Alpine Tips

The quad anchor

The quad anchor rig offers fast set up, great strength, good load distribution and complete redundancy, all in a light, compact package. Learn all about it here.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

The quad anchor, first mentioned (I think) around 2006 by John Long in his book “Climbing Anchors”, was an attempt to have the Holy Grail in anchors. What’s cool about the quad?

Good load distribution

Minimal extension

Fully redundant

Quick to set up and break down, no knots to untie

Super strong (would you believe 40 kN?!)

Bonus, two independent and load distributed master points, which can be quite handy

Well, it didn’t catch on right away. One reason may have been that the original version suggested using a long and bulky cordelette to rig it.

Traditional quad anchor rigged with 7mm cordelette. Nothing really wrong with it, just big and bulky.

Well, here’s the modern iteration of that idea, in a much lighter and more compact package. Rather than using a huge honker cordelette, instead you use a Dyneema sling; I prefer 180 cm. Double it, tie two a figure 8 or overhand knots (with the stitching in one of the end loops), and then use two strands to make an anchor for both toproping and multipitch.

The knots stay in the sling for at least the entire day. It's good practice to untie the knots every few days or after a weekend of climbing to “rest” your sling.

This system works best with two solid pieces of gear that are fairly close together and ideally in a horizontal plane. Two bolts on a sport route are a perfect application. Two ice screws that are slightly offset would also work too. (If you’re building a 3 piece anchor from trad gear, it may be faster to use a more traditional cordelette.)

What's the best sling length?

For me, the 120 cm is a bit too short. It can work if the bolts are very close together and you use a small diameter sling, like 8 mm.

I think 180 cm is about the sweet spot. Not too short, not too long, works on horizontal bolts and with a little adjusting, vertically offset ice screws.

Some people think this is called the quad anchor because it uses a “quad” length sling, or 240 cm. A 240 cm sling can be handy for many kinds of anchor building, especially for equalizing three points of protection, orslinging around a tree. But for side by side bolts like this, many people find it’s too long, a bit bulky, and hard to rack.

But hey, as you can see below it's only a bit longer than the 180, so many people this is gonna work fine.

Notice the 180 and the 240 are tied with a figure 8 rather than overhands. This uses up a bit more material which raises the master point, and it also makes the knot quite a bit easier to untie after it's been loaded.

Here's another trick with the 240 cm sling quad to make it a little more manageable. Instead of doubling the cord, you can triple it. Then, when you tie your knots, it raises the master point and you clip to three strands rather than two. This makes it the effective same size as the 180 cm sling, nice!

If you look carefully at the photo below, you can see the yellow locking carabiner is clipped to three strands of cord, rather than two.

If you were climbing a route that maybe had a mix of gear anchors and bolt anchors, this might be a good trick to be able to use the 240 for both.

Quad toprope anchor

Lockers on each of the two bolts, opposite and opposed lockers for the rope, good to go.

There's some difference of opinion about whether you should clip the master point lockers onto two separate strands (left), or put both of them onto three strands (right).

Argument against the set up on the left: the sling arms could rub against each other when loaded, and the carabiners might bind against each other a bit, giving you less than ideal equalization.

Argument against the set up on the right: if either bolt where to fail, you're only being held by one additional strand.

I think both of these issues are highly unlikely, and you're gonna be fine no matter how you rig it. Personally I prefer the one on the left.

(Hopefully this is glaringly obvious, but you absolutely should NOT clip all four strands. If you did this and any anchor point failed, the carabiners with slide off and you would die.)

Side note regarding lockers on the bolts . . . For a top rope anchor, when you're not right there next to it to keep an eye on it, and maybe multiple people will be using it over a long period of time, it's good practice to use locking carabiners on the bolts. In some circles this is known as an “unattended” anchor. However, if you’re multi pitch climbing, it's fine to use non-locking carabiners on the bolts. We can call this an “attended” anchor, because there's someone there the whole time watching it.

Notes . . .

For those of you who are extra concerned about tying a knot in Dyneema . . . A full strength Dyneema runner is about 22 kN. Here, we are doubling the sling, which in theory makes it about 44 kN, and then we're tying a knot, which reduces that in about half, which brings it back down to about 22 kN. In other words, it's absolutely not an issue. We cover the “tying a knot in Dyneema” issue more detail here.

A 180 cm sling can be a bit hard to find, But is this type of anchor becomes more popular, hopefully more manufacturers will offer them. (If the links below don't work, just Google around until you find them.)

A skinny Dyneema sling is best for this. (It won’t work nearly so well with a nylon runner because the knots are too big, plus finding a 180 cm nylon runner is difficult.)

A 10 mm or 11 mm Dyneema sling is recommended for anchor building. These are larger than the 8 mm used in many 60cm and 120cm slings. Most of the 180 cm slings I have seen are in this larger diameter, so that's good.

How strong is the quad?

Ridiculously strong. How about a 40kN break test? The great team at HowNot2 tested this several times, and the quad is WAY stronger than anything else you will probably have on your harness. See the video here.

image: screen grab from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=she8vH1DCBU

Can I clip the shelf? Yes. HowNot2 did a pull test on the shelf, and the knot started sliding at around 13 kN. SuperGoodEnough! (Same video link, start at 7:00.)

Quad with a cordelette

While I'm generally not a fan of the 7 mm cordelette, you can certainly use one to make a quad anchor. In the photo below, the red cord is Sterling Powercord. While it’s a bit expensive, it's only 6 mm but is rated to 20 kN, almost 3 times stronger than normal 6 mm cord. If I am carrying a cordelette, this is what I grab first.

As the saying goes: “You can have it strong, light, and cheap. Pick two.”

In the photo, both left and right anchors are structurally strong. However, the right photo, showing the knots tied a bit lower, is slightly preferable. In the highly unlikely event of a bolt failing, the lower knots limit the extension of the anchor.

Here's another option: Tie a “figure 9” knot rather than an overhand knot to isolate the strands. This is simply a figure 8 knot with one more turn. This has a few advantages: it brings your master point up a bit higher, because the knot takes up more cord, and because of the extra turns, it's easier to untie at the end of the day.

Want to learn more tips about the quad anchor?

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

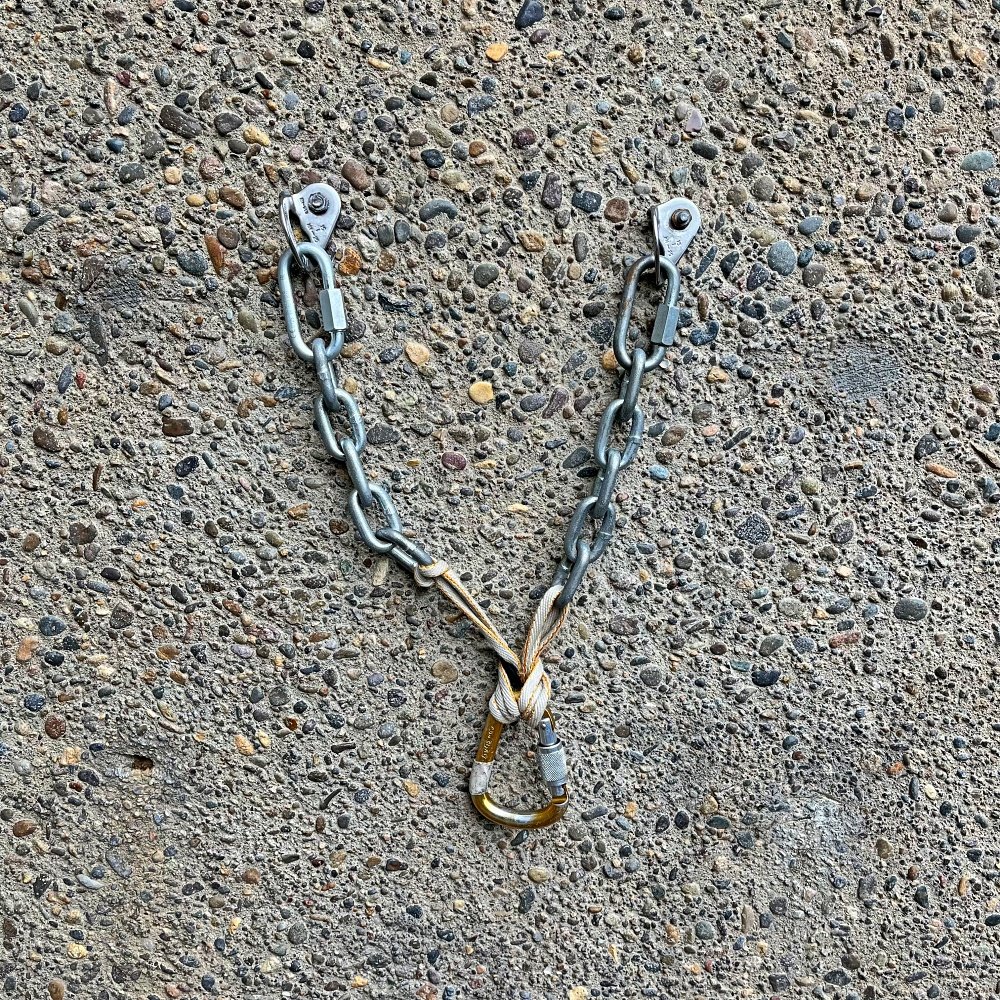

Clip a chain anchor directly with a master carabiner

Find yourself at a chain anchor with a single huge ring or two equal lengths of chain? Lucky you, your anchor building may have gotten a lot easier. You can probably clip the bottom chain links with a large HMS carabiner and simply use that as your master point.

You're on a multi pitch route. If you come across a stout chain anchor, and if the bolts are close together and/or the chain is quite long, lucky you! You’ve got about the easiest and fastest anchor you could ever build. (Note, a vertically oriented chain anchor is also perfect for this, we're going to cover that in a new article soon.)

Why is this a sweet setup? Extremely fast to build, minimal extra gear, no slings, no knots, really easy to break down for your second.

Get the largest HMS “pearabiner” belay carabiner you have, clip the bottom two links, lock it, done. That becomes your “master carabiner”.

Note: Carabiners are strongest when loaded along the spine. When you bring up your second, that will be a larger load than just holding your body weight. So, take a moment before you clip that master point carabiner to have a look at where the rope is running down the pitch. In this example, let's say the rope is coming up from the left side of the anchor. Ideally, that means the spine of the carabiner would be on the left to take the potentially larger load, and the gate of the carabiner should face to the right.

