Alpine Tips

Ice climbing - environmental “red flags”

As ice climbing season winds down, it becomes more important to consider environmental conditions as potential hazards. Here are five of them. Guest post from IFMGA Guide Kel Rossiter.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

This post (shared with permission) is an Instagram post from Kel Rossiter, an IFMGA guide and owner of Adventure Spirit Guides. Connect with Kel on his website and Instagram, @adventurespiritguides

Photo: Capt. John Crowley/Duchesne County Sheriff's office

Kel Rossiter writes:

“We're moving into transition season here for ice climbing. Recently, I was asked to name the environmental factors to get my attention relating to hazards. These are the five I came up with.

The field of avalanche science has a lot to teach the climbing community in terms of risk analysis. One tool they use are the “red flags” - things like wind, heavy snowfall, etc. that should serve to get skiers attention when deciding when and where to go.

There are similar red flags in ice climbing. I came up with five, there are likely more.

Nighttime temperature above freezing

Daytime temperatures above about 40F/4C

Rain

See Premium Member article

See Premium Member article

The first three red flags have to do with warming, obviously not good for ice, which substantially increase overhead hazards.

Red flag number four . . .

Red flag number five . . .

None of these red flags are showstoppers for me. But if several of these are stacking up, it's a sign to me that I might need to change venues to shady places, a place with less overhead hazards, etc. And although I did throw out the number of 40°F/4 C, this is of course not an exact science.

There are other hazards in ice climbing, such as avalanches, cold temperatures leading to frostbite and hypothermia, and high consequence of falling. These are different than an environmental red flag, meaning hazards that have a direct effect on the ice I intend to climb.”

Want to see the environmental hazards #4 and #5?

Join my Premium Membership to read the complete article.

Thanks for your support!

Three ways to equalize crevasse rescue anchors

In crevasse rescue, you often build one anchor and transfer the load to it. Then (if needed) you may build a second anchor and try to equalize #1 and #2. Here are three methods to dial in this equalization.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

While anchors for crevasse rescue operate on the same principles as other anchors, equalizing a loaded placement can require some different methods.

If you’re building a two piece snow anchor and want to equalize / share the load between them, you can treat it pretty much like a rock anchor. Place your two pickets, deadman, buried skis, whatever you‘re using, connect the protection with a cordelette, long sling, or your rigging of choice to make a master point, and there you go.

However, in crevasse rescue, this is often not the best approach. The above method can take a lot of time, digging, and packing down of snow. This is all happening while your unfortunate partner is in the hole, and hopefully your other teammate(s) on the rope are trying to keep them from slipping down any further.

So, for crevasse rescue, the typical approach is:

Get one anchor in fairly quickly. (If the snow is reasonably dense, this can be a vertical picket.)

Transfer the load to that, ideally with one team member sitting in the snow behind it to back it up.

Then, if you think it’s needed, a second anchor can be made and equalized with the first one.

Here's the tricky part: because there's already a load on anchor #1, it can be difficult to get the length of the sling or cord from anchor #2 JUST right to have proper load equalization / sharing.

Here are a few ways to fine-tune the connection between the anchors so you can get a decent load distribution.

In these examples, I'm using what I call a “crevasse cord”. It's basically a mini cordelette made from ultra-strong cord. My preference is about 10 feet / 3.5 m of Sterling VT-X cord. It's 5.4 mm, rated to 15 kN, and has a Dyneema core with a polyester sheath.

This is carried “open”, or untied, not tied into a semi-permanent loop.

Because this cord is so strong, you can rig it “bunny ears” style, with a small overhand figure eight on a bight loop in one (or both) end(s). Rigged like this it’s still probably good for 8+ kN, which is a much higher load than you should ever experience in a crevasse rescue scenario.

The standard cordelette you might use for climbing, which is about 6 meters of 7 mm cord still works fine for crevasse rescue. But I find it heavy, bulky, and usually too long; I prefer a smaller length of the Sterling VT-X.

