Alpine Tips

9 phone apps for wilderness navigation

There are lots of handy tools you can keep on your phone to help with wilderness navigation. Here are some of my favorites. Better yet, pretty much all of them are free and weigh 0.0 grams!

There are lots of handy tools you can keep on your phone to help stay found. Here are some of my favorites.

Better yet, pretty much all of them are free and weigh 0.00 grams! (This is geared toward iPhone, ‘cuz that’s what I have.)

In rough order of importance:

GPS - GaiaGPS, Caltopo and Fatmap are all popular options. Find one, learn it. Cost, about $20 a year.

Compass - The iPhone has a great built-in compass. Cost, free.

Altimeter -There are lots of altimeter apps. Cost, free.

Photos - Take photos of guidebook pages. Download a photo of a redlined route, save it to your phone. Take photos of your route when climbing, red line or annotate. Save Google Earth screengrabs. Cost, free.

Kindle / pdf reader - Save a PDF of a map. Download an entire guidebook (or wilderness first aid book!) as an e-book. Cost, free.

Inclinometer - The iPhone has a handy inclinometer, under the “Measure” tool. Great for assessing avalanche potential and bragging to your friends about how steep your ski slope was.

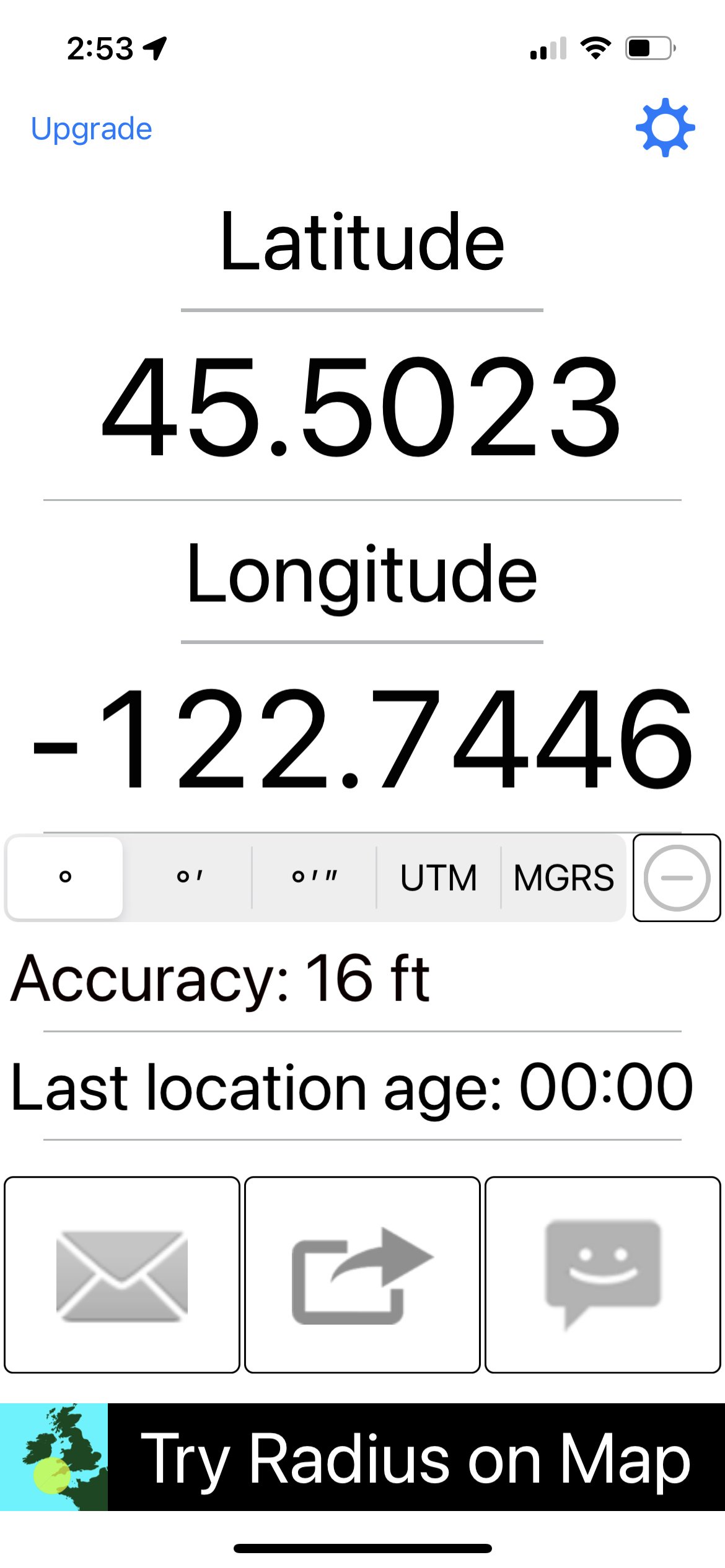

Show & share my coordinates - clearly display your coordinates, email or text them along with a message. Extremely helpful to show your exact location if you have a backcountry emergency and a cell connection. This is one of several ways to get coordinates from your phone. This app is called “My GPS Coordinates”. Cost, free.

