Alpine Tips

Avoiding burns in the backcountry

Fortunately there aren’t many ways you can suffer a burn in the backcountry. Here’s some easy ways to avoid it.

When pouring hot water into anything - cup, bowl, thermos, dehydrated meal - always put the receptacle onto a flat place, never hold it in your hand.

When you’re tending your stove, try to do it from a squatting position and not sitting. If you’re squatting, you can jump up and more quickly move away from spilled hot water or a flaring stove.

Lots of modern camp stoves might boil water in just a few minutes, but they are often tall and unstable. Try to secure your stove from tipping over by putting a few rocks around it to hold it in place.

Modern outdoor synthetic fabric such as fleece, polyester and capilene can be extremely sensitive to flame. As in, they can melt in a second or two, sometimes directly onto your skin, resulting in a serious burn. If you’re wearing these fabrics, be very careful around campfires and the intense flame of a camping stove.

Don’t step over a campfire or stove, step around it.

Also, sparks from a campfire can easily land unnoticed on your nice fleece jacket and instantly burn a small hole through it. Probably won’t hurt you very much, but it’s sure not helping your gear.

First aid for minor burns

Clean the affected area with cool water, not ice cold.

Cool the area by putting on fabric soaked with cold water. Don’t put ice or snow directly on the burn, this can cause frostbite and restrict circulation, which is needed for healing.

Moist dressings are fine for small burns (less than three percent of the body surface area). Use dry dressings on extensive burns.

Check every 24 hours.

Be cautious of “grade inflation” in climbing gyms

Don't let your head get big because you can climb “5.11” in the vanity gym. You may be in for a big surprise your first time outside.

Many outdoor climbing areas have a reputation for ratings that are relatively easier, or harder, than the generally accepted grade.

Red Rock Nevada? The bulletproof sandstone is sticky, the cracks eat cams, and the bolts are plentiful. You’ll probably feel like Superman and climb a grade or two above your normal level. (But, the climbs are long and committing and the rappels are prone to getting your rope snagged, so bring a headlamp!)

Joshua Tree California? Just about everybody seems to get spanked on their first day. Between the sharp rock that shreds your hands, and flaring cracks that don’t take gear very well, that “warm up” route can definitely feel like a lot harder!

Similarly, some indoor gyms have a reputation for “vanity grades”, meaning what they might call a 5.10 is really more like a 5.8 or maybe 5.9.

If this is the only place you climb, you may start to believe that your ability is higher than it really is. If you then head outside and try a route at this same rating, you may be in for a rude awakening.

To mitigate this: Climb at different gyms and get a sense of how the ratings vary on routes of the "same" grade.

On your first few trips outside, leave your ego in the car. Try routes that are a couple of number grades below what you think you can comfortably climb in the gym. Even if you can lead climb safely in a gym, try top roping a few pitches initially when you’re outside, and consider using a stick clip so you don’t deck before you clip the first bolt.

When making the transition from indoor to outdoor, it’s an important safety issue to have a realistic knowledge of your abilities.

Sure, you might feel like Superman in the "vanity gym", but wait till you try going outside.

How to sew with your Swiss Army knife

That sharp little pointy thing on your Swiss Army knife is good for more than you thought.

I don’t know about you, but I’ve carried Swiss Army knives around for decades, and always vaguely wondered if the awl was good for anything more than punching a hole through the occasional stout object. Turns out, it definitely is.

With a little practice and some stout thread (or even dental floss) you can turn your Swiss Army knife and a miniature sewing machine for backcountry repairs. Awls have been used for thousands of years to sew. You may find, as I did, that learning how to do it is surprisingly rewarding, and may leave you astonished once again at the cleverness of human beings.

As with many hands on skills, it’s a much better show than a tell.

Here’s a nice YouTube video that shows you how to do it.

Most common way to get lost in the Columbia River Gorge

People can get lost for any number of reasons, but there is one common factor in most “lost hiker” stories in the Columbia River Gorge. What do you think is the number one cause?

Quick, what situation do you think is responsible for more people getting lost in the Gorge than any other? (and the same probably holds true for many other parts of the world as well.)

Picture this scenario. It’s early April, you’ve felt stuck indoors after a long soggy Northwest winter, there’s a weekend forecast of clear sky, and you’re busting to get outside. You head out to the Gorge to try a tough trail that goes up approximately 3,000 feet to the plateaus of the Oregon side. You've hiked the trail a few years ago, but you don't quite remember where it goes.