Method #1 & 2: Clove hitch or trucker’s hitch

Clove hitch: This is probably the easiest method and uses a knot you already know. Tie a bight knot in one end of your crevasse cord. Clip that knot to the carabiner on anchor #2. Tie a clove hitch and clip it to anchor #1. Feed cord through the clove to remove as much slack as you can in your crevasse cord.

Trucker’s hitch: The trucker’s hitch isn’t used very often in climbing, but it's a super handy knot to know for lots of other life applications. This also does a little better job than the clove hitch to actually share the load between the anchors. Just like above, tie a bight knot in one end of your crevasse cord, and clip that knot to the carabiner on anchor #2. Pass the other end of your cord through the carabiner on anchor one. Tie a trucker’s hitch to put tension on the crevasse cord.

Here's a video showing the trucker’s hitch method. It starts about 11:30.

Method #3: Alpine block and tackle

Want to learn about the alpine block and tackle, and see a video of how to set it up for crevasse rescue equalization? (Sure you do!)

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

How strong is a “stabbed” rope?

Plodding along on a glacier climb, you get a little careless and CHUNK, your crampon spike goes straight through the middle of the rope in front of you. Does this dangerously compromise the strength of your rope? I tested it with HowNOT2, here are the results.

Premium members can read the complete article here:

Scenarios for a “stabbed” rope . . .

Top rope ice, climbing, you carelessly swing your tool, and CHUNK, you drive your pick straight into the rope. Whoops!

Walking in a rope team on a glacier. A careless step and you stab the rope with your crampon. Whoops!

If you do either of these, does it completely compromise the strength of your rope?

I've always wondered about this, so I tested it on my latest visit to the gear-breaking mad scientist genius Ryan Jenks from HowNOT2.com.

The rope we tested was a Beal Opera 8.5 mm, common for glacier travel.

Disclaimer, yes, results will probably be different depending on rope diameter, size of the spike, type of sheath used in the rope, etc. We had a small sample size. This is what we got, don't take it as gospel.

Test 1: Crampon stab through the rope?!

Broke at 11.9 kN. It broke in the knot, and NOT in the “stabbed” part of the rope.

That's close to full strength of the rope.

Click image below to see the short video.

Want to see the break from Test 2, pounding a nail multiple times through the rope?! Or test 3: ridiculously beating on the rope like a manic woodpecker in the same spot with an ice tool?!

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

Can you girth hitch a Dyneema sling to a picket?

Can you tie a sling directly to a picket hole? Is it going to be strong enough to catch a fall or use as a anchor in crevasse rescue? I did the testing, and have a broken picket to prove it.

Premium members can read the complete article here:

If you’re trying to shave weight on an alpine climb, you might wonder: is its okay to girth hitch a sling directly to a picket?

(Yeah I know, cool Euro climbers don't use pickets and make an anchor out of their buried ice axe, cigarette pack, or whatever, but that's a different topic.)

Does this dangerously weaken the sling?

Is the sling gonna get cut on the sharper bend radius of the picket hole?

Should I use the sling full strength (about 22 kN) and clip it with a carabiner like normal?

All good questions! I was curious about them as well. So I took a visit to the gear breaking lab of mad scientist Ryan Jenks, aka Mr. HowNOT2, to find out.

We used older Dyneema slings hitched through the middle hole on an older style MSR Coyote picket.

The girth hitch tested at a bit over 10 kN.

(Yes, with a limited sample size of 1.) For me, that's acceptable for a crevasse rescue anchor, because your picket is going to pull out of the snow before you approach that much force.

Not that you should ever be generating a load like that in a standard crevasse rescue to begin with . . .

But hey, if you want to use the sling full strength at 22+ kN, then clip it to the picket with a carabiner, your choice!

Next we tried a basket hitch. As expected, that was a bit stronger, around 16 kN.

After that, just for fun, we doubled the sling through the hole; a double basket hitch. (Yes, we kept using the same picket for every test, so it might've been a weakened after the first two .)

