Let's talk about off-axis carabiner loading

Short attention span version: Loading your carabiner in three or even four directions is not really a concern for climbers. The carabiner can take a higher load than you will ever put on it in a realistic recreational climbing scenario.

Carabiner rating overview: To attain the CE (“Conformité Européene”) safety rating, carabiners are tested in three loading configurations: along the spine (major axis), gate open, and minor axis (aka, cross loaded). These values should be visible on every carabiner, and surely you’ve noticed them.

The optimal load for a carabiner is along the major axis, or spine. This number should always be the highest of the three ratings, which tells you that’s the strongest configuration. Hopefully you learned this on your first day of climbing, because it's pretty important.

image: https://www.blackdiamondequipment.com/en_US/qc-lab-off-axis-tri-axial-carabiner-loading.html

However, in many real world climbing situations, carabiners are loaded in something other than these three tested configurations. Let’s look at a few.

One of these is the weakest configuration, “nose hooking”. A nose hooked carabiner can break at a load as low as 2 kN, yikes! (Here's an entire article from the Black Diamond Quality Control lab about nose hooking.)

A nose hooked carabiner, yikes! This is super dangerous, if you ever see it, stop and fix this right away!

There are other ways carabiners can be loaded, which is from three or four different directions. Our engineering friends call this “tri-axial” or “quad-axial” loading.

Note, there’s no official strength rating for carabiners under these multi directional loads. (Probably because there are too many variations and it would be hard to test consistently? I don't know, that's a guess.)

What about these examples of tri-axial loading? Is this really something to be concerned about, or not? Most people would say yes, because when you see the Petzl “Yer Gonna Die - YDG” icon, that should get your attention!

But okay, you might be saying, these examples below are kind of silly, most climbers know you shouldn’t load a carabiner like that . . .

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Examples-of-dangerous-carabiner-loading-?ActivityName=Rock-climbing

And, from this page of the excellent Petzl website, comes this interesting graphic.

Now, depending on your anchor building style, this might be something you see more often. Petzl says don't do it, but what are the real world values we're talking about?

(Let's not freak out about that 7 kN value. Petzl is talking about directly cross loading the gate, which we all know is bad, but still something to keep in mind.)

Good thing the clever engineering gnomes at Black Diamond had the same question and decided to break some gear to find some answers. The premise: When a carabiner is loaded in three (or more) different directions, it’s weaker. The question is, by how much, and is it enough to worry about?

We have some real data and testing results below, but let's first look at a real world anchor.

Let's have a look at this anchor below made by IFMGA Certified Guide Karsten Delap. The top “master point” carabiner is clipped through both of the rappel rings. (Some folks get concerned doing this might damage the rings. It actually won't, because the rings are steel and the carabiner is made of softer aluminum. It's like using a plastic ice scraper on your car windshield. The soft plastic doesn't hurt the harder glass.)

image: IFMGA Guide Karsten Delap - https://www.instagram.com/p/B5EjrGojxdI/

This is “quad-axis” loading, as the carabiner could receive a load in four different directions. Problem, or not?

No problem. Realistically, loads in this configuration are going to be low. It's the hanging weight of the belayer on the clove hitch, say 1 kN, and belaying your second up directly from the anchor, a max load of say 2-3 kN. (Also note that the second is being belayed on the right, or spine side of the anchor carabiner, which is the strongest orientation.) Once the second is at the anchor, and the new leader heads out, the new belayer will probably only have a clove hitch on the master carabiner.

As we see in this nice diagram below from Petzl, when you do clip two different loads to the same carabiner, it's best to clip the heaviest one closest to the spine.

So, once again the forces in the real world are going to be significantly less and in a different orientation than in the laboratory.

But, breaking gear is fun, so let's see what Black Diamond has to say!

Here’s the original article from the Black Diamond QC lab archives. (Keep in mind that this testing was done on a very small sample size, on one model of carabiner, from one manufacturer, so the results do not apply universally.)