No problem for the first 2,000 feet or so. The trail is obvious, and you’re feeling strong. But, as you continue to climb, snow patches appear, start getting thicker, and then your trail completely disappears under the snow.

Here’s your answer. Continuing on a trail that becomes covered with snow is the number one way people get lost in the Gorge.

If the trail you're on becomes snow-covered, it’s a great time to take a break and reassess your objective for the day.

How familiar are you with the rest of the trail?

Are you doing an up and back hike on the same route, or a loop that comes down a different way? (On an out and back, at least you can maybe retrace your footsteps.)

Do you have a solid GPS track on your phone GPS app or GPS receiver that you can follow, even if the trail becomes snow-covered?

The takeaway: When going on a hike where you anticipate snow at higher elevations, always be sure of your route, use a GPS track if you have it, and definitely consider turning around if the trail you were relying on is no longer visible.

(This tip was shared with me a while back from a Search and Rescue team member from Hood River. Now, I’m not sure if this is statistically accurate or not, as it only comes from this one source, but it is still a good cautionary tale.)

Glove tip - always bring 2 pair

Good rule of thumb for snow climbing: always bring two pairs of gloves at a minimum. They don't need to be name brand, especially your back up pair. Here's how to find some online.

While we all have wide range of cold tolerance for our hands, I consider at least two pairs of gloves for snow climbs mandatory. (Read the classic book “Annapurna” for some epic frostbite tales, if you need convincing.) If you ever drop a glove on a cold route and don’t have a spare (or at least an extra sock) you could be in serious trouble.

The gloves I bring on pretty much every trip are Showa Temres 282-02. They are inexpensive, waterproof, extremely warm, and work great. Here's a detailed article about these terrific gloves.

The second pair? Of course, the temperatures where you're climbing dictates your glove choices. In moderate conditions, a light windstopper or Powerstretch fleece may do the job.

For technical climbing in really cold conditions, many climbers bring three or four pairs of gloves.

The backups sure don't have to be name brand glove$ from the $pendy mountaineering $hop. Try an Amazon search for “cycling gloves”. Here’s a pair I got for road biking that do fine as a backup for climbing - stout fabric, windproof, and have touchscreen capable fingers. And, how can you go wrong for about $12?