Check out the nice diagram from Petzl to see how this works. In the diagram, the loaded rope is closest to the gate, the weakest configuration. In theory, It would be better if the load strand were on the left, closest to the spine.

(In my humble opinion, this is more of a potential issue with large loads. When bringing up your second, the load is never going to exceed 2-3 kN, so it's probably not critical if you forget to do this step. But it’s best practice, so it’s worth mentioning.)

image: Petzl.com

Add a smaller locking carabiner and clove hitch to the master point to secure yourself.

Clip your plaquette style belay device and blocking carabiner to the master carabiner. (As mentioned above, ideally clip this closest to the carabiner spine, because that's going to be taking a slightly higher load than just your bodyweight on the right.)

Finally, if you’re feeling courteous and have a spare locking carabiner, you can clip that to the master point on the far left to give your second a convenient place to clove hitch themselves when they arrive.

Possible concerns, addressed. (In some climbing situations these are valid concerns, but not necessarily here.)

Clipping multiple carabiners together!

Clipping directly into the rappel rings and possibly damaging them!

Loading the carabiner in multiple directions!

Clipping multiple non-locking carabiners together and having them flop around is a bad idea, because they can unclip themselves. However, at an anchor like this, when you use all lockers and there is no flopping movement of the carabiners, this is acceptable practice. We cover this more in this article.

Clipping into the rappel rings is totally fine with aluminum carabiners. Aluminum, being softer than the steel ring, is never going to damage the rappel hardware. (It's like using a plastic ice scraper on a car windshield; the soft plastic is never going to hurt the glass no matter how hard you scrape.) We cover this in detail here.

Loading a carabiner and three or four directions at once (known as tri-axial and quad-axial loading) can weaken a carabiner. But in this case it's not a worry, because the chains are quite long and the loads are not going to exceed 2 or 3 kN. If the loads were higher, and chains were shorter and/or the bolts farther apart, it might be a concern. Multi axis carabiner loading is an interesting and slightly complicated situation, and we cover it extensively in this article.

Detour to a toprope anchor: If you’re rigging a top rope on a chain anchor, and maybe you're short on quickdraws or other anchor material, you can clip two carabiners opposite and opposed to the bottom links. Ideally one of these is a locking carabiner.

This is generally not standard practice, it's usually a better option to use two quick draws or a mini quad, but if you're short on gear this is acceptable.

Note: if you do this on a link of the chain, you'll probably have enough room to pass the end of the rope through but probably not enough room for a bight of rope to lower from. In this case, there are large quick links at the bottom, so there's plenty of room to rig for lowering off, as shown in this article.

(I first saw this technique in a YouTube video (at 7:45) made by AGMA Rock Guide Cody Bradford.)

Here’s a nice video from Outdoor Research that shows many of these concepts in action. Important points mentioned in the video:

Avoid using smaller D shaped locking carabiners at the master point, because the carabiners become stacked on one another and the loading becomes less than ideal.

Of course, always avoid directly cross loading any carabiner gate; that’s a bad thing.

If the bolts are too far apart, and/or the chains too short, you might start to get some side loading on the top part of your carabiner. Be mindful of this, and re-rig with a sling if you don't like it. Here's an article on strength reduction from off-axis carabiner loading. (It's probably a lot stronger than you think; you'll be fine.)

Thoughts on redundancy in climbing anchors

Redundancy is one of the tenets of anchor building, for good reason. It's a great rule for most climbers in most situations. But, it’s actually more of a situational and subjective guideline than a black and white rule. Learn some of the factors that may influence this choice, and see some examples of non-redundant anchors in action.

This article was written with editorial assistance from Richard Goldstone, thanks Richard!

Redundancy in anchors, while a good maxim for most climbers in most cases, is a situational and not an absolute rule.

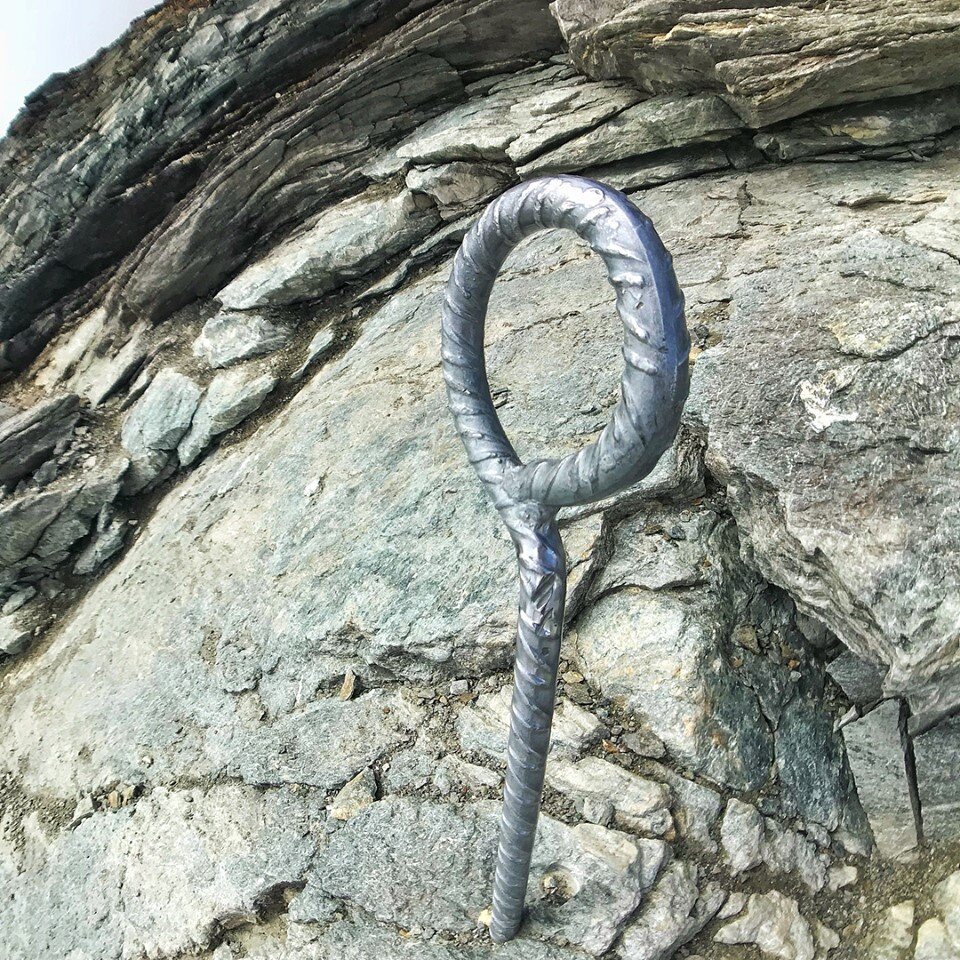

One of many single piece, non redundant anchors on the Matterhorn. Photo by Dale Remsberg.

Single point, non redundant anchor on the matterhorn. photo: Dale Remsberg

“Good judgment comes from experience. Experience often comes from surviving bad judgment.”

Will Rogers

One of the core concepts of anchor building is redundancy - if any single component were to fail, the entire anchor wouldn’t fail. This mandate has been around for a long time for a good reason, because it's arguably the single best thing relatively newer climbers can do as a buffer against the mistakes of inexperience. The sketchier the situation, the more redundancy counts. When in doubt, double up isn’t a bad rule to live by. If you have the gear and the time, do it.

Sliding X anchor? Not redundant. If that sling gets cut, adios.

Statically equalized cordelette style anchor? Perfectly redundant, if any part of the sling fails, the rest of the anchor still works.

However, outside of anchor construction, climbing has many mission critical components that are not redundant.

Most of us climb on one rope

Pretty much every harness has one belay loop (Yes, it's doubled over and sewn, but it's still one piece of webbing)

We belay and rappel with one carabiner, with one belay device

We clip the one bolt/hanger with one carabiner/draw as the first clip on a sport route, and would deck if it fails

You get the idea. Why do we accept so many potential “single points of failure” in many parts of the system, yet demand it always be a component of our anchors?

The answer is, it doesn’t always have to be. Rather than being a mandate for every anchor, all the time, think of redundancy as a concept that applies in varying degrees to varying situations. It’s overall a good idea, and you should never be faulted for doing it, but it’s a situational, and not absolute, rule.

IFMGA Guide Dale Remsburg writes: “The idea of redundancy comes from pieces in the rock, not the links or tools we use to connect them.”

Keep in mind, creating redundancy comes at a cost of time, or gear, or both. Mostly, that’s a good tradeoff to make. Other times, perhaps not.

A fundamental principle of economics (and many other aspects of life, including anchors) is the law of diminishing returns, which, in econ-speak, means that adding additional factors of production eventually results in smaller increases in output. Say that it takes one builder one year to build a house. So, if you have 365 builders, can you build a house in one day? Of course not, because after a certain point, the extra production (builders) result in lower output (less work getting done because they are tripping over each other).

And yes, this can apply to building anchors. Continuing to add “production” (additional slings, backups, double locking carabiners, etc.) at some point do not significantly increase your “output” (safety margin), so it's probably not so smart to keep doing it. Of course, the question becomes, where do you cross that point? There's no firm answer, but here's one way to think about it mathematically.

Say that the odds of failure of an anchor sling are one in 1,000. If you backup that sling with another, the theoretical odds of anchor failure become 1,000 x 1,000, or one in 1 million. Add a third sling? The theoretical odds of failure are 1,000 x 1,000 x 1,000, or one in 1 billion.

What's your acceptable level of risk? If you're feeling good with one in 1,000, then going to one in 1 million (let alone 1 billion) is probably not worth doing.

Another broad component of anchors is having proper context in anchor photos/examples. This gets more into the situational judgment of when redundancy is more important. It's tricky to simply show a photo of an anchor and ask if it's acceptable or not. The slightly snarky yet truthful answer is, “It depends! Some broader context questions might be:

Is the anchor for a multi pitch lead belay, top rope anchor or a rappel anchor? Loads vary a LOT between these. Peak force on a rappel anchor, 2-3 kN; theoretical max force on a lead anchor, about 9kN. (Source)

How difficult is the pitch below or above, and what’s the skill level of the climbers?

