Alpine Tips

Try a static rope for glacier travel

Are you climbing on a moderate glacier, such as a standard route on many Pacific NW volcanoes, without any actual lead climbing? Consider a static rope.

Are you climbing a low to moderately angled glacier? You need a rope for crevasse rescue only, but not for catching any real leader falls, and you don’t want to carry any more weight or length than you have to.

Consider a static rope. If your only purpose of the rope is for crevasse rescue, then you don’t need the dynamic qualities of a typical lead climbing rope. In fact, the extra stretch in a dynamic rope (especially the skinny ones) will result in a longer fall and will add unwanted stretch to any raising system you may need to build. Conversely, the static rope can give a harder yank on the people up top if the rope management is a little sloppy, with extra slack, so keep that in mind.

These ropes can be up to 40% lighter than a similar length of 8 mm dynamic half rope, typically used in glacier travel by many climbers. (Approx 25 grams per meter compared to about 40 grams per meter.)

Of course, you need to take some measures to add extra friction when rappelling, such as using a device designed for skinny ropes such as the ATC Alpine Guide, adding two carabiners to your belay loop, or maybe even putting both strands of the rappel rope through the SAME hole in your rappel device. As always, practice with these in a controlled environment before you have to do it for real on the mountain.

Several companies offer dry treated, small diameter, ultralight static ropes specifically designed for crevasse rescue.

The Petzl RAD system, an complete kit designed specifically for crevasse rescue, uses very low stretch 6mm static rope. (“RAD” stands for “Rescue And Descent”, for you acronym people.)

