Alpine Tips

My crevasse rescue gear

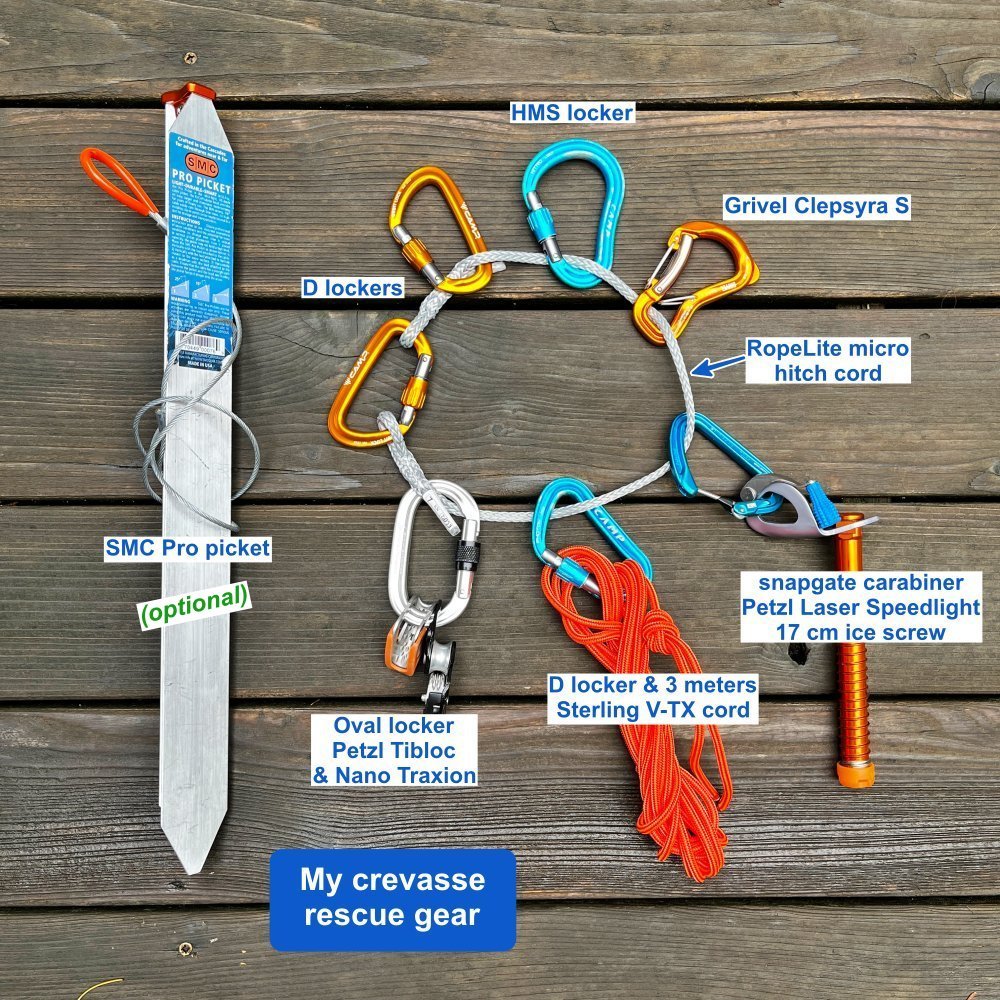

There are many approaches to crevasse rescue and many choices for what gear to bring. You need light weight, multifunction, and hopefully have teammates with similar kit to have an effective rescue. Here's my go-to crevasse rescue gear.

There are many different approaches to crevasse rescue, and a near infinite combination of gear that you could carry. The basic requirements are 1) being able to climb the rope if you fall in, and 2) rescuing your partner if you’re the lucky one on top, and they can’t climb out. Fortunately, modern tools and techniques lets you do both with a minimum of gear and weight.

The gear requirements can change depending on team size and general skill level, but here’s a pretty good starting point.

This is pretty much the bare minimum. The idea is with a three of four person team, if everyone carries more or less the same basic kit, rescuers can combine gear as needed.

If you're on a two person team (which is generally considered experts only) you might want to carry a few more items, like maybe another locker, or a120 cm sling.

My crevasse rescue gear

6 locking carabiners: Grivel Clepsydra S, Black Diamond oval, large HMS and three “D” - The Clepsydra works great to clip yourself to the rope, because you can never crossload it, and the gate is very secure. Also works as a progress capture with a a prusik, if you don't have any progress capture pulley like a Traxion. The oval locking carabiner is a time-tested workhorse, and plays well with devices like the Traxion and Tibloc. A larger HMS locking carabiner is helpful if you need to clip other things to it. Finally the D lockers covers any other secure connection you might need. (Yes, I probably have one more locker than I need, but Murphy's Law of rescues is you always need one more locking carabiner.)

1 small snapgate carabiner - you need to rack your screw on something. You can use a non-locking carabiner for non-critical connections, such as the “tractor” in a 3:1 Z drag.

Petzl Tibloc - handy and lightweight ascender and rope grab.

Petzl Nano Traxion (or Micro Traxion) - the modern standard for crevasse rescue gear. Yes, they are expensive, but so helpful in so many situations, they are pretty much becoming everyday carry.

17 cm aluminum Petzl Laser Speed Light ice screw - if you can get down to ice, this can be your anchor on the top. If you fall in, you might be able to place the screw and clip yourself to it to take your weight off of the rope, which can make life for your partners on top a LOT easier when they set up the rescue. Don't bring a screw shorter than about 16 cm.

About 3 meters of Sterling V-TX cord - typically used for equalizing a second anchor, ascending a rope, or securing yourself to the rope system. (Amazing cord; 5.4 mm and rated 15 kN). You don’t need the standard (7 mm 6 meters long) cordelette on a glacier.

Short friction hitch - for climbing up the rope if you fall in, and for making a “tractor” on your hauling system. Here I’m using a spliced eye 5mm hitch cord, which grips well on 6 mm rope. This is made by a cool company called RopeLite; check ‘em out for custom spliced ropework solutions. (There are many other options, such as a loop of 6mm cord or a Sterling Hollowblock.)

What about that picket? Pickets can be very helpful in building a snow anchor but they're not required. Pickets are commonly carried in North America, South America and New Zealand, but not so much in Europe. A more minimalist approach involves making a T-slot anchor with your buried ice axe, skis, or backpack. But to me the axe is a crucial piece of gear, and I'm not too excited to bury it in the snow in case I need it for something else.

