Alpine Tips

Top tips: longer phone battery life in the backcountry

Here are detailed tips to keep your phone running longer in the backcountry: changing some phone settings, navigation tricks, and cold-weather protection. Yes, your phone can last for many days on one charge!

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

Except for a few hard-core Luddites, most of us carry phones in the backcountry and are glad we have them. Camera, music, podcasts, journal writing, Kindle book reading, compass, maps, GPS navigation and even flashlight . . . You may only use a couple of these, but even so, prolonging your phone battery charge can be very important.

It's less important on a day hike then a multi day outing, but even then it's good to develop good practices.

Some of these may be iPhone specific, because that's what I have. (You Android folks hopefully have something similar.)

If you have a short attention span, here's the takeaway: 1) Bring an auxiliary battery and charging cable, and 2) keep your phone in Airplane mode.

Here are some battery saving tips, divided into three main sections:

Settings

Navigation

Cold weather

On an iPhone, you can set the few helpful controls in your control center to quickly adjust power savings. I think airplane mode and screen brightness are default. You can also add the low power mode.

Phone settings

If you use almost all the battery saving settings in the section, the baseline battery use (phone is on and asleep, but not being used) is around 3% per day. If you have your phone in normal city settings, with none of the battery savings methods deployed, baseline use can be up to 30%. Yes, that's a huge difference!

Start your trip with a fully charged phone and extra battery. Yes, sounds obvious, but it's easy to overlook this, especially on a short drive to the trailhead.

Bring an auxiliary battery and charging cable(s). There are many options. Go with a name brand battery like Anker. Something around 5,000 mAh (milliamps) can charge your phone at least once. Add a short charging cable and you're looking at around $20 for both. For a longer trip up to a week, consider a 10,000 mAh battery. Charging cables can be delicate and get broken, consider bringing a spare. Get into the habit of bringing these on every trip, even a day hike.

Turn on Airplane Mode. This is probably the #1 habit to develop at the trailhead, and a good one to remind your team members about. Airplane mode stops your phone from trying to connect to the cell tower network. Especially when you’re out of cell phone coverage, these constant attempts to reconnect can really drain the battery. To check for messages or make a call, turn Airplane mode off for a minute or two if you have coverage, then turn it back on again when you’re done.

Turn on Low Power Mode. This reduces background activity, like downloads and mail fetching, and sets Auto Lock to 30 seconds. On iPhone: Settings > Battery > Low Power Mode

Turn down your Screen Brightness. The screen is probably the single biggest battery drain. If you're going to use your phone a lot, consider doing it in the evening when you can use lower brightness setting. If you need to use your phone during the day, try to find some shade. On iPhone: Settings > Display and Brightness > adjust the slider bar.

Tip for iPhone users: you can set up your control screen to adjust these three settings, see photo at top of the page.

Important: The GPS chip in your phone does not need cell coverage or Wi-Fi, and works fine in Airplane mode.

Turn off Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, AirDrop, and Personal Hotspot. On iPhone: Settings. Airplane mode might turn all of these off at once, but they can individually be turned on even if airplane mode is activated. If you want to use Bluetooth to listen to music on speakers/earbuds, or use a SEND (Satellite Emergency Notification Device) remember to turn Bluetooth off when you're done.

Deactivate Background App Refresh. On iPhone: Settings > General > Background App Refresh. Apps will no longer run in the background.

Set the Auto-Lock to the minimum. Auto-Lock puts your phone to sleep when you're not using it. Sure it's good habit to press the side button and put it to sleep manually, but if you forget to do this and put it in your pocket, a short screen lock time puts it to sleep quickly. On iPhone: Settings > Display and Brightness > Auto-Lock > set to 30 seconds.

Close all open apps. While most apps just sit there and don't do anything, some continue to refresh in the background or even use GPS location data (like Google maps) and suck your battery. Shut down everything you don’t need in the backcountry, which should be pretty much everything.

Set your navigation app to only get your GPS location when you ask for it. Navigation apps need to be on all the time if you’re track recording, but if you only want an occasional position fix, it doesn’t need a constant GPS signal. On iPhone: Settings > Privacy > Location Services > Gaia GPS > Ask Next Time. Now, when you tap the “show current location” icon in your GPS app, you should get a pop-up box requesting access. Tap “Allow Once” to show your location just for one time. Every additional time you open the app you should get this access request.

Turn off Location Services for your camera. Even if you shut down all unnecessary apps, you're still probably going to take some pictures. If you have Location Services on for your camera, every time you shoot a photo that's going to take a little extra power to “geotag” your photo with latitude longitude coordinates. On iPhone: Settings > Privacy > Location Services > Camera > Never or Ask Next Time.

Turn off Data Sharing. As a default, Apple collects a LOT of data on how to use your phone! Your phone shares this regularly, and the files can be as large as 10 MB. Sending these data packages can put a hit on your battery. If you're already in airplane mode this should not be an issue, but why not turn it off? And protect a bit of your privacy at the same time? On iPhone: Settings > Privacy & Security > Analytics & Improvements > Toggle everything off. (If you're curious what Apple is seeing on your phone, while you're there tap Analytics Data > then tap any one of the analytics files. It probably won't make any sense to you, but it's an impressive amount of snooping.

Turn on Auto-Brightness. This automatically adjust the screen brightness according to the light conditions, and can save a bit of battery. On iPhone: Settings > Accessibility > Display & Text Size turn auto-brightness on.

Use Dark Mode. A study at Purdue University showed that for higher levels of screen brightness, which you will probably have if you're outside during the day, dark mode can offer a significant improvement in battery life. On iPhone: Settings > Display and Brightness > tap “Dark”. (Or, ask Siri to “turn on / turn off dark mode”.)

Turn on grayscale mode. On newer phones, showing only grayscale instead of color can increase battery life. This setting is pretty buried. On iPhone: Settings > Accessibility > Display & Text Size (under the “Vision” header) > Color Filters, toggle Color Filters. (Or, much easier, ask Siri to “turn on / turn off grayscale”.)

GaiaGPS settings - GaiaGPS is a popular backcountry GPS phone app. If you tap through to Settings > Power Saving, there are a few adjustments there that can help preserve battery. 1. Keep screen on - toggle off for maximum battery life. 2. Disable altitude lookup - toggle on for maximum battery life.

3. Sync photos on cellular - toggle off for maximum battery life. 4. Better location accuracy when plugged in - toggle off maximum battery life. Note: #2 and #3 are irrelevant if the phone is in airplane mode, since the app won't be able to do those functions without a data connection. #4 will only use more power when plugged in, as the setting says. But possibly someone could have their phone plugged in to a portable charger, so better to leave it off.Power down your phone, if you're really sure you don't need it. If you're confident in the route, have a paper map and decent map reading skills, and don't plan on taking photos with your phone, consider powering it down completely. Note: powering your phone completely off and then on again more than once or twice every 10 hours or so actually uses more battery than keeping the phone on all the time and waking it up from sleep mode. So, for most people, it's probably better practice to keep your phone on and sleep.

Consider powering down your phone at night. Test this at home to see if it makes a difference, see previous Tip. With some phones it does, others not so much. If it's cold, cuddle your phone in your sleeping bag.

Power down your phone, but have your partner(s) keep theirs on. No reason why both phones need to be on if they're not getting much use.

Turn Battery Percentage on. On an iPhone, you can show the percent battery you have left rather than just an icon. Knowing this number is helpful. On an iPhone: Settings > Battery > Toggle Battery Percentage on.

When charging your battery, only charge it when it's below 10% and try to avoid charging it past 70%. It takes more energy to push a battery past 70%, so stopping there helps preserve your auxiliary battery.

Check your battery health. On an iPhone: Settings > Battery > Battery Health. This compares as a percentage your battery with a new one. A lower percentage means a full charge doesn’t last as long. If capacity is less than 80%, consider replacing your battery; Apple consider this “worn”.

Text when you can. Voice calls need a strong signal, and use a lot of battery. A text message can often transmit on a very poor signal, and uses minimal battery.

Test your overall battery use on a long day hike, before relying on it for a long trip.