Is it a part of multi pitch climb or the top of a climb?

Is there a chance of rock or ice fall that might hit the anchor?

Is it a casual day at your local crag, or are you trying to do a remote 15 pitch alpine route?

And so on.

Let’s examine that last point - that of speed/efficiency. When people cut corners on anchor building, the usual rationale is that it saves time and/or uses less equipment. Let's be honest though, the requirements for “speed” on a relaxed three pitch climb on a sunny day at your local crag (where time, weather, and daylight are not major issues) is minimal. On a casual route with no real need to hurry, eliminating redundancy from an anchor because it saves you a few minutes is not a very compelling argument.

How about a long, committing, 15 pitch alpine mountaineering route? There, shaving off a few seconds wherever you can might become more important, because the time savings multiply over the course of a big day.

Some people always seem to be in speed mode, striving to do everything the quickest way possible. If that works for you, great. But, for most of the rest of us, and especially for newer climbers, safety should always be a priority over speed.

Let's have a look at a few anchors that question the concept of redundancy. How do you feel about them? Consider the trade-offs in time, gear or both to make the anchor “textbook” redundant.

Rappel anchor

One tree, one sling, one carabiner. Every part of this anchor is non-redundant.

However, each of these three components is vastly stronger than any possible rappel load, which at most, even with terrible rappel technique, is never going to exceed 3 kN.

The tree is well rooted and stout enough. (Some folks use “5 & alive” for tree anchors - at least 5 inches in diameter, and alive.)

Some brand new 1 inch webbing (rated about 18 kN) tied in a well-dressed water knot with good long tails. The webbing is rubbing on tree bark, not the sharp edge of a rock.

Snapgate carabiner (rated 22 kN) left behind for the rope connection, gate taped shut for extra security (aka cheapskate locker). Extra points for using pirate hockey tape.

So, whaddya think? Would you rap on it? Why or why not? If not, what would you change / add so you’d feel comfortable?

How about this anchor? It’s a Fixe PLX/Duplex anchor, standard in many parts of Europe and Canada, but not so common in many parts of the USA. Everything is stainless steel, the rings are 10 mm thick, and the whole thing is rated at 30 kN.

How about that bottom ring? The gear testing wizards at HowNot2.com tested a couple of these. One broke at around 90 kN, the other broke around 60 kN! That is miles stronger than your rope, your belay device, your belay carabiner, and all those other single points listed above. If you're happy with those single points, why not be happy with this?

This is an anchor that can leave redundancy advocates scratching their noggin. Hmm, what do I do with this mishmash of hardware? Am I supposed to clip just that ONE ring at the bottom?! That’s not redundant, if it fails, YGD! (You’re Gonna Die).

Redundancy advocates might just ignore the chains and ring, and rig this with a long runner clipped to the bolt hangers. Remember, it's probably totally fine if you choose to do this, but it’s not the intended nor most efficient way to use this style of anchor.

Here’s an Instagram video posted by AMGA Certified Rock Guide Cody Bradford using this exact style of anchor. Cody clips a single large locking carabiner to the ring making a master point, then clips two carabiners onto that, one for his clove hitch and one to belay his partner. Yep, everything off the one ring. (And then everything off of one yellow carabiner.)

Not textbook redundant, right? What do you think about this anchor set up? What would you do with anchor hardware like this if you had to belay up your partner?

Here’s another example. I first saw this anchor on the Facebook feed of Dale Remsberg, an IFMGA Certified Guide and technical director of the American Mountain Guide Association. (So yeah, Dale knows his stuff.) It's a photo he took of an anchor he built while guiding a client, and put it on Facebook to start a discussion about, guess what, redundancy. (For context, it’s on a large ledge, the pitch below is an easy 5.7ish, and there is no risk of rock fall from above.)

image: Dale Remsberg - https://www.instagram.com/p/BxH139Tj1M5/

What do you think of this?

At first glance, redundancy advocates would dismiss this immediately. A basket hitched sling has zero redundancy; if it gets cut or fails, immediate anchor failure and YGD!

Technically true, but how would this sling possibly fail? It's running around tree bark, not any sort of sharp rock. There is zero risk of rockfall from above impacting the sling. The only way it could fail for is for it to physically break, something that has pretty much never happened in the history of rock climbing outside of the ever awesome Sly Stallone movie, Cliffhanger. (Readers, please correct me on this last sentence if I’m mistaken.)

One approach to make this anchor redundant is to tie a knot in the sling. Maybe so, but what's the trade-off? You might barely have enough sling material to make the knot . . . or perhaps you wouldn't. You also weaken the sling by tying a knot. You also take the time to tie the knot, and probably a longer time to untie it, which if it gets weighted, could be a hassle. (Side note: could be a great place for a girth hitch at the master point.)

Which is more important, having the full strength of the runner, or weakening it by tying a knot which creates redundancy? Oh, and there’s just one tree branch there, that's certainly not redundant. What about that?

Now, I saved that's the best for last. Here's one that’ll give redundancy advocates nightmares. (And to be honest, I’ve never seen one of these in real life and I'm not super excited about it either . . . )

How about ONE SINGLE BOLT?!

Here’s a screen grab from a video, link below. From the video: “( . . the anchor can) . . . in some instances be a single large glue in bolt, which is the only anchor at the anchor point.”

How are you going to make this redundant? Answer is, you probably can't.

image : screen grab from: https://youtu.be/1r7hIZREJoQ?t=

Now, before you start thinking this is a 20 year old photo from East Boondockistan, this video comes courtesy of the excellent (if awkwardly titled) “Safety Academy Lab Rock” video tutorial series, produced by the well-regarded German company Ortovox, and backed by Petzl and the German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (in German, “VDBS”). So, while if Americanos like me may not have any personal experience with it, the fact that it’s featured in an instructional video made by VDBS I’d say give it a fair bit of cred.

And no, you don't truly know the quality of the steel, the length of the bolt, the type of adhesive used to glue it into the rock, etc. But, a properly placed long glue in bolt like this has a UIAA minimum standard downward pull of 25kN, and have actually tested up to 50(!) kN, which makes it about the strongest component you'll pretty much ever encounter in climbing (right up there with the huge master point ring in the Fixe anchor above.) So, the short answer is yes, you can probably rely on this single point of connection. (But, in all honesty, as an American climber raised with the mantra of redundancy, I would not be overjoyed to discover this as my only connection to the rock.)

But hey, if you find this at the top of the first pitch and you don't like it, you can always rappel off and go climb somewhere else, right? :-)

Below is the whole video; see the single point anchor part starting at 0:40.

(And the fixed point belay? We’ll cover that soon in another Alpinesavvy article.)

And, for a little historical perspective, here’s one of many single piece anchors on the iconic Matterhorn, photo by Dale Remsberg.

Stout? Looks like it.

Used by probably tens of thousands of climbers over decades, most of them professional guides? Yes.

Redundant? Nope.

anchor on the matterhorn. photo: Dale Remsberg

Make a sling anchor with just one carabiner

If you get to an anchor with chains and are low on carabiners, this crafty rope trick lets you build an anchor with just one runner and a single carabiner. (Note, this is not standard practice.)

This tip comes from AMGA Certified Rock Guide Cody Bradford.

While sadly Cody is no longer with us, his Instagram continues to stay up and is a great source of tips like this, check it out.

Note - The following tip is intended for more advanced climbers to add to the toolbox, and not meant as standard practice. Use carabiners when possible to attach a runner to bolts/chains/gear.

Someday in your climbing career, you’ll need to build an anchor after you’ve pretty much run out of carabiners.

If you have just one sling (either a double length/120 cm or a single length/60 cm) and one carabiner for the master point, you (might be) in business.

Note / disclaimer:

This example is on a bolted anchor with rap rings. The rings give a nice rounded metal edge and is bomber strong. While you could get away with it, it's not best practice to girth hitch a runner directly into a bolt hanger or to a stopper cable. If you do this and catch any sort of significant fall on the runner, inspect it carefully and possibly retire it. On the other hand, testing has shown that hitching a sling to a stopper cable can hold between about 8 kN and 12 kN, which is probably more than you think. Can a bolt hanger be much worse than that? So, like I said, something for the advanced climber’s toolbox, and not for standard practice. See the last photo at the bottom of the page for what you generally do NOT want to do.

Girth hitch a double length runner through one of the bottom rings, here the left. Try to get the runner’s stitching close to the girth hitch.

Pass the other end of the runner through the other ring, here the right.

Bring the loops together and clip your master point carabiner like so.

and tie it off with an overhand knot, done.

and here’s a video from AMGA Guide Cody Bradford showing how it’s done. (Note that Cody is using Metolius rappel hangers, which have a larger, rounded, sling/rope friendly edge than a regular bolt hanger.)

How strong is this?

I posted a similar set up to this on Instagram, and got a fair amount of disparaging comments about girth hitch weakening the sling, never put a knot in Dyneema, Yer Gonna Die (YGD), this is stupid, blah blah blah.

So, I visited my gear breaking buddy Ryan at How NOT2, and we tested it.

Well, it did break . . . the steel carabiner, at 31 kN!

That's pretty crazy so I'm gonna say it again. The steel carabiner broke before the sling! Case closed, #MoreThanSuperGoodEnough.

Here's the video from HowNOT2 to showing the testing.