When I do carry one, it's the SMC Pro Picket. This is reasonably lightweight, has a pointy end for going into the snow and a reinforced top for bashing on with a hammer. The nicest feature is a permanently attached metal cable on the middle hole, which is how pickets have maximum strength in either vertical or horizontal placements. (That means you need one less 120 cm sling.)

What I don’t bring: pulley, belay device, several “just in case” extra carabiners, designated waist or leg prusik loops. Need another pulley? Grab the Traxion from your partner. Need to rappel or give someone a belay? Use a Munter hitch on your HMS carabiner. The carabiners above are more than enough. And forget those old-school designated waist and leg prusiks; you can easily ascend a rope with the gear shown above.

Where to carry this gear? You want the gear you need to climb a rope easily accessible on your harness or pack gear loops, not inside your pack. For ascending a rope with the gear shown here, I’d keep the orange cord and the oval carabiner with the Tibloc and the Traxion on my harness at a minimum. The rest can probably go inside your pack. I’d also keep the screw on my harness. If you fall in, you might be able to place it and clip to it, removing your weight from the rope as mentioned above.

Harness: A minimalist mountaineering harness, I like the Petzl Tour. Leave that sport climbing harness with the five gear loops at home. You want lightweight, no padding because you have on lots of clothes and (hopefully) are not gonna be hanging in it, with leg loops that open so you can easily put it on while wearing crampons or skis.

Rope: Varies on team size and skill level. Good options include:

30 meter, 6 mm Petzl RADline

40 meter, 7.7 mm Sterling Dyad

50 meter, 7.1 mm Edelrid Skimmer (which is currently the lightest dynamic rope on the market)

The diameter, length, and static vs. dynamic issue of the “best” rope for glacier travel is a BIG topic. Here's a link to some articles on my website that take a closer look. 1) Petzl 6mm static RADLine, 2) static rope for glacier travel.

So, that's my kit. Simple, lightweight, everything has a function. With this I can build just about any flavor of mechanical advantage hauling system I might need, like a 2:1, 3:1, and 6:1.

Some examples of 6:1 systems are here.

Minus the picket, this is what everything weighs.

Rigging your rope for glacier travel

Here's a fast, clever and easy-to-remember way to ensure proper spacing between team members when traveling on a glacier. Plus, a diagram and photo to show actual distances for three and four person teams.

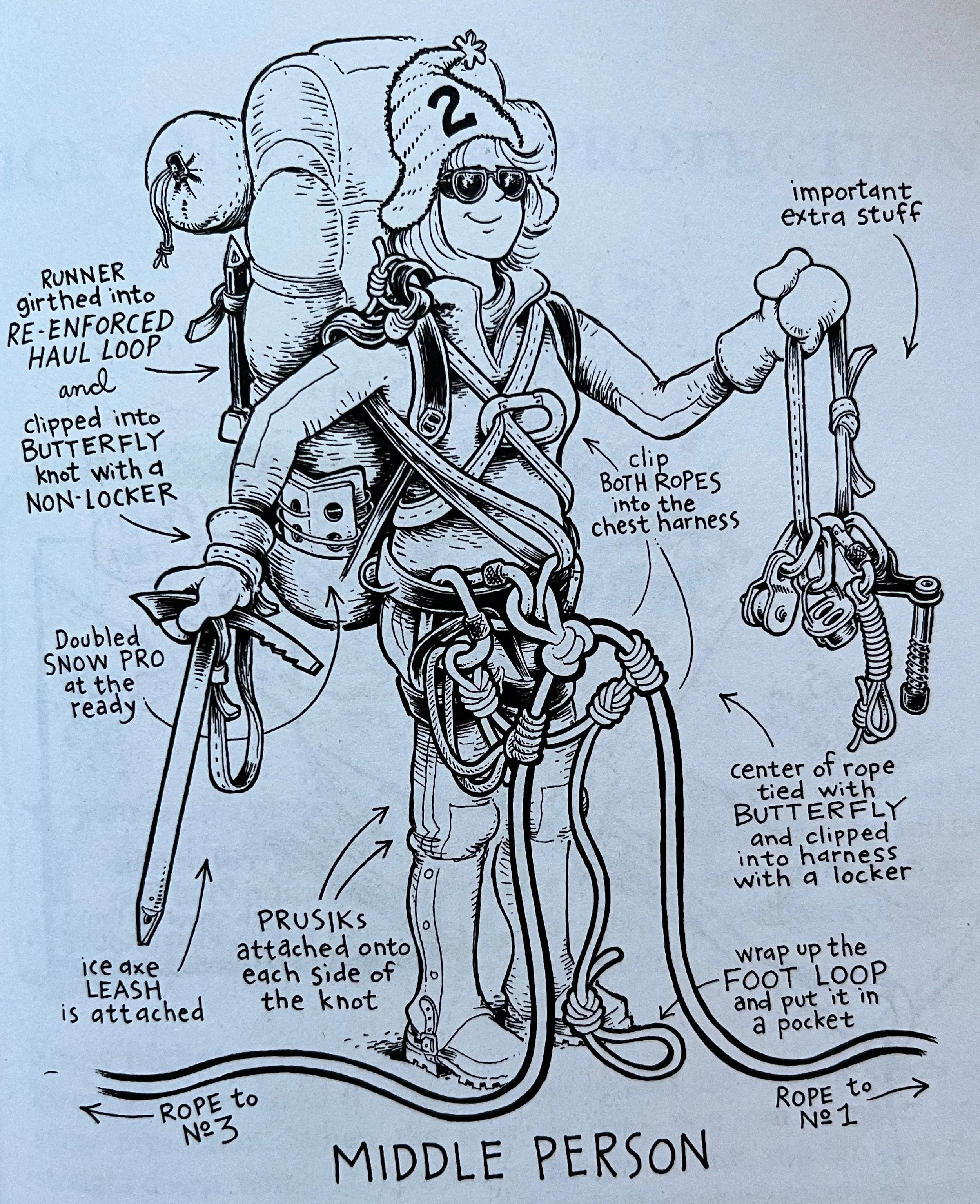

Image: from the highly recommended and hilarious book, “The Illustrated Guide to Glacier Travel and Crevasse Rescue, by Andy Tyson and Mike Clelland. Anyone setting foot on a glacier would do well to get this book. The method shown is a bit outdated, but it's still a great drawing!

(There are a few different book editions with different covers. They're all good, get whichever one you can.)

credit: Mike Clelland

I remember when I first learned crevasse rescue WayBackWhen, it was pretty darn simple. Two people tie to each end, one person ties to the middle, and off you go! 50 meter rope, 25 meters between everybody.

