Alpine Tips

Find free camping on public lands with these mapping tools

Being able to see in real time on your phone if you’re on public lands or not is helpful for all kinds of things, especially finding free dispersed camping spots. Here’s how to use some modern mapping tools like Caltopo and Gaia GPS to do this.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

This is an updated version of an article I published 5-ish years ago.

There are lots of reasons why you may want to see public lands on a map (along with your position). Here are a few.

Personally, I use public lands overlays mostly to find free camping, so that's going to be the main focus of this article. Car camping can be great. Secluded car camping for FREE on public lands that allow it is even better!

You’re headed out for a dawn start for a hike or climb, and want to find a good spot near the trailhead to sleep for the night.

You want to visit a popular national park, but of course all the campsites in the park are booked. Where could you camp for free just outside the park and visit for day use?

You’ve embraced some version of “van life”, and never want to pay if it all possible when you're sleeping in your rig.

You're planning a hunting or fishing trip and want to be sure you don't trespass.

On main roads, you might see a nice welcome sign like this. But on many smaller roads, you won't.

For the most part, land managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and the US Forest Service, (USFS), allow free camping pretty much anywhere unless posted otherwise.

This applies if you don't need amenities like a gravel parking pad, running water, picnic table and a toilet. (The government-speak term for this is “dispersed camping”. RV folks might call it “boondocking”. )

This policy also mostly applies to state owned forest land in Oregon, owned by the Oregon Department of Forestry, or ODF, and in Washington, on land owned by Washington Department of Natural Resources, or DNR. Other USA states may have a similar system.

But, sometimes it’s hard to know whether you’re actually on public land that allows free camping, or not.

Good news is, there’s some good desktop mapping software and phone apps that can answer the question, hopefully leading you to a secluded, free overnight spot with no hassles.

Notes . . .

As cartographers like to say, ”the map is not the territory.” Meaning, what’s really on the ground is the truth, not the printed map or phone app in your hand. If the map says you’re on public land, but the sign on the tree says “area closed” no trespassing, or there are some grumpy locals who are giving you bad vibes, use your common sense and move on.

Leave No Trace principles of course apply. Is this obvious? I sure hope so. Don’t camp in meadows, near waterways or other fragile areas, leave zero garbage, toilet paper or fire rings behind, be VERY careful with campfires (if you even choose to have one) and observe all rules regarding fire closures, which are common in the summer. Have a walk around and pick up somebody else's trash before you leave.

When using a phone app, be sure and download your area of interest when you have Wi-Fi or cell coverage before you get out of cell coverage.

Rural gas station attendants are often great sources for good free campsites. A small tip offered for your gas before asking can work wonders. =^)

Desktop: Caltopo

For this example, let's look for possible camping spots near the Crater Lake National Park in southern Oregon.

Go to CalTopo.com, my favorite backcountry mapping software, and zoom into your area of interest; here’s Crater Lake NP. Choose a map layer. I like “Mapbuilder Topo”, the default.

Then, mouse over the map layer menu in the top right corner, and check the box next to “Land Management”, under the “Map Overlays” section.

Now, your map should look something like this. Note the clear boundary between the National Park land around the lake, and the green tinted National Forest lands around the park.

Now we’re talking! Look at all those logging roads (in the red box) just outside the main road that leads into the park from the west, all on National Forest land. Most of these should offer some decent, free dispersed camping options, just a few minutes away from the park boundary.

Here’s one more. This is just outside the main entrance station at the southwest corner of Mt. Rainier National Park. Check out those roads on the green Forest Service land; looks like a good place to camp for free and then go into the park the next day.

Phone apps - Gaia GPS “Public Lands” overlay

Phone based apps of course have the big advantage of showing your real time location AND the land ownership around you. Here are two that I like.

On the “professional version” of the app, which is $40 a year, Gaia GPS has a map overlay option called “Public Land US”. With the “pro” version, Gaia has an advantage of being able to adjust the opacity of the map layers with a slider bar, which can be a big help in seeing smaller roads and pull outs.

Below is a map legend for Gaia GPS that shows the different public lands layers.

Here we have the map layers “USFS 2016” and “Public Land (US)”. We see a brownish tint for the National Park, and a green tint for the surrounding Forest Service land.

Zooming into the same area where the main western access road enters the park, we see all of the forest service roads, many of which should offer some good camping options.

Phone apps - Gaia GPS “Gaia Topo” free map layer

Recently, a GaiaGPS made some significant upgrades to their primary map layer, called “Gaia Topo”. (One great thing about this layer, it's free, both on the desktop and on your phone.) One of these improvements is showing public lands right on the map. Here's an example around Mt Rainier. (Please ignore the waypoints and climbing routes on the map.)

The subtle shading on this map shows different types of public lands.

Along the main road Hwy 706 coming into the park, you pass through State Forest lands, shown in light purple.

South of the park is light green, which is National Forest.

Slightly darker green is a designated wilderness area (no roads or car camping there).

Finally, the light brownish orange is the National Park itself. Note, there is no dispersed camping allowed in national parks, but the State Forest and US Forest land should be fair game. Note there are lots of roads in both these areas; you need to zoom in more on the map to see them.

Gaia GPS Public lands example using Gaia GPS topo

Want to see my suggestion for an up-and-coming phone app with a great public lands layer?

How about the GPS coordinates for my go-to free camping area right outside Yosemite National Park?

Join my Premium Membership to read the rest of the article.

Thanks for your support!

New from CalTopo - high resolution slope angle shading

CalTopo, the best backcountry mapping software, just got even better. The slope angle shading is now at an even higher resolution, improving wilderness trip planning for much of the United States. See some examples here.

If you’re new to CalTopo and want to learn the basics, start with this tutorial video.

Note: this type of slope shading is made with an elevation model that may not show all relevant features and potentially hazardous avalanche slopes. It can be a useful tool for macro level trip planning, but is not accurate enough to completely assess potential avalanche hazard across all types of terrain.

Slope angle shading is a very cool feature of CalTopo, the best backcountry mapping software. It’s handy for lots of different reasons, and we cover them in detail in this article.

Canyoneers or photographers, looking for seldom-seen waterfalls?

Backcountry skiers, looking for a low angle ascent and a slightly steeper downhill?

Winter travellers looking to (hopefully) avoid avalanche slopes?

Cross country hikers or mountaineers, looking for the path of least resistance?

Slope angle shading can help in all of these situations. Now, the digital mapping data that underlie the slope model is improved, and the resulting shading is much higher resolution.

Here’s a comparison of the old and new slope angle shading, with the Disappointment Cleaver route (red line) on Mount Rainier. The top image is the older style shading, the bottom image is the newer one, using the higher resolution LIDAR data.

Pretty cool to see how the route picks it’s way up through the path of least resistance. You can use this feature to plan a cross country travel route in CalTopo for a place you've never visited! (Of course, glaciers can change on a daily basis and you should never fully rely on a model like this, but it’s a great start.)

Caveat: This new data set does not cover all of the United States, and is sadly lacking in many parts of the western US, but hopefully that will be improved in the next few years as additional LIDAR data are collected. See the data coverage map below. (Sorry Wyoming, Montana, and Sierra Nevada.) Good news, you are highly unlikely to be caught by an avalanche in Louisiana. =^)

Below is a copy/paste from the CalTopo website, Dec 20 2019.

http://caltopo.com/about/2019/12/20/high-resolution-elevation-data/

“CalTopo first launched the slope angle shading layer 7 years ago, and since then it has become a mainstay tool for backcountry trip planning. Today we're updating the layer to incorporate high-resolution LIDAR data from the USGS's 3DEP program. Where available (see coverage map), this provides significantly higher resolution, even allowing you to identify trails from relief shading. As additional coverage becomes available we will add it to this layer.

While the LIDAR data is very high resolution, it should still not be relied on as a definitive source of truth. Beyond possible errors or accuracy issues with the dataset or our processing of it, the surface angle on top of a snowpack may not match the bare-ground angle underneath. Carefully assess and evaluate any terrain that you are traveling in, and confirm your observations instead of relying solely on maps.

This update is now live on the web! It will be released soon on iOS and Android. Offering online access for free, and offline downloads with a CalTopo subscription. The significant increase in resolution means the offline downloads are larger in size than previous elevation data. Be cautious downloading using mobile data and storing on your phone, storage may go quickly.

As with previous expansions of the slope angle shading layer to Canada and Alaska, the high resolution dataset is not available to third party apps that license CalTopo's pre-rendered layers like Gaia GPS and Backcountry Navigator. You can only access the layer via CalTopo's website and app; we encourage you to download the new app to use this layer in the field.”

See the correct declination in CalTopo

When using a compass, it's important to know the magnetic declination for your area. Websites like magnetic-declination.com make this easy. You can also see it in CalTopo, right at the bottom of the screen.

(If you want to learn the basics of using CalTopo, start with this tutorial video.)

Magnetic declination is the angular difference between true north (North Pole) , and magnetic north, which is where the red end of the compass needle points. This changes depending on where you are in the world, and it also changes over time. If you’re using an older map, the declination printed in the margin might well be incorrect.

(If you want the full scoop on declination, watch my video here.)

So, whenever you're using a compass, it's important to know the correct declination for your local area. One good way to do this is to check the website magnetic-declination.com, as we cover in this article.

