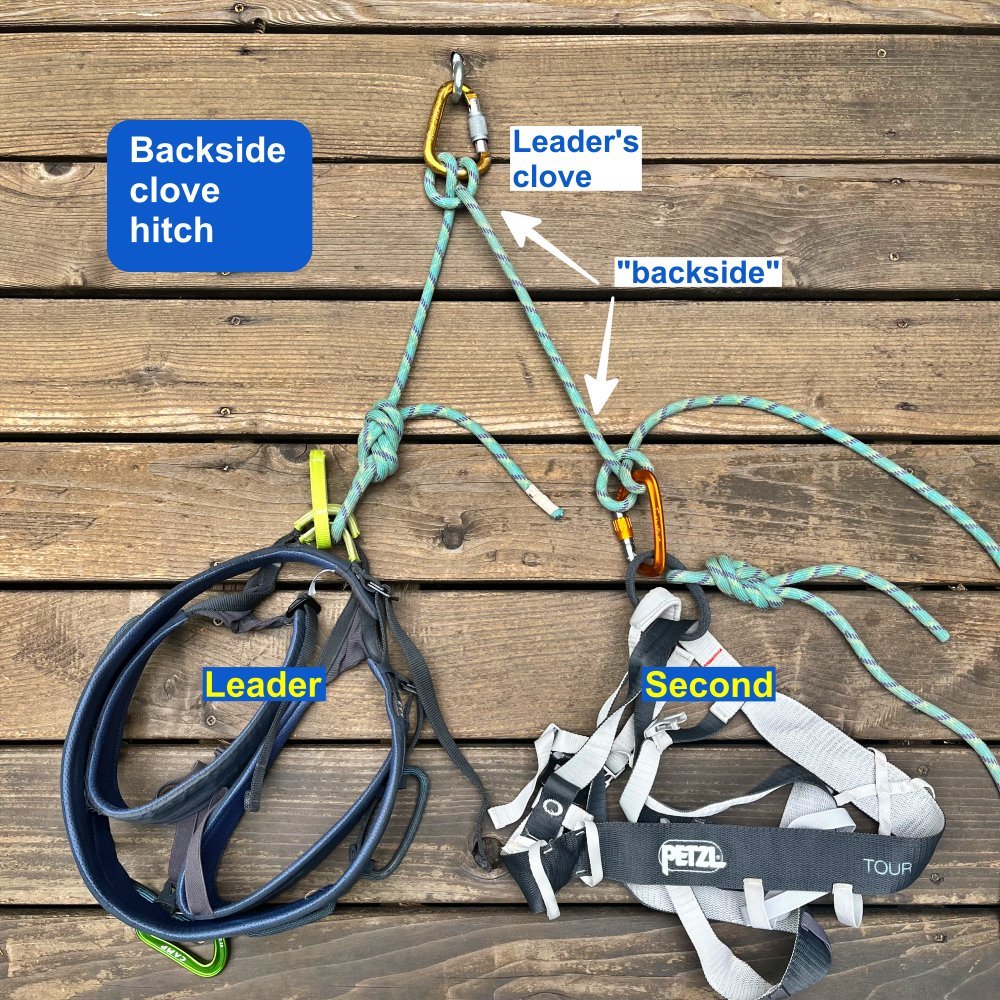

Backside clove hitch: transition to rappel

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

Using the backside of the leader’s clove hitch is a great way to transition from climbing to descending.

Advocated by IFMGA Guides Marc Chavin and Rob Coppolillo (authors of the excellent book “The Mountain Guide Manual”) this method uses the climbing rope coming off of the leader’s connection to the anchor as the primary anchor point for the follower, as opposed to the second clipping a tether to the anchor master point.

Lots of multi pitch routes require a rappel to get down. For many climbing teams, this transition period, from moving upwards to moving downwards, can be a bit of a cluster.

The traditional method is each climber using a tether/PAS to connect in close to the anchor, each person untying from their respective ends of the rope, threading the anchor and then each person rigging for a rappel separately. This can be awkward at tight stances, and often takes a LOT longer than necessary, especially with less experienced folks.

The backside clove hitch elegantly address some of these issues.

(Another term I've heard for this method is the “Backside Rappel Feed”, or BARF. I love it, but it hasn't caught on yet.)

It can take a bit of creative visualization to try to imagine how this works in your head. I have to say it took me a while before I got it figured out. But once I did, and realized the subtle benefits that come from this system, I knew it was going to become a regular part of my rappel routine.

I strongly suggest you try it on flat ground with a partner a couple of times to get the hang of it, and watch the video at the bottom of this page!

What are some benefits of the backside clove hitch?

1 - Cluster free anchor. By having the follower clipped to the backside of the leader’s rope, there’s no need for multiple leashes clustering up the anchor. You have plenty of room to stretch out and move around a bit, assuming the ledge allows you to do so. Your position isn’t limited by a short tether or PAS.

2 - Always using the dynamic rope to connect everyone to the anchor. Ropes are stretchy. Generally, tethers and slings, not so much. Stretchy is good. Use it when you can.

3 - (Close to) zero chance of dropping the rope. For a two person team to transfer to a rappel, of course one end of the rope needs to be freed up to pass through the anchor. With the backside clove hitch, this is simple: because the leader’s end of the rope is securing the entire team to the anchor, the follower’s end of the rope will always be the one threaded through the anchor. The leader remains tied to their end during the whole process. Rule number one in setting up a rappel is don’t drop the rope, and this method pretty much ensures that can never happen.