Turns out that has a few problems:

Communication can be difficult because people are further apart.

All the extra rope gets hung up on ice blobs and snow-sickles.

How do you do a rescue if the middle person falls in?

Happily we’ve moved into the modern era, where you climb a bit closer together (at least in my neighborhood, the Pacific Northwest), and the end people carry extra rope to initiate a rescue. But, that still leaves a few questions:

What distance should you have between climbers?

It sort of depends on the potential size of the crevasses you may be facing, but for moderate sized crevasses typical of the Pacific NW, here’s a quick and easy to remember how to set up the rope spacing. It varies a little bit, depending on the size of your team.

Take the number of people on your rope team, and subtract that from 10. That gives you the number of double “arm spans” between climbers.

2 climbers: 10-2 = 8 - 8 arm spans of rope between climbers (need to leave a few extra meters to tie brake knots . . .)

3 climbers: 10-3 = 7 - 7 arm spans of rope between climbers

4 climbers: 10-4 = 6 - 6 arm spans of rope between climbers

Notes . . .

This is known in some circles as the “10 minus equation.”

If you’re on a two person team, it’s best practice to tie 4-5 brake knots in the rope between each climber. It's optional for 3 and 4 person teams, but if the terrain is hairy then go ahead and tie some.

Generally, you want to put the least experienced person(s) in the middle, and the two more experienced/skilled people on the end. The end people will be more responsible for route finding and probably initiating a rescue if you need one.

Note - there are lots of different ways to rig your rope team for glacier travel. This is one of many that works. In areas with larger crevasses, like Alaska and the Himalaya, you’d probably want more distance between people than what I’m describing here.

Pro tip: If you're doing an alpine start, rig your your rope with knots and coils the night before. It's one less thing to do at 0:dark:30 by headlamp when you're sleepy.

Generally, it's best practice to have all team members clip to a knot with a locking carabiner, rather than tying the rope through the harness. Doing this allows you to unclip from the rope more easily, which is convenient when performing a rescue.

The end people need a good way to secure the extra rope. Some people advocate stuffing it in your pack. Bad idea, because every time you want to get in and out of your pack you have lots of annoying rope coils. Much better is to secure the rope in a small butterfly coil, I like to secure the coil with a Voile ski strap. Yes, I know how to tie off a butterfly coil, but using a ski strap is faster and easier. I don’t like the coils around my neck unless there’s a good reason to do so, like moving from glacier to rock, where you need to take in coils and walk close together.

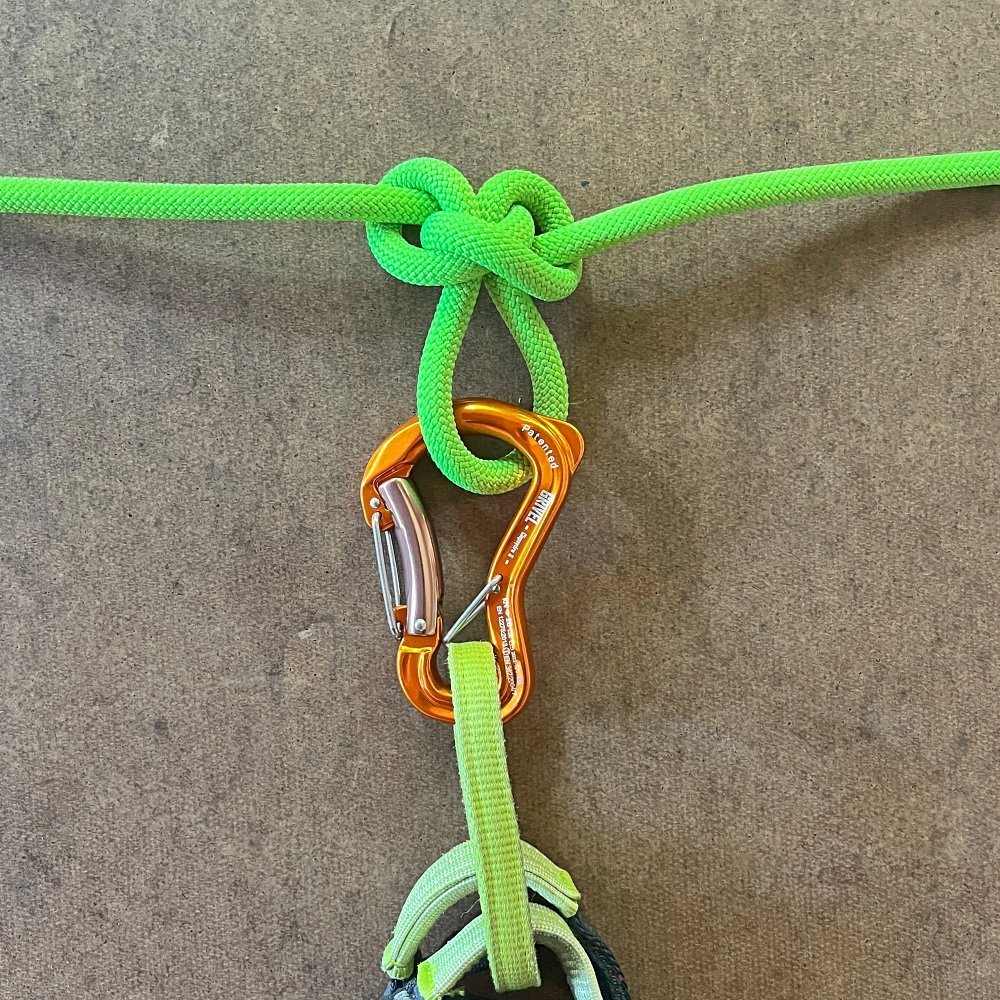

The standard approach to clipping to the rope is to use two carabiners, opposite and opposed usually with at least one a locker. Here's my alternative, using the odd-looking Grivel Clepsydra S carabiner. It has a wire clippy thing so it can never be cross loaded, and it has a double gate that will never freeze shut or wiggle open during a day of tromping around on the glacier. It's my new favorite.

A team of two can require a longer rope (60 meter minimum) than a team of three or even four.

Yes, this is a little counterintuitive! If you're using the modern standard of a drop loop C, that means you need about twice the distance between climbers at a minimum for a typical rescue. A party of three or four will ideally build an anchor at the closest team member to the fallen person. This allows them to use the rope between the other team members for the drop loop and thus they can carry fewer rescue coils on each end. A team of two is probably not able to do this.

This means that it's best practice for a two person team to be on a 60 meter rope at a minimum, while a three person or four person team can probably use a 50 meter rope.