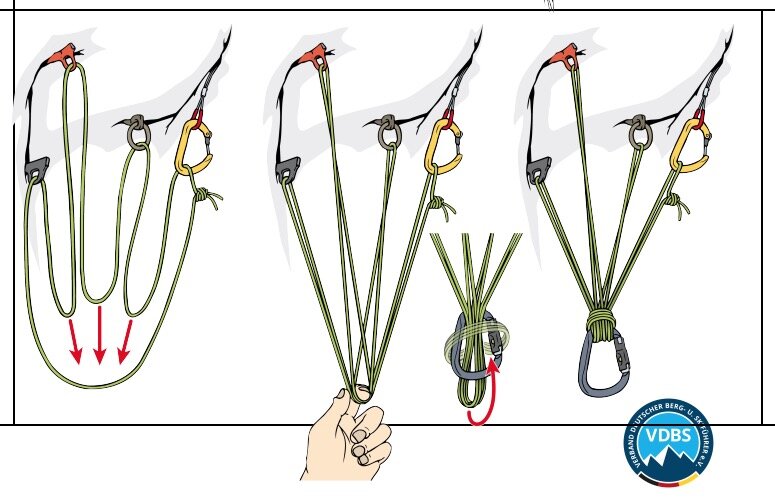

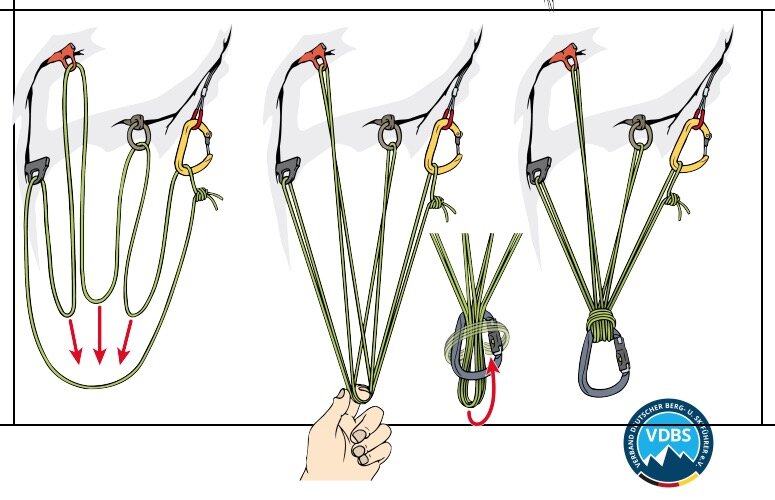

This can also work if you have two pieces that are vertically offset, or if one is a piton. Note the girth hitch at the master point. This example comes from a nice PDF file showing some European style anchor techniques, made by the German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (“Verband Deutscher Berg und Skiführer” or “VDBS”).

Supposedly, this style of anchor is more common in the south Tirol / Dolomites. In this area, the rock is often fractured or heavily featured and there's often fixed fixed gear. Using slings like this to connect directly to pitons and rings means there’s less chance of a carabiner being loaded sideways over an edge.

image: Standplatzlogik VDBS 2019 - Ausbildungsstandard VDBS & Alternativen

Other rigging options - chains and a single length / 60 cm runner

You can also do this with a single length/60 cm runner. But you won’t be able to tie it off with an overhand knot as shown above, because it's too short.

One option is to make a girth hitch at the master point, which uses less sling material than an overhand knot. (Don't freak out about this, a girth hitch is fine to use at the master point. We cover it extensively at this tip.)

Or, even easier, if the chains are long enough, you might be able to clip both of them with the single big locker and have that be your Masterpoint. Yes, it's cool to do this and don't worry about three-way loading, we cover that in this article.

Oh, and on your next lead, bring a couple extra carabiners for the anchor, will you? When your partner arrives with some extra gear and freaks out about the anchor you built, feel free to add a some carabiners from their rack if it makes them happy. =^)

If you happen to face this situation with only hangers and no chains/rings, it's still doable, but WAY Less Than Ideal. Please don't rig an anchor like this unless you really have to. Going straight through the bolt hangers is not the greatest. You may want to: 1) Check the sling after you’re done and retire if needed; 2) Brace the belay if you can with your body and belay from your belay loop; 3) Rebuild this with proper carabiners once your partner gets to the belay.

and sheesh, bring more gear with you next time, will ’ya?!

The "double top rope quad" anchor

Here's a slick way to use a quad anchor to set up two adjacent top ropes on same set of bolts.

This tip and video come from AMGA Certified Rock Guide Cody Bradford.

While sadly Cody is no longer with us, his Instagram continues to stay up and is a great source of tips like this, check it out.

Say you’re toproping with a few friends on two adjacent routes that share one common anchor. It can be a challenge to set this up so you have two separate master points, while minimizing anchor cluster.

There are various ways to rig this, but here’s one that’s exceptionally simple and clean. Use a quad anchor, and put two opposite and opposed carabiners on each pair of the quad strands.

Your quad anchor could be a large length of cord (usually 7mm) tied in a big loop cordelette style, or the new school “mini quad” typically made with a 180 cm runner, as we cover in this tip here.

To make the master points, you can use two lockers, or one locker and one snapgate. Both are fine. The choice depends on the gear you have available and your general level of acceptable risk.

Is this example “overbuilt”? Maybe. Do you have to have locking carabiners all the way around. No. But hey, if you're out climbing with several people, I bet you can come up with six lockers! To me, it's sort of like looking both ways before you cross a one-way street. Technically you shouldn't have to do it, but in reality, there's no downside to doing it, and it may give you a warm fuzzy feeling. On this website and my Instagram, I am generally going to show the most conservative approach.

No one should “safety shame” you if you decide use all lockers. (Remember, YOU are responsible for your safety and level of acceptable risk; don't let other people's opinion or what you read on the inter-web dictate that for you.)

At a top rope anchor, the anchor is “unattended” - you’re not there to monitor the rigging maybe for hours at a time with perhaps many people using it. Given this, most folks use an anchor set up that is a little more secure (i.e., more lockers) than they might for a lead belay anchor, even though the potential forces involved in top roping are much less.

Safety note: It's best to use this set up on adjacent routes, and not to have two people climb the same route at the same time on different ropes. If you were to do this, you might have a situation where one loaded rope could be running over the other rope, not good. Clipping the rope through the top bolt or piece of gear on each route as a directional can help ensure the ropes stay away from each other.

Try a girth hitch at the master point

Here's an unconventional approach to anchor building - tie a girth hitch at the master point. This has a few advantages over the standard overhand knot.

I first heard of this technique from IFMGA guide and technical director of the American Mountain Guide Association (AMGA) Dale Remsberg, and a video (see it below) made by the German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (VDBS).

Researcher and AMGA Certified Rock Guide Derek DeBruin partnered with Petzl USA to perform a rigorous analysis of the girth hitch master point. Conclusion (published September 2021), it's solid.

Why might you want to use a girth hitch at the master point?

Keeps the master point carabiner properly oriented, it can never spin and become cross loaded

Easy to untie after it’s been loaded (no welded knot to deal with)

Easier to tie and untie if hands are sore and/or cold, or you’re wearing gloves

Adjustable - If the load direction changes after tying it, you can feed slack side to side to get better load distribution

You can equalize three placements with a 120 cm runner and two placements with a 60 cm runner, if the bolts/gear are close together. Great if you are short on long slings

Redundant (even though it may not appear so at first glance. Really it is; cut one strand and it still holds, see a video testing on this below

Plenty strong (yes, girth hitching “weakens” the sling, but this is a 20+ kN runner; are you really worried about it?)

Endorsed by Climbing magazine and backed by solid research

If you try to tie a cordelette style anchor with an overhand knot in a double length / 120 cm runner clipped to three pieces of gear, the knot (almost always) takes up so much material that it can’t be tied. Given this, for a three-piece anchor, most climbers would automatically reach for their cordelette.

But, there’s another option. Provided the gear is fairly close together, the 120 cm runner works great if you make a girth hitch at the master point rather than an overhand knot.

The same technique also works with a two piece anchor and a single length runner. If you get to a two piece anchor and find you only have a 60 cm runner left, or you don't want to deal with untying a welded knot, or if you think carrying a huge cordelette is kind of a PITA, this is an solid alternative.

Let's address that “how strong is it / doesn't a girth hitch weaken the sling?” a question right off the bat. This was tested by our friends at HowNot2.com. It broke at around 28 kN.

Are you surprised by this? Think of it this way: the 22 kN sling is doubled, giving it a minimum strength of around 44 kN. Then you tie the knot which approximately by half. So, the resulting strength is somewhere in the neighborhood of the original untied sling. The takeaway: absolutely strong enough for any recreational climbing load.

Here's a break test of a girth hitch master point tied with Sterling Power Cord. This cord is great for cordelettes and anchor building. It's 5.9 mm and rated about 20 kN. Our friends at HowNOT2.com did a break test on this: 31 kN.

Common concerns and questions about the girth hitch master point . . .

- Is it okay to use a girth hitch? I thought it weakens the sling too much. The maximum load you could ever have in a recreational claiming scenario of crazy factor 2 fall onto the anchor in somewhere around 9 kN. As you can see in the image above, this anchor tests somewhere around 28, kN so no problem.

- Is it redundant? It might not appear so when you first look at it, but in fact it is. Watch the videos below. You can see one strand being cut under load and not pulling through. (Having a sling get cut like this in real life is maybe a 1 in 100,000 occurrence, but yes, it has happened.) Consider the much more likely scenario of a piece of gear pulling and then the master point being loaded. If the sling were to slip, the carabiner clipped to the gear would slowly slide and eventually be stopped by the girth hitch. Some of the videos below show the sling actually being cut. You can test this without cutting your gear, just put full weight on it after unclipping one of the pieces.

- What about the video from “How Not To Highline”, where it says the girth hitch master point is not redundant because it slips under load? Yep, I saw that video. (Ryan is a great guy and is doing some very interesting testing, I love his YouTube channel.) Yes, this method can “fail” if: 1) a sling gets cut, 2) is then subjected to a very large (6-7 kN) load, and 3) that load is continuously applied. This is applicable to a highline set up, which is why Ryan tested it, but a constant load on an anchor of 6+ kN is very hard to achieve in a normal climbing scenario. (Climb team of four NFL linemen at a hanging belay? Expedition big wall climbing with 600 kg / 1,300 pounds of haul bags, all hanging from the same anchor point? Not gonna happen.)

(Some testing where it gets impacted with a sudden dynamic load of 7+ kN would be interesting. If anyone knows of tests like that, please let me know, I think the Alpine Club of Italy has some results, I'm trying to track it down, stay tuned.)

- Did you make this up in your backyard? I've never heard of it before. It's not yet widely used in the United States, but gaining in popularity. It’s widely used in Europe. It’s advocated by lots of IFMGA Certified Guides, the German Alpine Club (DAV) and the German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (VDBS), demonstrated in the video at the bottom of the page. Do you think some of the most expert guides in the world would advocate a technique that’s unsafe?

- Can I tie it with a Dyneema sling? According to the video below made by the German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (VDBS), the answer is yes. (Some climbers suggest using a 11 or 12 mm Dyneema sling (such as the Petzl Pur’Anneau) rather than a skinny 8 mm sling, which might lessen any slippage, if that's something you're concerned about.)