4 - Faster and less risky rappelling. After the follower threads their end of the rope and and pulls to the middle point, both climbers can rig for rappel. A low risk and fast way to do this is to rig an extended rappel with both climbers doing so at the same time. The extended rappel means climbers can check each other, which reduces risk. Because they both rig for rappel at the same time, and also increases speed, because the second can begin their rap the moment the first person is at the next anchor.

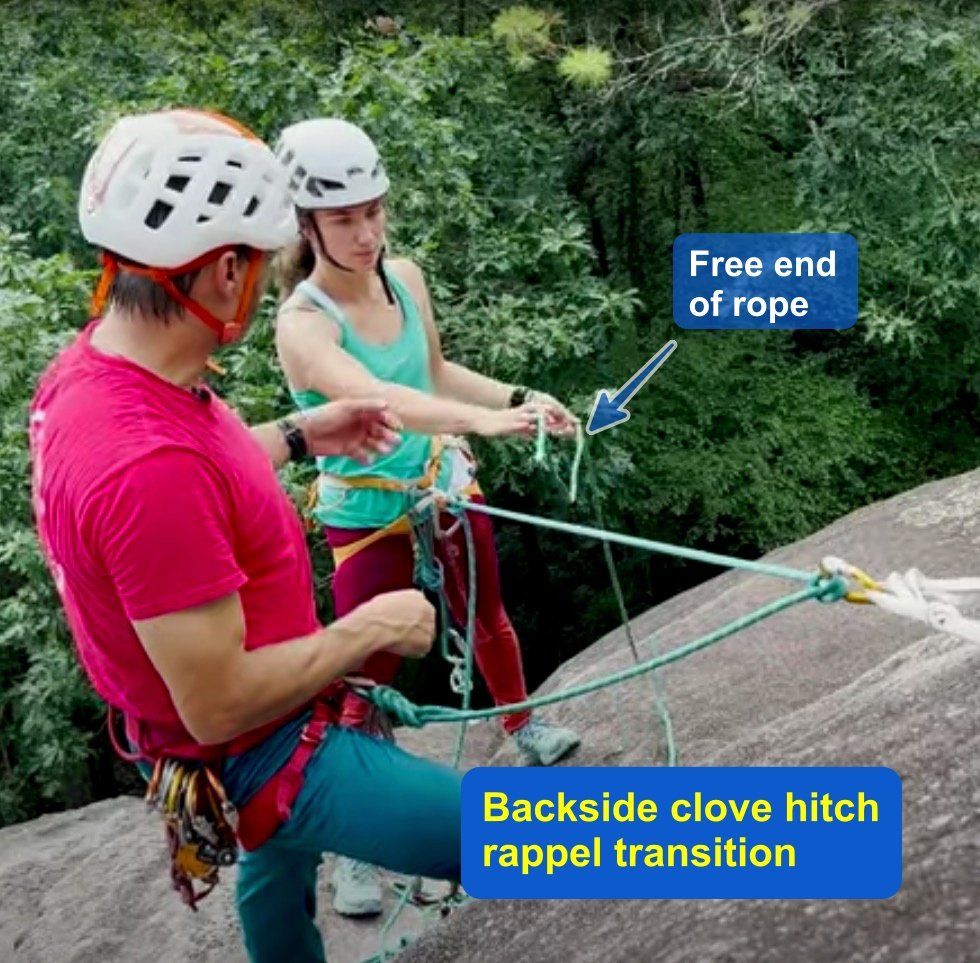

Here’s the general procedure:

When the leader is securely attached to the master point with the clove hitch, they tie a clove hitch or a loop knot (overhand, fig 8, butterfly, your choice) on the backside of their clove hitch connection. This hitch/knot gets a locking carabiner.

The second arrives at the anchor, and clips this locker to their belay loop.

The leader takes the follower off belay, and removes the belay device from the anchor.

The second unties, freeing up a rope end.

The team threads the rope end through the anchor, pulls it to the middle point, and tosses that strand.

Both climbers rig an extended rappel and a third hand backup.

Both climbers are now secured by their extended rappel. The second removes the hitch/loop knot and carabiner from the backside of the leader’s clove hitch. The leader unties, tosses down the second strand of rope, and cleans the anchor.

Do a safety check, and rappel.

In the video below, the second climber rappels first. However, there can be some advantages for the leader descending first. Here, the leader remains tied in the entire time, the second rigs their extended rappel above the leader. Doing this has a few extra benefits:

The leader can’t rappel off the end of the rope, because they are tied to one strand and it's blocked from above by the second.

It's a bit less rope management, because you only have to throw one strand instead of two.

You only have to tie a stopper knot in the one strand that you're throwing.

Whether you choose this method can depend on factors like the stance, team experience, and single pitch or multi pitch.

image: screen grab from https://youtu.be/feuVDCnS4g0

So, that's about it, It’s a fairly simple concept, that can make your transitions faster, smoother and safer. But it may require a big re-think of the way you're probably doing things, so absolutely practice in a controlled environment and see if it works for you.

As with most climbing techniques, it's a better show than a tell. Check out the video below from IFMGA Guide Karsten Delap showing the entire process.

In the video, Karsten also shares another clever use for the backside clove hitch method: removing twists from the rope.

If, for whatever reason, when the second arrives at the anchor there are twists in the rope, the second can temporarily clip to the backside of the leader’s clove as described above, untie from their end of the rope, remove the twists, and tie in again.