Check out the below diagram for a two person team. With 8 arms spans between climbers, and with 4 brake knots which each take about 1 meter, that leaves just 15 meters in rescue coils for each person to carry.

The good news is, if your drop loop turns out to be a little bit short, it's easy to extend it with whatever extra slings, cordelettes, etc. you might have available. This means that a two person team does NOT always need to carry twice the amount of rope between climbers. (Another alternative for a two person team with a shorter rope is that they do not use a drop C and instead use a drop end 3:1, which comes with its own set of problems and benefits. Here's a detailed article on this technique.

Either way, the bigger picture, if you’re a two person team in serious crevasse terrain, you absolutely have to have your systems dialed and be completely self-sufficient to perform a rescue. Two person glacier travel is recommended for experts only.

Rope rigging for a THREE person team (with at least two experienced climbers):

Find the middle of the rope, tie a butterfly knot for the middle person.

Measure about seven full arm spans from this middle knot towards one end, and tie a butterfly knot. Repeat for the other half of the rope. These are the clip in points for the two end people. The end people coil the remaining rope for use in a possible rescue.

If you have only one experienced person on your rope team, then the novices should probably clip in starting at one end of the rope with seven arm spans between them, and the more experienced person should carry all the the remaining rope. Let’s hope the guide doesn’t fall in . . .

Rope rigging for a FOUR person team:

Find the middle of the rope.

Measure three arm spans to the right of the rope middle, and tie a butterfly knot.

Measure three arm spans to the left of the rope middle, and tie another butterfly knot.

Finally, measure six arm spans from each of these knots toward end of the rope, and tie your final two butterfly knots for the end climbers. Again, the two end climbers should ideally be more experienced people capable of route finding and crevasse rescue. They also carry the remaining rope, either coiled over their shoulder or stuffed into a backpack.

Distance wise, this works out to be about 10 meters between climbers.

(Note the orange Voile ski strap securing the coils for the climber on the right, a quick and secure way to tame extra rope.)

Check out the nice video from AMGA Guide Jeff Ward to see how this works.

Printing backcountry maps in CalTopo

CalTopo is a top choice for backcountry mapping software for many reasons. One big one is the ease of printing. Let's have a closer look at some of the print features of CalTopo, some obvious and some a little more hidden.

CalTopo, my favorite backcountry mapping software, has a lot of great features. (While many of them are free, you can get a lot more with an annual subscription, which I strongly encourage you to do.)

One CalTopo highlight is superb map printing. Let's have a closer look.

1 - CalTopo generates a “geospatial” PDF

Rather than just spitting out a file to your printer, CalTopo generates a PDF file. (There is a JPG option, but I hardly ever use it.) This makes it easy to save the PDF to your computer, the cloud, and/or email it. This might sound like a trivial feature, but it's really handy. Tip - the “Generate PDF” button opens a new browser tab that shows the PDF. Remember to save or print this file; if you close the browser tab, it's gone and you have to generate it again. You can also save this PDF to your paid account, making it easy to share and organize.

Plus, it's not just a “dumb” PDF file, it's what's termed “geospatial”, or “geo-referenced”. This means that it has real world coordinates embedded in the file. This lets you to use the PDF map in various types of phone GPS apps, such as Avenza, as your base layer. (Personally this is not something I use, but some people find it handy.)

2 - Choose your paper size (depends on subscription level)

A free CalTopo account lets you print only on one paper size. But as you move up in subscription levels, it gives larger and larger printing options. At the basic $20 a year level, you can print on 11” by 17” paper, which is a very convenient size for lots of backcountry trips. By adjusting map scale to a custom number (such as using 1:30,000 rather than 1:25,000) and paper size, you can often print a map for a fairly large area on a single sheet of paper. (Pro and Desktop subscription levels allow printing on pretty much any size paper you want.)

3 - Print at any map scale you want

Many types of mapping software don't give you any option to choose the scale, and they don't tell you what scale the map is even when it does get printed. CalTopo does both. At the top left side of the print dialog box, there’s a dropdown for five or six common map scales. You can also choose your own, under “Custom”. (I often use this feature to make custom orienteering maps, which are often a 1:10,000 scale.)

4 - Choose your DPI (depends on subscription level)

DPI, or dots per square inch, determines the overall quality of your printed map. The default DPI is 200, which is fine for most weekend climbing and backpack trips. Higher subscription levels (Pro and Desktop) give you access to a 300 and 400 DPI option.

5 - Print a UTM or lat/long grid

Having a printed UTM grid on your map can be helpful for several things. It can help you estimate distance in kilometers, lets you plot UTM coordinates from a GPS onto your map, determine your UTM coordinates from your map, and give you a grid that's pretty closely aligned to true north, which can make measuring compass bearings on your map a bit more accurate. You can toggle this grid on or off with one click. I usually choose to have it on.

6 - Print multiple pages

One of the most powerful features in CalTopo is the ability to print multiple map pages, and do so in any combination of landscape or portrait that you want. For example, on a multi-day backpack trip you would probably need to print out several different pages to cover your trip at a reasonably large scale. If your trail runs north-south, you can print in portrait mode. If the trail changes to more east-west, you can print a few pages in landscape. Also, the red box that shows the actual print area is idiot proof and accurate. Click and drag the red print area boxes to determine how much overlap you have between map sheets.

7 - How to print it

Always protect a printed map from the elements. At the bare minimum, use a 1 gallon Ziploc freezer bag. Having the map in a plastic bag also makes it much more resistant to tearing.

It's best to print your map on a color laser printer if possible. Typically I save the map from my desktop computer onto a thumb drive, take the thumb drive to my local office store, and use the color laser printer there for a buck or two.

8 - Other helpful map information

On the bottom margin, CalTopo prints just enough info to be helpful, but not more than you need. You get a scale bar in miles and kilometers, the UTM zone, a ratio scale (like 1:25,000) the map datum (defaults to WGS84), and the correct magnetic declination for your location (declination is often incorrect on older printed maps).

One unique feature of CalTopo maps is a QR (Quick Read) code, printed on single page maps only. If you point your phone camera at the QR code, it can save the map as a PDF onto your phone, very cool! (You can even do this off of a computer screen, you don't even have to have the printed map in front of you.) This means one person can make a PDF map, email it to everyone else on the climbing team, and they then can print it, and/or save the map to the phone with the QR code. I'm a big fan of always carrying a digital backup of a paper map on my phone, and this is a super easy way to do it.