- Is there a usable shelf? Hmm Sort of. Maybe. Apparently the German Alpine Club (DAV) thinks not; I’m looking for a technical recommendation on that, stay tuned. But, IFMGA Guide Dale Remsberg says yes; but to use the shelf, a load needs to be clipped into the master carabiner, so the shelf is best used to belay from. If the shelf is an anchor point for a climber, you also have to have a climber in the master carabiner. You may find if you load the shelf and the master carabiner at the same time, some wonky carabiner loading issues start to develop because they're pretty much right next to each other. A shelf is an optional feature in anchors, and very rarely a requirement. Experiment with this in a controlled environment and see what you think.

- What about adding a twist in one strand before you make the girth hitch? Does that mitigate slippage? Canadian rope solo expert Yann Camus did an interesting study that showed this in fact might help. However, a piece of protection failing and a slow steady pull causing anchor failure is not going to happen, because the carabiner attached to the protection would wedge against the hitch.

- Can I top rope on it? Yes, but it’s not so great. The main reason is that’s it's difficult to tie this around two carabiners, which is what most people like to have at the master point when top roping. The secondary reason, at least for me, is that the security of this anchor relies on the cord being firmly snugged down around the carabiner. Over the course of a long top rope session it's possible that the hitch could loosen up and start to do some strange things on the carabiner, especially if no one is there to monitor it. For a long top roping session, other options such as a quad may be preferable.

- What are the best uses for this anchor? This is best used on multi pitch climbing. It’s a good choice if you need to equalize three pieces of gear and have a 120 cm runner and not a cordelette, or if you’re climbing in cold weather and want to tie it quickly with gloves on, and avoid dealing with a welded knot.

Are you on a SAR / rope rescue team and need to maintain a 10:1 safety factor in everything you rig? Are you trying to pull your car out of a ditch? This may not be not the best anchor for you. It’s another tool in the toolbox for more advanced climbers, and not a perfect technique for every situation.

- “I dunno, it just looks sketchy.” That's fine, sometimes what we feel can be more important than what we think. Alpinesavvy offers information and ideas, not advice. If you don't like it, don't use it. =^)

Test 1: Here's an unscientific (but still quite fun) test I recently did. TWO pretty big guys, Dyneema sling, both of them loading a girth hitch master point. One strand, cut . . . no problem!

Test 2: Full weight of climber hanging from anchor, slippery Dyneema sling cut very close to the master point, no slippage. Also, no slippage when using cord. (This Instagram post has three sections, the video is in clip 2 and 3.)

Test 3: Slow pull break testing in Germany, no issues with the girth hitch slipping.

Nylon sling, 2 arm anchor, one arm clipped, failure at 15 kN.

Nylon sling, 3 arm anchor, two arms clipped, failure at 23 kN.

Dyneema sling, very short, one loop of two clipped, test stopped at 12 kN.

Hey, don’t listen just to me. How about these reputable endorsements for the girth hitch master point?

Ortovox (a German company best known for avalanche transceivers and related ski mountaineering gear) has an excellent Youtube tutorial video series on many aspects of mountaineering. The video series has the (somewhat awkward) title of “Safety Academy Lab Rock”. It's produced in partnership with Petzl and the German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (in German, “VDBS”). So, you can probably assume that the techniques shown have technical approval at the highest levels.

The video below shows various VDBS guides building multi piece anchors using an open (aka untied) cordelette.

In every case, they use a girth hitch to create the master point.

(The climber in the video is also using two techniques uncommon in the United States: 1) using an overhand knot to make a loop from his cordelette; and 2) threading the open/untied cordelette directly to the pitons / protection without using carabiners.)

Watch the video below. (The whole video is only 3:30, but if you have a short attention span, start at 1:00 and 2:00. )

Note the girth hitch at the master point in the thumbnail image below (and yes Eagle-Eye, this is for a four piece anchor.)

Dale Remsberg is an internationally licensed mountain guide (IFMGA) and technical director of the American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA). He has a great Facebook feed with regular tech tips. On it, he recently highlighted the girth hitch as a master point, calling it one of his “go to’” anchors.

Below is a screen grab of his post.

The photo and comments from Dale’s post:

image: Dale Remsberg Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10220309097824401&set=a.10204728922969767&type=1&theater

Below is a PDF article (LINK) from Erwin Steiner, a guide in the Dolomites. It's in German. A rough translation of the takeaways:

“Even when loading one arm of the anchor, it only slipped 1-3 cm”

“ . . . these tests gave us full confidence that the girth hitch can be used for anchor building. It has clear advantages in the guiding context when it comes to usability, use of material, security, speed, and comfort for the clients.”

This crafty anchor has a girth hitch on the top piton and at the master point. This image comes from a nice PDF file showing some European style anchor techniques, made by the German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (“Verband Deutscher Berg und Skiführer” or “VDBS”).

IMAGE: STANDPLATZLOGIK VDBS 2019 - AUSBILDUNGSSTANDARD VDBS & ALTERNATIVEN

Here's another image from the same PDF. Note the use of an “open” or untied cordelette, which can be threaded through fixed gear like pitons, and then tied in an overhand knot. Once again, girth hitch at the master point.

IMAGE: STANDPLATZLOGIK VDBS 2019 - AUSBILDUNGSSTANDARD VDBS & ALTERNATIVEN

Here's another nice feature of this technique. It's easy to adjust the angle of pull if it changes. Here's a nice Instagram video clip from @GoldenMountainGuides showing how that works.

I get it that everyone is not going to be thrilled with this as an anchor technique. And that's OK, you don't have to. Alpinesavvy is here to offer ideas and information, not advice.

In the end, everyone has personal accountability for their own choice of technique and level of acceptable risk. (That's why they call it the “Freedom of the Hills”, right?) But, at least be open to new ideas, especially if they come from reputable sources.

Use the rope to extend your anchor to a cliff edge

You top out on a pitch, and see a perfect tree anchor 10 feet back from the edge. Here's how to quickly rig a stout anchor that will position you in the perfect spot with a ready-made masterpoint to belay or haul.

Scenario: you’ve finished leading a pitch, and find yourself on a big ledge. You see nothing near the edge to use for an anchor, but about 15 feet / 5 meters back from the edge, there’s a nice big tree. You want to build an anchor on the tree, but then belay from the edge of the cliff. Being on the cliff edge lets you see your partner, minimize rope drag, have better belay communication, and who knows, maybe even toss the occasional pebble at them if they’re making it look too easy. =^)

Here’s one of several ways to rig this (and no, you thankfully don't need a heap of 1 inch webbing!) This assumes you have at least 30 feet . 10 meters of rope left after your lead.

Walk over to the tree, put a sling or cordelette around it, clip a locking carabiner or two to the sling, and clip the rope through the carabiner(s). Walk back toward the cliff edge. You’re still on belay the entire time.

(You could skip the sling and carabiner and just walk around the tree, assuming you can easily do this, and the tree is not going to get evil tree sap on your rope. If it’s a conifer tree, a sling might be a better choice.)

When you get close to the edge about where you want to belay, pull up a few feet of slack, and tie an overhand on a bight using BOTH strands of the rope. (This is known in some corners of the climbing world as a Big Honkin’ Knot, or “BHK”.)

Done! 1) You’re fixed to the anchor. 2) it positions you nicely on the edge so you can watch your partner, and 3) it gives you a nice master point from which you can belay your second or set up a hauling system on a big wall. (Note the ATC Guide clipped to the overhand loop, ready to belay up the second.)

What about a more exposed location?

The example above assumes a pretty large, flat ledge that you can't fall off of. If you need to approach something that is maybe downward sloping, loose rocks etc. with more chance of a potential fall, here are a couple of options.

Rigging option #1: Put a Munter hitch on the anchor, and sort of belay yourself as you walk to the edge (while remaining on belay from your partner the entire time.)

Rigging option #2: Back yourself up with a friction hitch on the backside of your clove hitch. (This might sound like a lot of fussy steps, but it's quite simple.)

Build your anchor on the tree.

Estimate how far you want to stand from the tree; in this case let's say it's 5 meters.

Pull up about 7 meters of rope.

Tie a clove hitch onto the anchor. You are now secure to the anchor, with 7 meters of rope between you and the tree.

Tie a friction hitch onto the backside of your clove hitch and clip the friction hitch to your belay loop with a locker.

Carefully walk to your chosen belay spot, sliding the friction hitch along the rope.

With the extra 2 meters of rope, tie a butterfly above you. Clip your belay device to this, pull up the slack rope, put your partner on belay.

If you need to fine-tune your position by shortening the rope a bit, you can tie an overhand on a bight to take up some of the extra rope, then remove the friction hitch.

One caution, because of the dynamic rope, keep in mind that if your second takes a big fall, the rope might stretch enough to potentially pull you over the edge. Try to keep a tight rope on your second when belaying, use an auto locking belay device such as a Black Diamond ATC guide, and try to brace your feet a bit on something if possible.

One other possible enhancement: If you have any concern about your ropes running over a sharp edge, or rockfall onto them, or if they might get damaged in anyway, or if redundancy simply gives you a warm fuzzy feeling, you could tie an overhand on a bight and clip it to the anchor point, giving you two redundant strands.

Here's a short Instagram video from Swedish guide Nikki Hammarstrom showing how it's done. (Note the pine tree - if there is any visible sap on it it's probably better to use a sling rather than your rope.)

Here’s a related technique that's more suitable when using double ropes. Put both strands of rope through the anchor, walk back to the edge, tie a double overhand loop for the belay, tie another a double overhand loop and clip it to your harness. See photo below, contributed by Alex Kostadinov; thanks Alex!

photo: Alex kostadinov

A reader mentioned to me that there is an excellent article about this at climbing.com, called “belay extensions.” Read it here.

This technique can also be used for big wall climbing, to rig a hauling a point to minimize friction.

True life story: my partner and I had topped out on The Prow, a classic big wall route in Yosemite. The last pitch concluded in a series of fourth class ledges. We set up our anchor on a tree above the ledges that made our hauling absolutely miserable from all the extra friction. Following us on the route were a team of two New Zealand mountain guides. Their leader finished, went to a nearby tree, rigged the anchor exactly as shown above, walked back down to a low-friction place to haul, and set up his hauling system directly on the overhand loop. He got his bag to the top with minimal cursing and MUCH faster than we did. Lesson learned!

