Alpine Tips

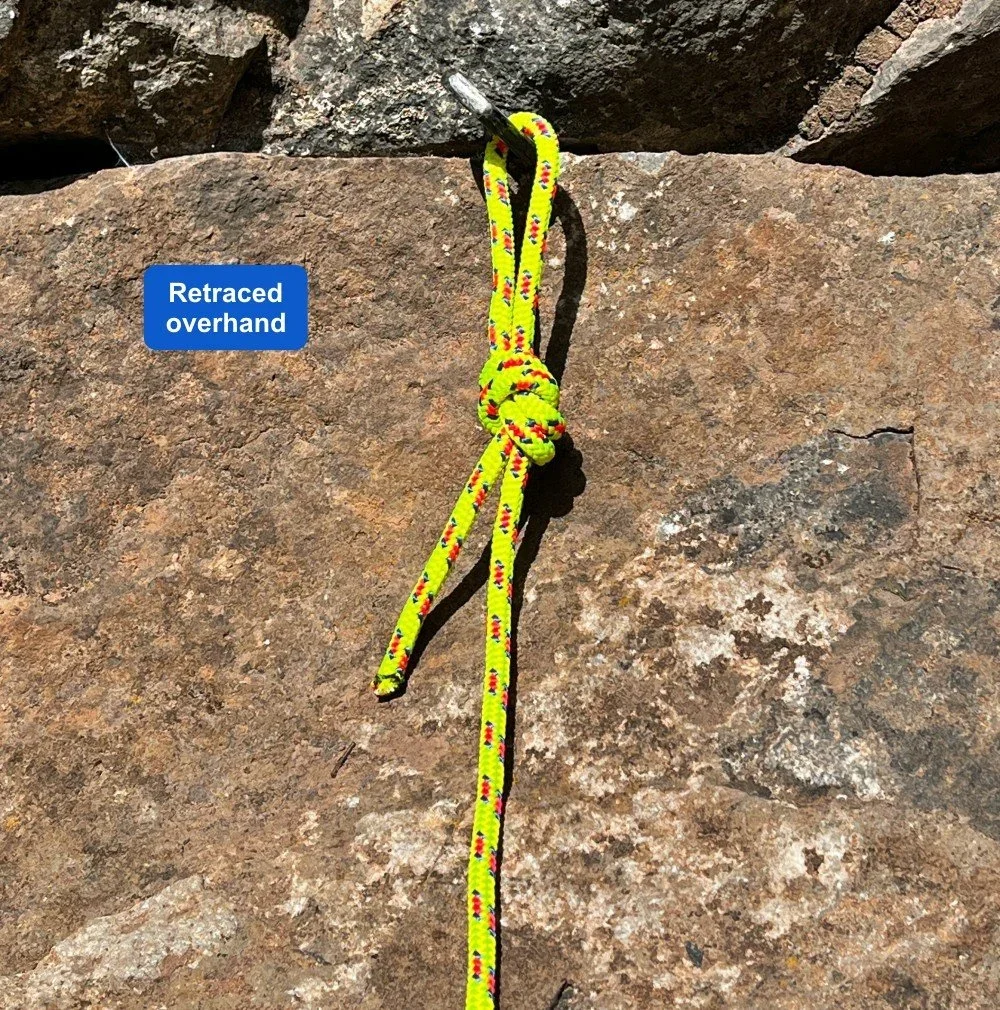

The retraced overhand knot

A close cousin of the retraced figure 8, the retraced overhand knot has a few niche applications, like making retreat anchors. Learn about it here.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

All climbers know the retraced figure 8. Meet the cousin: the retraced overhand.

Here I’m using it to tie a 6mm anchor cord through a fixed piton. You could tie a retraced figure 8 here as well and it would be fine.

However, the retraced overhand is a little simpler to tie, and it uses less material. So in this particular application, it may be a better choice.

It’s also is gonna be a little harder to untie after loading, so that's the trade off. In this case, you're leaving it behind for a rap anchor, so untying it is not an issue.

Being able to directly tie to fixed gear like this is one more benefit of carrying an open cordelette, as I detail in this article.

This knot is closely related, but a bit different from the “brotherhood” or “competition” knot. See the photo at the bottom of the page.

How to tie the retraced overhand knot

Start by tying a loose overhand knot about 1 foot / 30 cm away from the end of your cord.

Pass the end of the cord through the gear, here a fixed piton. (Check the piton to be sure it doesn't have any sharp edges.)

Start retracing the knot, very similar to how you tie a retraced figure 8.

Continue tracing the overhand knot with the end of the cord.

This is the shape of the knot before it gets “dressed and stressed”.

Dress the knot well - snug down all four strands, and be sure you have a tail of at least 3 inches / 8 cm or so.

(And yes, the loop in the knot could be even smaller if you wanted to use even less cord.)

Done!

What's a practical application for this, and how would you rig it?

What's the difference between this and the so-called “competition” or “brotherhood” knot, another flavor of the retraced overhand?

Join my Premium Membership to read the rest of the article.

Thanks for your support!

Need a stronger anchor? Try a basket hitch

Want to boost the strength of your rigging? Simply doubling the strands into a basket hitch can dramatically increase the strength, which could be helpful in some situations. See the test results here.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

A basket hitch (and no, I don't know why it's called that) is pretty simple. It’s a loop of loop of webbing, cord, or rope, doubled into a “U” shape.

Takeaway: a basket hitch more or less doubles the breaking strength of whatever material you’re using, because the load is shared over four strands instead of two.

For most climbing situations, this doesn't really apply much, because the maximum possible forces in any recreational climbing situation are never going to be more than about 9 kN. If you're using a sewn sling that has a Minimum Breaking Strength (MBS) of 22 kN, no worries.