Want to learn Navigation settings and cold weather tips for more battery savings?

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

Plush snow camping with a pyramid tent

A floorless, pyramid style tarp tent has some advantages over more traditional mountaineering tents when it comes to camping in snow and multi day ski tours. Let's learn a few clever tips for setting it up for maximum comfort, from the experts at Graybird Guiding.

The expertise and photos here (shared with permission) come from Graybird Guiding, a Seattle based guide company that not only leads some sweet ski trips, but also has an Instagram full of solid advice. Connect with them at their website and on Instagram. (Check out their hashtag #sknowmore for specific backcountry ski tips.)

Pyramid style, floorless tents have some advantages over standard floored tents when it comes to snow camping and multi day ski trips. Let's learn from some expert backcountry ski guides who have hundreds of combined nights sleeping with this set up.

What's great about pyramid tents in snow?

Lighter weight with larger floor area and more interior space.

You can customize it for space and comfort: dig a footwell for legroom, make a snow table in the middle for cooking, or using the slope of the hill as a backrest.

Better climate control: Lift up the bottom a bit if you need some ventilation, or bunker down from a storm by putting snow blocks on the outside.

If you rig it as shown below with ski poles, there's no center pole, which saves some weight and gives you even more space inside.

Because of the extra space and ventilation, it's safer and more convenient to cook inside your tent (even though this is still probably against manufacturer recommendations.) This makes a pyramid tent a popular choice for expedition climbing, like on Denali.

Floorless, so no more sleeping in a puddle of accumulated meltwater.

Speaking of melting water, no need to go outside to get snow; just grab a handful and put it in your stove, all from the comfort of your sleeping bag.

And, last but not least . . . you can pee inside your tent. (Hopefully in the opposite corner from where you collect snow for your meltwater. =^)

As shown in these photos, you're using your skis and poles as part of the tent structure. This works fine if you’re on a tour and moving along every day. If instead you're using the tent as a base camp, use buried “deadmen” anchors like sturdy plastic bags or stuff sacks to anchor the corners.

With your ski poles making an A-frame as shown here, you of course need to remove them the next day when you go skiing. Simply flatten the tent and put a few snow blocks in the middle to keep it from blowing away when you're gone.

Timewise, this typically takes two people about an hour, and a bit faster after you've done it a few times.

A few FAQs about pyramid tents in the snow . . .

How do they handle high winds and storms? Better than you might think. Using tents like this for the kitchen or “living room” is standard practice on Denali which of course gets some pretty crazy weather, so that gives you an idea. The snow blocks around the edge are crucial. Do a Google image search for “Denali cook tent” to see many photos of pyramid tents on expeditions.

How about sewing a “skirt” on the bottom to better seal out the weather? That is a common modification that many people do on pyramid tents. Adding a skirt gives more interior space, because you fully stretched out the walls and still have fabric to pile on snow blocks to seal the tent. Check out the photo at the bottom of the page. The tent from Black Diamond has a “skirt”.

What are some other options for anchoring the corners instead of your skis? Any sort of a deadman anchor that you can bury works. Maybe sticks that you pick up on the approach hike, or my favorite, a reinforced 1 gallon Ziploc freezer bag filled about 2/3 of the way with snow. Using a deadman of course makes your skis available to go on a tour and come back to a tent that is fully functional.

Can I use a center pole instead of the A-frame with the poles as shown below? Absolutely. When you’re staying in the tent, using your ski poles as support with no center pole is really nice. When you head out for the day and take your poles, install the center pole to keep your tent upright.

How does this work in faceted or unconsolidated snow? Not so well. It's harder to dig out of the blocks that you need to hold down the perimeter as well as forming the back rest and foot well inside of the tent. If you expect those kind of conditions, this may not be the best choice.

Here's how to set up a pyramid tent for snow camping

Here's a photo sequence and pro tips from Graybird Guiding showing how to prepare your campsite and set up your tent.

1) First, choose a gentle slope. This gives a backrest and added height so you can stand up inside. Next, use your ski as a guide / straight edge to start digging.

2) Remove snow in blocks, which you’ll use later. (Bonus: good practice for avalanche rescue digging.)

3) Stomp out pad with your skis. Without skins, point your skis downhill. If your platform is level, you won't slide.

4) Optional: Dig a footwell for even more interior space. Makes putting on your boots a bit easier. You can make a foot well because we’re using an A-frame support, not a center pole, see below.

5) Use your skis (or buried bags) to anchor the four corners.

6) Once the tent is anchored, bury the edges with the snow blocks you made earlier.

5) Rig an A-frame with four ski poles and Voile straps for better stability and more room. Not having a center pole in the way is really nice! Plus, check out the backrest which comes from digging into a slope, clever!

All done!

Check out this short (2:40) video that shows how all this comes together.

Sounds good, where do I get one?

Here are two of many options.

While different versions of this tent have probably been around for thousands of years, Black Diamond was one of the first (early 1990s?) to make a commercial model, which I think was the Megamid. Here's one of the newer models, the Mega Snow 4P, specifically designed for snow camping. Sleeps four people, weighs 1650 g (3 lb 10 oz). Note the “skirt” around the bottom edge; you can stack snow blocks on this to seal up the tent.

image: blackdiamondequipment.com

Here's a fancier model from Hyperlight Mountain Gear that's made from Dyneema composite fabric. Sleeps two, weighs a hair over 1 pound. Pricey but maybe worth it if you use it a lot.

image: hyperlitemountaingear.com

How to pack a cooler - pro tips

Nope, this is not a tip for alpine climbing, but it might come in handy next time you do a road trip. Here are some desert tested tIps for keeping your cooler organized, clean, and preserving your ice on longer trips where ice resupply is not an option. (Ever heard of “cooler soup”? It's something you don't want to try.)

Okay, let me say this up front: this is not a tip for alpine climbing, more for car camping and river trips. But everyone uses a cooler, and when you do, these tips may help a bunch!

If you're out for a night or two, then cooler packing is not a very big deal. However, on a longer, more remote road trip when you can't restock ice, or especially on multi-day whitewater river trips (a passion of mine) it's a lot more important. Rafters can be FANATIC about cooler packing and ice preservation - on a three week Grand Canyon trip, having ice left on the last day is the sign of a true pro. (I won't cover those very advanced tips here, because they don't apply to many folks.)

The following tips I’ve learned from a few expert river rats over the years, as well as some of my own trial and error. (And no, you don't need a $400 high end cooler!)

Give some or all of these tips a try on your next multi-day outing.

Freeze your own ice in plastic bottles

Freeze some plastic bottles for your ice supply, so you never have nasty melt water sloshing around the bottom of your cooler. One gallon Crystal Geyser bottles can be bought almost anywhere, are reasonably sturdy, and best of all are square-ish to fit nicely in a larger cooler. Mix and match water bottle sizes to fit the cooler you have. Empty two liter pop bottles are another good choice, and a bit more sturdy because they're built to handle carbonation.

Plus, when the ice melts, you have a big jug of cold water for drinking or cooking.

If you're don't have access to a freezer, block ice always lasts longer than ice cubes. However, most commercially available block ice you buy at stores is actually made from squished together ice cubes, and so it melts much faster than ice you freeze yourself.

Get resourceful on refreezing your bottles. If you're camping somewhere that's near a freezer, ask nicely, and you very well might be able to pop a few bottles in a restaurant freezer overnight to give you ice for the next few days.

(Side note on cooler sizes: bigger is always better for ice preservation. It's physics: the more mass of cold you have, the longer it's going to last.)

Use heavy duty shopping bags (or plastic containers) to keep food away from the ice

The last thing you want is your precious food taking a bath in yucky melted ice water, having delicate items getting crushed, or burrowing around to pull out the one thing you need that's worked its way to the bottom. Put all food into large container(s) or plastic reusable shopping bags.

Keeps food totally separate from any ice melt in your cooler.

Lets you quickly grab what you need minimizing the time the cooler lid is open, which helps a lot with ice preservation.

The downside is you lose a tiny bit of storage, but to me the trade-off is worth it.