Here's another way. A helpful little feature I just discovered in the best backcountry mapping software, CalTopo, is hiding in plain sight at the bottom of the CalTopo screen - the correct magnetic declination for (I think) the center of your screen.

(I've been a fanatic CalTopo user for many years and never noticed this before today. Who knows how long it's been there and I just never saw it? =^)

Here are a few examples. (Depending on your web browser, it might look slightly different than this; I’m using Chrome on an iMac.)

Declination for Seattle, about 15° east.

Boston? About 15° west declination. (Don't worry, that won't help you in Boston, you're still going to get lost driving there. =^)

How about New Zealand, a country with some pretty extreme compass declination because it's fairly close to the south magnetic pole? 24 degrees east.

Finally: If you print a map in CalTopo, the correct declination is shown in a diagram on the bottom right of the PDF file.

How to transfer GPX files from Google Drive to the GaiaGPS app

Storing your GPX track collection in Google Drive is handy for a lot of reasons, but moving a file from there into Gaia GPS is not very intuitive. Here are two ways to do it. (OK, not a climbing trip directly, but still can be helpful.)

Upfront disclaimer: this is really not much of a climbing tip. It's more of a computer geek tip, but if you have a collection of GPX track files in Google Drive, you might find it helpful. We’ll get back to our regular climbing tips after this one, I promise.

It's handy to keep a collection of good GPX track files in Google Drive, because you can access them from pretty much anywhere to either use on your phone or share them with your hiking or climbing partners. GPX files are just small text files and hardly take up any room, so when you find one that you think you might have a use for in the future, download it and save it! (Even if it's unlikely that you will go on the trip, you might be able to share it with someone else and help them.) Personally, I have hundreds of GPX tracks on my Google Drive, organized in folders for climbs, hikes, mountain bike rides, road bike rides, ski tours, etc.

However, most people do not find it very intuitive to move the files from Google Drive into a backcountry GPS phone app such as Gaia GPS.

But, like most computer related things, it’s easy once you know how. Here are two ways to do it, one method via a desktop computer, and one method all on your phone. (These instructions are for the iPhone, which is what I have, Android folks probably can do something similar.)

To do this, you’ll need:

a Google account with Google Drive

a folder on Google Drive with some GPX files in it

an account at GaiaGPS.com

the Gaia GPS app loaded to your smartphone.

Method 1 - Desktop / laptop computer

Step 1 - From a desktop / laptop computer, go to Google Drive, navigate to the GPX file you want, right click, download to your computer.

Step 2 - Go to GaiaGPS.com account, click your username or photo in the top right corner, and choose “Upload” from the drop-down menu, screen grab below. Navigate to the GPX file you just downloaded, and select it. (Personally, I do not find this website very intuitive to use, so I thought I’d spell out how to upload a file.)

Step 3 - Open the Gaia GPS phone app. Go to Settings > Account, and toggle the “Sync/Backup” off and back on. Doing this should synchronize all the geo-data in your GaiaGPS.com account, including the track file you just uploaded, with your phone. (The GPX track you just uploaded will probably appear in Saved > Folders on your app.)

Method 2 - Google Drive on your phone to Gaia GPS on your phone

Step 1 - Open the Google Drive app on your phone, navigate to the GPX file you want to use, and tap the “three dots” icon after the file name.

Tap “Open In”. This downloads the file to your phone and gives you an option of several apps in which to open it.

Scroll sideways if needed and select “Copy to Gaia GPS”. This should launch the app and import the file. To see your file, tap Saved > Folders.

Warning, computer nerd stuff only, but it could be useful…

Occasionally, Gaia GPS has a hard time importing / uploading a GPX file direct from Google Drive. This is often because of an “XML “ tag in the first line of the file. Sometimes when Google sees this XML code, the file is not recognized as being a GPX and you are not given the option of the Gaia app to open it.

There are two workarounds for this that I’ve found.

Workaround #1 is to use method one above,: download the GPX file to your desktop, and then upload it to your account at GaiaGPS.com.

Workaround #2 is a little more involved. Open the GPX file in a text editor, and it should look something like the file below (which is a small one of about 10 waypoints.)

Notice the highlighted text in the very first line? Delete all the text between the <brackets> plus the brackets. Save as a new file name, move it back to Google Drive, and it should work fine Google Drive to your Gaia app using the “Open In” method above.

Google maps to GPX file with MapsToGPX.com

If you find yourself driving a lot to remote trailheads without good cell coverage, you may find that Google maps and driving directions don't always work so well. Here’s a cool way to make a GPX track from Google driving directions, which you can follow on your phone or GPS device without cell coverage.

Thanks to my friend and expert boondock backroad navigator Daniel Mick for this tip.

Navigation on a hike or climb is more than what you do with your feet. Driving to an obscure trailhead can sometimes be the navigational crux of the whole trip. Mapping apps work great in town when your destination has an address, but what if you're looking for a trailhead or campground?

If you have the latitude longitude coordinates of a trailhead (or anything else) you can copy/paste the coordinates into Google maps and get driving directions and a map to the trailhead. (Learn how to find lat long coordinates for anywhere at this article.)

If you have decent cell coverage, this should be all you need. But in more remote areas, Google maps sometimes falls short, and you may want to take this extra step of following a GPX track instead.

Below, learn how to create a GPX track file from a Google map. (Like most things in life, it's easy once you know how.)

Why is a GPX track an improvement over the normal driving directions in Google maps?

Outside of cell phone coverage, Google maps can do some strange things. The map detail can be significantly reduced, even if you download the map. Google maps has no terrain or contours shown, so it can be trickier to see your precise location.

However, once you have a GPX track of your driving route, and a quality GPS app on your phone like Gaia GPS, you can choose whatever map base layer desired (topo, satellite, Forest Service, Open Street Map) you like. You can annotate maps with additional navigation notes, such as good car camping spots, locked gates, private property, etc.

You can also record a track of your route when you’re driving. This can confirm your exact location, which fork you took on that last intersection, and keep a record of any change in your route (locked gates, washouts, logging road change, etc.)

If you find yourself driving to a lot of remote trailheads far away from cell phone coverage, this might be a good navigation trick to have in your toolbox. This might look a bit complicated when you first read about it, but after you get the hang of it it really takes just a few minutes.

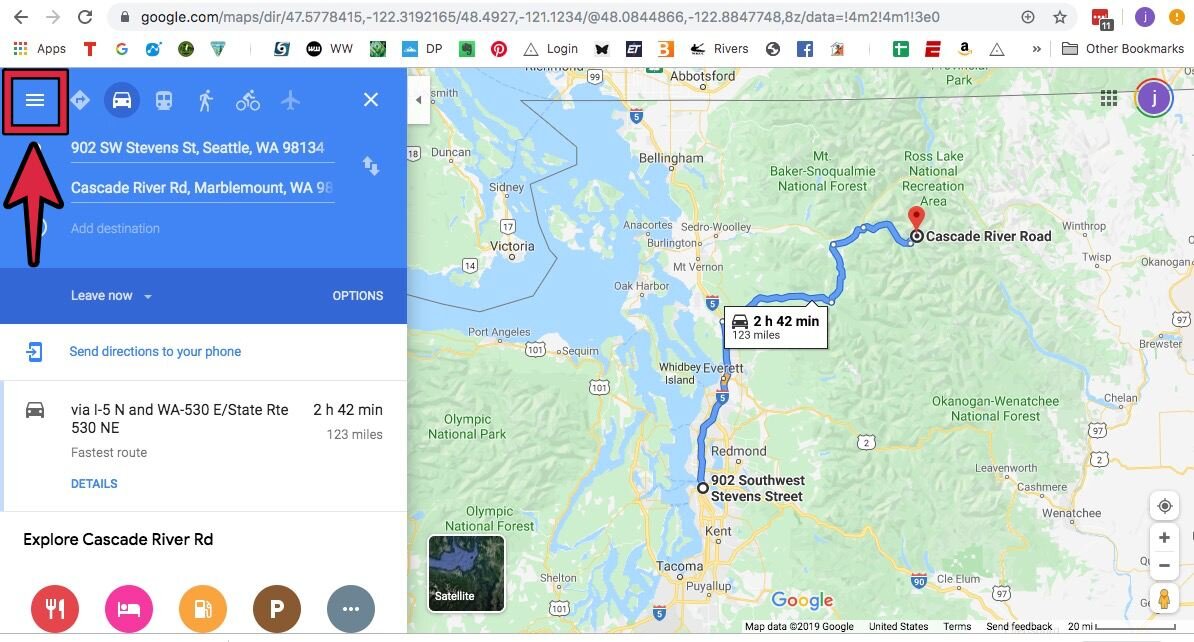

For the example below, we’ll use driving to El Dorado Peak, a popular climb in the North Cascades in Washington.

Here’s how to do it.

Step 1 - Find the latitude / longitude coordinates of your trailhead.

Probably the easiest way to find the coordinates of a trailhead is to have a GPX file of the entire hiking or climbing route. Import this GPX file in CalTopo, notice where one end of the track reaches a road, right click at that point, choose New > Marker, and copy the coordinates that appear in the box in the lower right corner.

(Note: There are three different formats of latitude longitude coordinates. By far the easiest one to deal with is called decimal degree coordinates, which look something like this: 45,1234, -122,1234.)