Here’s an example of the bottom of a CalTopo one page map, showing datum, UTM zone, two scale bars, ratio scale, QR code, and declination diagram.

Finally, here's an example of the finished product, for the Disappointment Cleaver route, Mount Rainier.

1:25,000 scale

11 x 17" paper (prints nicely on 1 page)

1 km UTM grid

MapBuilder Topo layer

CalTopo pro tip: elevation profiles

An “elevation profile” is a sort of sideways look at your route, showing distance and elevation gain on a graph. It's a very handy tool to study your route, and making one with the great mapping software Caltopo takes just a couple of clicks.

If you're new to CalTopo mapping software and want to learn the basics, start with this video

CalTopo elevation profile example

Knowing the distance and elevation gain on a hike, bike ride or climb is really helpful. This is known as an “elevation profile” because it shows your route in sort of a side view graph, typically with vertical gain on the left axis and distance on the bottom axis.

In the pre-computer days, this was a very tedious task, involving counting contour lines through a magnifying glass, and measuring distance with a ruler. It was such a hassle that no one except true map geeks ever bothered to do it! However, in these modern times, making an elevation profile with with great mapping software like CalTopo is easy, if you know where to click.

For this example, let’s use a hike / climb of Broken Top, a popular climb in central Oregon. (Or, if you like, you can use any hike you already know.)

Go to caltopo.com and zoom into your area of interest. The default map layer, called “MapBuilder Topo”, is a good place to start.

First, you need a line on your map of your route.

If you know where the trail(s) or route goes, you can draw the line yourself. Right click, choose “New” > “Line”. Click on your starting point, usually the trailhead. You can draw line segments in three ways.

Draw short line segments with a series of clicks.

Draw a freehand line by tapping the control, shift or command key and click / drag.

Snap to an existing trail, shown in yellow highlights. (Sometimes the snap to function is handy, sometimes it's a hassle. You can turn this snap function on / off by selecting “Snap To > None” from the dropdown menu in the top right corner.)

Play around with these for a while to see how they work. Double click to finish your line. To delete a line you don’t like, mouse over it, right click, and select “Delete”.

Note: Don't be too concerned if the line you draw is not EXACTLY on your trail or route. You're not a professional surveyor here, you're just trying to get a general idea of the distance and elevation, so being super accurate is not usually so important.

Also, keep in mind that any estimated distance and/or elevation derived from a computer is always going to be a little different than the real world. The guidebook says that a hike is 10 miles and 3,000 vertical feet, But when you drawn an elevation profile in CalTopo it says it's 10.5 miles and 3400 vertical feet. And, when you hike it with your GPS recording a track, the track show something different. Which one is right? Dunno. How can you tell? You can’t. Does it matter? Probably not. Don't get too hung up on the exact numbers, this is for general estimation and planning purposes.

If you made a line with a series of short line segments, you can move the line a bit to make it more accurate. Mouse over the line, right click, and choose edit. The line should redraw with a series of small white dots. You can click and drag these dots to move that portion of the line. Play around with us to get a feel for it.

You can also make an elevation profile with an imported GPX track file. If you don’t know where your route goes, this is a good approach. On AlpineSavvy you can find tracks for more than 70 of the most popular climbing routes in the Pacific Northwest. For other mountaineering objectives, you can try Peakbagger.com, or some other local website with hiking tracks, such as oregonhikers.org. Sometimes a Google search for “Hikename GPX track” can get you what you need.

For our Broken Top example, when you’ve drawn your route, it should look something like this. (A solid red line is the default.)

After you’ve drawn your route, look on the left side of your screen. Under “Lines and Polygons”, you should see a red line with an “N/A”: after it. This is the line you just drew.

To the right of this, you should see three small icons. The first one looks like a little graph, the second one is a little pencil, the third one is a red X. Give each of these a click and see what happens.

The red “X” is delete.

The “pencil” icon is edit. Here you can add a name for your line, change the color, line style, or line weight. (In the photo below, I changed my line color to purple and increased the line weight a little bit. This is also a good time to add a descriptive name to the trail, such as “Broken Top climb”.)

Finally, clicking the “graph” icon should give you an elevation profile of your route.

If you move your cursor over the elevation profile on the bottom, you should see a corresponding red dot on the map in the upper part of your screen, showing your map location. Pretty cool!

Here’s an extra feature of elevation profile. On the top right of the elevation profile, you should see a small button that’s labeled “expand”. If you click this, you’ll get even a more detailed elevation profile. This shows a few extra whistles and bells like amount of forest cover, slope and aspect of the route, and more.

Looking at the slope coloration along the bottom edge of the line graph, we can see that it's a fairly flat approach up until about the last mile or so. That's about what you’d expect from a climbing route.

This is a lot of words to explain a pretty simple process. Try it a few times and you’ll pick it up quickly.

And yes, CalTopo is terrific. Please consider a modest annual subscription (starting at $20) to support continued use of this great tool.

Click the “Upgrade” menu along the top of the CalTopo screen to see various subscription options.

Great snow climbing tutorial from the AAC

Want to learn some snow climbing tips from the guy who founded the American Alpine Institute and former president of the American American Guide Association (AMGA)? We thought so. While these are some great tips for beginners, even you crafty veterans may learn a few new things.

You know how the biography and qualifications of an author often appears at the end of an article? Well, here’s a link to a great tutorial on basic snow climbing techniques from the American Alpine Club (AAC), and I’ll mention the authors right here, up front - Dunham Gooding and Jason Martin. (Bold text mine.)

Dunham Gooding founded the American Alpine Institute in 1975 and has taught courses and guided expeditions in the Cascades, Canada, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Patagonia. He has served as chairman of the National Summit Committee on Mountain Rescue, president of the American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA), and president of the Outdoor Industry Association.

Jason D. Martin is the director of operations and a senior guide at the American Alpine Institute. He is on the board of directors of the AMGA and has written two guidebooks and co-authored Rock Climbing: The AMGA Single Pitch Manual.

So yeah, If you're going to get climbing advice, these are two pretty good guys to listen to.

This article is about a 10 minute read, and covers just about all of the basics of snow climbing. If you’re a beginner climber, this is an excellent place to start. Even if you've been in the game a while, you may learn a few things. Highly recommended.

Wilderness trip planning, start to finish (video)

There are some fantastic navigation resources online, but it can be confusing how to use them most effectively and where to get started. Watch this video to see one way to plan a climb, from start to finish.

There are a bounty of amazing navigation resources available to the backcountry traveler. Generally, this is a good thing, but it can also be a little overwhelming. What app to use? Where do I start? How do I print free maps? And maybe more specific questions, like:

I found three different GPS tracks for the trip I want to go on, which one should I use?