Barometer - Newer phones have barometric pressure sensors. Rising or falling barometric pressure can indicate a potential change in weather. Cost, free.

GPS Diagnostics - kind of nerdy, but occasionally useful. If your GPS is acting up, you can use this to see the quality of your satellite connectivity. Cost, free

GaiaGPS

Compass

Altimeter

Photos

Screen grab from web, Google Earth screen grab, guidebook photo

Kindle / Book reading app / PDF reader

Make a PDF map in CalTopo. Email it to yourself or AirDrop to your phone. Save in Books or Kindle.

Inclinometer

Show & share my coordinates

(Tip - you only need 4 decimal places.)

Barometer

GPS Diagnostics

GPS bearings: a modern way to navigate

You want to hike off trail to reach a lake. While you could measure the bearing from your (hopefully known) location to the lake and follow it if you have a map and compass, or get out your phone and stare at your screen for a mile or so, consider a hybrid method: the GPS bearing. Get the distance and bearing from your phone, and follow your compass to your objective.

While folks have been using this concept for a while, I was introduced to this idea from Steve McClure of the Seattle Mountaineers, a navigation expert and editor of the classic mountaineering textbook, “Freedom of the Hills”.

The takeaway: GPS is great for identifying your exact location. It’s not so great, by itself, for following a complex off-trail route. Instead, use your compass along with your GPS. Drop waypoints along your route at important junctions, use a GPS app to get distance and bearing to the waypoint, and then follow that bearing with your compass.

You’re at a lake, which you can locate on your map. On your map, you see another lake that's about a mile away towards the north / northwest, with no trail to it. You want to go camp there for the night.

You have several navigation options.

Map and compass: Get out your map and compass. Put either long edge of your (declination adjusted) compass baseplate between your location and the lake, then rotate the compass dial until north on the compass points to the north/top of your map. This should show you the bearing between your location and the lake. Pick up the compass, hold it flat in front of you, rotate your body and compass until the magnetic needle matches the orienteering arrow. You should be facing the lake; start walking. Hopefully there aren't any cliffs, thick vegetation, rabid marmots, or other obstacles between you and the lake. (Learn how to do this here.)

Phone only: Using your preferred navigation app, add a waypoint at the lake you want to go to. Use the “Guide Me” (or similar) function, which tells you the distance and bearing from your location to the lake. Start walking, holding the phone in front of you pretty much all the time, using the directional arrow in your navigation app to walk you to the lake.

Both methods can work, but they have some problems.

With the map and compass, you need to have a printed map, a compass, and know how to use them together. It can take a little time, can be tricky to do if the weather is not cooperating, and if you do it wrong you can introduce large errors, some even as big as 180° if your compass is backwards. (You also have to be able to find your current location on the map. If you're completely lost, this doesn't work.)

With only the phone, you decrease your awareness of the terrain around you, because you're doing “heads-down” navigation, staring at your phone screen the whole time. Plus, you’re draining your phone battery unnecessarily by leaving the screen on.

Instead, try a hybrid method: the “GPS bearing”.

Rather than measuring a bearing between your location and the lake with the old school map and compass method, you get the distance and bearing from your navigation app, and then use your compass to follow it.

Pretty much every quality backcountry navigation app has some function to tell you the distance and bearing from your current location to another point on the map. As I write this, in autumn 2021, using Gaia GPS, you can simply tap the screen. That brings up a pop-up window that says “Marked Location”, and tells you the elevation, distance, bearing and coordinates of the spot you touched. If you have a saved waypoint you're trying to navigate towards, you can use the same technique. Tap the waypoint and see the distance and bearing in the “Marked Location” pop up box.

Now, instead of staring at your phone and following the line and arrow to get to your destination, you dial your compass to that bearing.

In the photo at the top of the page, your phone tells you it's 347° from your location to the lake. Rotate your compass dial to 347. Hold the compass flat in front of you, with the direction of travel arrow pointing away from you. Rotate your body and the compass until the magnetic needle matches the orienteering arrow. Schweeet, you’re now facing the lake. (Learn how to do this here.)

Turn off your phone screen, put your phone away, and start walking towards the lake. No need to be religious about staying exactly on a compass bearing; walking in the general direction is usually fine. Adjust your route as necessary to get around obstacles. Have a quick look at your compass every few minutes to be sure you're more or less continuing in the right direction.

After 10 minutes or so, take your phone out, and simply repeat the process: tap on your objective, and get a new distance and bearing follow it. The distance should decrease as you approach your objective. The bearing will change a bit, depending on how much meandering you’ve done since you started. Change your compass dial to that new bearing, put your phone away, and keep on walking.

You’re saving your phone battery, and you're navigating “heads-up” with much greater awareness of the terrain.

The old school “follow-a-compass-bearing-on-a-straight line” method can work okay if the terrain is open and doesn’t have any obstacles, but that's not going to happen much in the mountains. That's the beauty of the GPS bearing. You don't have to focus on staying on the single compass bearing; you can choose the route that makes the most sense, occasionally repeating the process of getting a new distance and bearing, and making small adjustments to your course as needed.

Another significant advantage of using GPS bearings is that you don’t need to know your current location on the map for it to work - that's a major drawback of the map and compass method.