For example, the El Dorado Peak trailhead has lat/long coordinates of: 48.4927, -121.1234

Step 2 - Copy and paste these coordinates into the Google Maps search box. Click Enter.

Step 3 - Click “Directions”. This should give you driving directions from your current location to the trail head.

(Tip - If you don't need directions right from your front door, you can click and drag the little dot at one end of the direction line to a new location. Below, I moved it from Portland to Seattle to simplify things.)

Step 4 - Click the “3 horizontal bar / More” icon in the top left corner.

Step 5 - Click “Share or Embed map”

Step 6 - Copy the "Link to share” URL

Open a new browser tab. Go to “mapstogpx.com”.

Paste the Google directions “Link to share” URL into the box.

Click “Let’s Go”. This should download a GPX file of the Google driving directions.

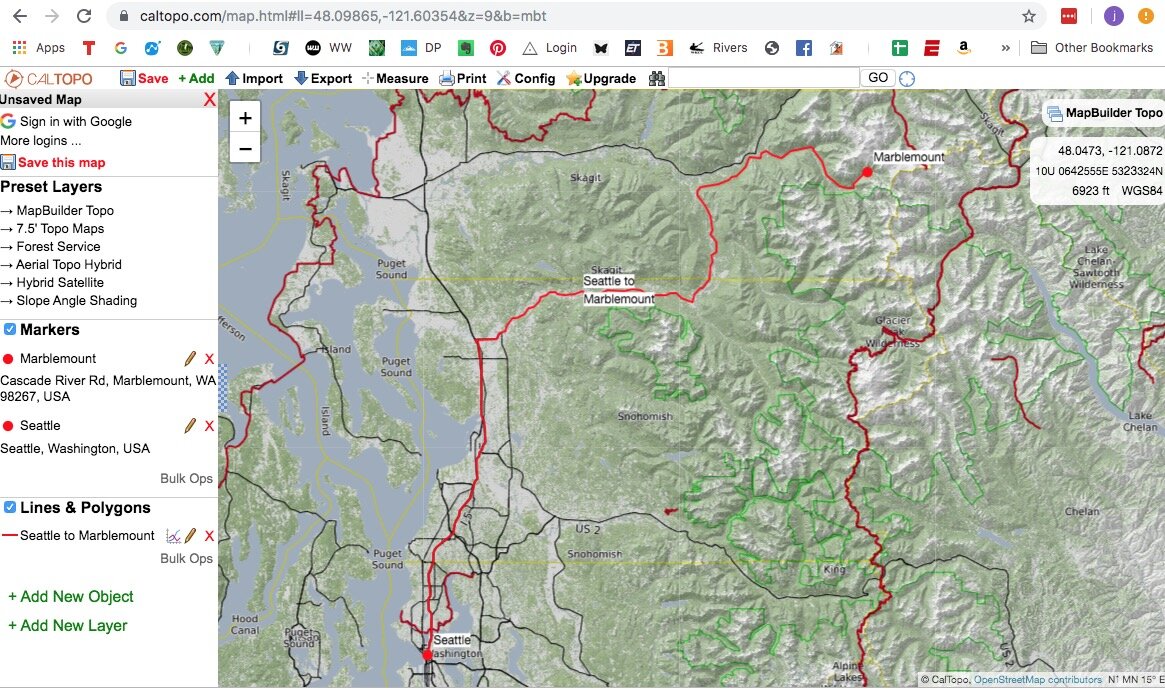

Open caltopo.com and import the GPX file. It should draw correctly, as seen below.

Make any edits or additions to the driving route, such as locked gates, camping or meeting spots, sections of rough road, any known closures or detours, etc.

When you're all done, export the GPX file from CalTopo and save it to your computer.

Now, you can put the GPX file onto your phone or GPS device for confident navigation outside cell coverage. If you use Gaia GPS, which is my favorite backcountry GPS app, the easiest way to get the file to your phone is to go to Gaia GPS.com, click your username in the top right corner, and choose “Upload” from the drop-down menu. This will sync the file from GaiaGPS.com to your phone app.

Finally, here's what the track looks like after importing it to my Gaia GPS phone app. It’s a perfect track to follow to the trailhead, even without cell coverage.

View snow levels and your route in Google Earth

Wondering how much snow is on your intended hike or climb? Learn how to view your route and an overlay of current snow levels in Google Earth.

Thanks to Alpinesavvy reader Lucas Norris for introducing me to this great tip.

Upfront disclaimer, this article is generally for people who are pretty geeky about maps. Hopefully you’re one of them. =^)

In a previous article, we covered how to download a map with real time snow depths in the US and part of Canada. This is a pretty handy tool for trip planning, but there's potential to make it even better.

What if you could see this snow depth data overlaid onto your actual drawn route, AND in the 3-D splendor of Google Earth? Turns out you can. Here's how to do it.

Tip - I have not tried this in the web browser version of Google Earth, only on Google Earth Pro, which is free software you can download onto your desktop computer. I recommend doing this in Google Earth Pro.

For this example, we’ll be using the Wonderland Trail around Mount Rainier.

Step 1 - Get a GPX track file of your intended route. We cover how to get track files for climbing at this article, and for hiking at this article. You can find a track for the Wonderland trail at the “Pacific NW Long Hiking Routes” section right here at Alpinesavvy.

Step 2 - Convert the GPX track file to a KML file, a type of file that plays well with Google Earth. One easy way to do this is to go to caltopo.com, import your GPX file, and then export it as a KML file. Use the Import and Export menu bars at the top of the screen.

Step 3 - Import your KML file to Google Earth. Launch Google Earth. Double click or drag and drop the KML file into Google Earth. It should draw up as a red line and look something like this. (Yes, pretty damn cool!)

Step 4 - Get the snow data. Go to this website.

https://www.nohrsc.noaa.gov/earth/

You probably want the most recent data, which will be the top of the left column, under “Snow Analysis Overlays.” In the image above, that would be the link for November 18. (You can also see historical data under the “Archive” link at the very bottom.)

This will download a KMZ (another filetype that plays well with Google Earth) file of the snow data to your hard drive. Double click on this or drag and drop to open in Google Earth.

Very cool! This is the real time snow cover over the entire United States and most of southern Canada. (As I write this in mid November 2018, you can see it's been a very light snow year so far in the western United States.)

Step 5 - Zoom into Mt Rainier. With the snow depth level data loaded and a KML file of your route also loaded, your screen should look something like this.

It appears it if you wanted to get in a late November hike in 2019 of the Wonderland Trail, you should be able to do it with hardly any snow, kind of a rarity here in the Northwest.

mtcams.net - Time lapse webcams of iconic mountains

This clever website, created by Ben Stabley, shows you time lapse and historical webcam images of both major northwest peaks and iconic mountains around the world.

Mountain webcams can provide real time images of recent storm activity, snow cover, and sun/shade on different features at different times of the day. This info might help you make a decision of your preferred route and equipment, and give you another tool beyond an avalanche and weather forecast.

But, webcams are usually a static snapshot of the current time, you often can’t look at historical images, and finding reliable webcams can be hit or miss.

Here’s a solution to all that. Portland-based geographic data wiz Ben Stabley has a streamlined website for viewing time lapse images of major mountains - mtcams.net.

His website works great on a mobile device as well as a desktop computer. You can see webcam images of Hood, Three Sisters, Rainier, Baker, Shasta, Whitney, Grand Teton, Mont Blanc, Fuji, and the Eiger. (Other major but more remote peaks are not included because they generally lack good quality webcams.)

The website is pretty intuitive, you can click around for a minute or so and figure it out. Here's a step-by-step.

Choose the mountain you want to see.

Choose “From” and “To” dates.

Press “Load Photos”.

This brings up three tabs, the middle one is “Time Lapse.” Choose from one frame per second up to 30 frames per second. You’ll then see a time lapse image of webcam photos of that peak for your chosen date period.

Notice that the webcam interval is different depending on the mountain. For example, the Mt. Hood camera grabs an image every five minutes, while the Mt. Fuji camera grabs one image per hour. So experiment with the “frame per second” option until you find a time lapse that looks helpful.

It's also fun to go farther back in time rather than just the last few days. Wondering what the snowpack was like on Mt. Rainier in late July three years ago? You can do that. (Note: imagery starts in 2017, so nothing before that.)

Where can I find GPX tracks for hiking trails?

When you have a GPX track for a hiking trail, it can show you the trailhead location, give you an elevation profile with distance and vertical gain, and of course help you stay found on your hike. Here are some websites where you can download free tracks for hiking.

As we like to say at Alpinesavvy, having a map is great, but having a map with your route printed on it is even better. And, having that route on your phone with a quality GPS app like Gaia GPS is another plus.

Knowing your route usually starts with a GPX file, which is a standardized format for sharing geographic data. A GPX track file is a simply a text file with a long string of latitude and longitude coordinates (and sometimes time and elevation), and a line drawn between them. This shows a hiking or climbing route that someone has recorded in the field or (hopefully) carefully drawn in mapping software. (If you can't find what you want, you can draw in your own route in mapping software like our favorite, Caltopo.)

Why do you want a GPX file? If you have a GPX file, you can print a PDF map of your route in CalTopo, which looks something like this (Hamilton Mountain, Columbia River Gorge)

Or, you can download it to Gaia GPS or your preferred GPS app/device, so you can use it for navigation in the field, here's a screen grab of that (Hamilton Mountain, Columbia River Gorge):

Historically, it's been quite difficult to find a consistent, quality source of GPX tracks for hikes and climbs, but that’s changed for the better in the last few years.