How can I make a map with the GPS track printed on it?

How can I get the GPS track into Google earth to scope out my route before I leave home?

What's the best way to get the GPS track onto my phone so I can use it with Gaia GPS?

I don't have a track file, but I have a pretty good Idea of where I want to go. How can I draw this track in on a map, print it, and get it onto my GPS?

If you’ve ever found yourself scratching your head with questions like that, we've got you covered with the video below. It covers most every aspect of wilderness trip planning - searching online to find a GPS track for a climb, opening and editing the track in Caltopo, exporting and opening in Google Earth, printing the map, and exporting the GPX file to your phone.

(Hint, parts of the video are best viewed in full screen.)

How to (and how not to) rack pickets

You want pickets clipped vertically to your gear loops or pack straps, not slung around your neck. Here’s how to rack pickets right.

What beginning snow climber has not cursed the clanking cowbells and the strangle, tangle and dangle of pickets, hanging from ill-placed runners around your neck and shoulder, threatening to trip you up at each step!

Here’s a better way to rack pickets. Carry 6 pickets like this, with them more or less out of the way yet still easily accessible. (Think of this method as the least of all evils. Pickets are still a drag to carry, no matter how you do it, but this way sucks the least.)

If you have very firm snow, you might be able to use a “top clipped” picket. In that case, girth hitch a single length (2 foot / 60 cm) runner through the top picket hole. Clip a carabiner to the runner, then clip this carabiner to the third hole from the top of the picket.

If you’re clipping the middle picket hole, you're probably going to need a double length (4 feet / 120 cm) runner. Girth hitch this long sling through the middle hole . . .

Then wrap the sling around the picket until there's a few inches left, and clip the carabiner to the 3rd hole from an end.

Then, clip the carabiner to your gear loop (harness or on your pack waist belt). By clipping the third hole, the picket rides high enough to (mostly) not trip you, and stays oriented vertically.

Another option: clip it to your backpack strap.

This works well for the leader and for the second / gear cleaner.

Rack the pickets (to begin with) on the opposite side of where your ice axe is generally held. For example, if you're heading more or less straight up or traversing left, and you're right handed, rack the pickets on your left side gear loop so they don't interfere with your axe.

And, a related tip on who the cleaner should be. Often the slowest or least experienced person can end up in the back of a running belay, and guess what, that person becomes the cleaner. It's usually better to put a less experienced team member in the middle of the team, and have someone more skilled doing the cleaning at the caboose end of the rope.

Also, it’s helpful if the caboose person is taller; the pickets will ride higher and be less of a tripping hazard.

Here’s a few more tips on the running belay.

Finally, it’s fine to girth hitch the runner through the picket hole. That dyneema sling is rated to 22 kN, weakening it by half with the girth hitch means it's still good for about 11 kN, which is way more force than you're ever going to put on a snow anchor. (But hey, if that's not your thing, feel free to clip the sling to the picket with a carabiner.)

Finally, how NOT to rack pickets: don’t put the slings around your neck and let the pickets strangle, tangle and dangle, like this guy.

Spot, don’t belay, before the first clip

When does a good belayer not belay? Before their partner has made the first clip. Avoid this common beginner mistake.

An all too common scenario at beginner climbing areas is a new belayer attentively clutching the rope with both hands, while their partner is sketching upwards toward the first bolt or gear placement.

Until the leader clips the first bolt or gear, your job as belayer to spot them like they’re bouldering. Both your hands should be up, thumbs tucked into your palm, and your main task is to keep their head from hitting the ground should they fall before they clip.

Anticipate how much rope is needed from the ground to the first clip or placement, and feed enough rope through your belay device so the leader is never restrained while moving or clipping.

The moment they clip, you instantly change to belay mode, with your hand on the brake and feeding rope as usual.

Of course, this is a non-issue if you’re using a stick clip when sport climbing to attach the rope to the first bolt.

Here’s (more or less) how to do it. Note the climbing rope in the right hand, ready to return to belay mode right after the leader makes the first clip.

image: from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S_F1MfVGOzk

And this video, starting about 1: 32

Know how to find your coordinates from your phone

Need to contact 911 when you're in the backcountry? Better have a way to tell them where you are. Learn several ways to get your latitude longitude coordinates from your phone.

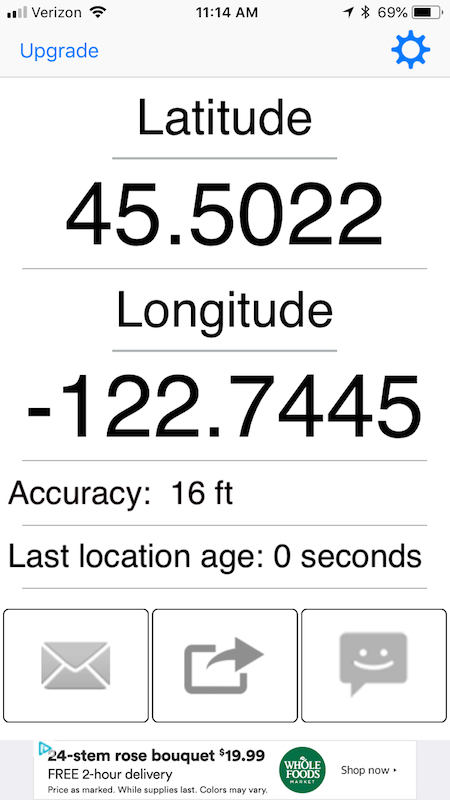

I'll be blunt and say this up front: I firmly believe that every backcountry traveller who has a smartphone should know how to find their latitude longitude coordinates and be able to transmit them to 911 (or an emergency contact person) if necessary.

If you ski in avalanche terrain, you have an obligation to learn about avalanche avoidance. If you climb on glaciers, you have an obligation to know about crevasse rescue. Same thing with hiking in the woods: knowing how to find your coordinates from your phone should be a basic qualification of being a responsible backcountry traveler.

It's not just for contacting 911. You can use a coordinate sharing app to text or email an emergency contact person at home. Sometimes in the backcountry with limited cell coverage, you might be able to send a text but not have a reliable voice connection. Many 911 call centers cannot receive text messages, so in that case your best option would be to text your situation and coordinates to a friend in town, and have them contact 911.

