The "extended" rappel

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

This article was written with collaboration from Sean Isaac. Sean is an ACMG (Association of Canadian Mountain Guides) Certified Guide, a former professional climber, and author of the “Ice Leader Field Handbook” and “How to Ice Climb” (2nd ed.) Follow @seanisaacguiding for tech tips. Thanks, Sean!

Here are articles on two closely related techniques that use rope blocks:

Your rope is too short, what do you do?!

You’re rappelling from a multi-pitch rock climb with a single 60 meter rope. All pitches on the way up were less than 30 meters except one that was 35 meters long. (You know this because your attentive belayer noticed the middle mark going through the device before the leader arrived at the next anchor. Another great reason to have a middle mark!)

Whoops, should've read the guidebook and brought the 70 m instead of the 60 m, but here you are.

How do you rappel and still pull your rope? (This is an unexpected situation, so you don’t have a pull cord/tag line, nor a clever tool like the Beal Escaper.)

Answer: the extended rappel.

Hopefully you don't find yourself doing this very often, but if it occasionally happens, this #CraftyRopeTrick could save the day. There are several variations on how to set this up. Here’s one.

Short version:

Instead of doing a standard rappel on both strands of the rope, you secure one strand to the anchor and make sure it’s absolutely long enough (here, 35 meters) to reach to the next anchor or to the ground.

Tie a rope block (knot or carabiner) on the short strand.