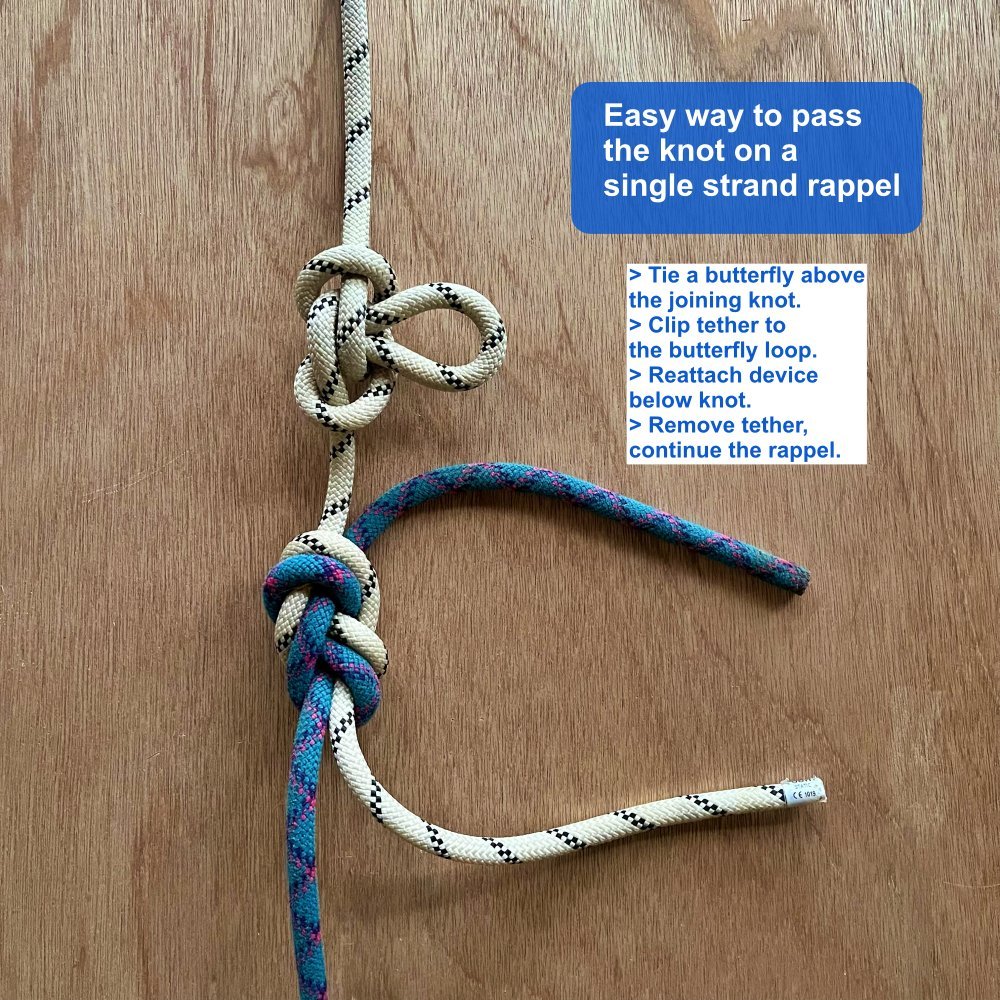

Easy way to pass the knot on a single rope rappel

It’s rare, but you might someday find yourself having to rappel two full rope lengths on a single strand. Here is a simple, fast and unconventional way to get past the knot.

This tip was written with the help of Bryan Hall, who is certified by the Society of Professional Rope Access Technicians (SPRAT) at their highest level.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

Short version:

You’re rapping on two ropes tied together in a single strand, and you need to pass the knot connecting the ropes to make it all the way down. (For some scenarios when you might need to do this, keep reading.)

Solution: Tie a butterfly knot just above the knot connecting your ropes. Use the butterfly loop as a ready-made clip in point when you’re passing the knot.

We're trying to keep it simple in this example, so we’ll assume you're on something less than completely vertical or free hanging terrain. On something less than vertical, you can momentarily “batman” down the rope to reattach your device as shown below, and hopefully also step up for a moment to unclip your tether.

If things are completely vertical, it gets a bit more complicated, more on that below.

What about passing the knot if you have a standard double rope rappel? Well, with some knowledge of Crafty Rope Tricks, you should pretty much never have to do this! Learn more at this article.

When might you need to rappel on two ropes tied together in a single strand?

You’re between one and two rope lengths up on a climb, and you have some sort of emergency situation: injured person, incoming lightning storm, impending darkness, whatever, and you just want to get to the ground ASAP and leave your ropes to get later.

You have two or more rope lengths below you on moderate terrain (4th class rock; steepish snow) that at least one person on your team is comfortable downclimbing without a rope. You send your whole team down on the two ropes tied together. The last person unties the rope, tosses it, and solo downclimbs. (or “downleads” by cleaning gear left by the next to last person. (Learn more about downleading here.)

You’ve fixed two or more rope lengths up to the high point on a big wall, and you’re rapping back down to the bottom. In a day or two, you’ll come back, ascend your ropes, and continue with the route.

You’re descending fixed ropes that someone else set up, like descending from Heart Ledge, Sickle Ledge or the East Ledges on El Capitan.

Anyway, those are some not-so-normal-but-entirely-plausible scenarios where you might need to pass the knot on a single rope. Can you think of any others?

Two ropes connected with a Flemish bend, with a butterfly loop in the “upper” rope so you can safely pass the knot. Try to tie this butterfly as close to the Flemish bend as you can.

The butterfly is one option; any bight knot will work. The Flemish bend is preferred for a single strand rappel over the flat overhand bend, which is a standard for rappelling on two strands.

1) Before you start down, girth hitch a clip a short (60 cm sling or PAS) tether to your harness, and clip it with a locking carabiner. Rappel down the upper rope, and stop when you get just above the butterfly.

2) Clip your pre-tied tether into the butterfly loop; remember to lock it. Nice, you're now secured to the upper rope with your tether.

3) Remove your rappel device from the upper rope. Yes, this will require you to get some kind of stance for your feet to unweight the rope a little bit. (If this steep or you're scared, you could tie a catastrophe knot in the bottom rope and clip it to your harness as a backup.)

4) Downclimb or “batman” down the rope until you're below the joining knot. Reattach the rappel device to the bottom rope.

5) Unclip your tether and continue with the rappel. Schweeet, you just passed the knot!

Typically, this is set up with just a knot connecting the two ropes, such as a rewoven figure 8 bend, also known as the Flemish bend, or simply a flat overhand bend.