Here's what happened. The sling it was fine. The picket broke 18.4 kN!

Want to see a YouTube short showing the break test, and a way to tie this with a bowline?

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

Crevasse rescue: simplified drop loop 2:1

The progress capture on a hauling system does not necessarily need to be on the anchor. If you have it on a fixed strand of rope, you can simplify your rigging, reduce friction, and lower the load on the anchor. Here's one way to set it up for 2:1 crevasse rescue.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

Here's a simple method to create a progress capture on 2:1 hauling system that uses minimal gear, is fast to set up, and puts minimal force on the anchor.

Advantages to this system:

Uses basic gear you’ll always have: one friction hitch and one carabiner.

Doesn’t require a specialized and expensive progress capture pulley.

About the simplest and least complicated rigging possible.

Because there's no redirect, you eliminate this friction in your haul system, AND put the smallest possible load onto the anchor. A redirect puts 2X your pulling force onto the anchor. No redirect means a reduced load on the anchor. That's a good thing.

Modern equipment, such as the Petzl Traxion progress capture pulley, are superb tools for self rescue. They are small, lightweight, cool (because they‘re French!), and they work great.

However, they are expensive, you may not have one when you need it.

Especially with skills like crevasse rescue, a good approach is to learn it first with the bare minimum of gear, and then add fancier tools after you have the basic mechanics dialed.

As climbers, we’re often locked into the idea when we build an anchor, all the important things must happen actually ON that anchor. For example belaying up your partner, and having the progress capture in a hauling system.

However, it doesn't have to be that way. Often, we can use a fixed strand of rope, instead of the anchor itself.

Doing this can create many interesting options, which may make your rigging more efficient, comfortable, or ergonomic.

Let's have a look at the basic mechanics of the 2:1 drop loop.

When one strand of the rope is fixed to the anchor, and a loop is on the load, and you pull on the other side of the rope, you create a 2:1 mechanical advantage.

If you pull 2 meters of rope, the load moves 1 meter.

In a theoretical frictionless world, you can move a 100 kg load by applying about 50 kg of “pull. ”

In the real world with the friction of a carabiner on the load, your actual mechanical advantage around 1.5:1.

When you're pulling, you’re lifting about half the weight of the load, and the remaining half of the load is on the anchor.

Check out the photo. Note that one side of the “C “ is fixed to the anchor, the other side you can pull.

The “pull” side moves, and the “fixed” side doesn't.

This means that you can use the fixed side to attach your progress capture. This is the key to the simplified method.

Here's a step-by-step of how to set up a simplified 2:1 drop loop.

Step 1: Tie the rope to the anchor.

This could be the end of the rope, or any point along the middle of the rope (as shown here) and would be typical in a crevasse rescue. Be sure you have at least twice as much rope between you and the load.

Step 2: Clip a loop of rope to the load.

In a crevasse rescue, this would typically be lowered down to the victim. If you have a pulley to minimize friction, this is a great place to use it. If you don't, it still works, but you need to pull a little harder.

Step 3: Tie a bight knot to the “fixed” strand of rope.

This is the side of the “C” that’s tied to the anchor, and it doesn’t move when you pull. Here I tied a butterfly because it's easy to untie after it's been loaded. A figure 8 or overhand works fine as well.

Tie this knot at any convenient spot along the fixed rope. Make the loop small, like fist sized.

Step 4: Tie a prusik (or attach a Traxion) to the “pull” strand of rope.

This is the side of the “C” that’s returning to you from the load, and moves when you pull. Use a prusik rather than an autoblock or klemheist, because it usually grabs the best and you don’t want this knot to slide/creep when weighted.

Here I'm using a Sterling Hollowblock which is quite short. Short is good.

If you have a progress capture pulley like a Traxion, put it on the “pull” strand and clip it to the bight knot with a locker. (This actually works better than the friction hitch, but for this example I’m showing simple gear.)