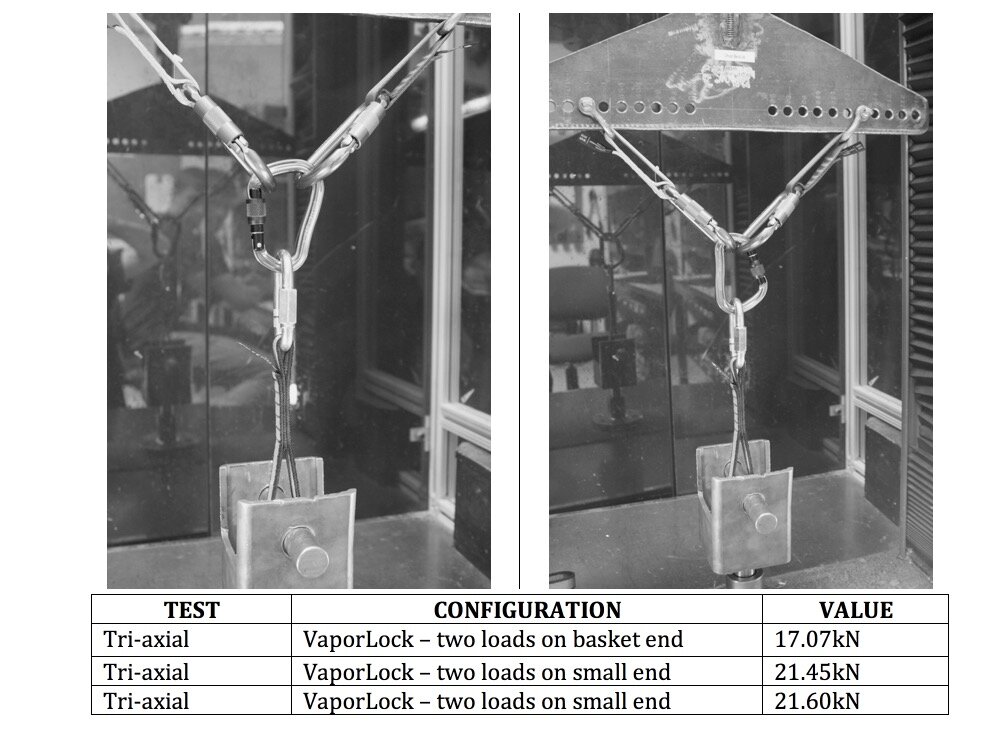

The Black Diamond website tells us that the Vapor Lock screw gate carabiner has a major axis, closed gate strength of 21 kN. Below are photos and test results from some tri-axial and quad-axial loading done by Black Diamond.

(If you're on a mountain rescue team or doing industrial rigging, or need to maintain your 10:1 safety factor, then you're probably using things like rigging plates to attach multiple carabiners to one anchor and not doing three or four axis loading in the first place.)

image: https://www.blackdiamondequipment.com/en_US/qc-lab-off-axis-tri-axial-carabiner-loading.html

Summary of tri-axial loading test: With two loads on the widest end, the carabiner was weakened approximately 20%. With two loads on the small end, the carabiner was effectively not weakened at all (Remember, the carabiner is rated to 21 kN.)

image: http://www.blackdiamondequipment.com/en_US/qc-lab-off-axis-tri-axial-carabiner-loading.html

Summary of quad-axial loading test: With the carabiner locked, the weakest iteration of the test showed about a 25% reduction in strength. Even so, this was still almost 16 kN, which is sufficiently strong enough for just about any climbing application. (Look at the loading angle onto the top of the carabiner in that top left photo, that is pretty extreme!)

Here's a great video from our friends at How not to Highline. The video is on three-way loading in general. They test various configurations of quickdraws pulling at different angles, and different shapes of carabiners. In one example, and oval carabiner clipped with two quickdraws at about a 90 degree angle broke at around 21 kN.

A tiny CAMP Nano carabiner, one of the smallest made, broke at around 17 kN with the double pull on the narrow end, and about 11 kN with the pull on the wide end. (Screen grab below of the set up.)

So, it appears it if you are going to triload a carabiner, having the double directional pull on the skinny / hinge side of the carabiner gives increased strength.

Here's another test, from Over the Edge Rescue in New Zealand. The carabiner is a CT Snappy screwgate, rated at 23 kN on the major axis.

Three-way loading, wide gate down, three different tests. Average breaking strength: 23.7 kN.

That’s higher than the rated strength!

image: https://overtheedgerescue.com/canyoning/vlad-master-carabiner/

And, here's a 30 second video from Australian rigging expert Rich Delaney at Ropelab: “Three-way loading, no problem.”

Takeaway:

Always try to load a carabiner along the spine (the strongest orientation) whenever possible.

Quad-axial loading can reduce carabiner strength by a maximum about 25%, to about 16 kN. Other configurations of tri-axial loading show essentially no reduction in carabiner strength.

In all cases, this is considerably stronger than 9 kN, which is about the maximum force possible in climbing.

So, in those oddball situations where optimal carabiner loading is not possible, it's probably going to be fine. Just don't make a habit of it. =^)

So, that’s some lab break test results, admittedly on a fairly small sample size. Alpinesavvy does not give advice, we offer ideas and information.

I'm not here to tell you what you should or should not do when to comes to building anchors. Look at these results and decide for yourself.

What do you think?