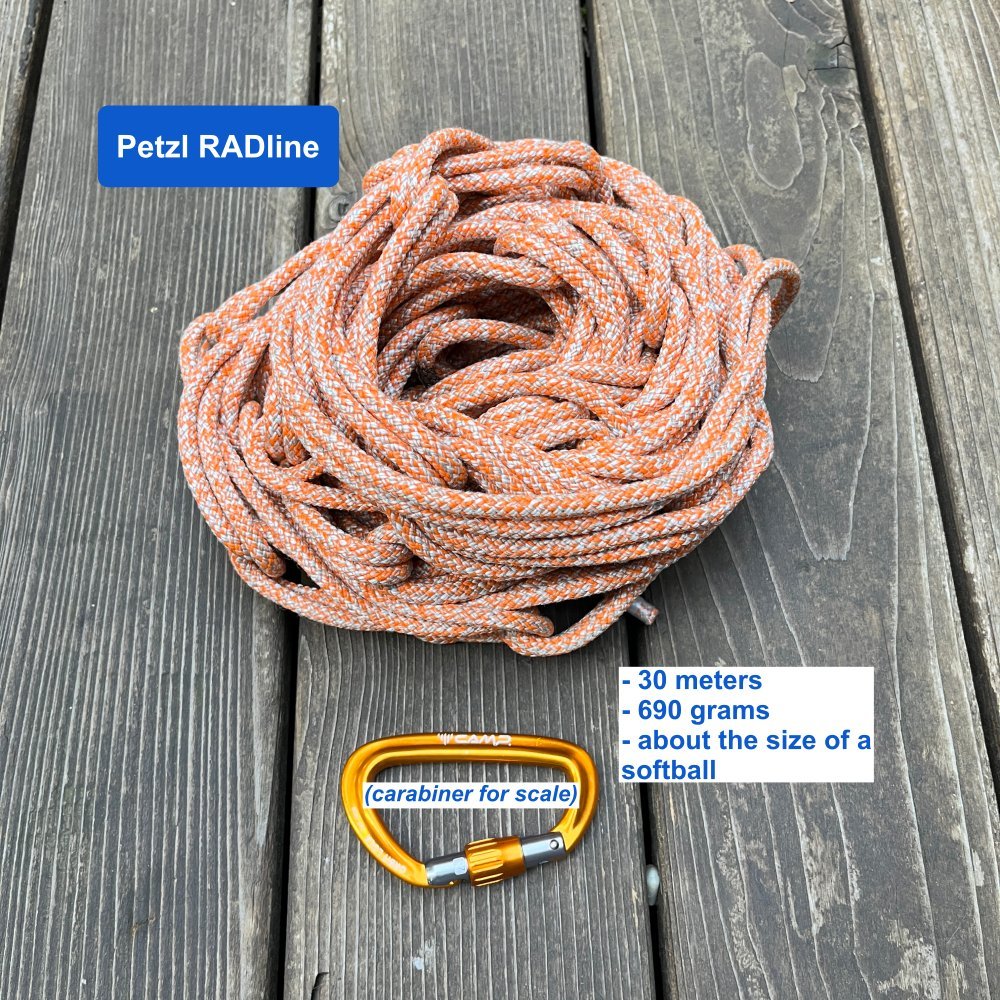

The Petzl RADline can be purchased separate from the above mentioned system. I have a long article about this rope, read it here.

Mammut makes a 6mm dry treated Glacier Cord, also a static rope designed for crevasse rescue. This rope has a middle mark and comes with a nice storage bag, which can be used for a clean toss when you need to rappel.

These ropes (usually) play nicely with tiny ascenders and progress capturing pulleys, such as the Petzl Tibloc, Petzl Micro Traxion and the Edelrid Spoc, tools which can simplify the crevasse rescue process.

These specialized ropes typically have a Dyneema core, giving them minimal stretch, light weight, and nice strength, typically about 14 kN. Another benefit is that they absorbs basically zero water, making them lightweight when dragging through snow.

Be careful with your friction knots. You may need use triple wrap prusiks made from skinny 5 mm cord to be sure your friction knots hold on the narrow diameter line.

Read some great gear reviews for these ropes, and a lot more gear, at Black Sheep Adventure Sports.

Here's a quote on this topic from “The Mountain Guide Manual” by Marc Chauvin and Rob Coppolillo (pg 243):

“Because of all the dynamic aspects to a crevasse fall - climbers sliding on the snow surface and the rope and bending over and cutting into the lip - it is becoming acceptable to use static rope.

In fact, Petzl has conducted tests that suggested the spring/rebound nature of a dynamic rope actually makes it more difficult to stop a fall.” If you want to get into the test results, here’s a link to the Petzel website which discusses them.

Here’s a bit of Youtube chat about the topic with another pro guide:

This tip is mentioned "The Mountain Guide Manual" by Marc Chauvin and Rob Coppolillo, and "The Mountaineering Handbook" by Craig Connally.

(This is not an affiliate marketing link, I am offering you these links as a convenience to you and because these books are great.)

How to always have dry socks with only two pairs

Dry Feet = Happy Feet! You can always have dry socks, even on multi day snow climbs, if you follow this tip.

On longer Pacific Northwest snow climbs such as Mt. Shasta and Mt. Rainier, (not to mention longer expeditions) keeping your feet in good shape can be a challenge. Even with modern boots, your socks and feet will get progressively more wet if you don’t take proactive steps to dry them.

Here’s a tip to have dry socks every day on milti-day snow climbs, while bringing only two pairs.

Wear a pair of socks (pair 1), get them wet.

Hang pair 1 up in the tent that night and all next day.

In the morning, put on pair 2.

That night, hang pair 2, and put pair 1 in the sleeping bag with you, and put a hot water bottle inside each sock (preferred), or put the socks on your belly. (This is a perfect use for a 20 oz. Gatorade bottle, a great water container we talk about in this Tip.)

Repeat indefinitely.

Bring two shirts for sweaty approach hikes

Headed on a snow climb that has a long approach followed by more technical climbing? Don’t “sweat” the approach - bring an extra base layer and swap it as you slow down.

You’re heading up Mt. Hood to try Leuthold Couloir in March. Your team is setting a good pace on the approach, and you’re sweating a fair bit, even after you strip down to your base layers and open a few zippers.

At Illumination Saddle where you stop for a break and to rope up, you are suddenly chilled by the wind that often appears at passes, even though you’ve put on your puffy belay jacket and hat. That damp first layer seems to suck the warmth right out of you.