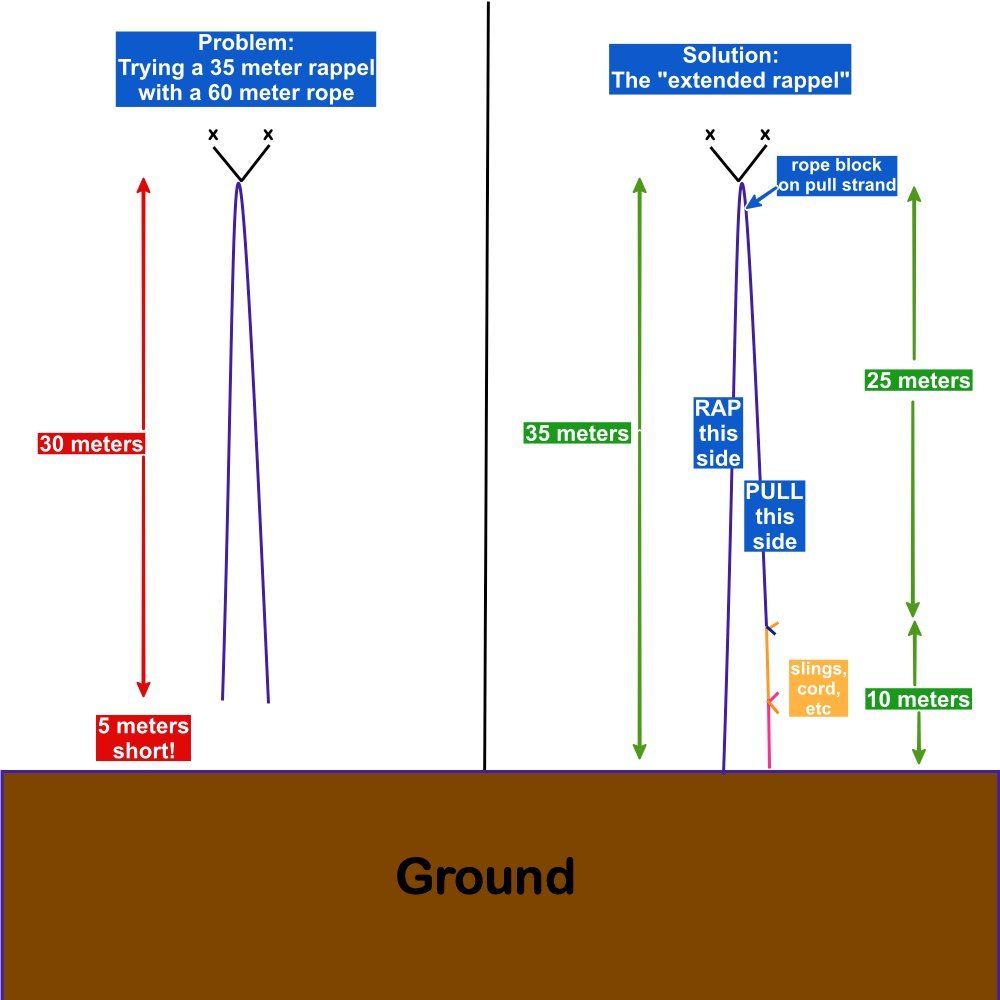

The long strand of the rope, which is 35 meters, reaches the lower anchor. The short strand of the rope (the pull side) is 25 meters long, and is hanging 10 meters above the lower anchor. Can you visualize this? Good!

The first person rappels single strand on the long side to the lower anchor.

The last person rappels single strand on the long strand, ideally on a Grigri so they can go hands free. They keep control of the short strand by clipping it to a quick draw on their harness.

When the last person reaches the end of the short strand, they start adding material (cordelettes, slings, etc.) to extend it. (“Extended” rappel, get it?)

Last person continues rappelling to the anchor. Retrieve by pulling the short side with your “extension” tied to it.

It's a tricky to take a decent photo of the rigging, so hopefully this diagram can help.

Conceptually this may sound pretty easy. In practice there are a lot of considerations to doing this efficiently and with the least risk.

The primary safety concern is making a block in the rope that absolutely positively cannot pull through the anchor hardware. The best anchor hardware for doing a rope block is small chain links, or small to medium sized quick links. With this type of hardware it is pretty much impossible for the blocking knot to pull through. Keep reading for more discussion of rope blocks, and here's a longer article about them.

Here's a more detailed explanation of each important step.

When might you need to do an extended rappel?

The route was bolted for a 70 meter rope, and you brought a 60.

It's a climb you've never rappelled before and have no beta.

Maybe the beta is wrong.

Maybe the beta is correct if you use THAT anchor.

Maybe the anchor that people used to rap from is gone or was moved.

More extreme situation: Your rope got damaged near the end, you had to cut off some of it and now your rope is too short to make the standard rappel stations.

What's a big potential problem with the extended rappel?

If you begin to pull your rope, the end of the “real” rope goes up out of reach, and then the rope gets stuck. You’re now holding onto your “extension” as the only way to fix the problem. If you're on the ground, you can walk away and hopefully go get another rope and deal with it. If you are way off the deck on a multi pitch rappel, you could be in a serious situation.

What’s another option to descend?

The simplest and maybe least risky way to descend, if you have access to another rope and you're within one rope length of the ground: Tie off one end of the rope, toss it and be sure it reaches the ground, rappel, and come back and get it later with another rope. Plus, if you don't have enough extra slings/cord to extend the short side of the rope, then this approach is pretty much mandatory. Yes, it's a hassle and would kind of suck, but certainly better than the alternative.

What if you don't notice your rope is too short at the top, but only after you find yourself dangling on both strands, short of the anchor?

Yikes, scary! That definitely complicates things. There's no simple universal solution to this that I know about. You're probably gonna have to get resourceful - put some pro in a crack and build a temporary anchor, or clip into a bolt. Good reason for the first person down to carry some gear to do this.

What's the ideal terrain to try an extended rappel?

Best if the rock face is smooth, clean, and vertical with minimal chances of your rope hanging up.

Setting the correct rope length

There are a couple of ways to do this. 1) Lower the first climber 35 meters to the next anchor, or 2) Fix one strand from the end, have them rap on this, tie off the bottom end of the rope and then pull up the rope from above to set the correct length.

If you don't know the distance of the next rappel, you can lower your partner and keep an eye on the middle mark of the rope. If the middle mark passes through your anchor before your partner reaches the lower station, then your rope is too short.

If you’re lowering your partner, follow standard safety procedures such as closing the system by tying a knot in the end of the rope (assuming it's not tied to you) and use a third hand / autoblock backup.

If you lowered the first person down, they can stay tied in to the end of the rope to be sure that the last person does not rap off the end, and that one end of the rope is for sure at the lower anchor.

Extending the pull side

Before the first person heads down, they hand off all of their extra slings, cordelettes, etc. to the last climber. If both climbers have one cordelette of about 5 meters, there’s your 10 meter extension. This strand of the rope is not load bearing, you're only using it to pull down the long strand.