Start with a couple of good quality reusable plastic shopping bags, like from Trader Joe's or Whole Foods. Note, these may not be completely waterproof, so you might want to test them first. If you follow the previous suggestion of keeping your ice in plastic bottles, the shopping bag(s) will pretty much keep your food perfectly dry. Try to be gentle with delicate produce in these bags; easier said than done.

For plastic tubs, go to a restaurant supply or “Cash and Carry” type store. Google “restaurant supply”. The containers are typically round or square, and come in lots of different sizes. The square shaped ones obviously fit better in a rectangular cooler. Bring your cooler with you to be sure the containers fit.

For my cooler, a 12 quart container fits nicely. Cost, about $12. My main cooler can fit two 12 quart containers side-by-side, with loose ice in the bottom and narrow frozen water bottles in between. If you’re taking a large amount of food, use two containers side-by-side. Try dinner stuff in one and lunch stuff in another, so you can just reach in and grab it and pull out the container you need. Doing this minimizes the time the cooler is open on a hot day, which helps a lot with ice preservation. Put fragile food, like fruit, inside the plastic tub, it can protect it a bit.

If the container stands just a little bit tall for your cooler, don't be shy about cutting off the top to make it fit. A power jigsaw is perfect for this.

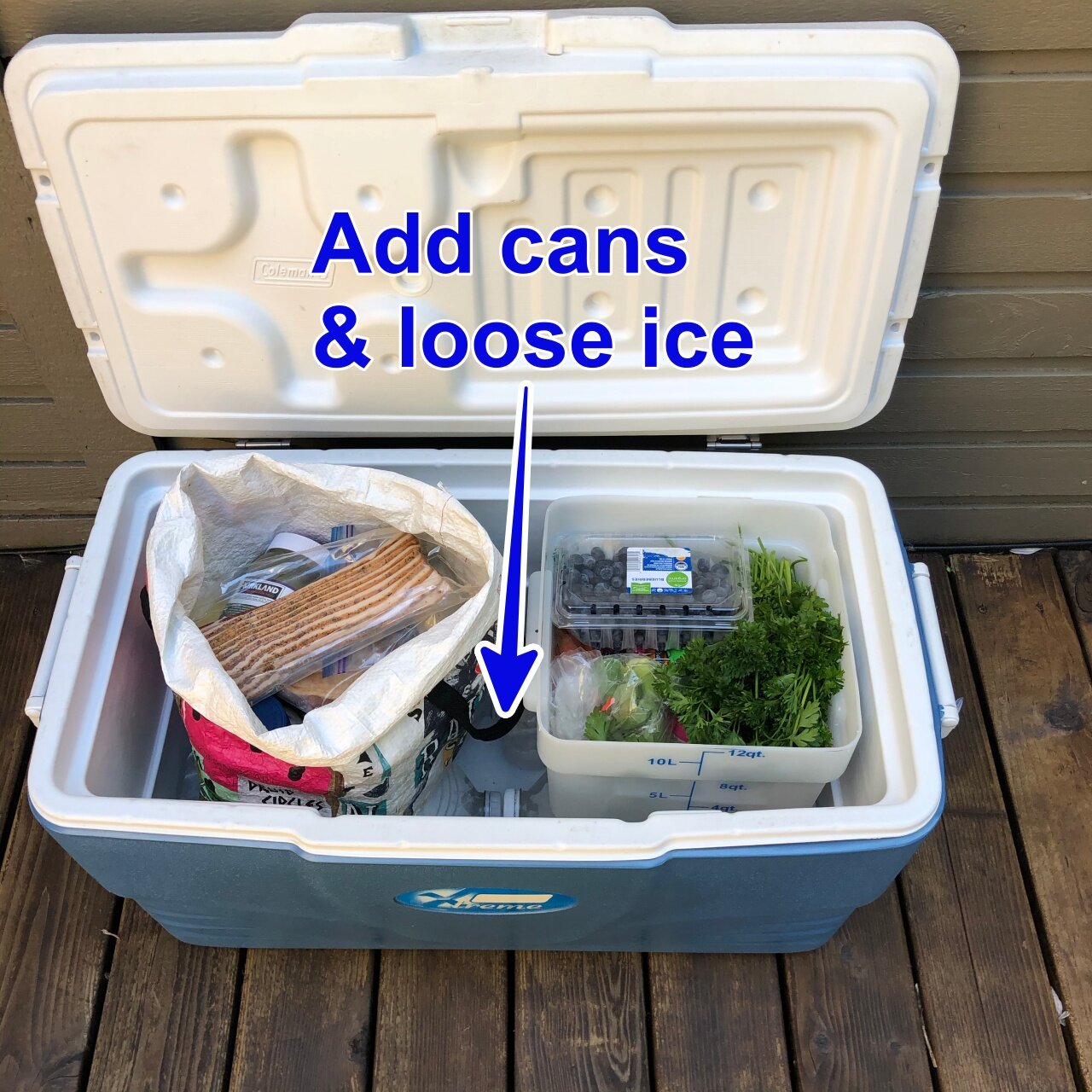

Getting ready to pack: Put the bottles in flat on the bottom and the food on top, fill the space between with loose ice cubes and cold cans. Fruit and veggies in the plastic bin (so they don't get squished), everything else in the shopping bag.

Transfer anything liquid from a “snaptop” into sturdy “screw top” containers

Salsa? Hummus? Forget those plastic tubs that they come in. When (not if!) the top comes off inside the cooler you’re going to have a TOTAL mess! (This is also known as ”cooler soup” =^) And yes, I've made that mistake; definitely not recommended.

Repackage into repurposed sturdy plastic screw top containers. Save the empty ones throughout the year, and by summertime you'll have a nice collection. Smaller rectangular containers stack really well and are space efficient. Sauerkraut containers (see the salsa photo below) are especially stout. Talenti ice cream comes in nice reusable screw top jars. Costco has a lot of items in large squarer screw top containers, such as mixed nuts.

Putting a paper container (milk, creamer, orange juice, etc.) straight into your cooler is also asking for trouble. It gets wet, the paper gets weak, and a puncture is highly likely. Instead, transfer liquids into sturdy empty plastic bottles. Tall skinny ones like this are good; they save on space and are easy to grab from above. (And yes, you can freeze milk and half-and-half.)

Eggs? I crack them into a sturdy plastic bottle, pour some half-and-half and give them a shake. They can be frozen, and give perfect scrambled eggs with zero mess once they are thawed.

Cover your cooler with wet fabric, and/or try to keep it in the shade

Take an old, light colored towel, get it wet, and drape over your cooler if it's in the sun, like on a raft or the bed of truck. This gives some evaporative cooling and helps with ice preservation.

If you want to really get fancy you can make a “cozy” for your entire cooler out of mylar coated bubble wrap, called Reflectix. This also keeps direct sun off of your cooler and on a multi day trip can really help with preserving ice.

The main concept is to try to avoid opening your cooler in the heat of the day. When it's cool in the morning, pull out everything you need for lunch from the main cooler and maybe transfer it to something smaller.

Pre-chill or freeze as much food as you can

Coolers are good at keeping food cold, but not so good at making food cold. Avoid putting any warm or room temperature food, especially drinks, into your cooler. Buy your canned beverages already cold, or pre-chill them the night before in another smaller cooler or main fridge and then add to your main cooler the day of your trip. Try to freeze all meat before you put it in the cooler. (If you can prep slice the meat and even put a marinade on it before you put it in the cooler, bonus points for you. The vacuum sealer can be your friend here.) What else can be frozen, like pasta sauce, milk or scrambled eggs? Freeze everything you can.

On a related note, you can pre-chill your entire cooler. Take a few sacrificial bags of ice, put them in the cooler the night before your trip, and then load your pre-chilled food in the day you leave. (If you have access to a walk-in freezer or refrigerator, that makes it a lot easier.) This also works with a smaller flexible fabric type cooler, simply put the whole thing in your fridge or freezer the night before.

Bring an extra cooler just for ice

If you're on a long trip and you have the extra space, consider bringing an additional large cooler just for ice. As the ice melts off in the main food cooler, you can replace it, plus always have clean ice available for beverages.