Sure, these knots are safe enough, but it sure doesn’t give you any assistance when you need to get past the knot. This is the beauty of adding the butterfly loop - you have a ready-made, secure point to attach a short, repeat, SHORT, leash to add an instant safety when you’re transferring your belay device from the top rope to the bottom rope.

This process is MUCH easier if you can find a small stance for your feet so you can momentarily take your weight off your rappel device. This should typically be possible on steep snow, ice, or low fifth class rock.

If you’re trying to pass a knot on a completely free hanging rappel, things get more complicated. You typically would add a friction hitch or ascender above the knot, weight that, remove your rappel device and reattach it below the knot, unweight the friction hitch / ascender, remove it, and continue rappelling. If you find yourself having to do this in a very steep terrain, you’re probably a caver or big wall climber, have an ascender, aid ladder or other helpful gear, and have already practiced this technique. Even so, the butterfly knot can still give you a handy place to clip for additional security.

What about using a flat overhand bend on a single strand?

If you use a standard flat overhand bend here instead of the Flemish bend or a more robust knot, you're probably gonna be fine. However, it's not best practice for a single strand rappel. Here's a much longer article examining this issue.

Safety note: keep your rope tails about 30 cm

Typically, when tying two ropes together for a rappel, you tie the knot with long tails, at least one foot. Some folks do it closer to two feet (the extra length doesn’t make them any safer or stronger, but it might add a little psychological boost.)

However, anytime when tying two ropes together like this, you want to AVOID using very long tails. Reason: the person rappelling could make the fatal mistake of reattaching their belay device onto the tail(s), instead of the actual rope. Yes, it has happened. It probably sounds like a mistake you would never make if you’re reading this indoors on a nice sunny day, but if it’s at night, raining, in a cave, you’re physically and mentally fried, whatever, simple mistakes like this can happen all too easily.

Here's a longer article on this topic.

The better practice is:

Tie your knot to connect the ropes, and keep the tails about 30 cm / 12-16 inches max (or, about the length of your forearm.)

Tidy the knot properly, then snug it down (aka “dress it and stress it.”)

What's in my pack - alpine climbing by Steve House

It's a rare opportunity to hear from a world class expert on what specifically they bring for an overnight alpine climb. Get it straight from Steve House. (You’ll never believe what he fits in a 30 liter pack!)

Connect with Steve and learn cutting edge alpine training at his website, uphillathlete.com

Want to know what a world class alpinist takes for an overnight climb? Watch this great YouTube video as Steve House explains his detailed gear choices. You’ll be amazed at all of the gear he manages to fit in a 30 liter pack!

Some key points:

Food: pretty much energy bars

No Camelbacks or water bladders. Steve uses 600 ml soft flask collapsible water bottles. Carry no more than one liter total, because water is heavy. Put the flask in a mitten to insulate it if it's really cold, and try to always start off with hot water. He has a dilute electrolyte mix already in the water

When you get to your bivy, first thing to eat is some nuts (almonds cashews, raisins). Also, have some sort of recovery drink mix like Roctane. You want carbs, amino acids, and electrolytes in the recovery drink

Tries to avoid heating too much water, like for soup or tea, because that means you need to bring more fuel

Dinner: freeze dried food. 1 bag per person, 800 calories. Pour in boiling water, put it inside your jacket to stay warmer

Breakfast: instant coffee, 10 g protein powder, energy bar. Keep the energy bar in your sleeping bag so it's not frozen in the morning

Stove MSR Windburner. One small canister can last two people for one day, if you’re careful. Brings an extra foil windscreen for the stove. Generally does not use a hanging stove

Branched-chain amino acid tablets and electrolyte tablets to eat with dinner, for recovery

Gloves: up to four pairs of gloves! Take mittens, belay gloves, lightweight action gloves

Outer shell jacket: Patagonia Houdini if weather is good, Patagonia M10 if it’s going to be colder or windy

Patagonia hyper puff belay parka

Navigation: Garmin InReach, Garmin GPS, paper map in plastic bag, altimeter watch

Sleeping bag: one night trips always bring down bag, more than one night, almost always bring synthetic bag. (Exception, long expedition style climb like Denali when you’ll have the chance to dry out your down bag.)