To connect slings to one another, girth hitch them together, no carabiner required. To connect a cordelette to the end of the short strand of rope, you can use a flat overhand bend. (This is another good reason to carry an “open” or untied cordelette, rather than one that's tied into a loop with a permanently welded double fisherman's knot.)

Rather than monkey around with extending multiple slings while you’re hanging in space, it's probably less risky and easier to connect all the slings you plan on using up at the top anchor before you start rappelling.

The extended rappel relies on a rope block. While conceptually simple, there are lots of factors to consider.

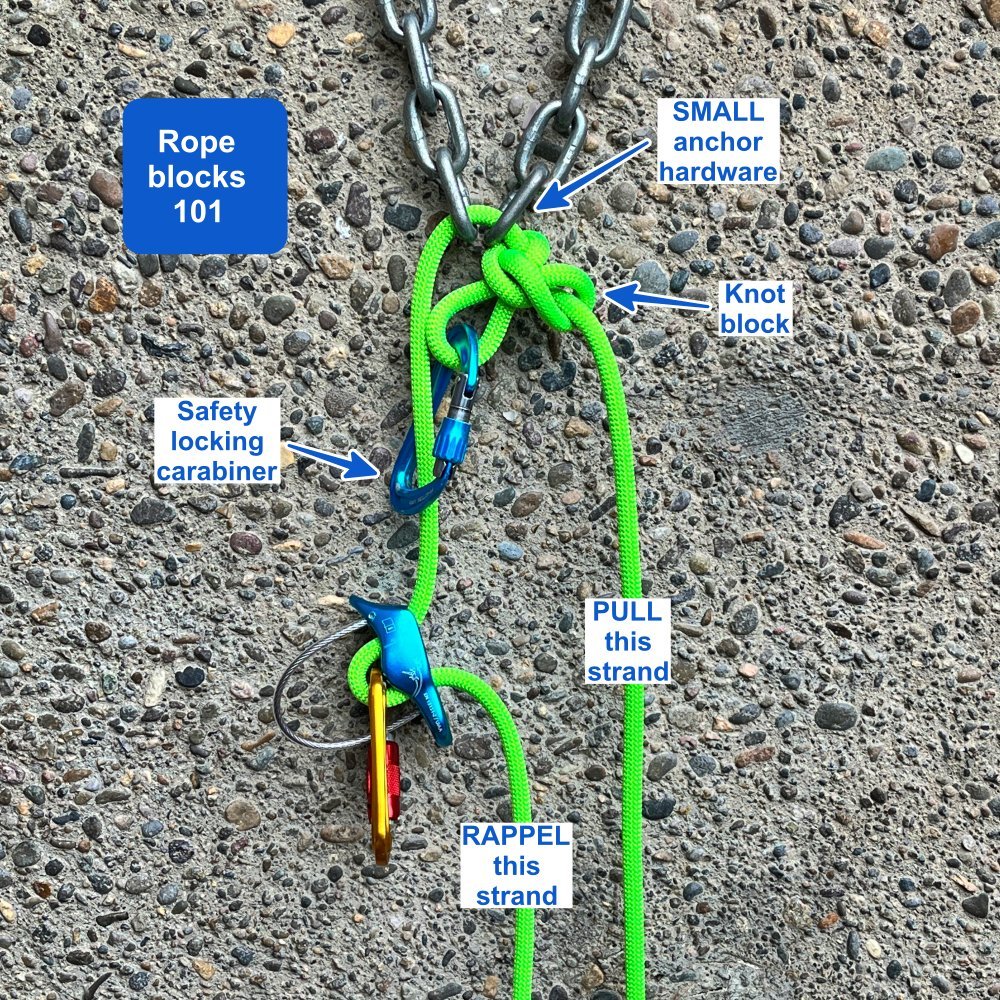

Detailed look at one way to set up a rope block.

The rope block

This extended rappel technique requires the skill and knowledge to use what's called a rope block. This goes by various names: knot block, carabiner block, static block, Reepschnur. This creates an obstruction on one strand of your rappel rope, that cannot be pulled through the anchor master point. The rope can slide freely in ONE direction, but not in the other.