And, even clipped in the regular end to end method shown below, the 28 kN where it broke is probably stronger than your carabiner!

But in a few cases that I can think of, knowing a trick to increase the strength of your rigging might be helpful:

You need to use some skinny 5 mm cord for some kind of anchor building or application that it's not really designed for, and you want to squeeze some extra strength from your material.

If you want to do something involving possible LARGE forces, such as pulling your car out of the ditch, dropping a big tree limb, or detaching a wrapped whitewater raft off a rock.

My friend Ryan Jenks, the mad scientist gear-breaking genius behind the great YouTube channel HowNOT2, did some break testing on this.

Here are Youtube screenshots of the results of three different break tests. He’s using a standard sewn 8 mm Dyneema sling, rated with an MBS of 22 kN.

Photo 1: The sling gets a “normal” end-to-end pull. It broke well above the 22kN MBS, which is a good thing.

Photo 2: The same 22 kN sling, this time doubled with a basket hitch. With this rigging, it more than doubled the MBS.

Want to see the ACTUAL break test results for the basket hitch?

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

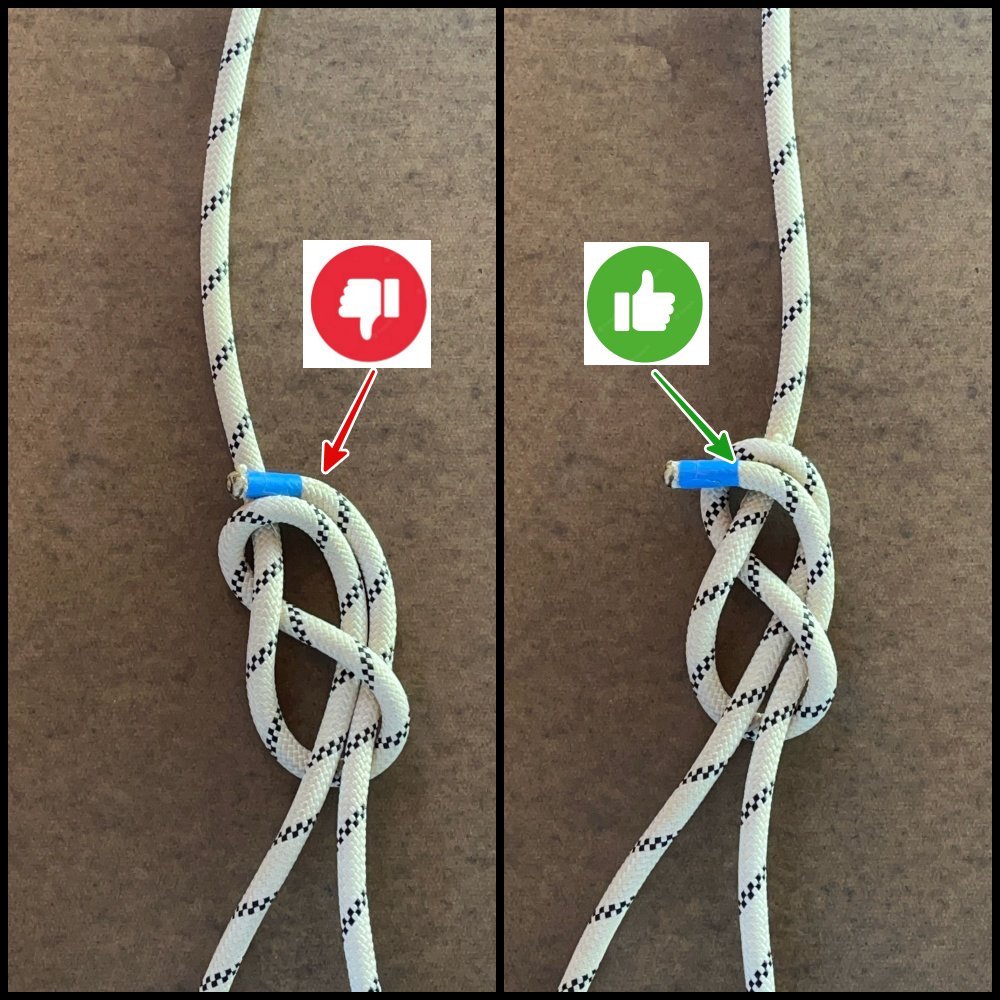

Klemheist ver 2.0: stitching IN the knot

A Klemheist is a useful friction hitch / rope grabber, but DANG, have you ever tried to use it to actually go up to fixed rope? Tied in the normal way, that sucker bites down hard and is really difficult to slide! Here’s a clever variation that gives adequate grab on the rope, and is much easier to slide when you need to move up.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

Credit for this method goes to Silvan Metz, @silvanmetzfotografie

Left photo, normal way to tie a Klemheist. Right photo, the modified method which is much easier to slide.

The Klemheist is one of three friction hitches every climber ought to know. (The other two are the prusik and the autoblock, aka French prusik, or Machard.)

Friction hitches are used typically used as a rope grab in a mechanical advantage haul system, and as a tool for emergency rope ascending.

The Klemheist is handy because you can tie it with either cord or a sewn sling, and you can easily adjust the amount of friction by increasing or decreasing the wraps around the rope.

But DANG, have you ever actually tried to climb a rope with a Klemheist, especially one tied with a skinny Dyneema sling? You probably discovered that it bites down very hard on the rope, and is very difficult to slide up after you've loaded it with your body weight.

Here's a clever variation on the Klemheist hitch, where the stitching on a sewn sling is intentionally tied INTO the hitch, as in the photo above on the right.

WTF?! I learned in Knots 101 you should never do this, why would you?

Answer: for ascending a rope.

By including the stitching in the hitch, it allows enough friction for good grabbing on the rope, but also allows the knot to MUCH more easily slide on the rope when you need to move it.