There are several more steps involved in reading this correctly.

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

The "crevasse cord"

A standard cordelette (6-ish meters of 7 mm cord) is good for rock climbing. But it's unnecessarily long and bulky for glacier travel and crevasse rescue. Here's an alternative: about 3.5 meters of 6 mm Sterling V-TX cord, rated at 15 kN. This cord is short, light, compact, versatile and great for crevasse rescue.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

For a long time, and without giving a lot of thought to it, I carried a pair of 120 cm slings or standard cordelette (about 5 meters of 7 mm cord) on glacier climbs.

Recently I’ve changed to a shorter, lighter, less bulky and more versatile tool. I call it “crevasse cord”.

It's 10ish feet / 3.5 m of V-TX cord, made by Sterling Rope. V-TX is impressive. It's just 5.4 mm and rated to 15 kN. It has a low stretch Dyneema core and a polyester sheath. It's fairly supple, which means it’s good for friction hitches. I carry it “open” or untied, not permanently tied in a loop with a welded double fisherman’s knot.

It's relatively inexpensive, about $1.20 per foot at my local climb shop.

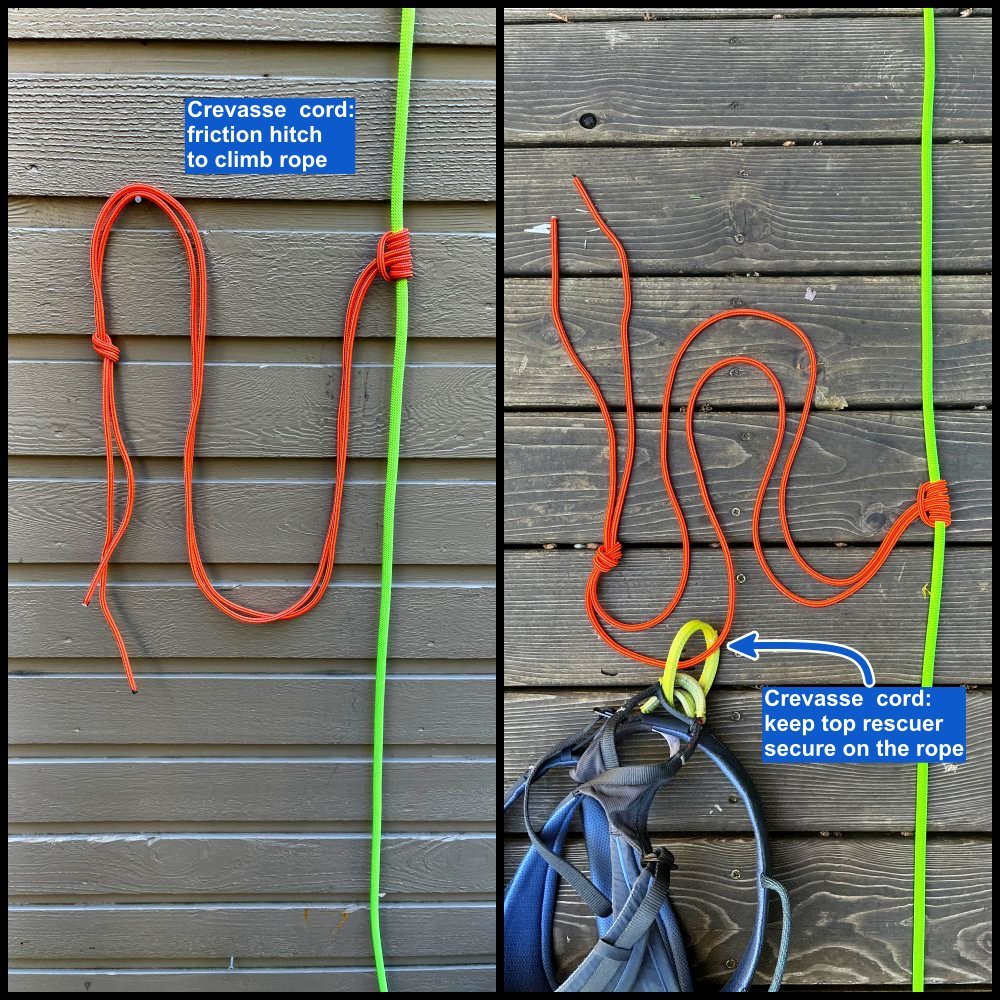

Using a crevasse cord - friction hitch

As a friction hitch - Tie any friction hitch around the rope, usually a prusik or Klemheist. If you need a shorten the connection, tie an overhand knot.

Left photo: If you’re the unfortunate person in the hole, you can tie a friction hitch and use this as a foot loop to ascend the rope. (Please, stop carrying those old-school designated “foot prusiks”.)

Right photo: As a rescuer on top, you can use this as your primary connection to the anchored rope. Connect yourself to the hitch by passing the cord through your belay loop and tie an overhand knot. Cool, you’re now connected to the friction hitch and you saved a carabiner.

Using a crevasse cord - single point anchor building

If you build a T slot (aka deadman) anchor, you need at least about 4 feet or 1.5 m of sling or cord to connect the anchor to your master point. The crevasse cord is perfect. You can basket hitch the cord through a hole of a picket, or clove hitch it around a deadman such as an ice axe.

Electromagnetic interference (EMI) and avy transceivers, from BD