Even if you use GPS phone app and compass, it's still an excellent idea to bring along a paper map. If your partner also has a phone GPS app, a fully charged battery to start the trip, and a back up battery with charging cable, that's a pretty good redundant system. Yes, phone batteries can die, but maps can also blow away or be ruined by rainfall.

Let's be honest, if you have the choice between using a slide rule or a calculator to do some arithmetic, you're going to reach for the calculator every time. Yes it uses batteries, but it's also a superior tool. Same with the phone GPS. Combine it with a compass and you have the best of both worlds: always knowing your exact location and the direction of your next objective, maximum phone battery preservation, and better awareness of the terrain around you.

You don't necessarily need a compass to use this method. Good backcountry navigation phone apps like Gaia GPS and CalTopo have an indicator arrow that changes direction as you rotate your body, which can help point you toward your objective. However, using a base plate compass can still help you preserve battery, because you're not checking your phone as often.

The example above is pretty simple, going from one point to another in fairly open terrain for a short distance. We can use the same principle for a longer more complex trip, simply by adding additional waypoints. Here's an example of a ski circumnavigation of Mt. Hood.

The blue line shows the approximate route, which of course changes based on snow conditions, crevasses, etc. The red waypoints show some key decision points. Instead of trying to ski staring at the blue line and attempting to stay on top of it (which of course would be pretty ridiculous), instead focus on moving from waypoint to waypoint. If there is a bit of a detour, and it's not a straight line, such as between points 3 and 4, simply tap the screen on your phone on the track line to add an intermediate marker point, and navigate that to stay on course.

If you spring for the “Pro” level subscription for CalTopo, you get access to a very cool tool they call a Travel Plan. Draw in a route and add some waypoints like what you see above. Then you can generate a Travel Plan, basically a table showing (among other things) the distance, bearing, elevation gain or loss, and anticipated travel time between different legs of your trip. Below is one example.

I have a whole article on the Travel Plan function of CalTopo; you can read it here.

Backcountry GPS - map reading still required

A GPS device is an amazing backcountry navigation tool. But it still only gives you straight line bearing and distance to an objective, which is often not an option in the mountains. Augment your GPS with some basic contour reading skills to help you choose the best route.

map made from caltopo

We can get complacent when using GPS for city navigation, because the turn by turn directions are usually close to perfect. But in the backcountry, when your GPS only tells you distance and straight line bearing from one point to another, you often need to add some common sense and basic map reading. Let's look at an example.

You're camped at Lower Hopkins Lake and want to go to the unnamed lake. Using the Gaia GPS app on your phone (my favorite choice), you add a waypoint at the unnamed lake, and then use the “Guide Me” function to get distance and bearing from your current position.

Your phone tells you it’s about 2 miles and a bearing of 250 degrees from your camp to the lake.

Would it be a good idea to follow this bearing ? Why or why not?

A GPS bearing shows only the straight line distance and bearing between two points. It doesn't show what's necessarily a good route choice. Following a direct bearing of 260 degrees would get you into some steep terrain, shown by the contour lines on the hillside that are very close together.

A longer, but probably better route is the green line. It's less steep, which is shown on the map by contour lines that are a bit farther apart.

Do you need a printed map, or necessarily a compass, to get to the lake? Probably not. But the basic skills of reading contours can still come in handy, and even if a GPS device is the only navigation tool you carry. Following a direct line, especially in the mountains, is rarely the best choice.

Map by CalTopo, the best backcountry mapping software.

map made from caltopo

Want to learn the basics of how contour lines show real world terrain? Check out the video below.

A complete guide to CalTopo: training.caltopo.com

CalTopo, the best backcountry mapping software, now has a comprehensive and user-friendly training website that covers every aspect of this mapping tool. After you learn the basics from some YouTube videos or practicing on your own, go here to take a deeper dive.

CalTopo is the best backcountry mapping software currently available. You can probably figure out the basic functions by pecking around and by watching a short tutorial video like this one; (disclaimer, it's great and it's mine. =^)

However, like a lot of software, it has some powerful features that are not so obvious. Well, good news! As of Dec 2020, the CalTopo team launched an entirely new training website that shows you every nook and cranny of this great navigation tool.

I know this software pretty well, and I still learned several great new tips just in the first few minutes of working on this training website, such as better use of folders, creating a custom layer, and using the new feature Map Sheets.

Here's a screen grab from the CalTopo training homepage.

Here’s the scoop, direct from CalTopo:

“We are excited to share the first section of our new training website (training.caltopo.com) dedicated to using CalTopo, on the web, mobile app, and desktop. We began by creating an All Users section that expands significantly upon our existing knowledge base and aims to address the basics of every function in CalTopo.

We will continue to expand this training site to include additional sections aimed at both First Response and Recreational users of the program. Existing sections will remain up to date as we add new features and improvements.

This training site is our primary resource for all CalTopo questions. Whether you are entirely new to CalTopo or just looking for the details of a specific task or tool, you will find answers in the CalTopo training site. We welcome you to take a look at the site and see if you learn something new!”

