without a rope. You send your whole team down on the two ropes tied together. The last person unties the rope, tosses it, and solo downclimbs. (or “downleads” by cleaning gear left by the next to last person. (Learn more about downleading here.)

You’ve fixed two or more rope lengths up to the high point on a big wall, and you’re rapping back down to the bottom. In a day or two, you’ll come back, ascend your ropes, and continue with the route.

You’re descending fixed ropes that someone else set up, like descending from Heart Ledge, Sickle Ledge or the East Ledges on El Capitan.

Anyway, those are some not-so-normal-but-entirely-plausible scenarios where you might need to pass the knot on a single rope. Can you think of any others?

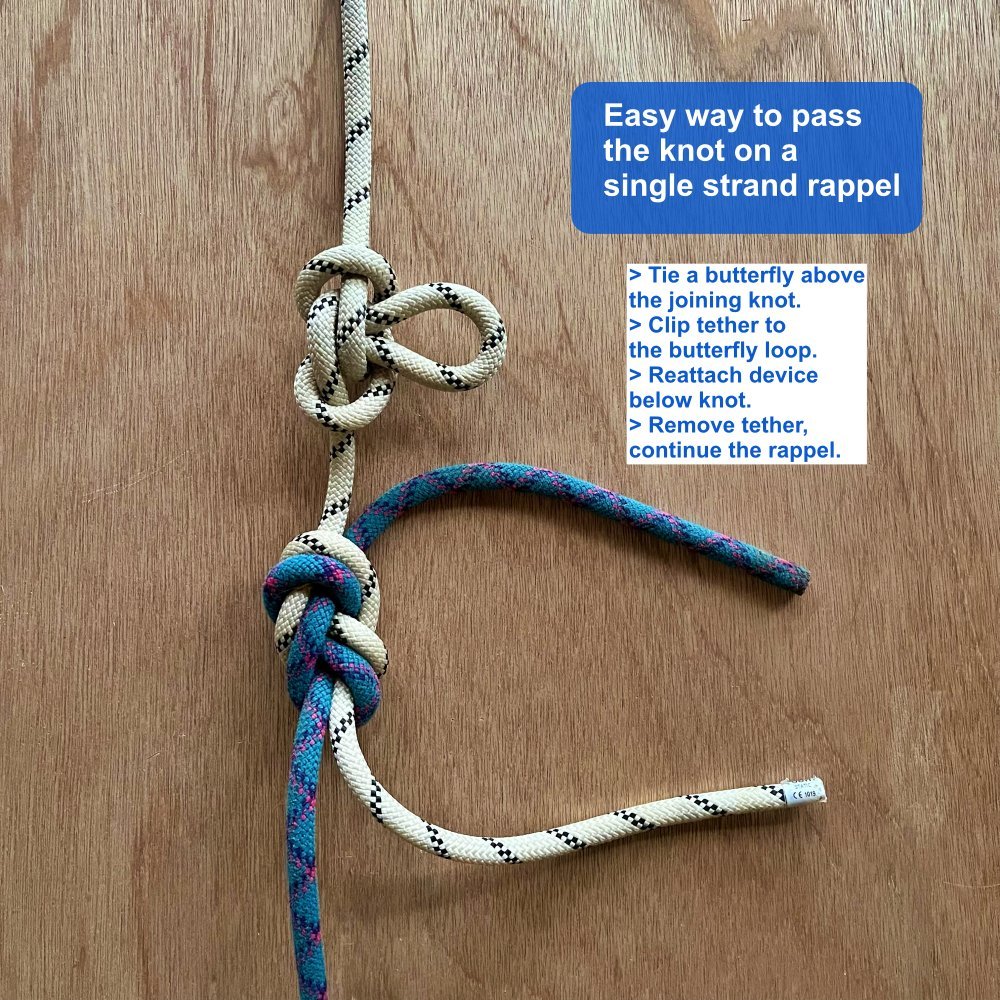

Two ropes connected with a Flemish bend, with a butterfly loop in the “upper” rope so you can safely pass the knot. Try to tie this butterfly as close to the Flemish bend as you can.

The butterfly is one option; any bight knot will work. The Flemish bend is preferred for a single strand rappel over the flat overhand bend, which is a standard for rappelling on two strands.