Here are two good websites where you can download free GPX files for hiking trails - GaiaGPS and AllTrails.

Hiking - GaiaGPS.com

Gaia GPS is my favorite backcountry navigation phone app. In addition, the GaiaGPS.com website has steadily improved and it’s now is a solid place to locate hike track files, provided you know where to look. Plus, if you already use their app, a big timesaver is that you can save a hike description or hiking track directly onto your phone with one click.

Note: You need to have an account at GaiaGPS.com for this to work, and the below examples are shown on the desktop website, not on the app. (The app has some pretty good built-in hike finders as well, but we're not covering that today.)

Here's how to do it.

Click “Hikes” from the top menu bar.

Search for the name of the hike you want, or use the map finder to zoom into your area of interest. (The search function can be a little hit or miss; it can help to type in the state you're looking for so you don't get results from all over the world.)

Once you find the hike you want, give it a click. The easiest way to save both the track and a lot of info about that hike is to click the big green “Save Hike” button at the top right corner. This saves pretty much that entire webpage on your phone, with distance, elevation gain, recent trip reports, and of course a base map with the GPX file.

On your phone, this is saved under the “Saved > Hikes” icon along the bottom of your screen.

Also helpful: along the bottom are icons for “Copy Link” and “Share”, which lets you send that webpage easily to your other hiking buddies. (From what I can tell, it's pretty much the same as a copy paste of the web address.)

If you want to see other Gaia users’ uploaded tracks of the same area, which might show some detours or other areas of interest off of the main hike, you can do that too. Scroll down the page a bit, until you come to “Public Tracks”. This shows a link, and often a bit of a trip report. If you click on any one of these links, it will open that person’s track in a new window, and you can download it if you want.

And, a whole other way to look at these data is to use the Gaia “Public Tracks” overlay, which shows the recorded tracks of everyone who has shared a hike in that location. We cover how to do that at this tip.

Often it takes a few minutes before Gaia GPS can synchronize with your phone. If you download the hike or GPX file to your GaiaGPS.com account, and it's not showing up on your phone, You can force the synchronizing to happen like this: Go to the Gaia app, Settings, and toggle the “Sync/Backup” button, shown below.

Hiking - Alltrails

Alltrails is another good choice for day hikers to find quality GPX files. The website has a clean interface, and lots of functionality even on the free version.

To find a GPX track, zoom into your area of interest and choose the hike you want, here Hamilton Mountain in the Columbia River Gorge. Tap the “More” link on the left side. From this drop-down menu, select “Download Route” to save the GPX file onto your computer.

Once you have that GPX file on your hard drive, you can import it to Caltopo and print a map or save as a Google Earth friendly KML file, upload it to your guy GPS account to put onto your phone, or share it with your hiking partners.

Where can I find GPX tracks for climbing routes?

If you want your climbing route drawn on a map, or a track to follow on your GPS, it usually starts with a GPX file. Here’s how to take a dive into Peakbagger to get the file you need to stay found.

Thanks to my friend and Peakbagger.com expert Daniel Mick for assistance with this article.

Disclaimer 1: A GPX track file shows an approximate route, not necessarily the best one for you to take based on current conditions. Mountain landscapes, especially snowfields and glaciers, can change on a daily basis. A track recorded on a dry summer day might be not show the best route when wet or snow-covered. Carefully preview the route on a map before you leave home. Don’t blindly follow a GPS track In the field if it doesn't make sense. Any GPX file you download from the Internet can be suspect.

Disclaimer 2: Do not rely on a GPX track file to show you the way on technical climbing routes. If you're at the base of the third pitch and you're wondering if you should take the left crack or the right crack, your GPS is not going to help. Due to you moving slowly and that the GPS signal can bounce around on a vertical cliff, the accuracy is just not there. So, you can use it for the approach hike, but not on vertical terrain

As we like to say at Alpinesavvy, having a map is great, but having a map with your route printed on it is even better. And, having that route on your phone with a quality GPS app like Gaia GPS is another plus.

Knowing your route usually starts with a GPX file, which is a standardized format for sharing geographic data. A GPX track file is a simply a text file with a long string of latitude and longitude coordinates (and sometimes time and elevation), and a line drawn between them. This shows a hiking or climbing route that someone has recorded in the field or (hopefully) carefully drawn in mapping software. (If you can't find what you want, you can draw in your own route in mapping software like our favorite, Caltopo.)

Once you have a GPX track, you can print a PDF map of your route in Caltopo, which looks something like this (Mt. Rainier, Disappointment Cleaver route):

Or, you can download the track to Gaia GPS or your preferred GPS app/device, so you can use it for navigation in the field. Here's a screen grab of that (Mt. Rainier, Disappointment Cleaver route):

Historically, it's been quite difficult to find a consistent, quality source of GPX tracks for hikes and climbs, but that’s changed for the better in the last few years.

Of course, right here on Alpine Savvy we have a curated collection of more than 70 GPS tracks of the most popular climbing routes in the Pacific Northwest. So, If you want to climb one of these more common routes, that’s a great place to look first. But, if you can't find it there, check out Peakbagger.

Peakbagger.com is a great place to find quality GPX tracks for climbing routes.

If you're after more technical mountaineering/scrambling routes, I have yet to find any better source for GPX tracks than Peakbagger. Yes, the website looks like it was designed in 1996, but don't let that stop you, there's some amazing functionality once you drill down.

Peakbagger is arguably the best one-stop-shop for mountaineering information, with trip reports and GPS tracks, heaps of links to weather, maps (CalTopo, Google, Bing, etc.), and other mountaineering websites (SummitPost, Peakfinder, books on Amazon). Plus, it’s a compendium of global bucket lists of every variety and flavor (elevation, prominence, state/country, county high point, etc.

But for our purposes, we're only interested in finding GPS tracks. Here's how to do it. (When you first look through these instructions, they might seem long and complicated. Trust me, they're not, once you get the hang of this you can work through it in a minute or two.)

For this example, let's say we want a GPX track of the North Ridge route on Mt. Baker. To start with, type in a keyword from your peak name in the “Quick Search” box in the top right corner.

Depending on your search term, you might get a lot of answers. Check that the location and elevation is for the peak you want. Click the “Name” link in the second column when you find the right one. Here, it happens to be the first choice.

Scroll down toward the bottom of the page. Under the section “Ascent Info”, click “Show all viewable ascents/attempts”. For more obscure mountains you might get just a handful; Baker has over 1,200!

This brings up a spreadsheet format of all of the recorded climbs. (For mountains with fewer reports, you might see a spreadsheet that shows all of the climbs without separate years. Here for Mt. Baker, with thousands of reports, they are broken down by specific years.) We want to see everything, so click “All”.

Just like a spreadsheet, if you click on the column names, it sorts them alphabetically. Click on “GPS”. This shows only the trip reports that have a GPS file. Excellent, out of more than 1,200 trip reports, we just narrowed it down to only a few dozen that have a GPS track. (You‘ll see many climbers do not name their route, not useful! Peakbagger users, please be helpful to everyone else by at least naming your route and better yet, contributing a GPS track.)

Under the “Route” column, look for your route, in this case, North Ridge. (If you can't find the route listed, but you do see a GPS link, you might need to click that link and look at a preview map to see if it's the one you need. In this case we have a half dozen examples of the North Ridge, so we don't need to do that.)

Right click on the “Ascent Date” in the first column that has a GPS link for your route, and choose “Open link in new browser tab” so you can have a look at the actual GPS tracks.

Another useful aspect of Peakbagger is the “Ascent Date” column. Some routes can change significantly whether it’s snow covered or not. If you have the choice, you probably want to look at a route that’s from about the same time of year that you intend to go.

Here we finally see something pretty useful: a GPX track of our route drawn on a map. Have a look at a few tracks drawn on the preview map, they should all look pretty much the same. (Of course, routes on glaciers and snow fields can change a lot from season to season.)

If the route looks good, click the link under the map, “Download this GPS track as a GPX file.”

Done!

Tip: there's no rule that says you only have to download one track. In some cases with tricky route finding, you might find that having several different tracks on your phone or map can be helpful. In Gaia GPS, you can toggle the visibility of different tracks on or off if you find they’re getting distracting.

Below is a screen grab from Caltopo, with three different tracks on it for the North Ridge route on Mt. Baker. You can see that there is quite a bit of variability in the approach, which you would expect on a glacier with changing conditions. Also, when you get up near the summit, there appears to be a couple of different options as well.

Also note that the recorded tracks on the ascent vary a lot from the “North Ridge Route” line drawn on the map! As cartographers like to say, “the map is not the territory”, meaning the real world is what you should follow, not necessarily a line on a map. Yet another reminder that routes on glaciers can change a lot!

Use Google Drive off-line to store trip documents

It’s helpful to have documents (pdf maps, GPX track, guidebook scans, trip roster, etc) related to a hike or climb available offline on your phone. It's easy to do in Google Drive if you follow these steps.

This tip comes from AlpineSavvy reader Tim Donner, thanks Tim! Disclaimer: this tip is not directly related to alpine climbing, but it's pretty handy, so here it is.