GPS tracks: even better with waypoints

What's better than having a GPS track to help you stay on route? Having a route with waypoints added. This improves your situational awareness with “heads up” navigation, and minimizes time spent staring at your screen. (Saves phone battery too.)

A GPS track file can be a great help in the backcountry to help you stay on route. What’s even better? A track file with waypoints added. Why?

Because a GPS device (an app on your phone like Gaia GPS or a handheld GPS), can tell you distance and bearing between waypoints. This lets you break your trip down into a series of segments from one waypoint to another.

Use the “Guide Me” (or similar) function on your GPS to see the distance and bearing to the next waypoint. Then, set that bearing on your compass to get you started in the right direction, put your phone in your pocket to help save battery, and shift your attention “heads up” to the landscape around you, and away from your screen.

Compare this with a track without waypoints. Here, you don't have any distance and bearing between points, just a line on your screen. In more complicated terrain, or with low visibility, you may need to check your GPS every few minutes to see that you haven’t wandered too far left or right from the track. This runs down your battery, leads to “heads down” travel, and decreases your situational awareness by shifting your focus on your screen, and not the terrain.

One other benefit to adding waypoints, especially if you’re using our favorite desktop mapping software CalTopo, is with the Pro level subscription and up, you can easily make what CalTopo calls a “Trip Plan”. This is a very helpful table showing all of your waypoints, and the distance, elevation gain, and estimated travel time between each one. We cover this helpful tool and a lot more detail at this article.

Of course, some terrain is more suited to doing this than others. Traveling above timberline in an alpine setting is generally pretty easy, down lower in the trees maybe not.

Here's a screen grab of a CalTopo trip plan for a ski tour around Mt. Hood:

Shaded relief - helpful, and a fun optical illusion

Shaded relief, a.k.a. hill shading, is a cool cartographic trick that helps you see topographic maps in more 3-D. While it’s very helpful to see features like creek drainage and ridgelines, it also is a cool optical illusion - if you turn the map upside down, the creeks and ridges reverse! It's a better show than a tell; check out the examples in the article.

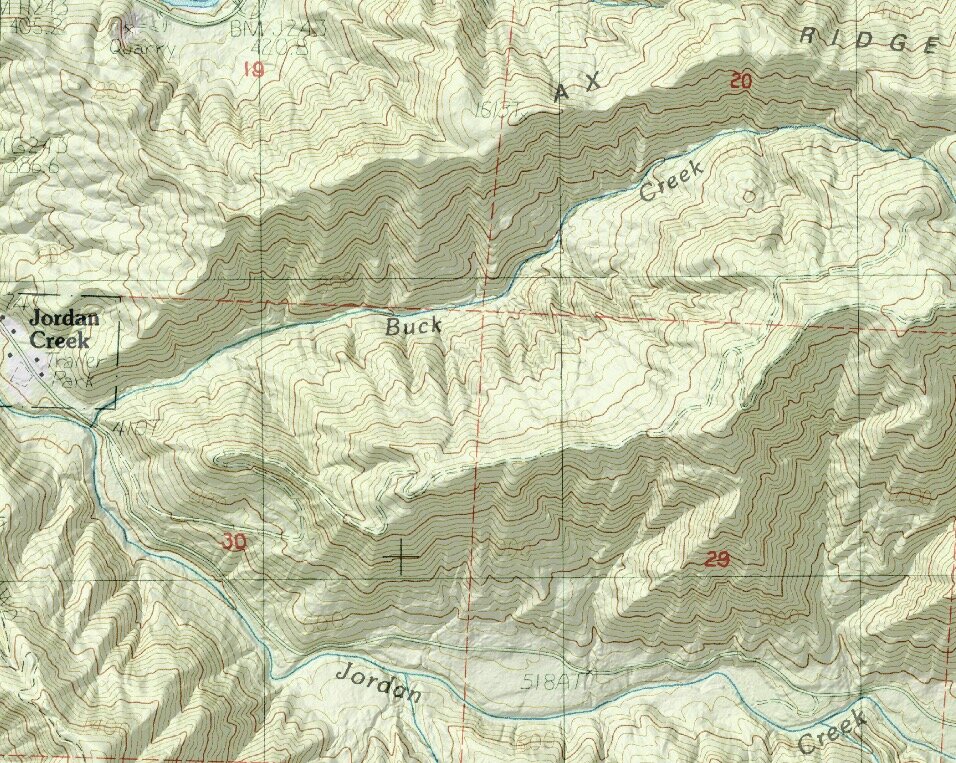

An ordinary topographic map can look like a big bunch of squiggles, and it takes practice to “read” the contour lines to make out landforms like ridges and gullies. A clever bit of cartographic wizardry known as “shaded relief” (aka hill shading, or terrain shading) tricks the brain into seeing terrain features such as ridges and gullies more in 3-D, extremely cool!

Here’s a side-by-side example of the exact same terrain. The top map is the standard topographic map, and the contour lines mostly look like a spaghetti pile. On the bottom is the same area with shaded relief added. You can clearly see the streams and ridgelines, nice!

So, here's the fun optical illusion part. If you turn the shaded relief map upside down . . . The streams appear to be ridges, and the ridges appear to be the drainages! Check out the map below. Jordan Creek and Buck Creek appear on a ridge . . . but you know creeks don't go on ridges! If you're seeing this on your phone, you can take a screenshot and turn it upside down also.