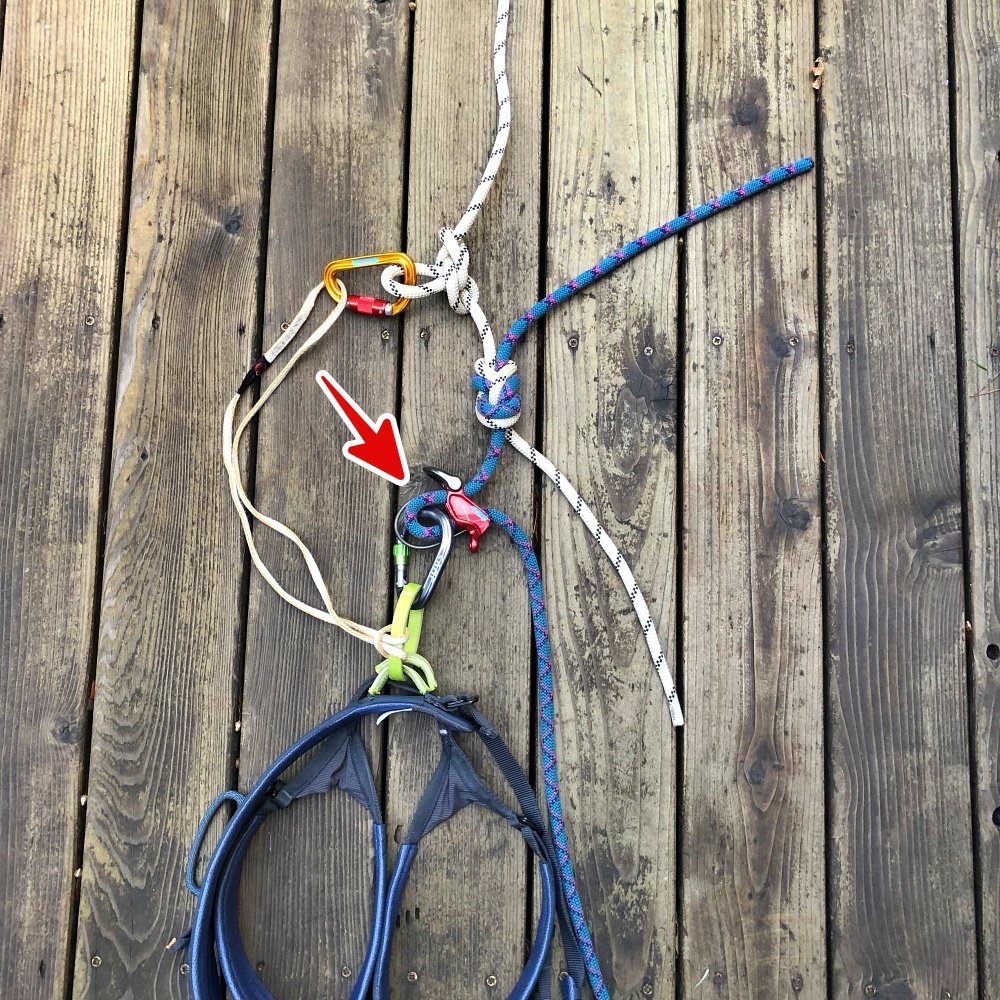

1) Before you start down, girth hitch a clip a short (60 cm sling or PAS) tether to your harness, and clip it with a locking carabiner. Rappel down the upper rope, and stop when you get just above the butterfly.

2) Clip your pre-tied tether into the butterfly loop; remember to lock it. Nice, you're now secured to the upper rope with your tether.

3) Remove your rappel device from the upper rope. Yes, this will require you to get some kind of stance for your feet to unweight the rope a little bit. (If this steep or you're scared, you could tie a catastrophe knot in the bottom rope and clip it to your harness as a backup.)

4) Downclimb or “batman” down the rope until you're below the joining knot. Reattach the rappel device to the bottom rope.

5) Unclip your tether and continue with the rappel. Schweeet, you just passed the knot!

Typically, this is set up with just a knot connecting the two ropes, such as a rewoven figure 8 bend, also known as the Flemish bend, or simply a flat overhand bend.

Sure, these knots are safe enough, but it sure doesn’t give you any assistance when you need to get past the knot. This is the beauty of adding the butterfly loop - you have a ready-made, secure point to attach a short, repeat, SHORT, leash to add an instant safety when you’re transferring your belay device from the top rope to the bottom rope.

This process is MUCH easier if you can find a small stance for your feet so you can momentarily take your weight off your rappel device. This should typically be possible on steep snow, ice, or low fifth class rock.

If you’re trying to pass a knot on a completely free hanging rappel, things get more complicated. You typically would add a friction hitch or ascender above the knot, weight that, remove your rappel device and reattach it below the knot, unweight the friction hitch / ascender, remove it, and continue rappelling. If you find yourself having to do this in a very steep terrain, you’re probably a caver or big wall climber, have an ascender, aid ladder or other helpful gear, and have already practiced this technique. Even so, the butterfly knot can still give you a handy place to clip for additional security.

What about using a flat overhand bend on a single strand?

If you use a standard flat overhand bend here instead of the Flemish bend or a more robust knot, you're probably gonna be fine. However, it's not best practice for a single strand rappel. Here's a much longer article examining this issue.

Safety note: keep your rope tails about 30 cm

Typically, when tying two ropes together for a rappel, you tie the knot with long tails, at least one foot. Some folks do it closer to two feet (the extra length doesn’t make them any safer or stronger, but it might add a little psychological boost.)

However, anytime when tying two ropes together like this, you want to AVOID using very long tails. Reason: the person rappelling could make the fatal mistake of reattaching their belay device onto the tail(s), instead of the actual rope. Yes, it has happened. It probably sounds like a mistake you would never make if you’re reading this indoors on a nice sunny day, but if it’s at night, raining, in a cave, you’re physically and mentally fried, whatever, simple mistakes like this can happen all too easily.

Here's a longer article on this topic.

The better practice is:

Tie your knot to connect the ropes, and keep the tails about 30 cm / 12-16 inches max (or, about the length of your forearm.)

Tidy the knot properly, then snug it down (aka “dress it and stress it.”)

Stuck rappel rope? Try the “rubber band” trick

Yep, stuck rap ropes suck. But there are a few Crafty Tricks to help you solve this.

You start to pull the rap rope, but can’t get it moving. Try a few tricks before you descend into utter despair.

You and your partner grab opposite ends of the ropes and pull, hard. One of you keeps the “pull” pressure on, while the other suddenly releases her end. The “rubber band” effect of one end of your dynamic rope “springing” upwards often will get a stubborn rope moving.

You can also do this with a Grigri or similar belay device. Crank as much tension as you can on the rope through the Grigri, and then pull hard on the handle to open it. The release in tension might be enough to free your rope. (This clever Grigri tip is from Andy Kirkpatrick.)