Notes . . .

Works great with a sewn sling, even Dyneema (Don’t use Dyneema for a rappel backup.)

Grabs pretty well in both directions, but still holds best in one.

Easily adjustable with the number of wraps; more wraps for a skinny rope, fewer for thicker ropes or twin strands.

Some people think this is a Hedden hitch, or maybe an FB hitch. To be honest I don't really care about the name. It's more important to know how to tie it and the best applications, so let's not get distracted by lineage and whether I use the exact right term to describe it. Lots of “knot-knerds” like to argue about stuff like this. I’m not one of them.

Want to learn how to tie it, with a video from Silvan?

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

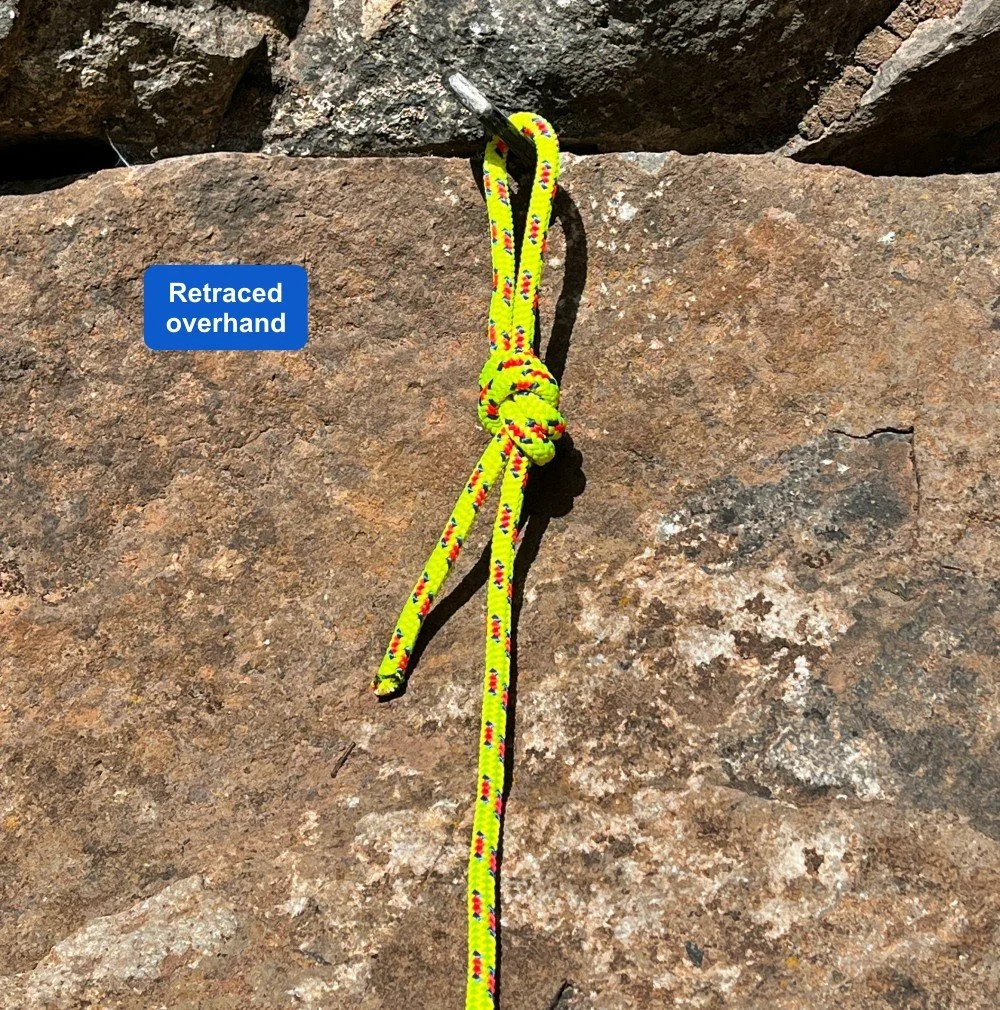

Do you need a triple fisherman's for tech cord?

A long-standing “rule”: always use a triple fisherman's knot to connect ends of “tech” cord, that has a Kevlar / Aramid core. Is this really true? What happens if you tie a double fisherman's instead? Here's the answer, courtesy of the gear breaking lab at HowNOT2.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

General climbing wisdom:

Use a double fisherman's knot to securely connect cord ends to make a permanent loop (like for a cordelette) in standard cord.

Use a triple fisherman’s knot to securely do this in so-called “tech” cord, that might have a Dyneema or Technora/Aramid/Kevlar core.

(Sidenote: yes, this several-different-names-for-the-same-thing is confusing! “Technora” and “Kevlar” are trademarked names. “Aramid” is a more general name, sort of like “Kleenex” and “facial tissue”,

I sure remember learning this when I first started climbing. Way back then, about the only tech cord available was this extremely stiff Kevlar cord that we used for stringing hexes (remember those?) With that ancient cord, the triple was the way to go.

Turned out that that extra stiff material didn’t have very good fatigue resistance, so it fell out of favor. Modern Aramid cord like Technora is more supple, and is more resistant to fatigue, i.e. repeated bending in the same place, like what happens inside a permanent knot.

The classic triple fisherman's knot endures in the modern era. The question is, do you still need a triple fisherman’s, or will a double work?

Ryan Jenks, the gear breaking mad scientist genius behind HotNot2, did some testing on this, using Sterling Powercord. This is very nice cord: 6 mm, rated to 19.5 kN, nylon sheath with a Technora core.

Here are the break test results (yes, small sample size of 1)

Powercord double fisherman's: 18.7 kN.

Powercord triple fisherman’s: 21.9 kN

So . . . the triple was a bit stronger, but the double was quite close.