Pretty cool, no?

This does have some occasional practical use in the field. If you have a shaded relief map, and you rotate the map so south is at the bottom (called orienting the map, which you might do when walking south) be aware of this illusion, because what you see on the map might well trick your eye.

Some navigation experts claim that you should not use shaded relief at all because of this potential for error. I disagree. The huge increase in legibility for the average user is a massive benefit that far outweighs the potential eye trickery when you may occasionally view the map upside down.

You can create shaded relief maps like this for free from the great mapping website Caltopo.com. Lots of Caltopo is free, but for a modest $20 annual subscription you can access even more. If you love maps, please consider a subscription to support the creators of this very helpful mapping tool, hint hint.

Learn to use Caltopo from this YouTube video.

Printing backcountry maps in CalTopo

CalTopo is a top choice for backcountry mapping software for many reasons. One big one is the ease of printing. Let's have a closer look at some of the print features of CalTopo, some obvious and some a little more hidden.

CalTopo, my favorite backcountry mapping software, has a lot of great features. (While many of them are free, you can get a lot more with an annual subscription, which I strongly encourage you to do.)

One CalTopo highlight is superb map printing. Let's have a closer look.

1 - CalTopo generates a “geospatial” PDF

Rather than just spitting out a file to your printer, CalTopo generates a PDF file. (There is a JPG option, but I hardly ever use it.) This makes it easy to save the PDF to your computer, the cloud, and/or email it. This might sound like a trivial feature, but it's really handy. Tip - the “Generate PDF” button opens a new browser tab that shows the PDF. Remember to save or print this file; if you close the browser tab, it's gone and you have to generate it again. You can also save this PDF to your paid account, making it easy to share and organize.

Plus, it's not just a “dumb” PDF file, it's what's termed “geospatial”, or “geo-referenced”. This means that it has real world coordinates embedded in the file. This lets you to use the PDF map in various types of phone GPS apps, such as Avenza, as your base layer. (Personally this is not something I use, but some people find it handy.)

2 - Choose your paper size (depends on subscription level)

A free CalTopo account lets you print only on one paper size. But as you move up in subscription levels, it gives larger and larger printing options. At the basic $20 a year level, you can print on 11” by 17” paper, which is a very convenient size for lots of backcountry trips. By adjusting map scale to a custom number (such as using 1:30,000 rather than 1:25,000) and paper size, you can often print a map for a fairly large area on a single sheet of paper. (Pro and Desktop subscription levels allow printing on pretty much any size paper you want.)

3 - Print at any map scale you want

Many types of mapping software don't give you any option to choose the scale, and they don't tell you what scale the map is even when it does get printed. CalTopo does both. At the top left side of the print dialog box, there’s a dropdown for five or six common map scales. You can also choose your own, under “Custom”. (I often use this feature to make custom orienteering maps, which are often a 1:10,000 scale.)

4 - Choose your DPI (depends on subscription level)

DPI, or dots per square inch, determines the overall quality of your printed map. The default DPI is 200, which is fine for most weekend climbing and backpack trips. Higher subscription levels (Pro and Desktop) give you access to a 300 and 400 DPI option.

5 - Print a UTM or lat/long grid

Having a printed UTM grid on your map can be helpful for several things. It can help you estimate distance in kilometers, lets you plot UTM coordinates from a GPS onto your map, determine your UTM coordinates from your map, and give you a grid that's pretty closely aligned to true north, which can make measuring compass bearings on your map a bit more accurate. You can toggle this grid on or off with one click. I usually choose to have it on.

6 - Print multiple pages

One of the most powerful features in CalTopo is the ability to print multiple map pages, and do so in any combination of landscape or portrait that you want. For example, on a multi-day backpack trip you would probably need to print out several different pages to cover your trip at a reasonably large scale. If your trail runs north-south, you can print in portrait mode. If the trail changes to more east-west, you can print a few pages in landscape. Also, the red box that shows the actual print area is idiot proof and accurate. Click and drag the red print area boxes to determine how much overlap you have between map sheets.

7 - How to print it

Always protect a printed map from the elements. At the bare minimum, use a 1 gallon Ziploc freezer bag. Having the map in a plastic bag also makes it much more resistant to tearing.

It's best to print your map on a color laser printer if possible. Typically I save the map from my desktop computer onto a thumb drive, take the thumb drive to my local office store, and use the color laser printer there for a buck or two.

8 - Other helpful map information

On the bottom margin, CalTopo prints just enough info to be helpful, but not more than you need. You get a scale bar in miles and kilometers, the UTM zone, a ratio scale (like 1:25,000) the map datum (defaults to WGS84), and the correct magnetic declination for your location (declination is often incorrect on older printed maps).

One unique feature of CalTopo maps is a QR (Quick Read) code, printed on single page maps only. If you point your phone camera at the QR code, it can save the map as a PDF onto your phone, very cool! (You can even do this off of a computer screen, you don't even have to have the printed map in front of you.) This means one person can make a PDF map, email it to everyone else on the climbing team, and they then can print it, and/or save the map to the phone with the QR code. I'm a big fan of always carrying a digital backup of a paper map on my phone, and this is a super easy way to do it.