For the “ice-only” cooler, duct tape the top closed to help eliminate any air drafts, and also reduce any temptation to open it before you really need to.

Bring an extra cooler just for drinks

If you’re planning a trip with lots of, ahem, beverage consumption, a good approach is to have one cooler for food that gets opened only at mealtimes, and an entire separate cooler for beverages, that has mostly loose ice. This keeps thirsty people from constantly opening and closing the main food cooler.

Empty space means warm air, which means your ice is going to melt faster. Ice is cheap. Buy an extra bag or two and fill up the whole cooler completely. If possible, pre-chill all beverages before you put them in the cooler

Add a cover inside your cooler

Cut a piece of closed cell foam pad to fit snugly inside of your cooler, to add a extra insulation. A folded wet towel put inside the lid does much the same thing, preventing your ice from getting blasted by hot air. This can also keep your food away from condensation or any meltwater.

Go a creek nearby? Put your cooler in it!

If you have a cold stream / lake nearby, keep your cooler in it. Of course be sure it doesn’t float away or tip over, that would be a problem. 😉

Did someone give you block ice? Put it in a dry bag

If you're on a river trip and someone donates a block of ice to you, you can put it inside a dry bag, and then put the dry bag in the cooler. This keeps all the meltwater contained.

Try dry ice

Consider using dry ice underneath your frozen water jugs. That can get you an extra day or two of cold. Note that some food does not do well stored with lots of dry ice, like many vegetables. This is more of an issue if you use all dry ice in your cooler. If you have mostly frozen water jugs and a little dry ice, it's gonna be fine.

Divide your food for sections of a longer trip

You're lucky enough to be on a LONG river trip, an extended desert adventure, or anywhere where are you can’t restock ice. Here's one approach:

You need two coolers. Ideally, one is large and well insulated.

Separate your food carefully (I mean carefully!) into the first half of your trip and the latter half of your trip. (Let's say we have a 10 day trip, so call days 1-5 “cooler 1” and days 5-10 “cooler 2”.)

Pack your food (using the tips mentioned above) in each cooler. Make cooler 2 the larger and more insulated one, so you can hopefully pack in a bit more ice.

On cooler 2, duct tape the top closed and write on the tape: “DO NOT OPEN until day 5!” Maybe even make a reflectix cover for it as mentioned above, keep it in the shade as much as possible, and whatever you do, don’t open it until all the food in the first cooler is used up. Simply not ever opening cooler #2 until day 5 is the biggest thing you can do to preserve the ice. The duct tape reminds people not to even think about opening it, as well as sealing up any micro air leaks.

Use 2 carabiners to fix a broken backpack waist belt

A broken waist belt buckle can be a substantial problem on a remote trip with a heavy pack. However, with this clever tip, you can probably fix it with just two carabiners.

Breaking the buckle on your backpack hip belt is pretty common, and can be a rather serious problem.

Here’s a very crafty way to fix this, courtesy of Alpinesavvy reader Andy Sorenson. (Andy happens to be a mechanical engineer and product designer, which sounds like the perfect skills to have when you break something in the woods. Connect with Andy at mindsparkdesign.com.)

Arrange two carabiners as shown below, thread the webbing through them, and cinch down. The friction from the carabiners holds the webbing snug. (Depending on the width and slickness of your webbing, your mileage may vary; it worked fine for me. )

While this works as a temporary repair, having an inexpensive and lightweight spare buckle in the repair kit is a fine idea if you’re on a longer trip.

Top reasons why “hydration systems” are Less Than Ideal

Lots of people use water bladders, but they have a host of downsides that are rarely considered. Here's a list of why water bladders really do “suck”.

Everyone agrees that keeping properly hydrated is important in any endurance sport. But do you really need a so-called “hydration system” to do this? While water bladder / reservoirs can work for mountain biking and day hiking, they have a host of downsides you may want to consider before you take one on your next long hike, trek or alpine climb.

The tubes can freeze.

There are many delicate parts (tubes, bladders, mouthpiece bite valves) that can easily break or malfunction, and they’re hard to repair in the field.

They have lots of hard to clean cracks and crevices where funky microorganisms can grow.

They’re hard to fill, either from streams or with snow.

It’s difficult to monitor your water consumption and see how much you have left.

It’s hard to share water with others.

Depending on the design of your pack, you may have to empty out a good chunk of it to remove and refill the reservoir.

The mouthpiece can easily drag in the dirt when you put your pack on the ground, yuck.

You can’t use a reservoir in camp as a cup for hot drinks.

You can’t put hot water in a reservoir and put a sock over it at night, to help dry out wet socks.

They’re very expensive compared to a simple water bottle.

Bonus reason: Unless you’re in some sort of a race/competition, are you REALLY in that much of a hurry that you can’t stop for a minute or two and drink some water?

So, how to stay well watered on the go? A simple water bottle.

Get a small ultralight mesh bag and attach it to your pack shoulder strap. (Search Etsy for “backpack water bottle holder”, or try this Etsy store.

Put a water bottle in one of the stretchy mesh pockets on the side of your pack, a feature of many packs designed for backpacking. If it's hot, start your trip with larger bottle(s) inside your pack, and refill the small bottle at breaks. This lets you drink on the move as effectively as a bladder system, with none of the cost and hassles.

Don't get a Nalgene bottle, those are too heavy (about 7 ounces empty). Simply re-purpose most any empty water or juice bottle. Smart water bottles are popular, they are tall, skinny, and have fairly sturdy plastic. Personally, I am a fan of the 20 ounce Gatorade bottle.

Oh, and, check the water bottle aisle next time you’re in REI. Camelback sells, you guessed, it, a simple water bottle (complete with large Camelback logo.) A tad ironic, no?

Related story: A friend of mine went on a trekking expedition to Tibet. The trekking company explicitly told everyone on the trip NOT to bring water reservoirs with a tube. Reason: The trails were also used by pack animals such as yaks. Yaks poop everywhere. The sun and low humidity dries out the yak poop, and then the poop pulverizes into tiny particles from the feet of people and animals. The floating yak poop powder then settles on, you guessed it, your drinking tube, YUCK! They found that many Westerners were getting sick on their trips. When they had guests change to a simple water bottle, the illness rate went way down.

Finally, here's what world-class alpinist Steve House thinks about water bladders.

(Can you imagine planning and saving money for months for an expedition, traveling halfway around the world to a remote serious mountain, and then bailing because your water bladder leaked all over?!)

Use a tarp for a quick snow shelter

Carrying a tarp is not only for shelter; it does extra duty as a first aid and rescue tool. Here's a slick way to make an emergency snow trench shelter with a tarp.

This tip comes courtesy of the Jackson Hole Outdoor Leadership Institute.

The photos were first published in this Facebook post.

Carrying a lightweight tarp as part of your emergency shelter system is an excellent idea for lots of reasons. In addition to the obvious tent-like shelter to sleep in, here are a few other options.

Lunchtime quick shelter for you and a small group (sit on your packs and pull the tarp over you.)

Package an injured person and drag them out in snow

Outer layer of “thermal burrito wrap” to package an hypothermic or injured patient with foam pads and sleeping bags / warm clothing while you wait for rescue in a cold environment

Extra layer over a simple bivy bag, offering more protection for your upper body and some covered room to move around

For today's post, it's a key component of a snow trench winter shelter.

The basic concept is simple, and the photos below show it pretty well, but here's a step-by-step. (The photos below are for people with ski touring equipment, but if you don't have it you can improvise.)

Dig a rectangular hole that's wide enough for you and your ski buddy, and about 4 feet deep. (If the snow isn't that deep, you can excavate down to bare ground and then build up walls on three sides.)

Place your skis across the top (If you’re below timberline and don't have skis, branches would work also)

Put your tarp over the skis. ( A 7’ by 9’ tarp is about the minimum size you can use; ask me how I know this!)

Use your ski poles (or branches) to anchor the four corners of the tarp.

Pack some around the edges of the tarp.

Dig a separate access hole, and carefully build an arch / hole so you can get in and out of your trench.