Given about the largest possible force in recreational climbing is around 8-ish kN, and your spine is going to start breaking around 12, the double fisherman’s appears to be just fine.

The main advantage to using the double? You use less cord to tie it, which is less expensive and a little bit lighter. Is there any downside to using a triple is it makes you feel warm and fuzzy? Not really.

Want to see the break test video and all the test results?

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

Big load on a bight knot? Try a butterfly

Is your bight knot going to take a BIG load? Consider using a butterfly instead of a figure 8 or an overhand. The butterfly is usually a lot easier to untie after it takes a heavy load.

There are three bight knots commonly used in climbing:

overhand

figure 8

butterfly

(Yep, I'm calling it a butterfly, and not an “alpine” butterfly. I don't see any need for the word “alpine”, and I like simplicity.)

If you're putting any significant load onto this knot, consider using the butterfly.

It's usually much easier to untie after being loaded than the other two, with the overhand usually being the most difficult. (Most big wall climbers, who regularly deal with heavily loaded knots, have known this trick for a long time.) In the photo below, we have a figure 8 on the pig, because that’s pretty much a permanent knot in your haul rope that stays there all the time.

Of course, “hard” or “easy” is subjective! Factors such as your finger strength, level of patience, whether your rope is old and crusty or new and slick, wet or dry, can all have an effect.

What about a bowline?

A bowline is also easy to untie after being loaded. However, it has a tendency to loosen if it's subject to repeated loading and unloading, and it also needs some sort of backup. Also, it's tricky to tie as a bight knot in the middle of the rope, as we're doing here.

So, in most recreational climbing applications, one of the three bight knots listed above is usually preferred.

Munter hitch to clove hitch conversion

Are you belaying your second up on a Munter hitch? (Yes, old school, I know). Here is a very #CraftyRopeTrick to convert that Munter into a secure clove hitch once they arrive at the anchor. Even if you think you would never use this, it's a fun little bit of rope wizardry to practice. Check out the short video to learn how.

Yes, belaying your second from a Munter hitch is a bit of an old-school technique, but it can be helpful in certain situations.

Once your second arrives at the anchor (and is at a reasonably secure stance) whip out this clever bit of rope sorcery to convert that Munter into a clove hitch.

Doing this immediately secures them to the anchor, without any additional knots, tethers, etc.

It looks like a rope magic trick. After you flip the first loop back through the carabiner, you seem to have made a total tangle. But then unclip the correct loop, and that ungodly mess magically transforms into a clove hitch. #CraftyRopeTrick, for sure!

Yes, this technique does involve unlocking the carabiner gate and flipping the rope through twice momentarily. Provided the second is reasonably balanced and secure, this should not be a problem. Or, maybe this technique is just not for you and you can skip it, that's cool too. =^)

Note: the last movement of doing this, when you unclip one strand, requires you to be 135% sure you’re doing this correctly; otherwise there's a risk of you completely unclipping your partner from the anchor. Practice this a bunch and be sure you have it down correctly before you ever do it in the real world! If you're not sure you're doing it right, then don't do it!

There are at least two different variations on how to do this, I’m showing one. Even if you think you might not use this, it’s worth practicing just for the magic trick / entertainment value. :-) Like most things related to knot tying, it’s just about impossible to explain in words, but very easy to learn from a video.

Check out this nice video from Petzl Germany on how it's done.