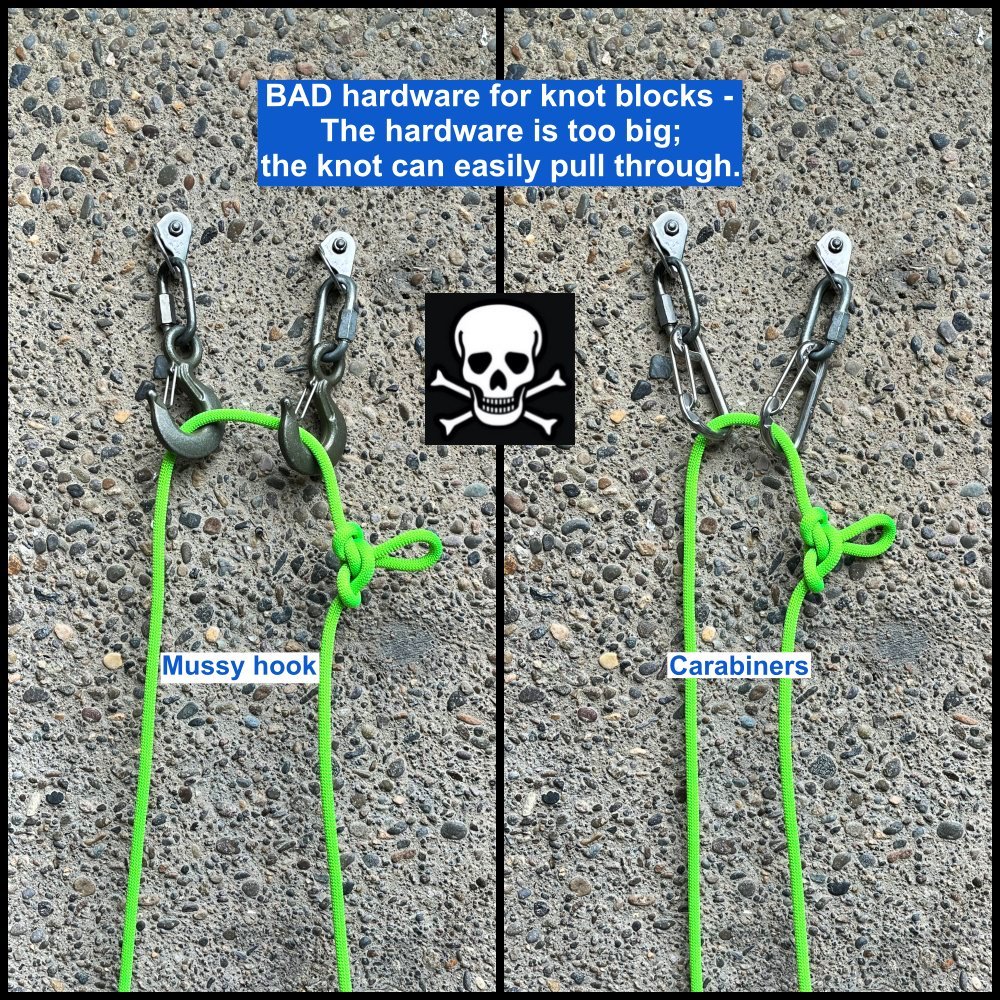

The golden rule of the rope block is that the block absolutely cannot pull through the master point on the anchor. If it does, the person rappelling will probably die or your rope will get hopelessly stuck.

Typically a knot block is tied with butterfly or a figure eight on a bight. If you need a larger block, you can tie a well-dressed clove hitch around the spine of a locking carabiner, that works also.

This is an advanced technique, popular in the canyoneering world. Like many other things in climbing, if you screw it up you can die, so pay attention and absolutely practice on safe flat ground before you ever do this in the real world!!

Anchor hardware concerns

This usually requires that the anchor master point is quite small, such as a chain link, quicklink, or a small bight knot tied in cord or webbing.

If you're rappelling through a carabiner or a large ring, the opening may be so large that a block may not work.

This is an excellent time to use a quick link on the master point, if you happen to have one.

Below: knot block on large diameter anchor hardware, don’t do this!