Black Diamond published a very interesting study about the effects of common electronic devices and how they generally do not play well with avalanche transceivers. Here’s a link to their excellent article.

In January 2024, Black Diamond published an interesting study about how different electronic devices that we might carry in the mountains affect avalanche transceivers.

It's definitely worth a read. From their blog post:

“Various electronics often found in the backcountry were used in our test, including smart watches, GPS watches, smartphones, two-way radios, action cameras, satellite communication devices, electronic airbag packs, and even a snowmobile. The searching transceiver was held at 50cm from the torso using a static tether to help maintain the appropriate distance. Each item was then placed in a normal use position as noted below.

The goal was to determine how bad it might be to violate the 20/50 rule. To do so, many items were held closer than 50cm (i.e., heated gloves and smart watches). Each item was tested three times, and the average taken. We then calculated the reduction in range compared to a baseline with no other items present.”

“The takeaway here is that EMI is real, and it can have a significant impact on transceiver performance! And we can’t stress enough the importance of updating the firmware of your avalanche transceivers and electronic avalanche airbag packs.”

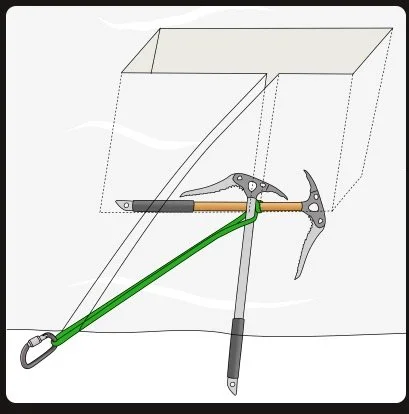

A strong, simple and fast snow anchor

The T slot (aka deadman) anchor is usually a good choice when building a crevasse rescue anchor in snow. Here’s a quick enhancement that can double the strength.

Disclaimer: There is WIDE variability in the strength of snow anchors, due to factors like depth of the anchor, what you’re using for the deadman, temperature and water content of the snow, whether you stomp down (aka work harden) the snow between the anchor and the load, etc. A certain snow anchor flavor that tests to a certain strength in one location does not mean that result applies everywhere.

If you carry a picket, you have various options for building a snow anchor. With a very hard snow you can maybe use a vertical picket top clipped. With medium to hard snow, a vertical mid clip picket can work.

However, with softer snow, or if you choose not to carry a picket, about your only option is the “T slot” (aka deadman) anchor. This anchor can be made with gear like an buried ice axe, skis, or a backpack.