Here’s an example of the bottom of a CalTopo one page map, showing datum, UTM zone, two scale bars, ratio scale, QR code, and declination diagram.

Finally, here's an example of the finished product, for the Disappointment Cleaver route, Mount Rainier.

1:25,000 scale

11 x 17" paper (prints nicely on 1 page)

1 km UTM grid

MapBuilder Topo layer

Download maps for an entire state in Gaia GPS? Yes!

You can (probably) download maps covering an entire state (or small country) of the excellent “Gaia Topo” map layer in just a few minutes without maxing out your phone memory. This lets you ALWAYS have a great base map on your phone when outside of cell coverage.

With most every backcountry mapping phone app, a necessary but often tedious chore is downloading the map layer(s) covering your outing to your phone before you leave cell phone coverage. Sounds simple enough, right?

But, if you want multiple map layers, at different resolutions, and especially if your phone has limited memory (maybe even forcing you to select and delete previously saved maps, or deleting the memory cache of the app to free up memory), coordinating all this can become a serious hassle. And of course, how about those times when you forget to download maps, or change destinations, or drive an unexpected route home? Whoops, maybe you’ll have no map at all!

Happily, those days are pretty much over. There’s now a convergence of two great navigation advances: phones with lots more memory, and high quality map downloads that require less space. A great example of the latter is the new and greatly improved “Gaia Topo”, the default layer from Gaia GPS, my favorite backcountry GPS phone app.

Making plans for a Utah road trip, with great places to explore and lots of remote areas outside of cell coverage? Before, downloading high resolution maps for the entire state would've been pretty much impossible, because it would max out the memory on most phones, not to mention taking hours to download. But not any more! On wi-fi, the download only took me about 8 minutes and about 230 MB. (Or is it 443 MB? See below.)

You might think that decreasing the download size would also result in less useful map information. But, it's actually the opposite - the Gaia GPS cartography wizards somehow managed to make this map layer have MORE useful data, while at the same time making the download sizes much smaller.

How does Gaia fit so much data in such a tiny download? I don’t know all the details, but it’s pretty damn cool and I love it! (We could get into a nerdy discussion about raster versus vector map data, zoom levels and map scale, but that’s a little much for the non map-geeks.)

I cover the many improvements in the Gaia Topo layer in detail in this article. Here’s a screen grab from the Gaia GPS blog to give you a sense of the improvements from the previous version. Suffice it to say, the new Gaia Topo is much more useful than the old one. Plus, the Gaia cartography gnomes regularly add upgrades and improvements.

A note on map improvements: Map updates appear automatically when you open Gaia Topo in the app or on a desktop computer. However, if you download / save a portion of the Gaia Topo map to your phone and don’t have cell or Wi-Fi coverage, those map updates will not appear automatically; you need to download that area again for the latest map updates to appear. So, if you do decide to download say your entire state or country, you may want to delete it and re-download it about every six months, so you always have the most current map.

Here’s a chart from the Gaia GPS blog giving a comparison of download sizes and speed between the different versions of the map.

A few notes:

It’s highly recommended to download large maps like this on wi-fi instead of using cell data.

To download maps to your phone, you need at least a standard membership to Gaia GPS. (The cost for this is about the same is just one quality printed map, so in my mind it's a pretty screaming deal.) Learn more about their different subscription plans here.

Map scale: If you look at the map scale in the top part of the screen grabs, it says something strange like “Max Zoom 12, 1:192,000”. That scale is incorrect, don't let it throw you off. This map is based on “vector” (line) data as opposed to “raster” (or pixel) data. So, zoom level 12 corresponds to about a 1:8000 scale. If you download at this maximum level of 12, you’ll have an incredible level of map detail, even when you zoom in close. If you have lots of extra memory on your phone, this is recommended. If you're short on phone memory, you can reduce the maximum zoom with the slider bar to make a smaller download file.

I want to mention what appears to be a (hopefully temporary) bug with the app. There appears to be a discrepancy between the original “estimated” download size, and then what the actual download size turns out to be. I reported this bug to Gaia GPS in early July 2020, and their response was, “Thanks for letting us know, we’ll have a look.” For example, look at these two screen grabs. On the left is the estimated size of the download. On the right is the actual size after downloading. You can see there's a difference of about 200 MB. Now, if you have a phone with a huge amount of free memory, a few hundred extra megs and extra minutes of download time is not that big a deal. But if you’re short on phone memory and have limited Wi-Fi, then this download size might become an issue. Just be aware of this.

International coverage

Travelling abroad? Gaia Topo has worldwide coverage in a metric version, along with the same high quality maps. Check out this screen grab; download all of Switzerland for about 100 MB.

Downloading an entire large area ONLY works with the Gaia Topo layer, not other map layers!

Just for fun I tried to download all of Utah using Open Cycle, one of my favorite map layers. Bad idea! This would’ve been 5+ gigabytes to download, taking up way too much room on my phone.