Say you’re planning a climb or backpack trip. Useful documents for pre-trip study and field use could include:

.pdf map(s) made in Caltopo, perhaps at a couple of different scales covering your entire route, ideally with a GPX track file of your route drawn on it

a .gpx track file of your route

a scan or photograph(s) of guide book pages

Google Earth screen grabs, ideally with a KML file of your route drawn on it

If you're leading a larger group, perhaps: 1) a roster of trip participants, with personal and emergency contact info; and 2) a general info document (prospectus) for participants with all needed trip details

Here's a convenient way to store all the documents you might need for a hike or climb off-line on your phone, and have access to them when you’re outside cell coverage.

A few notes:

The instructions below are for iPhone; Android peeps, I'm sure you can follow along.

I find it easiest to do this on a desktop computer.

This method uses the cloud on Google Drive, so to do this, you need a free Gmail account. It’ll probably work on other types of cloud storage like Dropbox, but I'm going to stick with Google drive for this example.

Here’s how to make files available offline in Google Drive:

On your desktop computer, assemble all your trip documents in one folder.

On your desktop computer, open Google Drive and make a folder there for your trip. For example, “Rainier climb 2019”.

On your desktop computer, click and drag all relevant files into this Google Drive folder.

Open the Google Drive app on your phone, and navigate to the folder.

Tap on the “three little dots” icon to the right of the file name, and tap “Make available offline”. You need to do this individually for every file in the folder, but it just takes a second or two for each one. (To be clear, you can’t set the available offline feature for the folder, you have to do it individually to each file.)

Done! Now, all these files stored on your phone, available when you’re outside of cell coverage.

To test it, turn on Airplane mode and turn off Wifi. (Doing this simulates being in the backcountry with no cell coverage.) Try opening all of the files in that folder, you should be able to do so.

One more bonus, you can share this Google folder with everyone else on your climbing team, so you all have the same documents. To do this, navigate to the folder in Google Drive from your desktop computer, Click the folder name at the top, and choose “Get shareable link” from drop down menu. Click the “copy link” button, and now you can share that folder with anyone else on your trip.

Once you’re home, deselect the offline use to free up storage on your phone. The files stay in your Google drive for reference or sharing, if you want to do that hike or climb in the future.

One more bonus: with offline use, if you have a Google doc ready, you can add/update notes during the trip and they will be synced once you get back into cell range.

A few screen grabs of the process. . .

In Google Drive on your phone, tap the “three dots” icon next to a file name . . .

Then tap “make available offline” for each file.

Here's what the “Get shareable link” screen looks like. Click copy link and then you can share the folder with anyone else on your trip.

CalTopo pro tip: elevation profiles

An “elevation profile” is a sort of sideways look at your route, showing distance and elevation gain on a graph. It's a very handy tool to study your route, and making one with the great mapping software Caltopo takes just a couple of clicks.

If you're new to CalTopo mapping software and want to learn the basics, start with this video

CalTopo elevation profile example

Knowing the distance and elevation gain on a hike, bike ride or climb is really helpful. This is known as an “elevation profile” because it shows your route in sort of a side view graph, typically with vertical gain on the left axis and distance on the bottom axis.

In the pre-computer days, this was a very tedious task, involving counting contour lines through a magnifying glass, and measuring distance with a ruler. It was such a hassle that no one except true map geeks ever bothered to do it! However, in these modern times, making an elevation profile with with great mapping software like CalTopo is easy, if you know where to click.

For this example, let’s use a hike / climb of Broken Top, a popular climb in central Oregon. (Or, if you like, you can use any hike you already know.)

Go to caltopo.com and zoom into your area of interest. The default map layer, called “MapBuilder Topo”, is a good place to start.

First, you need a line on your map of your route.

If you know where the trail(s) or route goes, you can draw the line yourself. Right click, choose “New” > “Line”. Click on your starting point, usually the trailhead. You can draw line segments in three ways.

Draw short line segments with a series of clicks.

Draw a freehand line by tapping the control, shift or command key and click / drag.

Snap to an existing trail, shown in yellow highlights. (Sometimes the snap to function is handy, sometimes it's a hassle. You can turn this snap function on / off by selecting “Snap To > None” from the dropdown menu in the top right corner.)

Play around with these for a while to see how they work. Double click to finish your line. To delete a line you don’t like, mouse over it, right click, and select “Delete”.

Note: Don't be too concerned if the line you draw is not EXACTLY on your trail or route. You're not a professional surveyor here, you're just trying to get a general idea of the distance and elevation, so being super accurate is not usually so important.

Also, keep in mind that any estimated distance and/or elevation derived from a computer is always going to be a little different than the real world. The guidebook says that a hike is 10 miles and 3,000 vertical feet, But when you drawn an elevation profile in CalTopo it says it's 10.5 miles and 3400 vertical feet. And, when you hike it with your GPS recording a track, the track show something different. Which one is right? Dunno. How can you tell? You can’t. Does it matter? Probably not. Don't get too hung up on the exact numbers, this is for general estimation and planning purposes.

If you made a line with a series of short line segments, you can move the line a bit to make it more accurate. Mouse over the line, right click, and choose edit. The line should redraw with a series of small white dots. You can click and drag these dots to move that portion of the line. Play around with us to get a feel for it.

You can also make an elevation profile with an imported GPX track file. If you don’t know where your route goes, this is a good approach. On AlpineSavvy you can find tracks for more than 70 of the most popular climbing routes in the Pacific Northwest. For other mountaineering objectives, you can try Peakbagger.com, or some other local website with hiking tracks, such as oregonhikers.org. Sometimes a Google search for “Hikename GPX track” can get you what you need.

For our Broken Top example, when you’ve drawn your route, it should look something like this. (A solid red line is the default.)

After you’ve drawn your route, look on the left side of your screen. Under “Lines and Polygons”, you should see a red line with an “N/A”: after it. This is the line you just drew.

To the right of this, you should see three small icons. The first one looks like a little graph, the second one is a little pencil, the third one is a red X. Give each of these a click and see what happens.

The red “X” is delete.

The “pencil” icon is edit. Here you can add a name for your line, change the color, line style, or line weight. (In the photo below, I changed my line color to purple and increased the line weight a little bit. This is also a good time to add a descriptive name to the trail, such as “Broken Top climb”.)

Finally, clicking the “graph” icon should give you an elevation profile of your route.

If you move your cursor over the elevation profile on the bottom, you should see a corresponding red dot on the map in the upper part of your screen, showing your map location. Pretty cool!

Here’s an extra feature of elevation profile. On the top right of the elevation profile, you should see a small button that’s labeled “expand”. If you click this, you’ll get even a more detailed elevation profile. This shows a few extra whistles and bells like amount of forest cover, slope and aspect of the route, and more.

Looking at the slope coloration along the bottom edge of the line graph, we can see that it's a fairly flat approach up until about the last mile or so. That's about what you’d expect from a climbing route.

This is a lot of words to explain a pretty simple process. Try it a few times and you’ll pick it up quickly.

And yes, CalTopo is terrific. Please consider a modest annual subscription (starting at $20) to support continued use of this great tool.

Click the “Upgrade” menu along the top of the CalTopo screen to see various subscription options.

Weather forecasts made beautiful - Windy.com

Weather forecasts don't have to be boring. Windy.com shows you worldwide weather patterns at a glance, and also gives pinpoint local forecasts that are easy on the eyes. (Works on mobile devices and shows webcams, too, take that, mountain-forecast!)

Windy.com is a mesmerizing way to look at worldwide weather patterns. But, if you can make it past looking at Pacific Ocean wind patterns and dreaming of your next round-the-world sailboat trip, or checking out the typhoon in Sri Lanka, it's pretty darn good for local forecasts also.

What’s cool about windy.com?

Accurate and comprehensive forecasts (better than other sites like mountain-forecast.com)

It has a solid mobile app

No advertising

Local webcams, for an immediate look at road conditions

Here’s how to get a local forecast with Windy.com. (It works pretty much the same on your phone.)

Zoom into your general area of interest. (or use the search box in the top left.) Today, we’re after a forecast of Mt. Hood Oregon. Your screen should look something like this.

Next, click the three horizontal lines, (aka. the “hamburger”) then click “Settings”. On a phone tap the hamburger icon in the bottom right and scroll down.

Toggle the settings to your preferred measurement flavor, metric or ‘Merican. Here, everything is set to ‘Merican units.

Next, zoom in a bit more with either the scroll wheel on your mouse or the “plus” button in the top right corner. The map should change to be a lot more legible. Pan the map until the area where you want the forecast is visible.

Now right click (or long touch your phone screen) and choose “Forecast for this location”. On the bottom of the screen, you should get a nice multi day forecast for the exact spot you clicked. Be sure the “Basic” forecast button in the lower left of the screen is selected. Check out the other options on the bottom row if you want to get fancy.

A somewhat hidden but very useful feature of Windy is the “Compare forecasts” button on the bottom.

Click that, and see several different forecasts for the same location at a glance. Cool! Do they all line up more or less? Then that is a pretty good consensus. Is there a lot of divergence? Then the forecast is probably more questionable.

One more helpful feature - “Click for webcams”. Click this and it will show the available web cams that are on the map, that can be pretty darn handy.

Ranger-written "route guides" for Rainier

The Mt. Rainier climbing rangers have written an excellent series of guides for the most popular routes. which have a lot more detail and quality than you might expect. Definitely recommended reading if you are planning a Rainier climb.