If you have an proper sleeping bag and sleeping pad, you're all set. If you don't, you better dust off your bushcraft skills, and go collect a bunch of conifer boughs to place under you for insulation, and on the side to keep snow from falling in on you.

There you go! Fast, reasonably comfy, and constructed without any advanced igloo building skills or getting sopping wet from trying to dig a snow cave.

photo: https://www.facebook.com/JHOutdoorLeadership/posts/1920166718037956

photo: https://www.facebook.com/JHOutdoorLeadership/posts/1920166718037956

There are lots of good quality tarps out there.

Ski rescue sled tarps

If you spend a lot of time backcountry skiing, you might want to carry a rescue tarp. Use it as a quick lunchtime shelter, a more serious overnight pit shelter, and a toboggan-style rescue sled. Check out the one below, made in Seattle by High Mountain Gear.

Use the discount code ALPINESAVVY10 to get a 10% discount from High Mountain Gear.

High mountain gear ski guide sled tarp. Photo: https://highmtngear.com/

High mountain gear ski guide sled tarp. Photo: https://highmtngear.com/

Here's a tarp I have that I like a lot, the Pariah Sanctuary Sil tarp. The main thing I like is the price.

Note that the link below will show you tarps in several shapes and sizes. I have the 8’ x 10’ “flat cut rectangle”. The sewn tabs at the the 16 tie out points are well made, and it comes with all the goodies you need to set it up, including six ultralight stakes, 60 feet of 1.5mm Dyneema guy line and a carrying stuff sack.

(And note how to pronounce the name = “Pariah” is pronounced like the woman's named, “Maria”.)

A true story: drinking water trailside in Nepal

Think about it. Why are you in such a hurry in the backcountry?

Two trekker guys are hiking on the Annapurna circuit, a 200+ km trail in the beautiful Nepal Himalaya. One of them has a water bladder in his pack. The two guys stop for a break next to some porters who are carrying loads of supplies up to higher villages. It turns out that one of the porters speaks some English. A conversation begins.

The porter asks, “What is that tube coming out of your pack?” The trekker guy replies, “It's for drinking water.”

The porter looks a little puzzled. He asks, “Why not use a water bottle?” Trekker guy says, “Because the tube lets me drink while I’m walking.”

Porter: “Why do you want to drink when you’re walking?” Trekker: “So I don't have to stop as often.”

Porter: “Why don't you want to stop?” Trekker: “So I can walk faster.”

Porter: “Why do you want to walk faster?” Trekker guy, pausing a moment: “So . . . I can walk more farther in a day and finish my hike sooner.”

The porter pauses. He talks with a few of his friends in Nepalese and they shrug their shoulders and chuckle. The porter turns back to the trekkers.

The porter says, “What do you think of Nepal?”

The trekker takes a deep breath, looks around at the stunning mountains, and back to the porter. He says, “This is really a trip of a lifetime for me. I've been dreaming of coming to Nepal for years, and it's one of the most beautiful places I could ever imagine."

The porter gives him a big smile. "I agree", he says, "it is very beautiful. That’s why there's no need to rush. You will be here probably just once in your whole life. So, my friend, take your time, drink your water slowly, have lots of breaks like the one we are having now, and enjoy your trip, these mountains and my beautiful country. Namaste.”

"Lost in the Gorge" - a cautionary tale

This account of a lost person (shared with her permission) is instructive at many levels. As you read it, make some mental notes about her good decisions and perhaps not so good decisions. Could this happen to just about anyone? Answer, yes.

This story is an account of a lost person in the Columbia River Gorge, Oregon. It was originally printed in the November 2014 Mazamas bulletin.

It’s shared here with the permission of the author, who wants as many people as possible to learn from her experience and hopefully avoid a similar one.

Pam did many things right, and a few things not-so-right. As you read this, make a short list of what you think these things might be.

Probably the single most important thing she did right was to be able to determine her latitude longitude coordinates from her phone, and transmit that information to 911. This is a vital skill for any backcountry traveler, yet many people who carry a smartphone with complete GPS capabilities don't know how to do this. We cover various techniques in this tip here.

Lost in the Gorge

by Pam Monheimer

I admit it; I was the woman lost in the Columbia River Gorge on January 29, 2014. I had been trained in mountaineering, avalanche basics, CPR and Mountaineering First Aid (MFA). At first I was embarrassed and horrified that my friends and my Mazama acquaintances would learn of my debacle.

When I was finally located, rescued, been transported out and, at 11 pm, arrived at the Sheriff’s van to be debriefed, I was sick to see that the Angel’s Rest parking lot was packed to capacity with rescue teams, ambulances, police cars, and, of course, the four news channel crews. I caused a lot of people a lot of trouble and worry. I am sorry. I am grateful to those who helped rescue me, and to the Mazamas for providing me the mountaineering training that kept me alive. I want to tell my story as I think I can help fellow hikers and perhaps save a life, especially with colder, wetter weather and shorter days upon us. As I’ve been told more than once, “nobody plans on getting lost.” Not even on a short hike.

In the past 18 months I have hiked over 2800 miles, climbed atop and skied numerous mountain peaks in the Cascades and Olympics. I have hiked and climbed the entire Haute Route in France and Switzerland. Getting lost for me in the Gorge is like getting lost in my own backyard. I know it like the back of my hand. When I drive Highways 84 and 35, I can name all the mountains, hills, waterfalls and trails to myself. The Columbia River Gorge is in my DNA.

I frequently hike with friends and, as we travel at different paces, it is not unusual for us to split up with plans to meet at a designated place and time. I was hiking with my friend, William, a world-class runner and climber with whom I often hike both the Gorge and Mt Hood. It was 34 degrees with a light rain falling. We had a few hours to spend hiking in the Gorge. We started out together in the late morning in a remote area a few miles behind Angel’s Rest. We were in a place I’ve hiked a more than a dozen times before. William and my vizsla puppy, Tüz, went running ahead, and we planned to meet back at my car at 2:30 p.m. I was listening to a book on my iPhone and was so engrossed I didn’t realize how much time had passed. When I noted the time, I realized I needed to quickly head back. I cut through the woods, off trail with my compass in hand to get back to the main trail that would take me back to my car.

After 20 minutes I still hadn’t found any trail. I thought I was in a totally unfamiliar area, didn’t recognize any surroundings and was among fallen trees, deep brush, and on a very steep slope. The light rain had turned heavier and it was becoming quite breezy. I was worried, I knew I couldn’t be very far from a trail, but I was scared enough with the changing conditions that I called 911 then quickly lost the connection, as cell service was iffy at best in the area. I called twice more and finally made contact with the Multnomah County Sheriff, as my call had been answered by Clackamas County Emergency. I explained that I was in Multnomah County.

After describing my location, I emailed and texted my exact coordinates from my GPS at 2:39 p.m. The sheriff assured me help was nearby telling me, “they had found my car, William, and Tüz, and that the whole world was coming to help find me.”

The most important thing I did after that emergency call was to stay put, a very important Mazama lesson. Search and Rescue had my exact location. I paced and did jumping jacks to stay warm. In another text the sheriff asked me how much battery time was left on my phone now; 25 percent, yikes, it was over 50 percent just a few minutes earlier. Once my situation hit the news, friends and family called, texted and sent Facebook messages. By 3:15 p.m. my phone was dead.

The breeze had blown into the famous Gorge gusts. Luckily, I was wearing the correct clothing and boots for the day. I had a waterproof jacket, pants and Gore-Tex lined hiking boots. I was also wearing a down sweater underneath. All that was fine for the first few hours, but now it was 4:30 p.m. and I was soaked, shivering and darkness was settling in. How long could my rescue take? Rescue had had my coordinates for over two hours.

I went into survival mode. I dug a hole for shelter next to a large downed tree with my gloved hands, filling it with leaves, small branches, pine needles and anything else my filthy, frozen hands could carry. I then attempted to build a cover made from larger branches to try to shield myself from the rain and wind until rescue arrived. For a few desperate brief moments I considered making a run for the trail in the remaining daylight. Had I done so, I fear there might have been a less fortunate ending to my adventure. It was odd to be alone in the ebony forest with only the sound of the wind and rain. I had no fear of being alone, I had passed survival training.