Here’s a way to (maybe?) double the strength of the T slot anchor, with a few seconds of work and one additional piece of gear: Add a vertical reinforcing placement to the horizontal placement.

image (used with permission) : https://www.vdiffclimbing.com/glacier-travel-snow-anchors/

This does a couple of good things:

It makes the horizontal placement much harder to pull out.

If the horizontal placement, like an ice axe, shifts a little bit under load, it can prevent the clove hitch (that's on the horizontal axe) from slipping.

(If you use a picket and girth hitch the middle hole for the horizontal piece, you don't have to worry about the connection point slipping.)

The typical method to beef up a snow anchor is to build an entirely separate one, and try to connect / equalize them with cord. This is certainly effective, but it can take a lot more time and gear (more cord and carabiners) to build, and will probably end up pretty much the same strength as this one.

Sounds good. How strong is it?

My pal Ryan Jenks at HowNOT2.com tested this. He got about 8 kN, which is pretty impressive! Compare this to a single horizontal buried picket, which he tested at about 4 kN.

Adding the vertical picket to reinforce the horizontal one pretty much doubled the strength of the anchor, at least in this one test.

Keep in mind this was in high water content snow in the Washington Cascades. This usually conpacts very well and make some reasonably strong anchors. Your mileage may vary.

Keep in mind that a typical crevasse rescue anchor will only need to hold less than the weight of the victim when they’re hanging. (The friction of the rope passing through the snow reduces the load on the anchor.) When hauling with a 2:1, if the pull strand is not redirected, the anchor should see about 2–3 kN at most. So, in the typical crevasse rescue scenario, loads on the anchor usually are fairly low which is a good thing.

I’ve seen quite a few studies of the strength of horizontal deadman anchors, but this is the only one that adds the vertical element. If anyone knows of other studies, please email me; I’d like to add those to this article.

A few snow anchor testing resources . . .

Here's a link to the British mountain rescue magazine from (I think) 2018. They got results that were different. Like I said, your mileage may vary.

If you really want to nerd out on snow anchors, here’s a webpage that summarizes most of the publicly available studies.

HowNOT2 video showing snow anchor pull test results. Horizontal picket about 6:00. Reinforced horizontal picket, about 6:35.

Screen grab from the above video, setting up the reinforced picket.

Finally, for a very deep dive into snow anchors, here is a nice presentation from the Mountain Rescue Association featuring snow anchor expert Art Fortini.

Grivel Clepsydra S - the best carabiner for glacier travel?

For glacier travel, it's usually best practice to clip, not tie, to the rope. The Grivel Clepsydra carabiner just might be the best tool for the job: the twin gates will never freeze or jangle open, and the keeper gate prevents cross loading. Plus, it has a bonus feature as part of a minimalist hauling system.

The Grivel Clepsydra is a very unique carabiner. It has a few features that make it perfect as your clip-in for glacier travel. (It comes in two sizes; here I’m featuring the small (S).)

Why is the Clepsydra S great for glacier travel?

No chance of cross loading means you only need one carabiner to clip to the rope

Unique Grivel twin gate means it’s always secure, can’t freeze shut, and can’t wiggle open during a day of glacier tromping. (Yes, the twin gate takes a little getting used to, but you'll figure it out.)

You can use the small end as a prusik-tender in a hauling system (photo below)

Small, fairly lightweight

When you’re not glacier climbing, it works perfectly with a Grigri, as the little “horn” prevents the carabiner from being cross loaded

The standard recommendation for clipping to the rope for glacier travel is to have two opposite and opposed carabiners, at least one of them locking. With the Clepsydra, you only need one.

Before I got this carabiner, I used the Black Diamond Gridlock. This works pretty well, but the screwgate can loosen up over a day, plus as an HMS carabiner, it’s larger than necessary.

Here's how to use the Clepsydra as a “prusik minder” in a hauling system. The small end of the Clepsydra keeps the prusik hitch from being pulled through.