Back up that single point rappel anchor

Especially on alpine routes, you can count on occasionally finding a rappel station with just a single marginal connection for the rope. There's a few ways to back it up. Here's one that doesn’t involve leaving a precious carabiner behind.

Every climber will someday find themselves at a rappel anchor that's set with a single Less Than Ideal rappel point. Maybe it's a skinny rap ring, or maybe it's a small diameter hardware store quick link, like this example.

(Note: You can buy quick links properly rated for climbing that are fine to rappel from, such as these from CAMP. These are just $3, CE rated, and around 40 kN - a much better choice than one from the hardware store.)

You have a choice: Rappel on that one point, or back it up somehow.

Now, lots of people are going to be just fine rappelling from a single quicklink. For canyoneers it’s common, and it's probably going to work great 99.9% of the time. But, if you're a more conservative climber, for whom redundancy in anchors gives you a warm fuzzy feeling, especially when you are completely reliant on them when rappelling, you have a few options.

Note: It's best practice to close the sleeve of the quick link by screwing it down toward the ground. This means that gravity is helping keep the sleeve closed. A little pneumonic to help remember this is: “Screw down so you don't screw up.” If you have a link that you want to fix it more permanently, give it an extra turn with a pair of pliers; a multi-tool is your friend.

If you want to back up that one point, the easiest thing to do is sacrifice a carabiner off your rack and just leave it. Unless you’re a serious cheapskate, this is typically the best option.

Or, you could back it up with a carabiner for everyone who is rapelling except the last person, and then that last person removes the carabiner and raps on the single quick link. (The traditional rule of thumb for this is that the lightest person goes last. I have a feeling this rule was made up by heavy people.)

But, for the frugal climbers out there who can't even stand to part with a $5 carabiner, here's another option.

Cut about a bit under 2 feet of cordelette, sling, or whatever reasonably strong cord you have with you. (Yes, that looks like it's going to be too much, and no it won't be, ‘cuz water knots always take up more webbing than you think they will.) A rule of thumb in the field: measure about three hand spans, my hand span is about 7 inches. And yes, you do need to have a knife for this.

This is yet another reason to bring along an '“alpine runner,” a 9 foot length of 9/16” tubular webbing, tied in a double runner length loop. It's very inexpensive and easy to cut up and leave behind for little projects like this.

Tie it in a loop (here with a water knot) through the anchor point, and make the loop a little bit longer than the metal connection.

Now, thread your rappel rope. Because the backup webbing is slightly longer than the quicklink, when you weight the anchor and pull your rope, any friction is going to be on the quicklink, not the webbing backup. However, if the metal were to somehow fail, the webbing will catch the rope.

Doing this of course, takes a knife, and some sort of extra sling material, and the time to rig it. Like I said, faster and probably a bit safer is just to leave a carabiner. Don't be a cheapskate. :-) Or, if you want a little extra security even on top of that, put some tape on the carabiner gate to make a cheapskate locker.

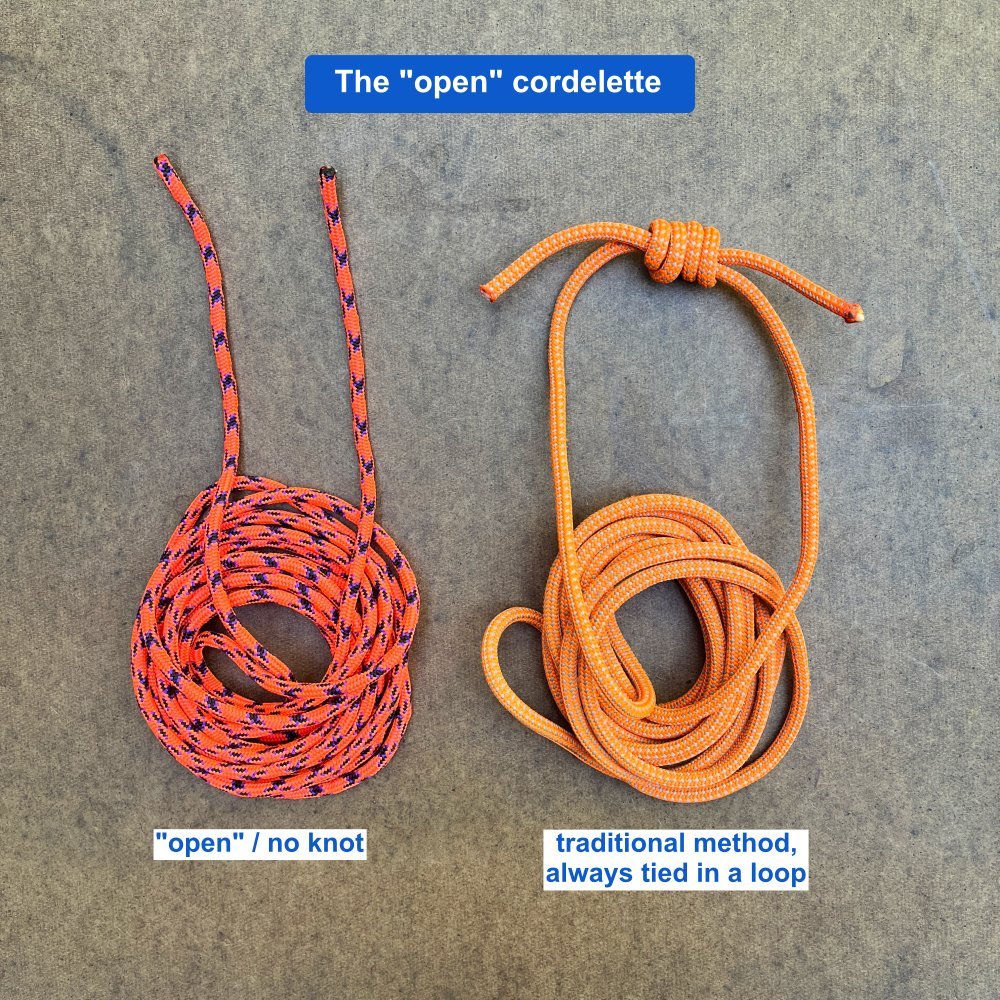

The "open" cordelette

There are many variations on anchor building with a cordelette. How about carrying it with no knots at all? Here's how to build a fast, secure anchor with an “open” cordelette.

While a traditional cordelette is about 16 feet of 7mm cord tied into one big loop, many climbers (if they carry one at all) prefer to leave it untied, known in some circles as an “open” cordelette.

Why use an open cordelette? It’s more versatile.

You can tie the ends together quickly in a big loop if you need it, with a simple flat overhand bend. (That’s right, no double fisherman’s knot required.) It’s fast to tie and easy to untie when you’re done compared to many other knots.

You can tie small loops in either end to make a ”bunny ears” cordelette. This can be handy when the gear is far apart, or you need to sling a big tree or boulder. Just tie a small overhand loop near the ends.

“Bunny ears” used to clip gear that’s far apart.

Ice climbing toprope

If you're setting up an ice climbing top rope anchor, you can make two V thread anchors and connect them both with a single cord, if you keep it untied.

Photo credit, Tim Banfield and Sean Isaac

Thread the open cord through fixed protection

This example comes from a nice PDF file showing some European style anchor techniques, made by the German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (“Verband Deutscher Berg und Skiführer” or “VDBS”). Here, using an open cordelette lets you thread one and through the fixed gear that can’t be clipped. Also, note the girth hitch at the master point.

image: Standplatzlogik VDBS 2019 - Ausbildungsstandard VDBS & Alternativen

Crevasse rescue

After a crevasse fall is held by the team on top, the person closest to the crevasse can tie a prusik hitch with an open cordelette (about 5 meters of 6 mm cord) on the rope, tie an overhand to make a clipping point, and tie the ends through their belay loop.

The key here is that the ends can be passed through the belay loop and tied if needed in a rescue; the rest of the time it stays out of the way on your harness.

Image: https://www.ortovox.com/uk/safety-academy-lab-ice/chapter-3/rescuing-a-companion

Alternative anchor rigging

You can make an multi point anchor by not really tying any knots at all at least until the master point. Here's one way to do it, shown by my pal Ryan Jenks at HowNot2.com. It's a little hard to explain in words, so check out the video below.

Spoiler alert: 28 kN strong anchor made with 6mm cord, impressive!

Start it at 7:00.

Here's another way.

Place three pieces of gear, or in this case, three bolts. At least 1 foot from one end of the cord, tie a clove hitch and clip it to the left bolt. At least 1 foot from the other end of the cord, tie another clove hitch, and clip it to the right bolt. Then, take the approximate middle of the cord and clip it to the middle bolt.

Clip a locking carabiner through the two “U” shaped strands in the middle.

Tie an overhand knot (or figure 8) to make the master point. Done!

Note:

There is no redundant shelf on this anchor. The loop that goes from the masterpoint knot to the middle bolt is probably okay for clipping a backpack, but not for belaying.

This anchor is easily adjustable. If the pieces are far apart, or farther away from you, tie the clove hitch nearer to the end of the cord (while still leaving a foot or so of tail, and snugging down the knot.) If, like in this case, the pieces are very close together, you can tie a clove hitch with longer tails, making a more compact / higher master point.

This anchor can be easily adjusted if the direction of pull changes. If the direction of pull changes to one side, say the left, then the strand of cord going to the left anchor is going to go slack, which means it's not taking any of the load. You can easily adjust this by shortening the clove hitch going to the left bolt, which can regain a nice three point load distribution.

You only have about half rated strength of the cord going to the single arms. A 7 mm cord is rated about 13 kN, so half of that is around 6.5, which should be fine. However, a 6 mm cord is only rated 7.5 kN, so halving that brings it down to 4 kN, which is sort of in the danger range. So, if you're ever going to use this technique, please use a 7 mm cord.

Hey, don't take my word for it. Here's a short (31 seconds!) video by expert climber Hans Florine (multiple speed climb record holder on The Nose on El Capitan, among other things) showing this technique.

Using a rope to make a tensionless tree anchor

Do you need to fix a rope and have a stout tree available? Lucky you - this is probably the simplest and strongest anchor you could ever build. Just watch the sap on those pine trees . . .