Plus, Gaia GPS has a download limit of 100,000 map tiles for pretty much every map layer (except for satellite, which has a limit of 10,000 map tiles). If you try to exceed this, Gaia is clever enough to give you a red warning text in the upper right corner, letting you know that it’s probably not a good idea.

Downloading odd shaped areas

It might appear that Gaia only lets you download rectangular areas of maps. That’s great if you're after Utah, Colorado etc, but not so helpful if you want to download a large area that's not a convenient rectangle, like Southern California, New Zealand, or some other large odd-shaped land area. But you can! Here's how.

On the phone app or GaiaGPS.com, you need to create and save what Gaia calls an “Area”. This is simply a polygon that can have as many vertices as you want. Then, after you’ve defined your area, you download the map tiles that cover it. Here are a few screengrabs to show the process.

Here's what would happen if you try to download Southern California with the normal download rectangle. Lots of ocean and Nevada that we're not interested in (sorry, Nevada), plus a 453 MB download, ouch! We can do better than that!

On your phone, tap the “Plus” icon from the top row, then tap “Create Area”.

You should see a selection triangle on your screen with five blue dots.

Tap and drag the blue dots to cover your area of interest. Every time you move a dot a new one appears, letting you select large irregular shapes. When you're done selecting Southern California, it should look something like this:

Tap “Save” in the upper right corner. You should get a prompt to “Choose Offline Maps”. Under Resolution, tap “High”. (It actually doesn't seem to matter what resolution you choose with Gaia Topo, the map downloads size stays the same.)

Now if you tap “Save” in the upper right corner the map should start downloading.

Note the download size in the very bottom, 248 MB. That’s a whole lot better than the 453 MB that you would've downloaded if you tried to use a rectangle!

Give the map a few minutes to download. (Remember to do this with a Wi-Fi connection if possible.) To check that it's properly saved to your phone, tap the “Saved” folder icon on the bottom, and select “Maps” from the filter in the top left corner.

Testing your download

Once you’ve downloaded a big area, you can run a test to prove to yourself that the map is indeed saved properly onto your phone and it’s ready to use outside cell phone coverage.

Go to your phone settings, and turn on Airplane mode. This should turn off your Wi-Fi and cell coverage.

Zoom into some part of the country you’ve never been before. The map should look blurry and terrible, because your phone is not able to download the map tiles on the fly like it normally does.

Now, while keeping Wi-Fi and cell coverage off, zoom in to a part of the large map area that you downloaded. The map should look crisp and clear. This proves that it’s on your phone and ready to use when you don’t have cell coverage.

And, if you zoom / pan carefully right to the edge of your download area, you should be able to see a noticeable change in map quality between what was downloaded on your phone and was not. Here's an example of that. The bottom half of the image with the better quality contours is what's actually saved onto your phone.

The new (and much improved) "Gaia Topo" map layer

Gaia GPS made a big update in 2020 to their standard base map, called Gaia Topo. Learn some of the upgrades and see some examples of different zoom levels. It might be the one go-to map layer that you can use for almost everything!

“Gaia Topo” Yosemite example, older version (top) and 2020 version (bottom)

IMAGE: HTTPS://WWW.INSTAGRAM.COM/P/B8HZPDJNB3B/

Gaia GPS is one of the most popular phone based backcountry GPS navigation apps, for good reason. It has lots of features that backcountry users love, but until recently, their default map layer was not necessarily one of them. (And, I’ll mention that I have a Masters in Geosciences with an emphasis in cartography, so I have a pretty good eye for this kind of thing.)

The default “Gaia Topo” layer, when it first came out, was pretty rough around the edges. The contour lines were jagged and visually obtrusive, the zoom layers were not consistent, the map colors were not very attractive, urban areas were lousy, the Points Of Interest (POI) were lacking . . . It got the job done, but it hurt my eyeballs to scan it more than a few minutes. It was clunky enough so I rarely used it, instead cobbling together various combinations of Open Cycle, USGS quad maps, Forest Service maps, and satellite imagery, depending on sport and location. Yes, keeping track of these different map downloads was a substantial headache, especially on my older phone with limited memory.

Well, happily that’s all a thing of the past. In January 2020, Gaia GPS introduced a new and vastly improved Gaia Topo map layer that has loads of great features, enough to probably serve as the only map layer needed for many people. Let's look at some of these features, and then some examples.

International coverage? Oui! Here's Chamonix.

image: gaiagps.com

What’s cool about the new “Gaia Topo” layer?

Progressive zoom levels - Greater map detail doesn’t show until you zoom in fairly close, making the map much cleaner.

“Easy on the eyes” color palette.

Subtle relief shading, enough to give you a slight sense of where the high terrain is but not so heavy that it overwhelms other map features.

Public lands indicated by subtle color shading, A great help if you want to find a free place to pull over and sleep for the night on state or Federally owned (Forest Service or BLM) land.

Much better in urban areas, showing major / minor road networks, parks, and color-coded Points of Interest (POIs) like restaurants, gas stations, medical clinics/hospitals, parks, museums, and more.

More POIs of direct use to backcountry users, such as campgrounds, trailheads, popular rock climbs, hot springs, river campsites for multi-day whitewater trips, ski runs and nordic trails, backcountry ski huts, dog parks and more.