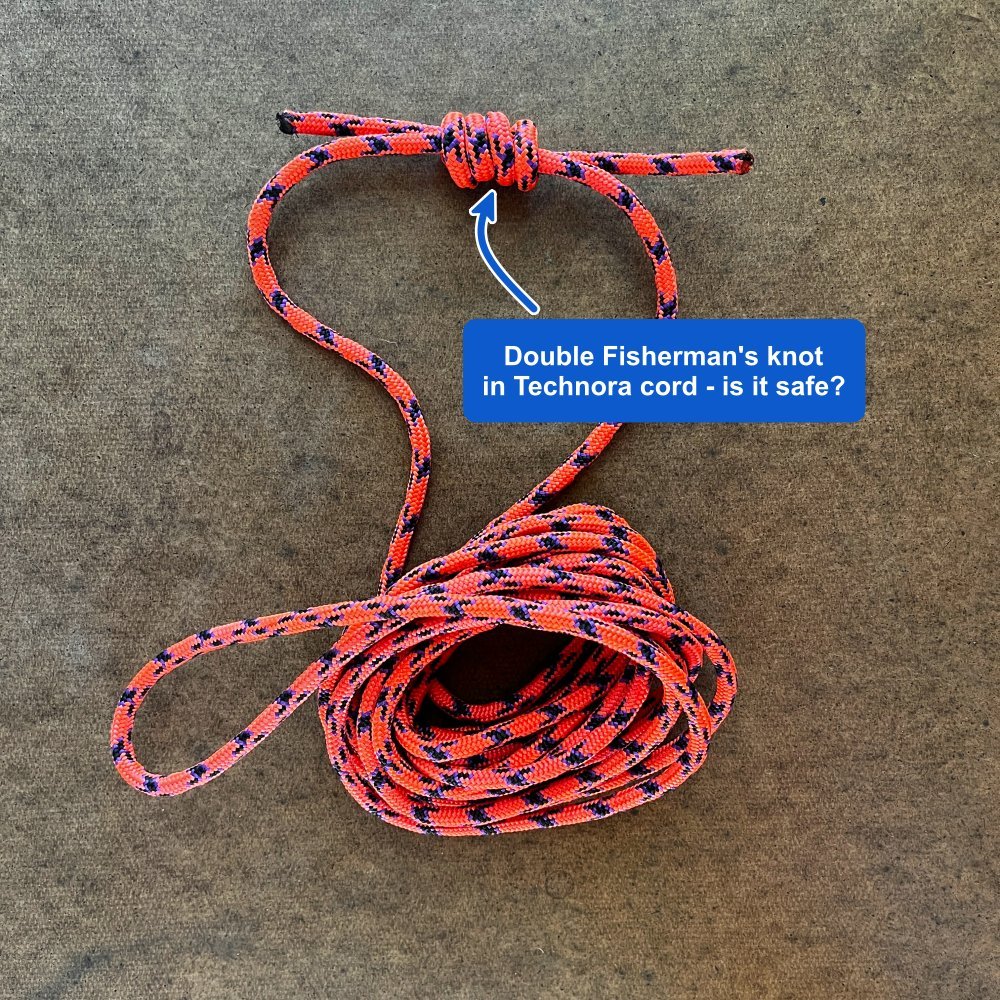

How to tie the perfect retraced figure 8

The retraced figure 8 is probably the most important knot you'll ever tie, so let’s learn the nuances of tying it correctly, every time. There's more to it than what’s usually taught in books and by many instructors. Learn the tricks to make a perfect figure 8, plus how to do it so it's much easier to untie.

The retraced figure 8 tie in knot is probably the most important knot you’ll ever tie, so it's well worth it to pay attention to the small details so it's perfect every time. No twists, crosses, or other weirdness! (A figure 8 doesn’t need to be tied absolutely perfectly to function. If you have a twist or cross in the strands, it's still going to be fine. However, it is the fundamental knot in climbing, so let's take the time to do it right!)

Lots of instruction on the retraced figure 8 (be at books, video, or in person) fall short in explaining it properly. Simply saying, “Tie an 8 about a meter from the end of the rope, pass the free and through your harness, and then retrace the 8” doesn't tell the whole story. There are quite a few different ways you can do this, and many of them lead to an end product that’s Less Than Ideal.

I’m going to show you the way that works best for me, that I teach, and that people seem to find the easiest to learn. If you have a different way that works for you, and the result is a perfect knot, then keep doing what you're doing!

Let's learn some of the nuances of a perfect retraced figure 8 knot.

First off, avoid talking when you or your partner are tying into the rope. Like packing a parachute, your tie-in knot is worthy of your complete attention, so stop the chitchat for a few seconds when tying in.

It may be tempting to begin the knot like the left photo below, because that's where the large obvious “hole” is. However, this often leads to crossed strands in the final knot. (Yes, there is a way to tie a retraced figure 8 correctly by doing this, but for most people that leads to twists and confusion.)

Instead, begin your knot as shown on the right.

Some instructors call this “start hard, finish easy.” This advice is a little cryptic, but it means start the knot through the hard-to-see, non-obvious “hole”, and finish the knot, with the remaining two passes, through the the easy-to-see, obvious “holes”.

(I put blue tape on the end of the rope to more easily see it.)

This next photo shows a problem that trips up many experienced climbers. (And yes, I’ll admit that I did this step wrong for quite a long time . . . )

In the left photo, if you pass the end OVER the top of the knot, you end up with the strands crossed when you're done. (At least, I always did!) While you can correct it later, why not do it right the first time?

Pass the end of the rope BELOW the top of the knot, as shown in the photo on the right. This gives you a perfect symmetrical knot when you're done, no twists or crosses.

If you make either of the two goofs above, your completed knot will probably look something like the one on the left below. See how the strands are crossed? That's not a catastrophic mistake, but it's not 100% correct either.

Below on the right is a proper retraced figure 8. All strands are nice and tidy, parallel, with no crossing or twisting.

There’s also a proper length tail on both knots, not too long not too short. Ideally the tail is about 6 inches / 15 cm. If your tail is shorter than this, start over. If your tail is longer than this, you can tie an overhand knot to take up the extra. But it’s unnecessary and doesn’t add any extra security to the knot, in spite of what the rules might be at your local rock gym.