As I lay in my dugout in the pitch black, no moon powerful enough to shine through the awful inky, rainy, gloom, I realized I did not have my “10 Essentials” that should be taken on every hike. BCEP and the Mazamas had drilled into my head over the past year that those essentials should always be in my pack. Just a week earlier I was sitting on the summit of Mount St Helens with my larger backpack filled with these 10 Essentials. I didn’t think that it was necessary to repack my smaller pack for a few short hours of hiking, but then again, I hadn’t planned on getting lost either. Thus I had no headlamp, no extra clothing or waterproof matches, or any other useful tool that might help me remain safer and warmer until help arrived. All I had was my small daypack with a slowly decreasing amount of water and a lone protein bar.

Eventually I had to stop the jumping jacks and pacing, which had kept my muscles moving. The darkness and uneven terrain could prove treacherous. I lay down in fetal position in my wet, muddy hole to try and stay warm. I hugged the earth for warmth. My teeth were chattering so hard I had to put a cloth between my teeth and by now I also had a raging headache. After a while I realized I couldn’t move my curled legs or arms, they were both totally cramped. My mind was playing games, I didn’t know if I was awake or asleep. So this was hypothermia, I thought.

It had been five hours since I realized I had become lost and placed my 911 calls. Where was the cavalry? I thought something had gone wrong, perhaps the GPS coordinates had been incorrect, there had been a landslide, or worse a change in plan with daytime rescue. I needed to stay alive until morning so I could get myself out in the daylight. Then I had the realization that I might not make it. I was too cold to cry. I thought about my family and my friends. All the small stuff I wasted time and worry on. All the things I never did or said. I truly thought this would be where I died. By 7:40 p.m. I was so darn miserable but something inside me refused to give up. It took all my strength, balance and my huge pain threshold to stand up, as I knew I had to move if I were to stay alive. I jumped in place and screamed “I am not going to die here!”

In the distance I saw faint light. I remembered my GPS watch had a backlight. I flashed it as I jumped. I was screaming help and hello to no avail, as the storm was too loud, and flashing my light. A few minutes later the faint light came closer. I waved my light frantically and the rescuers waved theirs back. It took over 30 minutes for the five-man search and rescue team to reach me. I learned there were four teams that had started out at different points looking for me as well as a sheriff’s “quick response team” comprised of two runners who were out looking for me. It was the quick response team that found William and Tüz. They ran nearly 15 miles looking for me and as I later learned, they came within 1.5 city blocks of where I was calling for help.

My rescuers went into action, following the same protocols I had learned in Mountaineering First Aid. I was so relieved and grateful to this group who saved me. They carried the largest packs I’d ever seen. They offered me blankets, dry clothes, water, food, etc. I was too cold and shivering so hard I couldn’t fathom changing clothes; they persisted and then wrapped me in the blankets. They then had to study maps to figure the safest way out. We went through thick brush, fallen trees and down a steep slope and we still had to walk a few miles to one of the two vans that had made it to the fallen tree a mile from the start of the trail. One of the vans then got stuck in the mud, which added more than an additional hour to my evening.

I used the time to get to know this quality group of volunteers who had braved the elements to find me. Some were still in high school. I learned that they had to pay for their own gear and have made it a personal goal to support Portland Mountain Rescue with an annual donation.

William and I went back a few days later with the sun shining, a layer of fresh snow dusting the trail, and a GPS unit with my coordinates plugged in to see where I had gone wrong and “get back up on that horse right away.” I was fearful of going off trail again and didn’t want one scary incident to ruin my love of exploring.

It was bizarre to see the shelter I had built myself, and understand that I had done the right thing by staying put, as the terrain was steep with lots of fallen trees. I’ve learned to carry orange trail tape for when I want to explore new areas and mark turns, and I always bring my 10 Essentials. I have a set of those important, potentially life-saving items in every backpack I own. I never leave home without them.

Emergency fire starter - bicycle inner tube

This emergency firestarter is free, very lightweight, completely waterproof, and gives you a nice steady burn for at least five minutes. Oh, and be sure to stay upwind.

A bicycle inner tube cut about 1 inch wide works great for a firestarter. It’s free, can’t soak up water, weighs nothing, packs well, and burns great for a few minutes, enough to catch damp tinder.

Only problem is that it stinks, so stay upwind. Yes, it’s toxic and nasty, but it’s for emergency purposes only, not as a regular go-to fire starter. Punctured tubes are free for the asking at any bike shop.

Wrap two “rubberbands” around a lighter so you always have your flame source and firestarter together.

Wheel style lighters don’t work when wet. One solution: Cut a small bit of plastic bag, put it over the business end of the lighter, and then secure it in place with one of your rubber bands.

If you're looking for a great fire starter for everyday use, you can read about one here.

Tactics for the 4am pee

Every mountaineer has faced that 4 AM decision: Stay in my bag until my eyeballs get yellow, or leave my warm tent, go outside and take a pee? Fortunately, there’s a middle ground.

Altitude, cold, and maybe Diamox can all cause you to urinate more frequently when in the mountains. Snow camping, at night, and stormy weather are all complicating factors, especially at the same time. Stay in your warm sleeping bag and try to hold it, or step outside into the gale to take a pee? It's a tough question all mountaineers face.

Fortunately, there’s a fairly easy solution.

While it’s mandatory gear for a big expedition, a dedicated pee bottle probably won’t be carried on a shorter trip. Solution: a 1 gallon Ziploc freezer bag.

Lightweight, takes up no room in your pack, and can give you relief when you need it most. Yes, 1 gallon is probably more than you need, but you can share the bag with your tent mate. (Word has it that ladies find a bag easier to use than a pee bottle.) Put the bag in the tent vestibule after use in case the closure is not as strong as you thought.

Bonus - The same 1 gallon Ziploc freezer bags also work great as buried snow anchors for your tent. So, you might as well bring a few!

Related tip: If you’re on a longer expedition and you have a designated pee bottle, it will smell pretty ripe after a few days, especially when you open it in the tent. For a pee jug odor preventor, before you settle in for the night, put 2 iodine tablets (the same as for water purification) into the empty pee jug. The iodine kills the bacteria that cause the odor.

Below is one good option for expeditions: The Nalgene 48 ounce flexible Cantene.

How to fix a ripped tent

Got a rip in your tent? Here’s how to fix it with tape, mosquito netting, and adhesive.

Here’s how to fix a rip in your tent.

Put duct tape on the outside, add seam grip (or similar liquid adhesive) to the inside, put on some mosquito netting on the wet seam grip, then put on another layer of seam grip. Once it’s dry, it’ll be stronger than the original tent.

Granted, these are not items you are likely to have on a short climbing trip, but you can take care of it when you get home. On a longer expedition, this may well be repair gear you want to carry.

This tip is from the excellent book, “1001 Climbing Tips” by Andy Kirkpatrick

Conditioning hikes - Tips for clothing, food and navigation

Heading out on a conditioning hike? Put a little thought into your clothing, food, and navigation to get more out of your day.

You can get a lot more out of your next “conditioning hike” (typically more than 8 miles and 3,000 feet elevation gain) than just aerobic exercise. Consider working on your clothing layers, food/water intake and navigation skills, in addition to getting a workout.

Clothing

Make a point of going out on training hikes on some of the wettest days. If it’s really storming, stay closer to home. Use these soggy trips as a way to test your clothing systems. Try different combinations of clothes, top and bottom.

Try starting out with less clothes than you think you need. You may be happily surprised at how little you need to stay warm. Remember, it’s often okay to be a little damp next to your skin, provided you’re moving and are staying warm. You may find that you sweat too much in that 3 layer Gore-Tex jacket, shortie gaiters work just fine even in knee deep snow, or that a base layer and light windshell are all you need when hiking fast.

Nutrition

On conditioning hikes, try different types of food and see what keeps your motor running. This is especially useful if you’re experimenting with carb-type energy drink mixes or eating energy gels (Gu) for 8 hours straight.