Need to secure the end of a rope around a stout tree? Provided the tree is not oozing with sap, and you have a bit of extra rope, here's a good way to do it.

This is known by some as a “tensionless” anchor, because there is no knot that's under load or tension. I prefer to call it the “tree wrap”, as it's more descriptive. This is one of the strongest anchors you can build, because you’re using the entire strength of your rope, with no loaded knots which weaken it. One main benefit, it's very easy to untie when you're done, even after a huge load.

First off, have a good look at the tree. The American Alpine Institute blog has a good memory jog for this, "Five-and-Alive." The tree should be at least 5 inches in diameter, 5 feet tall, and alive with a good root base. Be wary of trees that could have a shallow root-base, in dirt, sand and/or on top of a rock. Thanks AAI, good advice! (Personally, I’d consider a 5 inch diameter as the absolute minimum, larger is better!)

Starting with one end of the rope, take a few coils in your hand, and pass them around the tree trunk 4-5 times. This may well take more rope than you think, so start with a bit extra. Tie a figure 8 on a bight or overhand in the end of the rope, and clip this bight to the load strand with a carabiner to close the rope system.

If you tie this correctly, the friction alone from the rope on the tree bark will support the load, and the carabiner at the end should never see any force at all.

Rigging this close to the base of the tree reduces leverage and increases strength. This is more important if the tree is at all marginal. (If the tree is unquestionably strong, it doesn't really matter.)

Try four wraps as a minimum to start. Add more if needed.

Try to keep the loops reasonably tidy, but if they get a bit crossed up it's still going to be fine.

This should not damage the tree (especially if it's one part of a multi piece anchor) because the force is spread out over many rope strands, and not gouging into the bark. If you wanted to be extra nice to the tree, feel free to put in a backpack or something similar between your rope and the tree trunk.

If you're doing this on a conifer tree, there's a good chance you're going to get sap onto your rope. YUCK! This is something you want to avoid if at all possible, so try not to use conifer trees.

If you do get tree sap on your rope, hands or anywhere else, you can use mayonnaise, believe it or not, to clean it off quite effectively.

Another good option to secure the end of a rope around the tree is a bowline, either one strand or two.

If you REALLY want to go with elegant minimalism, you can skip the carabiner entirely, and tie a rewoven figure eight around the load strand. That's pretty cool, an anchor you can hang a truck from that doesn’t use a single piece of metal!

Cordelette on a tree: caution on the shelf

Passing a long cordelette loop around a stout tree and tying off with an overhand knot is an excellent way to make an anchor. However, if you want to use the shelf, you want to think carefully about where it actually is. It may not be where you think.

Say you have a standard cordelette tied in a big loop, and you want to use it to build an anchor on a stout tree or a rock pillar, aka a “monolith” (one piece) anchor. If you pass the cordelette around the tree and tie it off in an overhand knot, (or double it and loop it over the rock pillar) it might seem that you have a bomber shelf if you clip one strand on the left and one strand on the right, just like when you clip two separate pieces of gear.

But be careful, it’s not what it appears. If you clip the two strands like you would for a gear anchor, there is a 50% chance you're going to be on just ONE strand of the cord, and therefore not redundant.

See the photos below.

I have to say, I was scratching my head a bit when I first heard of this. I had to set it up on a tree in my yard to see for myself.

After you read this, you may think that any anchor failure like this in the real world is so extremely unlikely that you're not going to worry about it. Well, that may well be true. However, this is not a very intuitive thing to grasp for most people, and I want to illustrate best practice in all aspects of anchor building. So, absorb it if you want and toss it if you don't. :-)

Here's an Instagram video I made that shows it pretty well, with one strand of the cordelette wrapped in blue tape, to hopefully make it a bit more clear.

Long cordelette looped around a tree, tied off with an overhand knot and locking carabiner as the master point. Perfect.

Hmm, thinks the climber, I think I want to add a shelf. How about I clip another locker to the two strands coming out of the top of the master point? Well, doing this is not a lethal mistake, but if you think you’re getting redundancy on two rope strands, you only have a 50% chance of doing so.

As it's shown here, the top carabiner appears to be clipping two different strands, but it's actually clipping the same strand twice - not redundant, whoops! You can't see it in the photo without a video walk-around the tree, but you can easily set it up yourself to see what I mean.

Here, the black carabiner is clipped correctly to both strands coming out of one side of the masterpoint knot. It's clipped to both strands, giving redundancy. Yes, if you're a long time cordelette user and have always used it to clip single pieces of gear, this photo below is probably giving you a minor freakout. Trust me, it's right, and set it up for yourself to see how it works. You can do it inside around a chair or pretty much anything.

(Of course, there's no reason to really use the shelf at all. In most cases, it's an optional nice thing to have but certainly not a mandatory part of the anchor. So, if this post is making your eyes cross, you could go back to the photo at the top, with no mention of the shelf at all, build an anchor like that and be just fine.)

A slick way to build an anchor from the rope

Making an anchor with only the rope and a few carabiners can be a very useful skill. Here’s a Crafty Rope Trick (CRT) that does this with just a few carabiners and knots you already know.

There are lots of ways to build an anchor with just the climbing rope. You could use a bowline on a bight, or a “bunny ears” figure 8, as discussed in this post. Either of these gives decent load distribution, but they do require that you learn new knots that some people find a little tricky.

Here’s a slick method to make an anchor with the climbing rope that simply uses clove hitches and a butterfly or overhand knot, which you hopefully already know. (If not, check out the video section.)

One good reason for using the climbing rope as your anchor: if the climbing is tough and run out right off of the anchor, and thus a greater chance for a leader fall to put a large amount of force onto the anchor and belay. Having the entire anchor made out of dynamic rope gives more stretch to the system and will lower the force on all the other components.

There are a few downsides to rope anchors:

It works best if you’re swinging leads on a multipitch climb. If one person is doing all the leading, or if this is the last anchor at the top of a climb and you’re transitioning to rappel, it’s better to craft an anchor from a sling or cordelette so you have both ends of the rope to work with. (Even if you plan on swinging leads, your partner might decide they don't want to take their turn and you might have to go again, so keep that in mind.)

If the next pitch is a real rope stretcher and you might need every bit of it, this may not be the best choice.

When the leader pulls up the rope on the second, the rope pull come tight first onto the anchor and not directly onto the second climber. This can create a few meters of potentially unwanted slack when the second breaks down the anchor. The second can clip in to one bolt or piece of solid gear with a tether before they remove the anchor as a possible solution.

Rope anchors can make any sort of self rescue technique more challenging, because the end of the rope is a component of the anchor. Yes the belayer can can simply untie and they're out of the system, but then they’ll have a harder time using the rope for much of anything useful.

Say you’re leading, and arrive at a two bolt belay anchor. Here’s what you do.

Clove hitch the rope (that’s tied to your harness) to a bolt with a locker. Clip a second locker onto the second bolt.

Maybe 6-8 inches inches on the “backside” of this clove hitch, tie a bight knot. Here I tied a butterfly knot, but it could be an overhand or figure 8 on a bight.

Next, clove hitch the rope to the second bolt. Adjust the clove as needed to center the loop.

Clip a plaquette style belay device to the butterfly, and bring up your partner.

Done! You’re connected to both bolts, and you have an equalized master point. You hopefully set this up in under one minute, and used a minimum amount of gear.

How to rig a "courtesy" anchor

Extending a rappel anchor master point over a ledge can make for an easier rope pull, but a tougher start to the rappel. Rigging a “courtesy anchor” can make things easier and safer for just about everyone. (Sorry there, last person . . . )

This tip comes from my pal and canyoning expert Kevin Clark. Check out his excellent book, “Canyoning in the Pacific Northwest: A Technical Resource.”

A “courtesy anchor” is a concept from the canyoneering world, where generally a LOT more thought is given to rappel technique than is typical in rock climbing. It’s not something you’ll rig very often, but in certain situations it's a very #CraftyRopeTrick to have in the toolbox!

Imagine this scenario: -A rappel anchor has a long extension on it, maybe webbing or chain. The purpose of the extension is to hang the anchor master point out over the cliff edge, making it easier to pull the rope. The problem: this probably will make an awkward start to the rappel, because the master point is hanging out into space rather than being on on the actual anchor, which is set back on a nice flat ledge. (In the Portland Oregon area, the rappel off of Rooster Rock in the Columbia River gorge is a great place where you can use this technique.)

The “courtesy anchor” is a simple solution. The main benefit: only one person on the team (ideally the person with the most experience, who goes last) has to perform the awkward rappel start. Everyone else can begin their rappel at the actual anchor point, away from the edge of the cliff. There’s no need for everyone on the team perform an awkward / dangerous / difficult start to the rappel.

There are various ways to rig this. Here’s one of them.

Add a carabiner onto the upper anchor point, and then bring the rappel master point back and clip it to this added carabiner.

This allows every person but the last to start their rappel on a nice flat ledge rather than shimmying over the edge. The last person to go, hopefully a more experienced and skilled climber, removes the courtesy carabiner, extends the master point to its original position, and makes the awkward start to the rappel.

The last person has a few options to reduce their risk.

Get a firefighter’s belay from below

Lock off their rappel device with a mule knot (or similar)

Tie a hard backup (aka catastrophe knot) / overhand loop with both strands of the rope, about 10 feet below the edge, and clip that to their belay loop

Put a klemheist knot or some other friction hitch that is releasable under load above their belay device

Or some combination of the above

If all goes as planned, this makes a faster and safer rappel for just about everybody. Except the poor suckah’ who has to go last . . .

Here’s how it works.

This anchor as shown is great for pulling the rope because it extends the master point over the cliff edge. But it can be awkward to start your rappel.

Clip a locking carabiner to some point on the orange cordelette. There are several places where you could clip, here I’m using the shelf.

Another option is to basket hitch a long sling higher up on the tree, assuming the tree is strong to handle the increased leverage. (Having an attachment point higher up makes it even easier to start your rappel.)

Pull the rappel masterpoint quicklink up, and clip it to the locking carabiner. Doing this allows everyone except the last person to start their rappel right at the anchor. The last person removes the sling and carabiner, extends the master point to the edge of the ledge, and performs the somewhat awkward rappel start, leaving the rope in a better position for a successful retrieval.

