Friction can lower forces on an anchor

This tip comes from my pal and canyoning expert Kevin Clark and his book, “Canyoning in the Pacific Northwest: A Technical Resource.”

I did a live body test of this at the rock climbing wall in Marymoor park in the Seattle area. My friend Ryan from @hownottohighline shot the video. See the short Instagram reel and the results here.

Results:

me hanging fully on rope: 190 lbs on anchor

Rope angle from edge to anchor about 50°: 135 lbs on anchor, or about 30% less load

Rope angle from edge to anchor about 10°: 80 lbs on anchor, or about 58% less load

When rappelling, the maximum force on the anchor usually occurs just as the rappeller is passing over the edge on top of the pitch. Once below the edge, the load on the anchor is reduced by the friction from the rope passing over the edge. The more contact with rock the rope has, and the larger the angle, the lower the force on the anchor.

There are lots of factors involved, such as how slippery the sheath of your rope is, if the rock edge is rounded or sharp, whether the rock is wet or dry, the type of rock, etc.

With a rope that runs over the edge at a 45° angle, the load on the anchor can be reduced by as much as 50%.

If the rope passes over the edge at a 90° angle, the load reduction can be as high as 66%.

If your anchor is questionable, that's probably a good thing. The trade-off is your rope is going to be harder to pull.

Let's look at some examples. Let's assume our rappeler weighs about 100 kg.

Example 1: The rope is anchored to bolts hanging over the edge of the cliff top. There is zero friction from the cliff edge. Our 100 kg rappeler puts a 100 kg load on the anchor. Hopefully that should be pretty obvious. (And yes, starting your rappel from a position like this might be a bit difficult.)

Example 2: Instead of using the bolts, the climber is now rappelling from a sling they put around the tree about, say, head height. Yes, this can increase leverage on the tree, but if the tree is stout, it doesn't really matter. A higher anchor point is more convenient to get rigged and start your rappel.

(Sidenote, it's best practice to avoid rapping with your rope around the tree. Doing this can damage the tree, get tree sap on your rub, and make for a very difficult pull. Add a sling instead.)

This makes an angle of about 45° over the edge of the cliff. Once the climber is over the edge, how much force do we now have on the anchor?

Using that best case scenario of 50% force reduction, the load on the anchor is now about 50 kg.

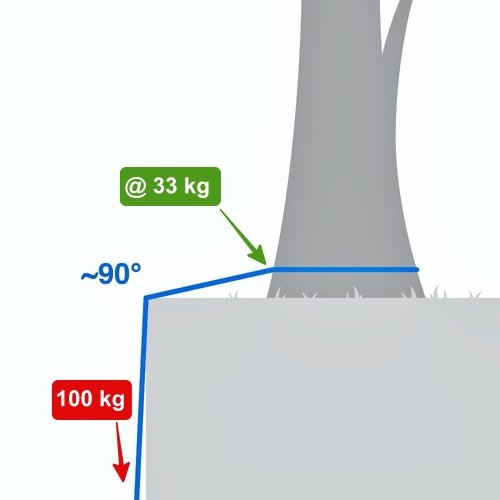

Example 3: Instead of anchoring higher up in the tree, our climber decides to use the base of the tree. (This decreases the leverage on the tree, but might make it harder to rig your rappel.)

This makes an angle over the cliff edge of around 90°. Once the climber is over the edge, what kind of load do we now have on the anchor?

Assuming a best case reduction of about 66%, the tree only sees a load of 33 kg. Good trick if your tree (or other any other sort of anchor) is marginal!

Here are some other techniques to minimize the load on the anchor:

Interestingly enough, you can significantly increase the forces on the anchor in that brief second or two when your feet are on the edge of the rock and you are leaning backwards. This has an interesting force multiplier, even if it's just for a moment. If your anchor is marginal, you probably want to avoid doing that.

To counter this, you can get as low as you can when starting the rappel, perhaps even sliding over the edge. Canyoneers call this a "soft start.”

Pushing the rope down into the rock surface as you go over the edge to help maximize friction.

Keep a consistent load on the anchor, good rappel technique, etc. Don’t jump down the rock like a special forces cowboy.

Use footholds if possible to keep load off the anchor.