Also, I've heard from some people, “Why should I bother using an app like this, 911 uses some technical magic to figure out my phone location anyway.” Well, that can often be true if you're in a city, with lots of cell phone towers and perhaps even Wi-Fi. But, out in the woods with maybe one bar of coverage, some of that magic cell tower triangulation is not going to work too well. Also, doing that can require you to keep your phone on for a longer time, which could be an issue if you have a low battery and need to conserve it. Overall, it's better to be proactive and learn to get your coordinates yourself.

(This article is geared toward iPhone users, because that's what I have. You Android folks, I'm sure you can follow along.)

Note: It’s best to give your coordinates to 911 in latitude longitude, decimal degree format.

Example: 45.1234, -122.1234

This is the more modern, computer-friendly way to specify your latitude and longitude. It's also a lot easier to say over the phone than trying to describe hieroglyphic-like symbols for degree, minutes, and seconds.

If you tell tell your coordinates in another format, such as latitude longitude, degrees, minutes, seconds (example: 45 32’ 13”, -121 56’ 28”) or UTM coordinates (example , 10T 519984 5035478) Search and Rescue (SAR) can figure it out once they get it. However, it’ll be faster and minimize any translation errors by giving your coordinates in decimal degrees, the easiest possible manner. The decimal degree format is also one that every 911 operator should be familiar with, which should further minimize any source of confusion.

Let's cover a few simple ways to find your coordinates on your phone.

1 - A “show my coordinates” type app (Note, these two are for the iPhone)

One option is to use an app whose main purpose is simply to show your coordinates.

Here’s one I like that’s free and pretty idiotproof - “My GPS Coordinates”. It shows your coordinates in a huge font, and less you text or email those, along with a message.

Tip - You can set the coordinate precision to “low”, or four decimal places, which is your position accurate to about 50 feet. (I feel this makes it easier to transmit your position with enough precision to get you found, but not any extra numbers that could potentially cause confusion or be transcribed incorrectly.)

Here's a screen grab:

Another one I like is called “UTM Position Mailer”. It was free for a long time, now it's $2. It does one thing, and it does it pretty darn well - tells you your exact position in UTM coordinates, latitude longitude decimal degrees, and allows you to send an email or a text with this location information automatically inserted.

If you're calling 911, keep in mind that many 911 operators may not be familiar with UTM coordinates. The better choice is to use latitude longitude decimal degree format, which is universally understood by everybody.

Android folks, try searching in the Google app store for “GPS location”. There are all kinds of free apps. Here’s a free Android app called “My GPS Location”. Shows your location and lets you email or text it.

2 - Dedicated GPS app

I’m a big fan of Gaia GPS. if you have that on your phone and know the basics of how to use it, there’s various ways that you can find your location from the app. Here’s a screen grab with one example.

3 - The iPhone compass app

A quite serviceable compass is built into the iPhone operating system. What a lot of folks don't know or realize is that on the bottom of the compass screen, it tells you your latitude and longitude coordinates and elevation. (Yes, the format of the coordinates is degrees, minutes, and seconds, rather than the more generally useful decimal degrees, but that's certainly better than nothing.) Dear Apple, if you’re reading this, please change the format of your coordinates. :-)

Note that you have to have Location Services turned on for your compass to have this visible. Tap Settings > Privacy > Location Services > Compass, and “Allow Location Access” while using the app.

If you do a long touch on the coordinates at the bottom of the screen, a little “copy” box should pop up, copying the coordinates to the clipboard. You can then paste these into an email or text.

Example of the iPhone compass screen, with lat long coordinates and elevation.

4 - Google Maps

It's not very obvious, but if you know where to tap, you can see the coordinates of your location in Google maps. Tap to copy that and paste in a text. Bonus, it's in the preferred decimal degree format. For the iPhone:

Open the Google maps app. Tap the “black triangle in a circle” icon to zoom to your location.

Long touch on your location. This should open a tab at the bottom of the screen.

Scroll up. You should see the latitude longitude coordinates of that position, looking something like this: (45.1234567, -122.1234567).

Long touch the coordinates, tap copy and then paste into an email or text.

How to clip quick draws 101

Want to start leading sport routes? Clipping the rope into a quick draw might seem simple when you watch an expert to do it, but there are some subtleties that aren't immediately obvious. Learn a few of them with this instructional video.

Any beginner who wants to learn to lead sport/bolted routes will find this video from Outdoor Research to be a solid starting point. And, even if you've been at the game for a while, you still might learn a trick or two.

Do you know the difference between a thumb clip and a finger clip?

What's the right way to hold the rope in your mouth? (Hint, it's not with your teeth!)

When is it okay to high clip, and when is it not?

Clean sport anchors by lowering - New AAC guidelines

When you finish a single pitch sport route, should the last climber rappel off, or be lowered? The debate on this can get pretty hot and heavy, but the momentum is swinging towards lowering. Read why and learn how here.

The sport climbing anchor debate of “should the last climber lower or rappel” debate has raged back-and-forth over many years. It’s not my wish to fan these flames.

But, shared here as more of an FYI, public service announcement, the American Alpine Club (AAC) has officially come out with the stance that they support lowering.

Summary of reasons:

Changing from one safety system to another (from belaying to rappelling), and the potential for communication errors regarding whether a climber is on or off belay, has contributed to many accidents. Here, the climber stays on belay the entire time.

The climber is never untied from the rope, which means they never have a chance to drop it.

No additional specialty gear, such as a rappel device, extra carabiners, daisy chain, tether, or PAS, is required.

The well intentioned rationale for rapping is usually to avoid putting wear and tear on the anchors, but the AAC calls this “. . . misplaced sense of stewardship that seeks to preserve anchor hardware.” Modern anchor hardware is extremely robust, and ideally meant to be easily replaced.

Here’s how to do it:

The second climber climbs the route, cleaning gear as needed.

The second climber arrives at the anchor, and clips directly to the masterpoint of the existing anchor. This connection can be made with either a quick draw, or a tether / PAS.

Remaining on belay, the second calls for slack, pulls up a large bight of rope, and feeds it through the anchor hardware meant for lowering.

The second ties an overhand or figure 8 on a bight, and clips it to their belay loop with a locking carabiner.

The second calls for “tension” or “take”. The second checks to see that they are being properly held by their belayer, the rope is threaded correctly through the anchor hardware, and their carabiner is locked.

The second cleans the anchor material from the bolts.

The second unties the rewoven tie in knot from their harness, and pulls the tail of the rope through the chains.

The second calls “ready to lower”, and lowers to the ground.

To clarify, this does not mean that a group of two or more should initially set up to top rope on the anchors. You should pretty much always do this on your own equipment. This scenario is only for the last person up the route, who needs to clean the gear and safely get back to the ground.