Start your food experiment right when you get up. Eat the same meal you’d plan for a multi day climb, which might be a couple of granola bars at 4:00 am or some instant oatmeal. (Personally, I find that instant oatmeal does not give me much energy, but adding a couple of scoops of quick dissolving whey protein powder improves things a lot.)

Did you finish your hike with 1 pound or more of extra food? You’ll want to bring less next time (an “extra” food ration of a 1 oz. Gu packet or two are all you really need).

Remember the yummy summit snack!

By making your food intake on a training hike day match what you’d really eat on a climb, you’ll have a much better idea what your body needs to operate well in the alpine world.

Navigation

Even on hikes where you know the trail perfectly, bring a topo map, compass and a GPS app like Gaia GPS on your smartphone. Plan on taking some extra time to practice navigation; it’s not a race out there.

When you get to a viewpoint, orient your map to the terrain (for example, if you’re facing south, hold the map so the south edge is furthest away from you.) Doing this aligns the map with the real world features you see in front of you. Identify terrain features like ridgeline and gullies and match them to your map. This helps you develop the skill to see contour lines and visualize what they represent in the real world.

Practice estimating distances. Pick out some real world features, guess how far away they are, locate them on your map, and use your map scale bar to determine the actual distance.

When at a known position on the map, use the map to determine your UTM coordinates. To do this, you need a UTM grid printed on your map, and the knowledge of how to estimate your position using this grid. (Learn more about UTM coordinates from this video.) Then get a GPS waypoint and see how close the coordinates match (within 200 meters is pretty good.)

Then, try the opposite. Pretend you don’t know your position on the map, get a GPS waypoint from your phone, and then plot that on your map and see if it matches your current location. (You can print maps for free with a UTM grid at caltopo.com. Learn how to use Caltopo from this video.)

As the saying goes, if you always know where you are, you can’t ever be lost. Get into the habit of keeping the map handy, referring to it often, and keeping track of your position. At any point on a hike or climb, you should be able to pretty much put a finger on your specific location on the map. Consider drawing your position / route on the map at every break, more often if traveling off trail in challenging terrain. Use a colored pencil for visibility.

Creek crossing safety

Creek crossing is a common and potentially dangerous part of many mountaineering approaches. Here are some simple techniques to lower the risk.

photo: pcta.org, taken by Justin “2t” Helmkamp

Crossing a stream or creek is often a part of mountaineering approach hike, and it’s potentially one of the most dangerous parts of the climb. Here are a few tips (gleaned from several whitewater rescue courses I’ve taken) that can make this a bit safer.

Always face upstream.

Wear shoes. Yes, your shoes will get wet, but your footing will be much more secure.

Using poles (trekking poles or sturdy sticks), one in each hand, is the single best way to improve your balance in a crossing. Not enough poles for everyone? Toss them back once one person is across.

Take some time to scout. Look upstream or downstream to check for a friendlier crossing if you don’t like what you see when you first arrive.

Snowmelt streams are usually lower in the morning. Consider an early morning crossing to have lower water levels.

Water depth rule of thumb: if the water is moving fast and over your knees, you should take extra caution. Note that this rule does not apply equally to taller/shorter team members, and the speed of the water has a great affect on the potential hazard of the crossing.

Be extra careful on snow bridges. Punching through the snow and into the creek can be deadly.

Cross in a three person triangle – Moving in unison across the creek as a group can add stability to everyone. Make a triangle, with the “point” being the largest person, who faces upstream. The point person has a pole in each hand. The other two members of the triangle have a pole in the outside hand and one hand on the shoulder or pack of the point person. The larger point person makes an eddy of sorts with their legs, providing an area of slack water for the inside legs of the two back people. If the back people start to slip, they can grab the other members on their triangle and hopefully recover.

Remove your pack waist belt so you can quickly ditch your pack if you fall in. On a really challenging crossing, you may want to completely remove your pack. Have another stronger person carry it, or maybe rig a clothesline loop rope across the creek and ferry the packs across one by one.

Try to find a crossing point that has a friendly runout; if you were to lose your footing and fall in, you’re not going to be swept over a waterfall, or into dangerous rocks or a log jam.

See this this nice article at PCTA.org for a more detailed look at this important skill.

Estimate time to sundown with your hand

Wondering how long it will be until the sun sets behind that ridge? The answer is at hand. =^)

When it’s late afternoon and you’re wondering if you should make camp or not, use this trick for estimating the time until sundown.

Extend your arm and your fingers toward the sun, then bend your wrist. Each finger represents about 15 minutes. Leapfrog your other hand if needed to estimate times more than 1 hour.

This trick works if the horizon is flat or a mountain ridge line, it doesn't matter. Note this is an approximation, and varies a bit depending on your latitude.

In my neighborhood in the Pacific Northwest, a good rule of thumb to total darkness is add about 30 minutes to the sunset time. So, if your hand (or your smartphone) tells you sunset will be in one hour, you have about one hour 30 minutes of usable light. This will depend on your latitude, test it in your local area to be sure.

The same applies to usable light in the morning; subtract 30 minutes from sunrise time to find the first usable light. For alpine starts, this can help you plan your wake up time, as being on more technical terrain when you can see where you're going is usually a good idea.

Example: from your camp, you have an hour of easy walking on a trail before some technical climbing begins. You and your partners want to have a fairly leisurely hour to get ready after you wake up. Your phone's weather app tells you that sunrise is at 6:15am.

Subtract 30 minutes from 6:15, and you get first usable light at 5:45. Subtract two hours from that, and you get an approximate wake up time of about 3:45 am.

Two ways to melt snow with solar power

No, you don’t always need that $220(!) MSR Reactor stove to melt snow at your high camp. Try free solar power instead.

Melting snow for water is a time and fuel consuming part of winter camping and many overnight snow climbs. If you have a base camp and the sun is out, try passive solar power to get some extra water. You do need a large black garbage bag for this to work, which is something you probably want to have in your pack anyway, because it serves lots of other purposes, like a pack cover, glissade device, and emergency shelter.

Here's two methods to melt snow via solar power.

First, the simplest method, if you have some exposed rocks nearby. Put some snow in a black garbage bag, secure the top, and put the bag on the (somewhat) warm rock. This should melt the snow in an hour or two.

Second, slightly more complicated, works on snow when you don't have any exposed rock.

Find a slight downward slope on snow.

Make a slight concave surface in the snow, slightly larger than your garbage bag.

Lay a sleeping pad on the snow, and put the garbage bag on top of it.

Pack some snow around the edges of the pad and bag so it doesn't blow away.

Put a small amount snow on the surface of the bag in a shallow layer, and add a picket to make a “V” for the meltwater.

Put a cook pot at the bottom underneath to catch the drips. Monitor, and add more snow as needed.

From the always awesome book, “Glacier Mountaineering: An Illustrated Guide to Glacier Travel and Crevasse Rescue, by Andy Tyson and Mike Clelland.

Survival shelter for an unexpected night out

Looking for a lightweight, inexpensive and versatile emergency backcountry shelter? Using this common item is a great choice.

In the book “Analysis of Lost Person Behavior” author William Syrotuck analyzed over 200 rescue cases. He found that 11% ended in fatalities, and three quarters of those people who died generally did so from hypothermia, within the first 48 hours of becoming lost.

So, to look at these statistics in a more positive way:

If you’re lost, you have an approximately 90% chance of surviving.

If you can stay alive for 2 days and minimize the chances of getting hypothermia, your survival odds increase to around 97%.

This tells us that carrying some kind of emergency shelter is an excellent idea.

But what, exactly does that mean? A one person tent, a tarp, a bivy sack, maybe even a bothy bag, which is kind of a British combination of all three? Or something more minimal?

If you have a reasonable chance of spending a night out, you probably want something fairly substantial, like a bivy sack and tarp. But, if you're after something to keep in your hiking day pack for emergency use only, something lighter which takes up less space is probably a better choice.

For emergency use, go with simple: a heavy duty garbage bag. Cost: about $1, weight, about 5 ounces / 140 grams.

As a survival shelter, cut a small slit in the side end for your head, see the video below. If you're about average height, you can probably crouch over and get most of your whole body inside the bag. If you're tall than that, you might want to bring two bags, one for your feet and one for your torso and head.