Solution: Bring two shirts, one lightweight and one mid-heavyweight. Tackle the fast-paced approach hike in a lighter shirt. When you start the technical climbing (or arrive at base camp) which usually means moving more slowly, remove the sweaty shirt and replace it with a dry, thicker synthetic top.

The few seconds of discomfort from exposing your upper body to the elements are outweighed by the immediate warmth, comfort and psychological boost that comes from a fresh, warm shirt. If you take the rest of the climb at a more modest pace, the second shirt should stay dry.

3 tips for better running snow belays

Running belays on snow can be a lower risk and relatively fast way for a rope team to travel in steeper terrain. Here are three tips to make them more effective.

image: Climbing.com

General caution on running belays: Snow anchors are probably not as strong as you think they are. If things are getting steep and you think there's a chance of a fall putting significant impact on the picket, it's probably best to start climbing with belayed pitches, have your most skilled person climb a rope length and fix the rope, or perhaps turn around.

Having said that, there are some times when using a running belay is appropriate. Here's how to make the best of it.

1 - The Better Way to rack pickets

Many climbers don't give a great deal of thought how to rack pickets, usually just slinging them over their neck. Doing this is just about guaranteed to dangle, tangle, and strangle, and if you're doing a long running belay with more than about three, it gets even worse. This applies to the leader as well as the cleaner.

A much better method is to clip a carabiner through the third hole of the picket, and carry the pickets on your vertically clipped to your harness or pack shoulder straps. Here’s a separate post that describes how to do it, with some pictures.

The leader can carry pickets on their backpack quiver style, but you need to set them up in a way so they can't fall out.

2 - Consider a whistle

Running belays require clear communication between the entire climb team, to tell the leader to stop and place more pro, or for the team to stop while the last person cleans.

If it’s windy, the route goes around a corner, you have your hood cinched down tight, you’re wearing a windproof fleece hat, your ice tools are knocking off chunks of ice and snow, you’re mentally focused on a tough lead . . . or all of the above, it can be very hard to hear the calls for “pro” or “cleaning”. Consider whistle blasts to signal the leader to stop and place more gear. Wear the whistle on a short cord girth hitched to your pack strap and be sure you can get to it with gloves on and using one hand.

The leader doesn’t need to have this, but all of the following climbers should consider it.

3 - Running belays - Max party size is three

A simple rule of thumb for running belays is this - keep the party size to 2 or 3 people max on a rope. With more than 3 people, it’s almost always faster to fix the rope and have the everyone come up on a fixed line or simulclimb.

Reason: if the team always keeps one piece of pro between team members, with four people on the rope, the leader has to carry and place a LOT of gear!

Ice axe + trekking pole for moderate snow ascents

Don’t ditch your poles when the going gets steeper and snowy. Having a pole and ice axe can be a great combo, especially when traversing.

Many climbers use trekking poles, but restrict their use to the approach trail or low angle snow. When the terrain gets steeper, most people put both poles in the pack and use only their ice axe. On moderate snow ascents, try using one pole in combination with your ice axe. Keep your axe in your uphill hand, and the extended pole on the downhill side. This is especially nice on traverses.

This technique has two benefits: One, you create a lot of additional stability with the downhill pole, adding greatly to balance and confidence. Second, once you get into the rhythm, you can lean a bit on the downhill pole and use some arm muscle to push uphill, taking some weight off your legs. Take some load off your legs, feel a lot more in balance, and climb faster - what’s not to like?

Here’s a photo of a climber traversing a moderate snow of about 35 degrees on the lower approach to the Cathedral Ridge route on the northwest side of Mt. Hood. Note the pole in the downhill hand, axe on lanyard in her uphill hand. She walks quickly, in balance, and the pole is there to keep her that way.

If you need any more evidence, here’s a photo of Ed Viesturs on the summit of Nanga Parbat, showing him with an axe in one hand and . . . you guessed it, a trekking pole in the other.

Glove tip - always bring 2 pair

Good rule of thumb for snow climbing: always bring two pairs of gloves at a minimum. They don't need to be name brand, especially your back up pair. Here's how to find some online.