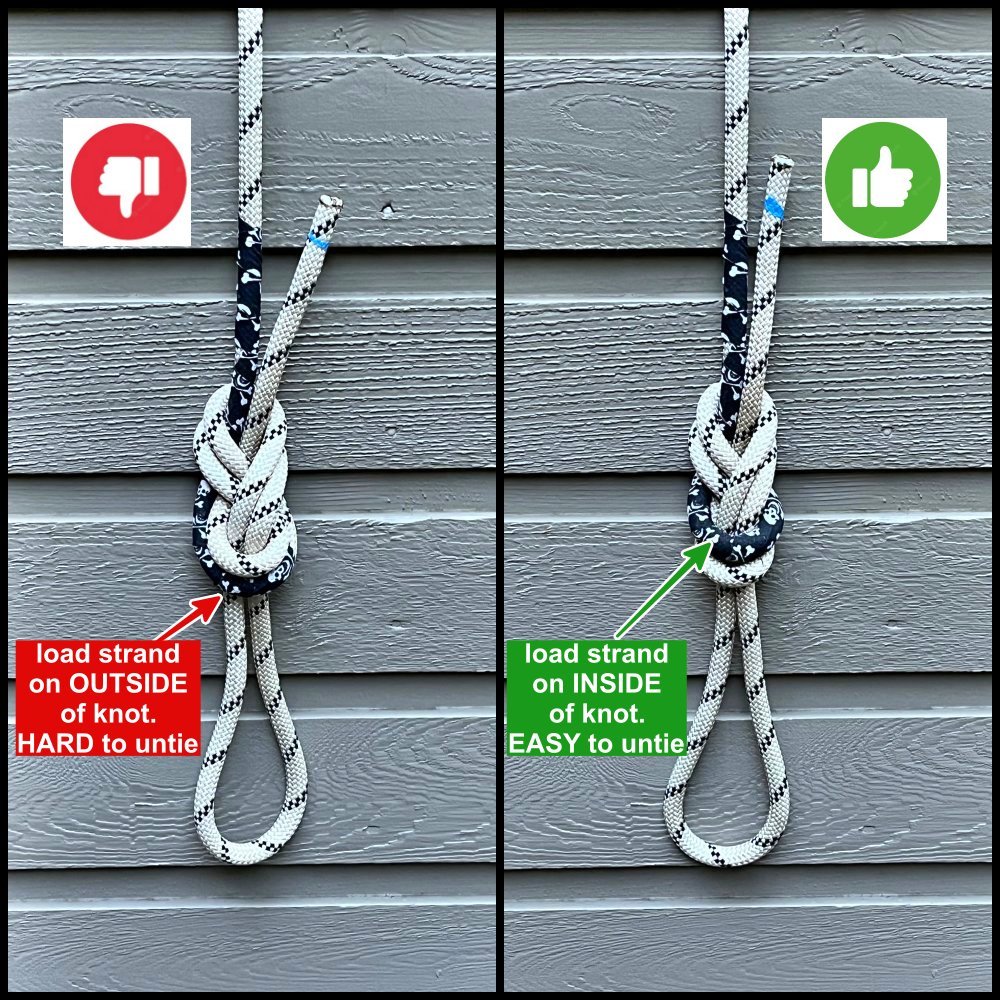

There's another subtlety for tying a correct figure 8, and that is keeping an eye on where the load strand goes. (If you tie it like I showed above, the load strand will always be in the correct place.)

Let’s add some tape so we can more easily see what's going on. (Note the skull and crossbones hockey tape, my favorite for marking soft goods like slings! =^)

The load strand on the left comes out on the OUTSIDE of the knot.

The load strand on the right goes through the MIDDLE of the knot.

Most people find the knot on the left to be significantly harder to untie. It can depend a bit on how much load you're putting on it, the type / diameter of rope you are using, etc.

Why?

Load strand on the outside of the knot: When loaded, this cinches down on the entire knot, even to the point of partially deforming it. No loose strands, welded, hard to untie.

Load strand on the inside of the knot: the very top strand goes to the rope tail, and takes minimal load. This gives you a slightly looser strand to start with when you need to untie it.

Both versions are equally strong and secure, the difference is only in the ease of untying.

When I posted this on Instagram, a substantial number of people commented that I was completely wrong, and having the load strand on the outside of the knot makes it easier to untie. Well, maybe that works for you, but it's not my experience, nor what various other rope experts have to say on it. The relative ease or difficulty of untying a knot is a fairly subjective judgment. Try both ways yourself and see what you think.

Check out the nice video below from “Hard is Easy”for a very thorough discussion of every step tying a retraced figure 8. If you’re a new climber you may benefit from watching the whole thing. If you're more experienced, start at 7:08 to see some of the methods discussed above.

The Figure 9 knot

The “Figure 9” is a variation of the standard figure 8 on a bight. The figure 9 simply takes an extra wrap of cord. This can help raise the master point a bit higher. (Many people think that the figure 9 is easier than the figure 8 to untie after loading, but it turns out this isn’t always true.)

The figure 9 is pretty much the same as figure 8 on a bight. The one difference is you make an extra twist before you tie it.

Why might you want to use the figure 9?

Because the figure 9 uses extra cord, this raises your master point a bit higher, which may be more ergonomic. Check the photos below, you can see how the figure 9 gives the highest master point.

Admittedly this is fairly rare, so most of the time the figure 8 is going to be the better choice.

A possible downside: the figure 9 may not be as recognizable as the figure 8, so you might have to explain to your partner what the hell you're doing. =^)

The sling I'm using is the Edelrid Aramid cord, my favorite for anchor building. Strong, very durable sheath, and easy to untie after being loaded, no matter what knot you use. Here's a longer article about these slings.

Lots of people think that figure 9 is easier to untie then the figure 8, but depending on your loads and the rope/cord you're using, that may not be true. Check out this video below from The Rope Access Channel on YouTube. He puts about a 480 kg load on both knots and tests which is easier to untie. Hint, it's the eight.

In the video below, the test goes from about 2:45 to 6:00.

Tame skinny ropes with a daisy chain

Long lengths of skinny rope, such as a 6 mm rappel pull cord, can easily turn into a hopeless tangle if you're not careful. Solution: the daisy chain. This “crochets” a rope into a series of short chain links, reducing the length by about a factor of six. A daisy chained rope is pretty much impossible to tangle when stored, and easy to deploy when you need it.

Daisy chain, lineman’s coil, chain sinnet. A few different terms that mean the same thing: to do a little crocheting on your climbing rope to help it stay tangle-free in your pack.

Daisy chaining your rope can be especially helpful when using a long length of tangle-prone skinny rope, such as like the Petzl PURline or RADline, or a rappel pull cord. The photo above shows a 30 meter RADline.

(It also works great to bundle up long electrical extension cords, which is where I first learned this trick doing construction way back when.)

If the rope is inside your pack, a daisy chain lets it smoosh it around and better fit the contours of your backpack and other gear, as opposed to a butterfly coil. If you’re carrying your rope draped over the top of the pack, then a butterfly coil is probably a better choice.

And, even if you don't have a skinny rope to deal with, it's still a fun rope trick to play around with and practice, so get out your cordelette and give it a try!

How to make a daisy chain

I like to start at the middle of the rope. (Your rope DOES have a middle mark, right?) Make a girth hitch, reach one hand through the loop you made, and grab two strands of the rope. Pull these two strands through the girth hitch loop, forming a second loop. Reach through that loop, grab two strands, and repeat. (Congrats, you just learned to crochet.)