The hard-working and highly skilled climbing rangers at Mt. Rainier National Park maintain a great blog on current route conditions.

Now, they've taken things a step further, writing essentially mini guidebooks on four of the most popular routes - Disappointment Cleaver, the Emmons-Winthrop Glacier, the Kautz Glacier, and the Liberty Ridge routes. They have the somewhat pedestrian name of “In Depth Route Descriptions”, and each one is between 20 and 30 pages.

Every climber attempting one of these Rainier routes will benefit by having a close look at these documents.

(And, in case the National Park Service ever decides to take down these route guides, I downloaded the PDFs, save them to a Google Drive, and you can see the same files here as well.)

Now, to be honest, my expectations for these descriptions were pretty low before I started to read them. We’ve all seen the plain vanilla climbing advice from government entities before, “Be sure you have adequate fitness, take the 10 essentials, leave no trace”, blah blah blah. But, I was pleasantly surprised at the level of quality writing and helpful information in these descriptions.

You’ll see:

detailed climbing and weather stats

case histories of Search and Rescue (SAR) missions

very detailed route descriptions

gear list

and great graphics! Here are a few examples from the Disappointment Cleaver route description.

All images below are from: http://mountrainierclimbing.blogspot.com/2017/03/in-depth-route-descriptions.html

How about a three-year average of weekly distribution of climbers?

Or maybe a chart of average and extreme summit temperatures during climbing season?

or maybe a “go, no-go” decision matrix, a more objective way to make choices on the mountain:

You get the idea. Lots of solid information that will be a real benefit to most climbers. Check it out, and be thankful for the professional Rainier climbing rangers that are trying to help you have the best trip possible.

Wilderness trip planning, start to finish (video)

There are some fantastic navigation resources online, but it can be confusing how to use them most effectively and where to get started. Watch this video to see one way to plan a climb, from start to finish.

There are a bounty of amazing navigation resources available to the backcountry traveler. Generally, this is a good thing, but it can also be a little overwhelming. What app to use? Where do I start? How do I print free maps? And maybe more specific questions, like:

I found three different GPS tracks for the trip I want to go on, which one should I use?

How can I make a map with the GPS track printed on it?

How can I get the GPS track into Google earth to scope out my route before I leave home?

What's the best way to get the GPS track onto my phone so I can use it with Gaia GPS?

I don't have a track file, but I have a pretty good Idea of where I want to go. How can I draw this track in on a map, print it, and get it onto my GPS?

If you’ve ever found yourself scratching your head with questions like that, we've got you covered with the video below. It covers most every aspect of wilderness trip planning - searching online to find a GPS track for a climb, opening and editing the track in Caltopo, exporting and opening in Google Earth, printing the map, and exporting the GPX file to your phone.

(Hint, parts of the video are best viewed in full screen.)

Real time snow depth map of USA and Canada

Want to know the amount of snow on the ground anywhere in the US and most of Canada? This is your go-to website. This interactive map from the US Forest Service is easy to use, understand, and shows real-time snow info for your trip planning.

When planning a backcountry trip (or even a long winter drive) it can be very helpful to know real time snow levels. Is the trailhead snowed in? Should I bring skis? Should I prepare for camping on snow, or bare ground? I heard it's really dumping in Utah, how much snow do they have? Is driving on the interstate across Wyoming in January going to be a bad idea?

The US Forest Service had you covered, with a very cool snow depth model (repeat, MODEL).

From USFS: “This map displays current snow depth according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Snow Analyses (NSA). The NSA are based on modeled snowpack characteristics that are updated each day using all operationally available ground, airborne, and satellite observations of snow water equivalent, snow depth, and snow cover. “

A few notes:

Works better on a desktop with a nice big screen.

Seems to default to dark mode on the map; if you want normal view click on the map icon on the left.

Possible software bug note: Apparently the USFS server will stop serving you snow depth tiles if you request too many of them, lame . . . If you pan and zoom a lot, the colored snow depth information may disappear from your map. So, try to stay in one area. Or maybe change to a new browser.

Government websites have an annoying habit of regularly changing URLs and breaking links. If the button below doesn’t work, do a web search for “USFS snow depth map.”