Suggestions for nearby routes - Tap a campground or trailhead, tap the “info” icon, and get a highlighted map and often a photo to the destination. Scroll down a bit further to see other nearby hikes. (This feature has a few extra tricks to leverage for full advantage, read the article at Gaia GPS to learn more about it.)

Worldwide coverage, available with metric elevations in the “Gaia Topo meters” layer (for those who live outside the only 3 non-metric countries: the United States, Liberia and Myanmar).

Based on the Open Source map project Open Street Map, which means that the map is constantly updating as contributors around the world add data, making it is as accurate as possible.

It’s the default free layer on the Gaia GPS website . (Free, one of my favorite words!)

Probably the best thing, MUCH smaller map downloads! Why is this great? Now you can download an entire large Western state, (or say, all of Switzerland) onto your phone at a rather modest file size of around a few hundred Mb and a few minutes download time on Wi-Fi. This means you will pretty much always have the maps you need at the highest zoom level on your phone, with no need to remember to download them before you leave for a specific area that’sa outside of cell coverage. This is a HUGE convenience!

A note on map improvements: The crew at Gaia GPS is constantly updating this map. You’ll see the latest updates appear automatically when you open Gaia Topo in the app (with Wi-Fi or cell coverage) or on a desktop computer. However, if you download / save a portion of the Gaia Topo map to your phone and don’t have cell or Wi-Fi coverage, you need to download that area again for the latest map updates to appear. So, if you do decide to download say your entire state or country, you may want to delete it and re-download it about every six months, so you always have the most current map.

Note: while you can explore this map layer with a free account at GaiaGPS.com, you need a basic paid Gaia membership to be able to download maps to your phone, Go here to learn more.

Here’s a screen grab from Gaia showing some comparisons of download size and speed for different areas.

image: blog.gaiagps.com

Let's look at a few examples, mostly some before/after screen grabs from the Gaia GPS blog. I don't think there's a need for commentary on these, the images pretty much speak for themselves. Which map would you rather use?

image: blog.gaiagps.com

image: blog.gaiagps.com

image: blog.gaiagps.com

A good way to get a feel for it is to go GaiaGPS.com, find an area you're familiar with, click through the progressive zoom layers from far out to close in, and notice how the map detail changes. (You can do this for free, and you don’t need a Gaia GPS account.)

Let's do this for the south Lake Tahoe area. "(Note the scale bar in the lower left corner, starting at 10 mile zoom). Tap the “plus” icon in the upper left corner to zoom in one level at a time, or the mouse scroll wheel if you have one.

Good general overview. Public lands shown, major cities and roads, and the Pacific Crest Trail west of the lake.

Next level: More trails and smaller roads, a cluster of POI icons.

Next level: Still more trails, more POI icons, parks, peaks, roads, campgrounds, and waterways labeled.

Next level: Contour lines and smaller streets appear. POI clusters of smaller features shown.

Next level: Very detailed contour lines, pretty much every path and street shown, most every important feature labeled.

Look at stream flow patterns to see elevation change

From a quick glance at stream patterns on a map, can you get a sense of where the high and the low elevations are? It's a helpful skill you can quickly learn.

Stream flow patterns on a topographic map can show you at a glance the higher elevations and lower elevations.

This map section below (from the US Geological Survey 7.5 minute map series) is in the Oregon coast range. Just by looking at the stream flow patterns (and without looking at the printed elevations (which are pretty darn hard to see anyway) can you tell where is the high ground and the low ground? And, for extra credit, what’s the lowest point on the map?

Here are a few ways to tell general map elevation from stream flow patterns.

A good starting assumption: water flows downhill. =^)

Smaller streams flow together to become larger ones.

When streams come together, they usually form a “V” shape. The two arms of the “V” point upstream, to higher ground. The tip of the “V” points downstream, to lower elevation terrain.

The origin of a stream on a map is called the “headwaters”. The stream always flows downhill from that point.

Contour lines always bend to point uphill when they cross a gully or drainage.

Let's look at a few examples.

When streams come together, they usually form a “V” shape. The two arms of the “V” point upstream, to higher ground. The tip of the “V” points downstream, to lower elevation terrain.

The origin of a stream on a map is called the headwaters. The stream always flows downhill from that point.

Contour lines always bend to point uphill when they cross a gully or drainage. (Look at the index contours, printed in bold every 5th contour line, they’re easier to see. Shown in red line below.)

So, when we put all that together, we see that Jordan Creek in the center is flowing from right to left (or east to west, if you prefer), being fed by various other creeks flowing from higher elevations.

Try this yourself. Go to Caltopo.com, zoom into a familiar area that has some streams, and see how all of these factors come into play.

And finally, because we know Jordan Creek is flowing from right to left (and because water flows downhill) the lowest point on the map is the one indicated below.

And as always, stream flow patterns, gullies, ridges and other landscape features are much easier to see when you use a map that has shaded relief. This is easily done in Caltopo for free. The map below has about 30% relief shading. Here’s a whole article on shaded relief, check it out!

If you are new to using Caltopo, it’s a wonderful mapping tool. I made a tutorial video on how to get started using it, you can watch that here.