When you’re done, the rope will be in a series of what looks like chain links. In link, you’ll see six strands of rope. So, the daisy chain effectively shortens your rope by a factor of six. That means your 60 meter climbing rope is now a much more manageable 10 meters long. You can take a daisy chained rope and stuff/smash/smoosh it around all you want, and it’s never going to get tangled up.

To deploy the rope, find the ends of the rope and pull on them. The entire daisy chain should magically unravel itself, and you should be left with a nicely flaked rope with both ends on top.

(Another good approach for managing a long length of skinny rope is a rope bag. It doesn’t need to be fancy, a reusable plastic grocery bag with sturdy handles works fine, packs down very small, and weighs just 2+ ounces / 60ish grams.)

Like most everything to do with knots, it’s a better show then a tell. Check out the video below to see how it’s done.

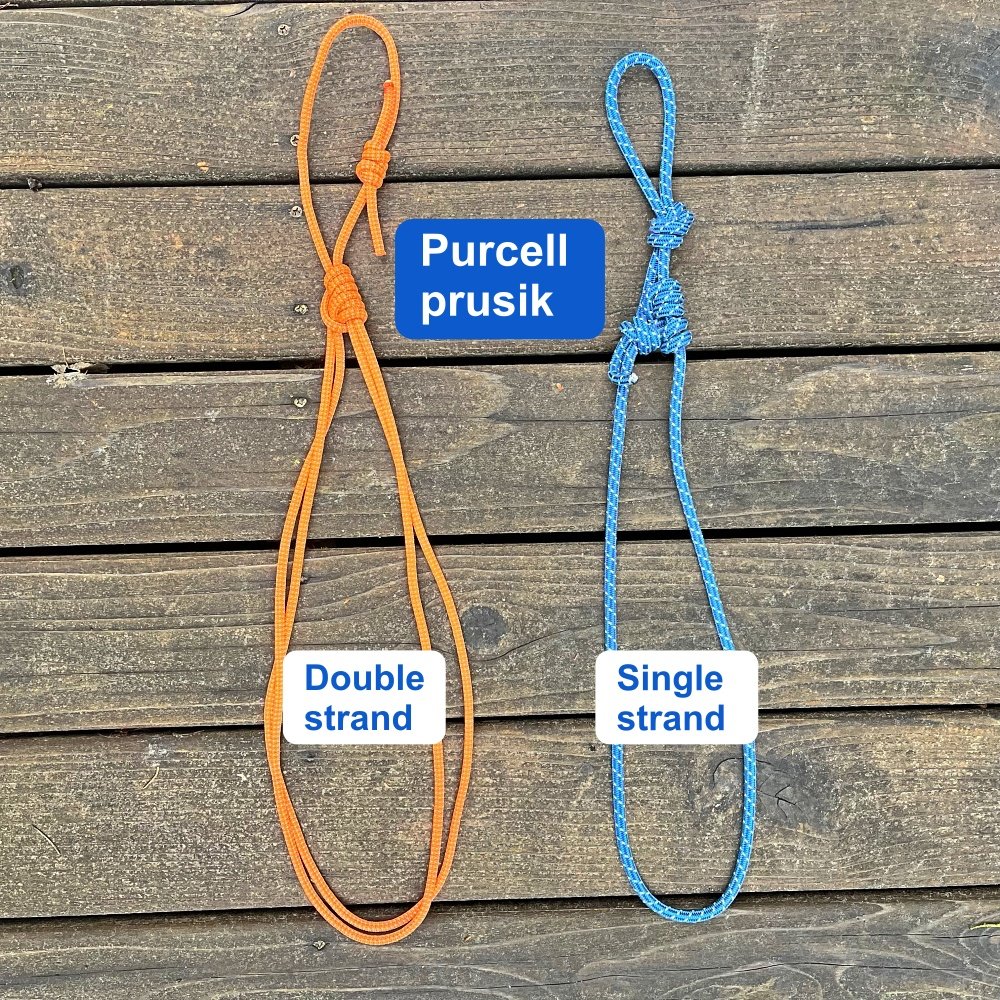

Single strand Purcell Prusik

The Purcell prusik is an interesting bit of ropecraft good for certain applications, but it's a bit clunky and tangle-prone. Here's a more streamlined variation: tying it with a single strand.

This Crafty Rope Trick comes from my canyoneering expert buddy Kevin Clark. Check out Kevin's book, “Canyoning in the Pacific Northwest”. Kevin learned it from Ben Lewis, a canyoning expert who made the video at the bottom. Thanks, Kevin and Ben!

The Purcell prusik is named after the Purcell Mountains of British Columbia Canada, and was invented in the 1990s by Canadian IFMGA Guide and rigging expert Kirk Mauthner.

The Purcell prusik is an interesting, sometimes useful, and sort of klunky bit of ropecraft.

Tied in the usual way, it consists of a prusik hitch sort of tied back onto itself to make an double strand adjustable loop. (The method shown here is a bit different than how it was first introduced.)

This has a few applications in self rescue, rope ascending, rigging mechanical advantage systems, adjusting rescue litters, and impressing your knot-nerd pals. One useful feature is that it can be extended under load, which makes it handy for knot passing and other rescue-type stuff. Plus, it’s inexpensive.

But it has a few downsides:

it’s bulky

the twin loops tangle easily

you need two hands to shorten it

it only adjusts from full length to half length (unless you know a certain #CraftyRopeTrick, see below)

Some climbers use the Purcell prusik as a personal tether or ice ax leash or something similar. But the hassles listed here mean it’s not part of everyday gear for most people. (If you want an adjustable tether, a more modern approach is something like the Petzl Connect Adjust, or a DIY version, the Kong Slyde.)

Here’s an interesting variation: the single strand Purcell prusik.