The AAC is certainly not saying that every sport climber should start to do this on all routes tomorrow, nor that it’s best in all situations. But for the AAC to make an official policy statement on this is a pretty big deal, many instruction schools and guiding companies are doing this already. So it’s important for the climbing community to be aware of this, regardless of your own thoughts on the matter.

Here's a nice graphic from Petzl that shows you the step-by-step:

image: Petzl.com

Here's a video from the American Alpine Club, showing this technique. The lowering procedure starts at about 3:10.

Here’s a nice video from AMGA Certified Rock Guide Cody Bradford, see how fast it can be?

While sadly Cody is no longer with us, his Instagram continues to stay up and is a great source of tips like this, check it out.

And here's a longer one, with IFMGA Guides, that goes over the steps in a bit more detail and a couple of different scenarios.

Be cautious of “grade inflation” in climbing gyms

Don't let your head get big because you can climb “5.11” in the vanity gym. You may be in for a big surprise your first time outside.

Many outdoor climbing areas have a reputation for ratings that are relatively easier, or harder, than the generally accepted grade.

Red Rock Nevada? The bulletproof sandstone is sticky, the cracks eat cams, and the bolts are plentiful. You’ll probably feel like Superman and climb a grade or two above your normal level. (But, the climbs are long and committing and the rappels are prone to getting your rope snagged, so bring a headlamp!)

Joshua Tree California? Just about everybody seems to get spanked on their first day. Between the sharp rock that shreds your hands, and flaring cracks that don’t take gear very well, that “warm up” route can definitely feel like a lot harder!

Similarly, some indoor gyms have a reputation for “vanity grades”, meaning what they might call a 5.10 is really more like a 5.8 or maybe 5.9.

If this is the only place you climb, you may start to believe that your ability is higher than it really is. If you then head outside and try a route at this same rating, you may be in for a rude awakening.

To mitigate this: Climb at different gyms and get a sense of how the ratings vary on routes of the "same" grade.

On your first few trips outside, leave your ego in the car. Try routes that are a couple of number grades below what you think you can comfortably climb in the gym. Even if you can lead climb safely in a gym, try top roping a few pitches initially when you’re outside, and consider using a stick clip so you don’t deck before you clip the first bolt.

When making the transition from indoor to outdoor, it’s an important safety issue to have a realistic knowledge of your abilities.

Sure, you might feel like Superman in the "vanity gym", but wait till you try going outside.

Bring a backup map as a PDF file

If you already have a PDF file of a map that you’ve made in Caltopo or other mapping software, why not save a copy to your phone? It’s free, fast and weighs 0.00 grams.

With modern mapping software such as Caltopo, it’s easier than ever to procure or make a PDF file of a good quality map. While you should of course have a printed map with you, why not also have a copy of the PDF on your phone?

(In addition to a map, you can take photos or scans of guidebook pages, or even an entire guidebook as a PDF file, if it's available. Or, you can really go for it and maybe purchase an entire guide book in Kindle format, and keep that on your phone as well.)

The map is free, a PDF file does not “weigh” anything, and it takes just a minute to add it to your phone. Having a backup copy of the map on your phone can be handy if your paper map is lost or destroyed, and it lets you share it with someone on your hike or climb who perhaps did not bring one. You can pan and zoom, and with a good pdf, be able to see even fine map detail.

Android people, I'm not sure about you, but there are several ways to view a PDF file on your iPhone. Here’s how I do it.

Save or download the map to your hard drive.

Email it to yourself and open the email on your phone with the native iPhone email app (not Gmail, Outlook, etc).

Tap the email to download the PDF, this should take a just couple of seconds.

Do a long touch on the PDF file. A window should open that gives different way to view or save it. I use the native iPhone “iBooks) app.

Tap “Open in iBooks”, and the pdf should open for viewing in iBooks.

Below - example .pdf map made in Caltopo of the Adams Glacier route, Mt Adams, WA. (This is a screen grab, the actual PDF file has a better resolution than this.)

How to make the "alpine quickdraw"

You want to avoid having gear dangling below your knees. So, how to rack those 60 and 20 cm slings? Answer: the “alpine quick draw”.

A good rule of thumb in climbing is to never let anything hang below your knees. But what do you do with a single /60 cm or double / 120 cm runner to shorten it up for racking?

Answer: the “alpine quickdraw”.

A simple trick is this method, best described with a photo. This triples up the webbing material, shortening your runner to a manageable length. You can clip to gear it tripled like this, or remove two of the three strands from one carabiner to use it at full extension.

(I learned this crafty trick decades ago, and still remember my fascination at seeing it for the first time. At the time I thought it was the really clever! Hopefully if this is new to you, you’ll think somewhat the same thing. :-)

1 - Start with a runner and two carabiners.

2 - Pass one carabiner through the other.

3 - Clip the bottom loop.

Done! A short and compact draw that hangs nicely on your harness, but is easy to deploy at full length.

Safety note: Having a rubber band or something similar to prevent the bottom carabiner on a sport climbing quickdraw from rotating is fine. But you never want to do this on an “open” sling, as the rope can easily become completely unclipped from the carabiner without you noticing. More details at this article.

Glissading - not always your best option for descent

Glissading - You might have learned how to do it on your first day of climbing school. It can be fun, save time, and your quads muscles in certain ideal situation. But there are also a lot of reasons why you may want to avoid it.

Glissading, the skill of (mostly) controlled sliding down a snow slope either sitting or standing, can be a lot of fun and save you time and legs on the proper slope. Pacific NW routes where this can work well include Mt. Hood south side, Mt. Adams south side, the Muir snowfield on Mt. Rainier, and various routes on Mt. Shasta.

Beginning climbers often learn this technique on day 1 of snow school, and then mistakenly think that it's something to be done at every opportunity. (And, hopefully you learned this on day 1 of snow school as well, but it's worth repeating: never glissade with crampons on!)

However, glissading has some serious downsides, and saving a few minutes on the descent may not always be worth it. Before you glissade, consider these points:

Much greater chance of injury than simply walking (usually a broken/sprained ankle, going too fast and cratering into a rock, talus or scree, or dropping into an unseen crevasse)

You wear out your gear faster (seat of your pants and pack bottom)

You get your butt wet

You can lose gear strapped to the outside of your pack, like trekking poles and crampons unless it’s very well tied down

Questionable time savings – saving 20 minutes on a descent by glissading may not mean so much when you weigh it against the downsides mentioned above, and the fact that a round trip climb may take 8-10-12+ hours.