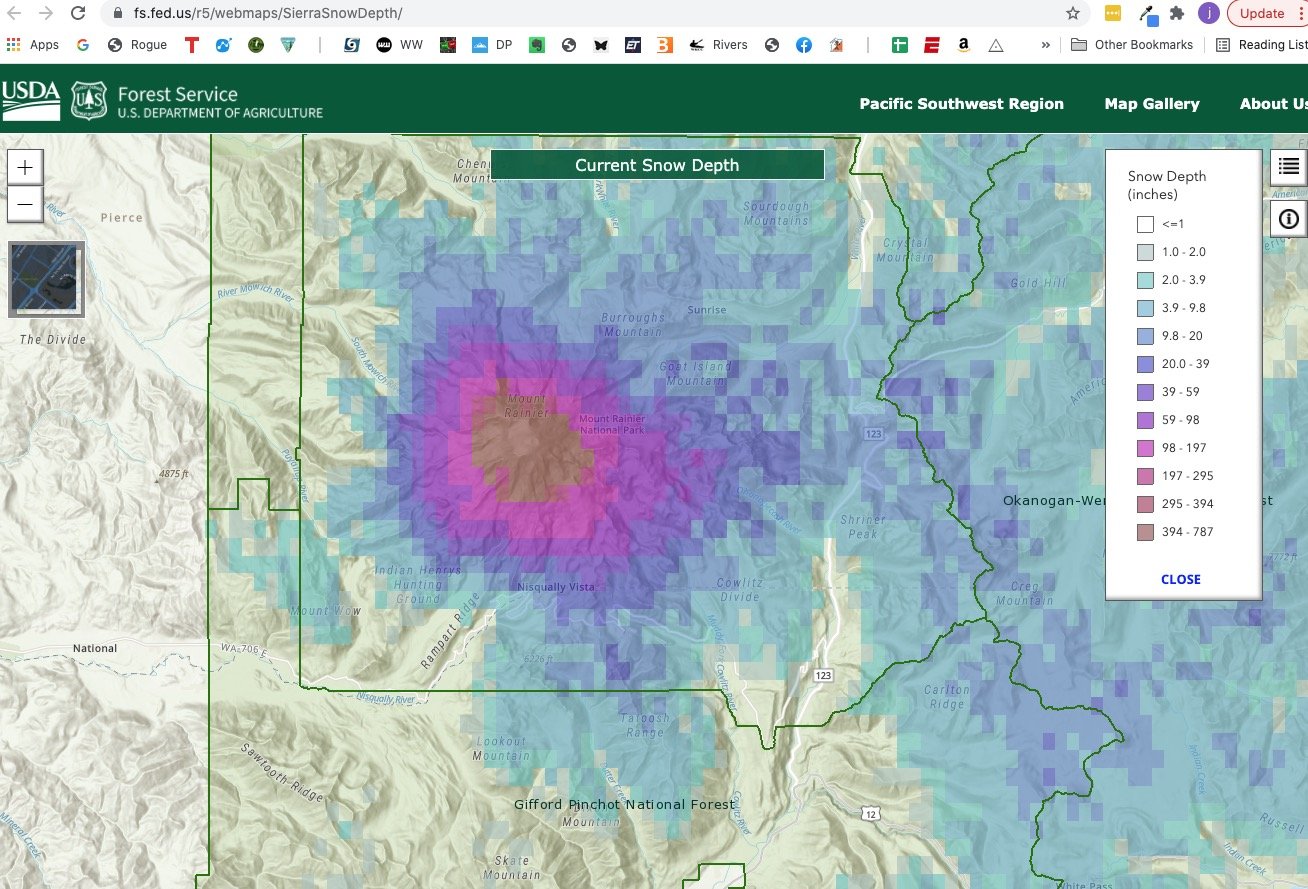

Here’s a screen grab - Mt. Rainier National Park, November 2021

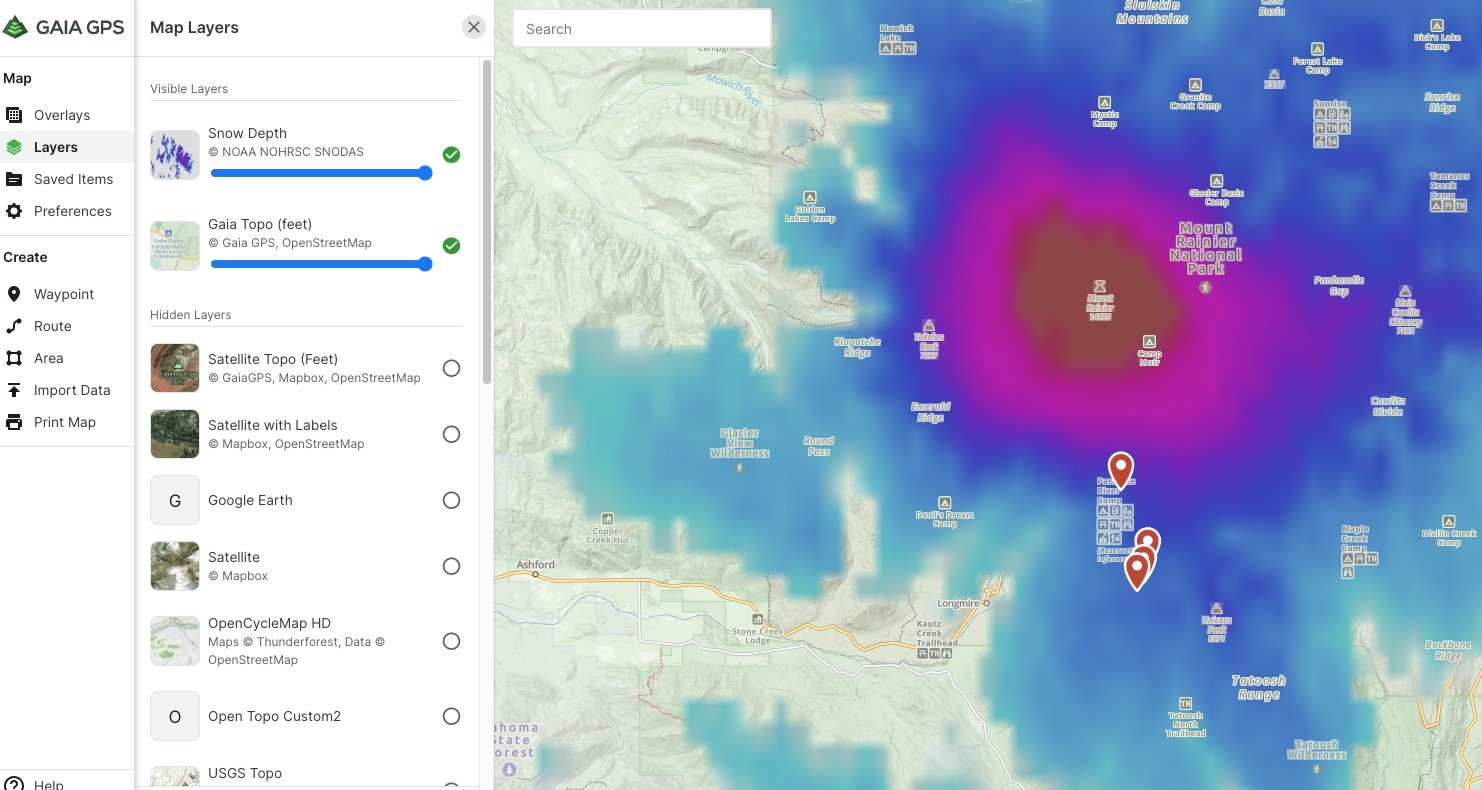

If you're a Premium subscriber to Gaia GPS, you can also get the same data in a more usable format. Gaia lets you change the opacity of various map layers, showing details of whatever base map you choose. You can also have a GPX track of your intended route on your map, so you can more clearly see whether your planned trip involves lots of snow or not.

Here's a screen grab of the snow depth data laid over the top of the Gaia Topo default map layer. Note the slider bar on the left, opacity is at 100%. Yes, it looks a bit hideous, but you can clearly see exactly where the snow begins.

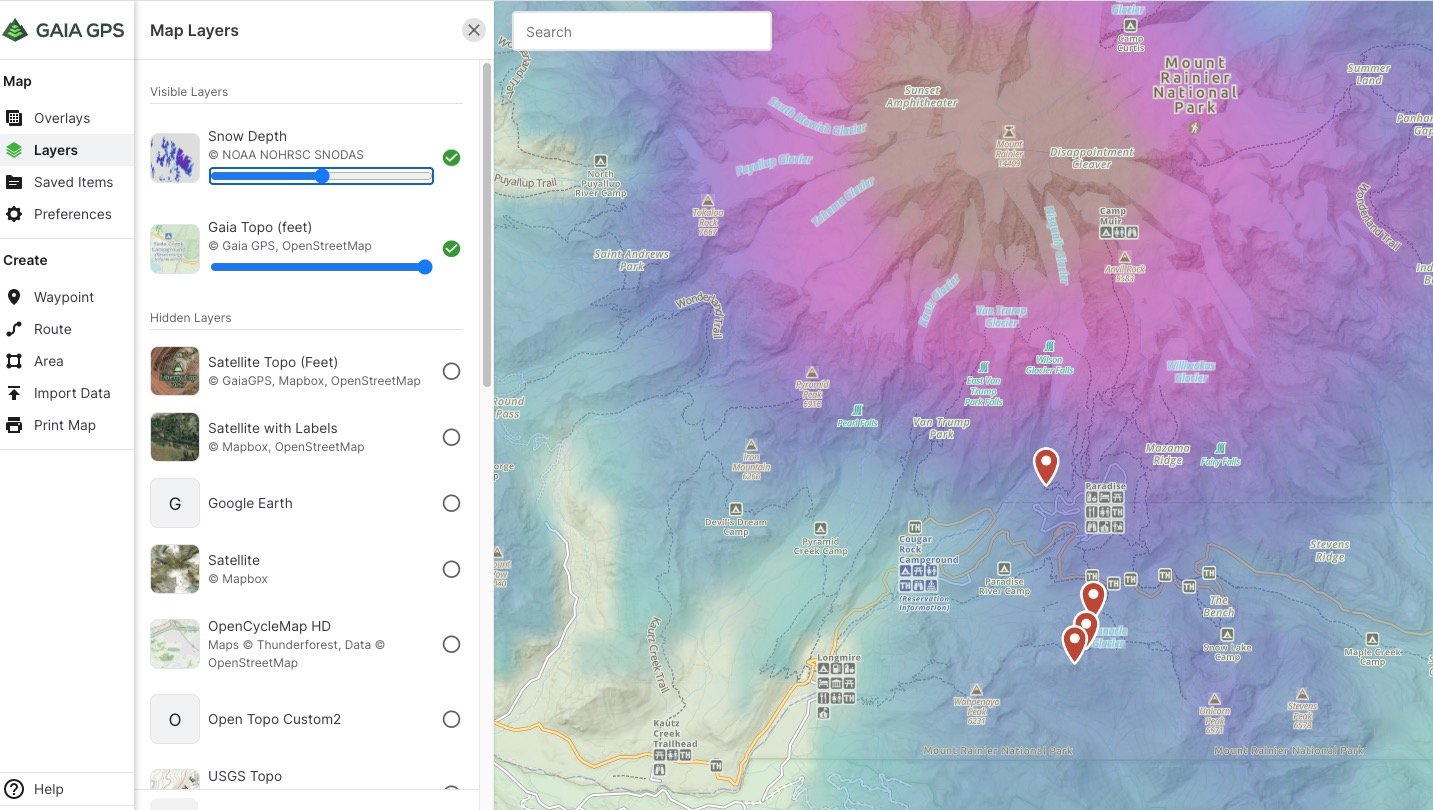

Now we've zoomed in a bit, and changed the snow depth slider bar to around 50%. Now you can see underlying roads and trails. A bit more helpful if you want to do some hiking.

CalTopo pro tip - stacking map layers

A slick, lesser-known trick in CalTopo is stacking various map layers onto each other to highlight unique map features. Learn how to do it.

(If you want to learn the basics of using CalTopo, start with this tutorial video.)

If you’ve spent any time around the navigation department of Alpinesavvy, you know I’m a huge fan of CalTopo.

Here’s a lesser-known CalTopo ninja trick you may find helpful - stacking map layers.

In CalTopo, you can stack two or more map layers together on the screen, and then with a slider bar or typed in percentage, change the opacity of each layer. (If you've ever used photo editing software like Photoshop, you're probably familiar with this idea.)

Stacking allows you to see features of interest in two different map layers at the same time. I rarely view more than two map layers at the same time, and definitely not more than three, otherwise you’re going to go cross-eyed trying to find the view you want.

Procedure:

From the main screen at caltopo.com, zoom to your area of interest.

Mouse over the map layer in the top right corner, and choose “Stack New Layer”

Choose a second map layer from the drop down to lay over the first one.

Let’s start with a satellite image base layer, for land cover, and overlay it with Open Cycle, which shows trails. Let's set the opacity of the Open Cycle later to 60%. You can do that with the slider bar, or by typing the percentage directly in the box as seen below.

In the screen grab below, we see the south side of Mount Saint Helens. You can clearly see which trails are in forest cover and which are not.

Let’s try a combination of satellite view, showing crevasses, stacked with slope angle shading, showing steep areas and possible avalanche terrain.

The settings for that from the top right corner would look like this:

Here’s the SE side of Mt. Hood. You can see crevasses and areas of steep, moderate and low slope angle. This could help you create a route that avoids crevasses and stays off of steep terrain.

With both of these on the screen, you can draw a line that hopefully avoids most of both. In CalTopo, right click, choose “New > Line”, then hold shift, and click and drag draw a freeform line.

You can then export this line as a GPX file for use in actual navigation in the field.

I think you get the idea. Dive in and play around with this.

And, if you find it worthwhile, I strongly encourage you to support CalTopo with an annual subscription of just $20 a year. Doing this helps ensure this great software continue to be available for us all to enjoy.

CalTopo pro tip - slope angle shading

“Slope angle shading” is a bit of cartographic wizardry that adds an overlay of color coded slope angle to a base map. It’s a handy tool for route planning, avalanche avoidance, and even sniffing out waterfalls. Learn how to use it in CalTopo.

If you're new to using CalTopo mapping software, watch this video tutorial to get started.