While we all have wide range of cold tolerance for our hands, I consider at least two pairs of gloves for snow climbs mandatory. (Read the classic book “Annapurna” for some epic frostbite tales, if you need convincing.) If you ever drop a glove on a cold route and don’t have a spare (or at least an extra sock) you could be in serious trouble.

The gloves I bring on pretty much every trip are Showa Temres 282-02. They are inexpensive, waterproof, extremely warm, and work great. Here's a detailed article about these terrific gloves.

The second pair? Of course, the temperatures where you're climbing dictates your glove choices. In moderate conditions, a light windstopper or Powerstretch fleece may do the job.

For technical climbing in really cold conditions, many climbers bring three or four pairs of gloves.

The backups sure don't have to be name brand glove$ from the $pendy mountaineering $hop. Try an Amazon search for “cycling gloves”. Here’s a pair I got for road biking that do fine as a backup for climbing - stout fabric, windproof, and have touchscreen capable fingers. And, how can you go wrong for about $12?

How to make bomber tent anchors in snow

There's no such thing as a freestanding tent on a windy mountain. Here's a light weight and nearly free way to make solid snow anchors for your tent.

I was about 30 minutes outside of Camp Muir on Mt. Rainier, turning back after a storm-induced retreat. Just as I caught a view below me of the tent city, a giant gust of wind smashed into the camp, lifted several tents into the air, and cartwheeled them thousands of feet down the glacier and out of sight. Whoops! Fortunately, it wasn't mine, but lesson definitely learned!

If you’re setting up a tent in the snow, you need a good way to anchor it down. (There’s no such thing as a freestanding tent in a windy place.) Buried trekking poles, sticks (maybe collected on your approach hike), skis and rocks work well, as do some sort of a buried deadman. A picket is bomber, but you’ll probably need them for your climb.

Here’s a great choice: 1 gallon ziplock freezer bags. Reinforce the lower sides with duct tape, fill about 2/3 with snow, and seal. Then tie the tent cord around the middle making it into an hourglass-like shape, then bury it. For knots, use a tautline hitch or a trucker’s hitch to fine tune the tension on the tent cord. (See another tip of the week for how to tie these very useful knots!)

So, how strong are they? Answer, more than you think. A study by the French National Guide School conducted some pull testing on various types of deadman snow anchors, and they found that a buried plastic bag could hold a load of approximately 200 kg!

One more option: If you anticipate high winds but no precipitation, you can remove the some all of the tent poles when you leave camp, lie the tent flat, and put some rocks gently on top of it.

Don’t let this happen to you!

image: https://manonice.com/2014/10/

Glissading - not always your best option for descent

Glissading - You might have learned how to do it on your first day of climbing school. It can be fun, save time, and your quads muscles in certain ideal situation. But there are also a lot of reasons why you may want to avoid it.

Glissading, the skill of (mostly) controlled sliding down a snow slope either sitting or standing, can be a lot of fun and save you time and legs on the proper slope. Pacific NW routes where this can work well include Mt. Hood south side, Mt. Adams south side, the Muir snowfield on Mt. Rainier, and various routes on Mt. Shasta.

Beginning climbers often learn this technique on day 1 of snow school, and then mistakenly think that it's something to be done at every opportunity. (And, hopefully you learned this on day 1 of snow school as well, but it's worth repeating: never glissade with crampons on!)

However, glissading has some serious downsides, and saving a few minutes on the descent may not always be worth it. Before you glissade, consider these points:

Much greater chance of injury than simply walking (usually a broken/sprained ankle, going too fast and cratering into a rock, talus or scree, or dropping into an unseen crevasse)

You wear out your gear faster (seat of your pants and pack bottom)

You get your butt wet

You can lose gear strapped to the outside of your pack, like trekking poles and crampons unless it’s very well tied down

Questionable time savings – saving 20 minutes on a descent by glissading may not mean so much when you weigh it against the downsides mentioned above, and the fact that a round trip climb may take 8-10-12+ hours.