Because it’s tied on a single strand, it’s lighter, lower bulk and less tangle prone than the regular double strand version. (It still has the downsides of only adjusting from full length to half length, and needing two hands to shorten it,)

You could use a few different materials to tie it. 6 mm accessory cord works for things like an ice ax tether, or some connection that’s not going to be taking much force. Remember, 6 mm cord is rated to about 7.5 kN, and when knotted, it’s going to be about half that, more like 4 kN, so it’s probably not something you want as a load bearing anchor. (But 7 mm cord is rated to a stout 13 kN, that’s an option too.)

Here’s a single strand Purcell prusik made with about 8 feet of 7mm cord. Much more stout at 13 kN, fine for anchoring.

If you want light and strong, you can tie it with Sterling PowerCord, a svelte cord at just 5.9 mm with a Technora core that’s is rated to a burly 18 kN, plenty strong enough for a serious anchor even with a knot in one end.

Side note: PowerCord is a great choice for a cordelette.

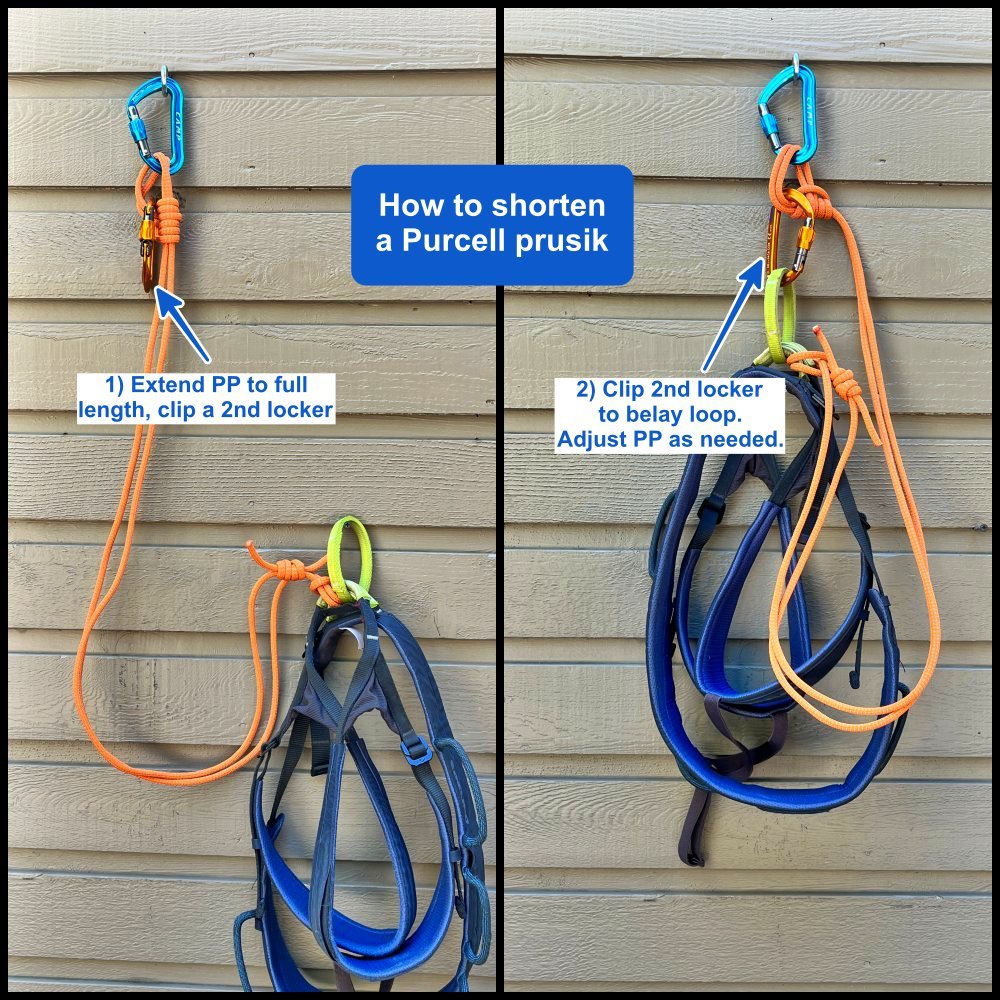

Lots of people think that one of the main problems with the Purcell prusik is that you can never get it any shorter than half the length. So, how do you stay clipped in very close to something?

I thought this too for a long time, until I learned this #CraftyRopeTrick from my pal Ryan at HowNot2. He shows it the video at the bottom of this page. (The photo below is with a standard double strand, but it works the same way with a single strand.)

Extend your PP all the way, until there's just a tiny loop of rope at the end. Into this loop, clip a second locking carabiner.

Now, clip this second locker to your belay loop. Now you can clip just two carabiner lengths to anything. Plus, you can increase the size of this loop by feeding cord through, to adjust your distance as needed.

Kind of for fun, I also made a single strand Purcell prusik into a double tether, tied with about 14 feet of 6mm cord. Applications for this . . . ? Aid climbing tethers? Foot loops for ascending a rope? Maybe ice tool tethers? Doing rigging or rope work or routesetting and you have these attached to your tools, drill, bucket, whatever? I was experimenting and haven't used it in the real world, but give it a try and let me know how it works for you.

Now, I get it that lots of people don’t like to carry any kind of designated tether, and that’s fine. I’m putting this tip out there for people who might find it helpful. At the very least, it’s an interesting bit of knotcraft to play around with, so try it yourself and see how it works, even if you don’t think you’ll find a use for it.

Check out the video by Ben Lewis to learn how to tie it. (You’ll probably need to watch it a couple of times, hint hint.)

Finally, here's a nice video from our friends at HowNot2 that discuss how to tie the standard version, and some strength tests on it.