Note: this type of slope shading is made with an elevation model that may not show all relevant features and potentially hazardous avalanche slopes. It can be a useful tool for macro level trip planning, but is not accurate enough to completely assess potential avalanche hazard across all types of terrain.

Say you’re planning a canyoneering trip, climb, backcountry ski tour, or snowshoe trip.

Canyoneers want to locate possible waterfalls.

Climbers and skiers want to (hopefully) avoid potential avalanche slopes.

If you’re a good skier, you want to find a long run that’s reasonably steep but not ridiculous.

If you're on a long cross country hiking or climbing trip, you want to generally choose the path of least resistance and lowest angle slopes.

Good news, the best backcountry mapping software CalTopo has you covered.

Zoom into your favorite mountain area, and choose a base map.

Mouse over the map layer box in the top right corner, and click the drop-down next to Base Layer. I think the default map layer is MapBuilder Topo. This is my go-to map layer and a fine place to start, because it shows topography, contours, updated trails, and shaded relief.

Just under that you'll see some checkboxes in the category “Map Overlays”.

Check the box next to “Slope Angle Shading”, as seen below.

You should then see a color coded overlay added to your base map, showing approximate slope angle.

Yellow > orange, 27 to 35 degrees, low angle and pretty mellow, probably safe to travel on.

Red > purple > blue > black is 35 t o 60+ degrees, progressively steeper and possible avalanche terrain.

You can print this out, draw in a track of your intended route or import a GPX track you already have.

Canyoneers or photographers, looking for secret waterfalls? Find a stream drainage that goes over an area of blue/black. That's likely going to be a waterfall.

Here’s a view of the north side of Mt. Hood, with the Forest Service base map. Note the marked waterfalls on the map, that correspond with the stream running over an area of blue/black shading.

Here are a few more screen grabs.

Mt. Adams

Mt. Rainier

Snow telemetry for winter trip planning

“Sno-Tel” data stations show real time weather data for hundreds of mountain locations, including snow depth, recent snowfall, and min/max temperatures.

Snow telemetry, or “SNOTEL”, is a system of snowpack data monitoring stations around the western USA. They offer real time snowpack data for a specific location. If you’re planning a trip in the general area at around that same elevation, you can probably expect to see about that same level of snow.

Below are some screenshots from showing how you can get started.

(Note that some of the screenshots are a year or two old, and the current website might look a little different.)

If you want to see snowpack models for the whole Western USA that are made from these data, you can learn about those here.

SnoTel stations in the Western USA (from CalTopo.com > Realtime Data)

From here, you can zoom in on one particular area of interest. For this example, we’ll look at the south side of Mt. Hood Oregon.

Above each small circle, if you squint a bit you can see three numbers. The top is the current snow depth in inches, the middle is the “snow water equivalent” (not of much interest to most backcountry users) and the bottom is the current temperature.

If you click on the red circle, you get a pop up graph of basic data from the previous seven days. If you want to take a deeper dive into the data, click on the “Official Site” link in the graph.

That brings up a page that looks something like this:

From here, you can look at all sorts of tables and graphs of past data. What has the snow depth and temperature variation been over the previous month? Was there a freeze thaw cycle, which might solidify the snow pack? You can view the data in a table or a graph. Choose what flavor of data you want to view, use the “Layout” drop-down to select a chart, use the “Time Period” drop-down to select dates you want to see, such as previous 30 days.

(Some of the charts shown below are from a year or so ago. The website is re-formatted regularly and what you see may not quite look like this.)

Table of recent snow data. See snow depth and air temperature. Can show at a glance if there’s a freeze/thaw cycle.

and a graph. The red line shows exact snow depth at that location.

In Feb 2021, Gaia GPS added a snow telemetry map layer as well, available for premium level membership. They are layer is a bit more user-friendly, because it has some color coding to show whether snow is melting or accumulating. Here's a screen grab of that, with the legend added to the lower left corner.

And zoomed out a bit . . .

Emergency contact info - what you need to share

Sometimes in the rush to leave the house, we may forget to leave important information with our emergency contact person. Take a few extra minutes and do it right.

When you head out for a climb, it’s good practice to let a responsible someone know ALL the details of your trip.

In the last minute rush to leave, all that might get said is, “Going to Rainier, back on Tuesday!”

A more detailed written notice you leave with a person not going on your trip might include:

Destination - peak to be climbed, trail to be hiked

General route you plan to take

Campsites - if overnight, list campsite location(s) for each night

Names of climbing partners, and names and phone numbers for their emergency contacts

Times: Hike / climb will leave the trailhead/base camp at ________ a.m. / p.m. on _______________ (date), Planned return to trailhead/base camp ______ a.m. / p.m. on _______________ (date)

Make and license of car(s) your team will drive

Trailhead where car(s) will be parked

Bivy gear (stove, tent/bivy bag, sleeping bag, food for # days) the team will carry

List of communications gear (cell phone, satellite com device, GPS) the team will carry

Emergency phone numbers for the climb area (usually Nat Forest District Office, County Sheriff or Nat Park Service)

Important: Estimated time off the peak. Consider a “yellow-red” system of times: “We plan to call to check in with you by 4:00 pm. If you don’t hear from us by 9:00 pm, call the sheriff”.

Here's an important tip on what NOT to do.

With the growing popularity of satellite communication devices such as the Garmin Inreach, many people like to check in with concerned people at home and let them know everything is OK.

Doing this is fine, but do NOT let a lack of check in become the basis for a rescue.

If your satcom device breaks, gets lost, or runs out of batteries, and you are fine, the last thing you want is to trigger an unnecessary “rescue” because you did not do your evening check in with your spouse or partner. You should make it clear before you leave home that lack of communication does not indicate a problem.

See the Exact Right Spot with lat/long coordinates on Google

Google maps and driving directions works great in the city, where places have street addresses. But what do you do in the backcountry? Answer: use latitude longitude coordinates in decimal degrees, to pinpoint any spot in the world and (usually) get driving directions to it.

Most of us have suffered through trying to follow well-meaning but wildly confusing directions to get to a remote trailhead or campsite on obscure fire / logging roads.

The directions usually look something like: “Turn off the main road, then go to .7 miles on Forest Road 1234. At the 3-way fork, take the middle fork on road 1234-10, then go 3.2 miles on that, and then . . . ” You get the idea. And if any new roads have been added or removed since the guidebook got printed, or some local yahoos have been shooting up the road signs so you can’t read them, then things REALLY get confusing!

Here’s a superior system for giving a precise location, and ideally directions, to most anywhere that doesn’t have an actual street address. Which is most of the fun places we want to go play, right?

If you type latitude longitude coordinates (preferably in decimal degree format) into a Google search or a smartphone mapping app, it places a marker directly on the spot. You can then get driving directions to it.

Try it! Here’s the lat long coordinates in decimal degree format for the Mt. Thielsen trailhead in southern Oregon:

43.1459, -122.1277

(If there are any guide book authors reading this, can you please please please start using latitude longitude decimal degree corners to describe Important Places in your book?)

Note:

- Use a comma between the latitude and the longitude.

- Be sure to include the “minus” sign before the longitude. This indicating west longitude rather than east. If your intended map of the Pacific NW instead draws in China, then you probably skipped the minus sign. =^)

Note the number of decimal places. In this example, we are using four. If you use less than four decimal places, Google doesn’t recognize it as a coordinate and thinks it’s some kind of a math problem.

Four decimal places gives you positional accuracy down to about 3 meters. We’re not measuring property boundaries here, so for things like finding your tent in the woods or locating a trailhead, four decimal places is fine. If you use a GPS app on your phone, you may see a coordinate of six or even seven decimal places. This is theoretically accurate down to sub 1 meter, but that’s a little deceiving because the GPS chip on your phone is not that good. When I get a six digit coordinate from my phone or mapping app, I usually just remove the last two digits until I get down to four decimal places. That is simpler and easier to transmit and write down.

You can get decimal degree coordinates in several ways.

Probably the easiest is to go to Google maps and zoom in on your area of interest. Right-click, and choose “What’s here?” This opens a pop up box. The latitude longitude coordinates in decimal degrees, of the exact point you clicked, appear at the bottom of the box. Copy and paste the coordinates into a new Google search to test. If it draws your spot correctly, your coordinates are correct.

Go to caltopo.com, the best online mapping software. Using the different map layers from the upper right corner, choose one that lets you zoom in to your area of interest. The coordinates of the cursor are shown in the upper right corner. Change the coordinate type to “Degrees” from the “Config” menu at the top of the page. Also, you can right click and choose “New > Marker”, and you should get a pop-up box with the location of the coordinates, which you can then copy and paste.

Note:

- UTM coordinates, the preferred coordinate system for backcountry navigation with map and compass, are NOT recognized by a Google search.

- Latitude longitude coordinates in the traditional degrees minutes and seconds and the more specialized format called degree minutes ARE recognized with a Google search, but these are harder to obtain and it’s easy to screw them up when you enter the coordinates. (The “degree minutes” system is typically used by electronic navigation systems in ships and airplanes, and usually not much by civilians.) So, it’s usually best to stick with decimal degrees as shown above.

Other examples of coordinate systems, all showing the same location, the Mt Thielsen trailhead:

UTM: 10T 570913E 4777387N

Latitude longitude, degrees minutes and seconds: 43°08’46”, -122°07’41”

Latitude longitude, degree minutes: 43°08.76’, -122°07.68’