Also, the bag serves as a rain cover for your pack, and easily converted into a poncho if you cut a hole for your neck and arms.

Be sure and get the heavy duty “contractor clean-up bags”, that are huge (typically 43 gallons) and 3 mil thick. (Side note: a “mil” means one 1000th of an inch, and is a standard in the United States for measuring the thickness of plastic. It’s not a millimeter or a milliliter.)

At the big box hardware stores, you usually need to buy a humongo box of 50 of these, so if you know anyone who’s a builder you could ask them for a couple of extras. Or, they’re available on Amazon as a more reasonably sized box of 20.

After some hunting around, I was able to find some that are orange, better for increased visibility, unfortunately available in a pack of 50. So I've been sharing them with various climbing friends and students over the years. Try a Google for “orange 3 mil 42 gallon contractor trash bags". I found mine from plasticplace.com.

Many backpacks have a water bladder pocket, or maybe a pocket to hold a foam pad as part of the suspension. You can slip the bag in this pocket; you're not notice the weight and it’ll always be in your backpack.

These are the bags I got from Amazon:

Here is a nice short video from the excellent MedWild YouTube channel on making a quick emergency shelter with a garbage bag. Note that he cuts just a small hole in the SIDE of the bag, which lets you breathe and see, but keeps your head protected.

Many people want to cut a hole for your head in the top of the bag, which keeps your head exposed. The hole in the side is much better. Here's a screen grab from the video showing this simple technique.

image: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=baTeliYY9lc&feature=youtu.be

And here's the whole video:

What about mylar “space” blankets or mylar bivy sacks?

Lots of people carry these for emergency use. But they have a few issues:

Yes, they can reflect some of your body heat back, but if you're getting hypothermic, there's not much heat being generated in the first place. If you have proper clothing on, that should be doing its job of keeping heat close to your body.

If you have the mylar against your bare skin, the blanket will conduct the heat away from you into the cold air. The same thing happens if you put it on bare ground, heat conductivity from your butt into the earth.

The very inexpensive ones are extremely fragile and start ripping if you sneeze on them, so don't even bother buying those.

Most emergency bivy sacks are pretty much non-breathable, so you can expect to get a fair amount of condensation and wetness inside your bag. The advantage to the garbage bag is that you can get a bit of airflow from your feet up through your head, which minimizes condensation.

Given the choice between a garbage bag and a mylar space blanket, take the garbage bag.

The mylar blankets and bags may not be very good when used by themselves, but they do have some other wilderness survival applications. If you do choose to take one, spend just a few extra bucks and get one of good quality that's much sturdier. SOL makes some nice ones, called Heat Sheets. They cost just about $10 for a 2 pack.

Avoid trailhead theft with a “Climber’s Wallet”

Carrying your entire wallet and keychain on a backcountry trip is obviously unnecessary, but you also don't want to leave them inside your car at a sketchy trail head. Solution: the climber’s wallet.

Sadly, trailhead car break-ins happen from time to time. As you make plans to travel to remote areas, use some common sense when it comes to protecting your keys and cash. While leaving your wallet stashed in your car is not very smart, neither is lugging your entire keychain and wallet to high camp. Here’s a tip - minimize what you take on the climbing trip before you ever leave home.

Leave town with just a driver’s license, a credit card and maybe $40 in a ziplock bag. For keys, keep a house key and a car key on an additional key ring clipped to your larger key ring, so you can remove them easily for a climbing trip. Leave the other keys at home with the rest of your wallet.

(Tip: the amount of broken window glass on the ground at a trailhead is a good general indication of the safety of parking there.)

And, here's another preventative measure that some hikers have been known to use. Print out the following on a sheet or paper in large letters, and keep it on your dashboard when parked:

"Vehicle under video surveillance. Smile, so are you."

This will hopefully give anybody scoping your car a good reason to not mess with it. There are so many tiny and inexpensive video surveillance cameras out there these days, how do they know if you have one or not?

This is about all you need to carry when you leave the house for a hike or climb.

Keep your tent fly all the way under your tent to avoid a waterbed

This one might sound like a no brainer, but so many people do this wrong - Keep your ground cloth all the way underneath your tent.

If you put a ground cloth under your tent that's larger than the tent footprint, then all of the rain that runs off your tent fly is going to be funneled underneath your tent. Not good, unless you like sleeping on a water bed, and testing the quality of your tent floor.

To avoid this, just set up your ground cloth so the edge of the tent, or tent fly extends beyond the ground cloth. Tuck the ground cloth in underneath the floor of your tent an inch or so if you need to.

Dry out your tent after every trip

Don't you love that funky smell that old tents always seem to get after a few years? No, neither do we. Be sure and dry it out after your trip to keep it smelling fresh.

No matter how dry you think your tent is at the end of your trip, it’s always worth letting it hang for 24 hours in your house when you get home. Moisture can linger in strange corners of your tent, and it will soon create that unmistakable and hard to vanquish “moldy tent smell” if you don’t dry it out completely.

Never wash your tent in a washing machine, the agitator can damage it. Try handwashing with gentle soap in a bathtub, and air drying outside.

Read more detailed tent cleaning tips here.

This tip is from "1001 Climbing Tips" by Andy Kirkpatrick

Lose the Nalgene bottle

The long time standard for hiking water bottles is the one quart Nalgene. But, they are heavy and expensive and a bit over built for most hiking purposes. Here's a better option.

Wide mouth Nalgene bottles are pretty much the standard for many outdoor travelers. I get it, I have several.

Why are they popular?

Good places to put on some favorite stickers

Fairly indestructible

Good for car camping, trips close to the car where weight is not an issue

Pouring in hot water to warm up your sleeping bag on a cold night

They can go with you on every trip, and over time, can even become your inseparable little adventure buddy.

But, they have a few downsides, mainly cost and weight. An empty Nalgene bottle is 185 grams, and a new one will set you back about $10.

(Yes, Nalgene does make a so-called ultralight version, which reportedly weighs 106 grams for a 32 ounce bottle. That’s a big improvement, but those lightweight ones are hard to find; just about everyone seems to have the standard weight model.)

A better alternative? There are lots of options, but my favorite is the 20 ounce Gatorade bottle.

Essentially free; it's re-purposed from yourself or someone else.

Way more sturdy than most plastic bottles

Can hold hot water, which is helpful for drying out socks/gloves, and making a hot water bottle to put in your sleeping bag

Lightweight (only 36 grams)

Recycle it without a second thought if the microbes in your bottle get especially scary

Bottles like this are used by pretty much every every weight conscious long distance hiker

But wait, you say, I love my CamelBak! I must drink from a hose, so I can finish my hike FASTER!

Yes eagle-eye, I’m comparing a 20 ounce Gatorade bottle to a 32 ounce Nalgene. That's because the 20 ounce is my preferred smallish size. But the comparison math is easy. the Gatorade bottle is effectively 2/3 lighter.

Nalgene: 180 grams weight / 32 ounce capacity = 5.6 grams of bottle to carry 1 ounce water.

Gatorade: 35 grams weight / 20 ounce capacity = 1.8 grams of bottle to carry 1 ounce water.

I like to keep it in a lightweight mesh pocket on my shoulder strap; I got it from this store on Etsy. Search Etsy for “backpack and water bottle holder”. They come in several different sizes.

image: https://www.etsy.com/listing/944154329/

Need a big container for a really hot day or basecamp water storage? Check out the modern generation of water reservoirs. Here’s my favorite, the Hydrapak.

The equivalent three 1 quart Nalgene bottles are more than five times heavier than one Hydrapak! Cost is about the same as well. Downside, nowhere to put cool stickers. =^(

Note that this reservoir is only for water storage. It does not have a tube or a mouthpiece. There's probably some cool way to connect this to a lightweight water filter to make a gravity feed into another bottle. But that’s not my thing so I’ll let you figure out how to do that. :-)

Here's the Hydrapak in use.

It has a sturdy screwtop that’s connected to the bottle so you can't lose it

Two different handles, one on the top and one on the side

Convenient places to clip a carabiner so you can open the top and let it dry upside down