Finally, here's a nice video by canyoneering expert Rich Carlson showing a few different ways to rig it.

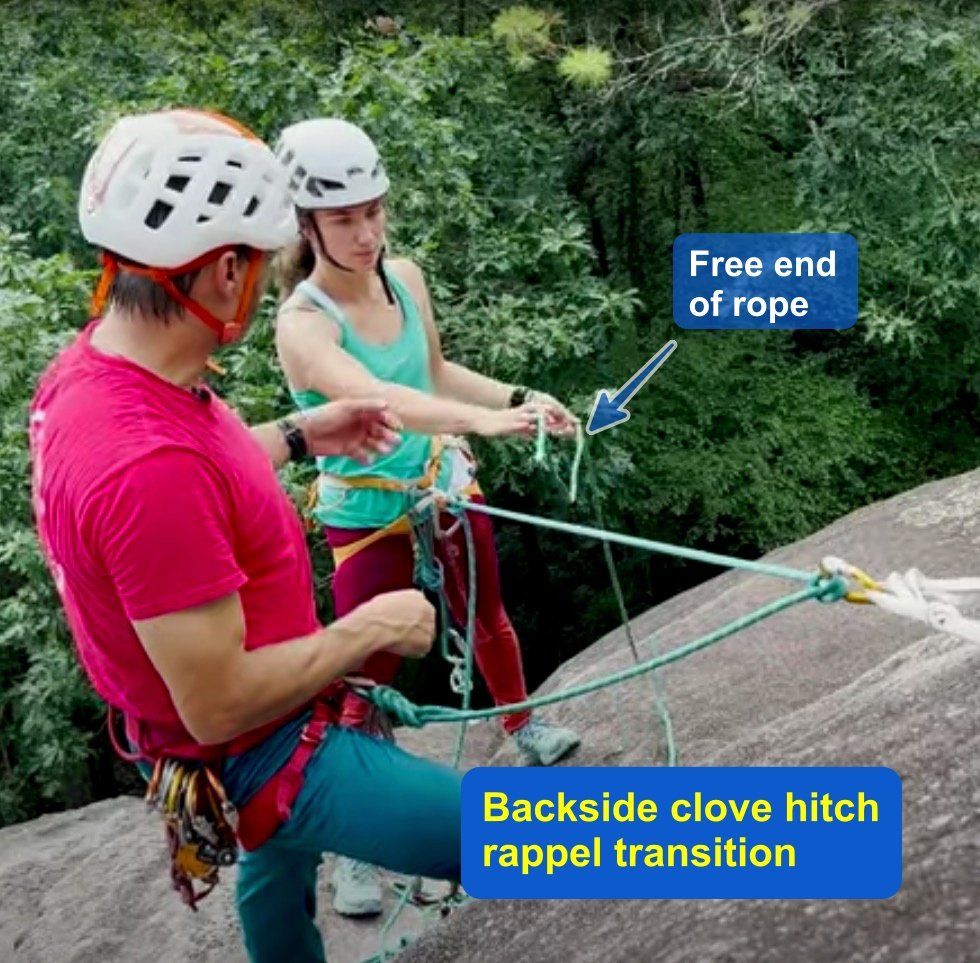

Backside clove hitch: transition to rappel

The “backside clove hitch”? Is that something you might find in a San Francisco leather bar? Nope, it's a new approach to transitioning from climbing to rappelling. It has a host of subtle benefits, and it's a Crafty Rope Trick well worth adding to your toolbox.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

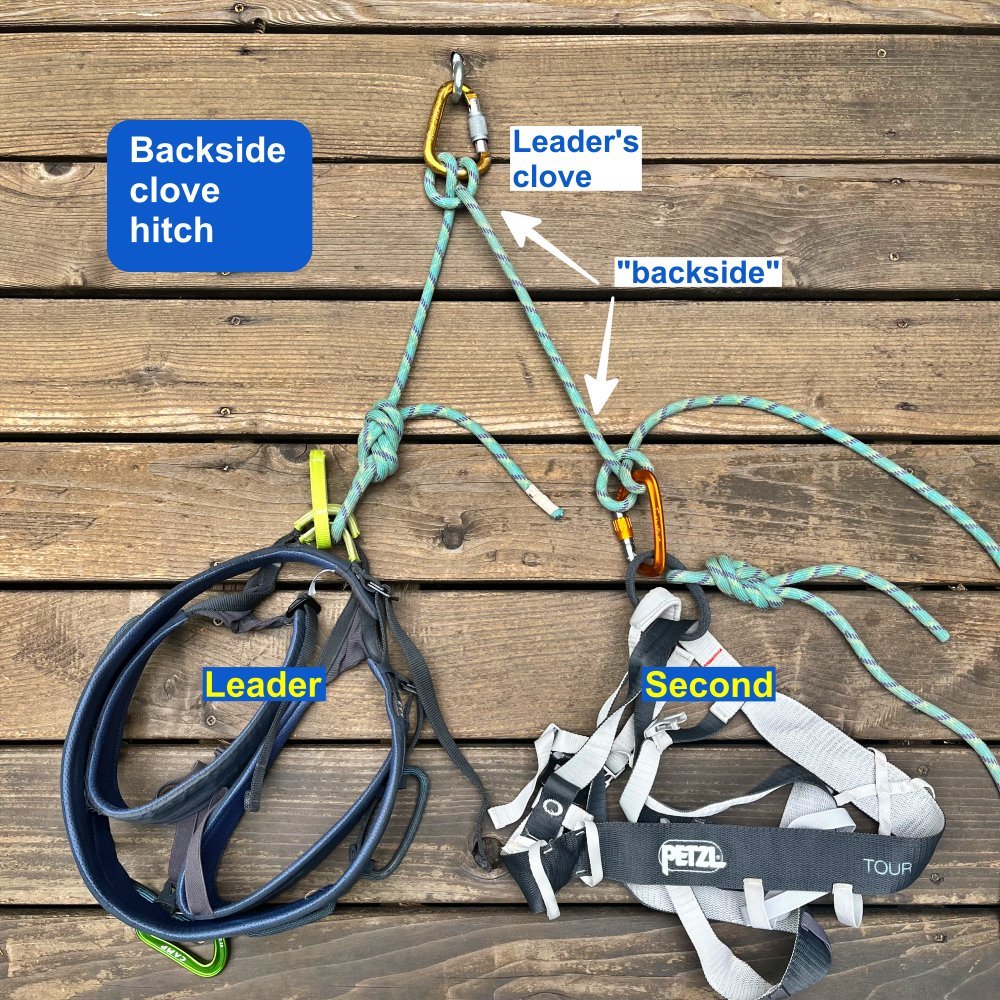

Using the backside of the leader’s clove hitch is a great way to transition from climbing to descending.

Advocated by IFMGA Guides Marc Chavin and Rob Coppolillo (authors of the excellent book “The Mountain Guide Manual”) this method uses the climbing rope coming off of the leader’s connection to the anchor as the primary anchor point for the follower, as opposed to the second clipping a tether to the anchor master point.

Lots of multi pitch routes require a rappel to get down. For many climbing teams, this transition period, from moving upwards to moving downwards, can be a bit of a cluster.

The traditional method is each climber using a tether/PAS to connect in close to the anchor, each person untying from their respective ends of the rope, threading the anchor and then each person rigging for a rappel separately. This can be awkward at tight stances, and often takes a LOT longer than necessary, especially with less experienced folks.

The backside clove hitch elegantly address some of these issues.

(Another term I've heard for this method is the “Backside Rappel Feed”, or BARF. I love it, but it hasn't caught on yet.)

It can take a bit of creative visualization to try to imagine how this works in your head. I have to say it took me a while before I got it figured out. But once I did, and realized the subtle benefits that come from this system, I knew it was going to become a regular part of my rappel routine.

I strongly suggest you try it on flat ground with a partner a couple of times to get the hang of it, and watch the video at the bottom of this page!

What are some benefits of the backside clove hitch?

1 - Cluster free anchor. By having the follower clipped to the backside of the leader’s rope, there’s no need for multiple leashes clustering up the anchor. You have plenty of room to stretch out and move around a bit, assuming the ledge allows you to do so. Your position isn’t limited by a short tether or PAS.

2 - Always using the dynamic rope to connect everyone to the anchor. Ropes are stretchy. Generally, tethers and slings, not so much. Stretchy is good. Use it when you can.

3 - (Close to) zero chance of dropping the rope. For a two person team to transfer to a rappel, of course one end of the rope needs to be freed up to pass through the anchor. With the backside clove hitch, this is simple: because the leader’s end of the rope is securing the entire team to the anchor, the follower’s end of the rope will always be the one threaded through the anchor. The leader remains tied to their end during the whole process. Rule number one in setting up a rappel is don’t drop the rope, and this method pretty much ensures that can never happen.

4 - Faster and less risky rappelling. After the follower threads their end of the rope and and pulls to the middle point, both climbers can rig for rappel. A low risk and fast way to do this is to rig an extended rappel with both climbers doing so at the same time. The extended rappel means climbers can check each other, which reduces risk. Because they both rig for rappel at the same time, and also increases speed, because the second can begin their rap the moment the first person is at the next anchor.

Here’s the general procedure:

When the leader is securely attached to the master point with the clove hitch, they tie a clove hitch or a loop knot (overhand, fig 8, butterfly, your choice) on the backside of their clove hitch connection. This hitch/knot gets a locking carabiner.

The second arrives at the anchor, and clips this locker to their belay loop.

The leader takes the follower off belay, and removes the belay device from the anchor.

The second unties, freeing up a rope end.

The team threads the rope end through the anchor, pulls it to the middle point, and tosses that strand.

Both climbers rig an extended rappel and a third hand backup.

Both climbers are now secured by their extended rappel. The second removes the hitch/loop knot and carabiner from the backside of the leader’s clove hitch. The leader unties, tosses down the second strand of rope, and cleans the anchor.

Do a safety check, and rappel.

In the video below, the second climber rappels first. However, there can be some advantages for the leader descending first. Here, the leader remains tied in the entire time, the second rigs their extended rappel above the leader. Doing this has a few extra benefits:

The leader can’t rappel off the end of the rope, because they are tied to one strand and it's blocked from above by the second.

It's a bit less rope management, because you only have to throw one strand instead of two.