Always keep a pair of dry socks stored in the sleeping bag. When you’re ready for bed, take off your damp/wet socks, put them on your chest to dry them, and put on the dry socks to sleep. In the morning, swap them, repeat for many days

Sleeping bag get stored inside the bivy sack, and not in a compression stuff sack

Neo air sleeping pad, folded up and put it inside the sleeve inside the pack; this can keep it from getting punctured

Take a 4‘ x 8‘ very lightweight nylon tarp, to string up over his bivy sack

Backpack: 30 Liter Patagonia Ascensionist

Put a trash compactor bag inside your entire backpack, and pack everything inside of that to keep it waterproof

DIY - Homemade chalk ball

Loose chalk, while a lot cheaper than a premade chalk ball, is also a big mess. But if you can get your hands on some delicate undergarments, you can easily make a homemade chalk ball on the cheap.

Tired of paying $5 plus for a chalk ball, when loose chalk costs about 1/3 of that? Here’s a way to make your own.

Take a woman’s nylon stocking/pantyhose. (Guys, how you procure this is up to you!) =^)

Cut off most of a leg

Put powdered chalk in the toe area. Do this outside, it makes a mess!

Tie an overhand knot in the leg. Instant chalk ball!

If the chalk comes out too fast, just invert the toe back into the stocking to make a double or triple layer of fabric.

How to make bomber tent anchors in snow

There's no such thing as a freestanding tent on a windy mountain. Here's a light weight and nearly free way to make solid snow anchors for your tent.

I was about 30 minutes outside of Camp Muir on Mt. Rainier, turning back after a storm-induced retreat. Just as I caught a view below me of the tent city, a giant gust of wind smashed into the camp, lifted several tents into the air, and cartwheeled them thousands of feet down the glacier and out of sight. Whoops! Fortunately, it wasn't mine, but lesson definitely learned!

If you’re setting up a tent in the snow, you need a good way to anchor it down. (There’s no such thing as a freestanding tent in a windy place.) Buried trekking poles, sticks (maybe collected on your approach hike), skis and rocks work well, as do some sort of a buried deadman. A picket is bomber, but you’ll probably need them for your climb.

Here’s a great choice: 1 gallon ziplock freezer bags. Reinforce the lower sides with duct tape, fill about 2/3 with snow, and seal. Then tie the tent cord around the middle making it into an hourglass-like shape, then bury it. For knots, use a tautline hitch or a trucker’s hitch to fine tune the tension on the tent cord. (See another tip of the week for how to tie these very useful knots!)

So, how strong are they? Answer, more than you think. A study by the French National Guide School conducted some pull testing on various types of deadman snow anchors, and they found that a buried plastic bag could hold a load of approximately 200 kg!

One more option: If you anticipate high winds but no precipitation, you can remove the some all of the tent poles when you leave camp, lie the tent flat, and put some rocks gently on top of it.

Don’t let this happen to you!

image: https://manonice.com/2014/10/

Tincture of benzoin - what it is, how to carry it

Tincture of benzoin is great to have in your first aid kit, as it's often the only way you can make tape stick to sweaty feet to prevent blisters. Here’s a crafty way to carry it that’s leakproof, low-cost, and very lightweight.

Tincture of Benzoin is a brown liquid that looks like iodine, which toughens skin and makes it very grippy for tape application.

Putting a dab on your heels be fore taping is a great way to get tape to stick on sweaty feet for blister prevention.

I always have it in my first aid kit. Put a few drops of benzoin on a fingertip, rub it over the area to be taped, and wait about 2 minutes for it to dry. Rip off some tape, and smooth it over the benzoined area. The benzoin will make the tape grip on your sweaty feet, and the surface of the tape provides a low friction surface to stop blisters from developing.

However, benzoin generally comes in a heavy glass bottle that holds much more than you’d need on a weekend trip.

It also comes prepackaged in some commercial first aid kits, in small glass vials or pre-applied on a Q-tip sort of thing. Both of these are Less Than Ideal, because the glass can break, and the single use Q-tip thing can dry out before you use it.

Here’s a great way to carry benzoin, with just the amount you need in a tiny container that will never leak.

Buy the tiniest (and cheapest!) bottle of eyedrops you can find – probably 1/8 of an ounce.

With a safety pin, slightly enlarge the dropper hole.

Squeeze out and discard the eyedrop solution.

Pour a bit of benzoin from the large drugstore bottle into a bottle cap or other small disposable container.

Squeeze the empty eyedropper bottle to make a vacuum, then place the tip into the bottle cap of benzoin.

Release, and the eyedropper bottle will partially fill with benzoin. Repeat until full.

Label the bottle. Cloth first aid tape and Sharpie pen works well.

Refill after a trip as needed. This weighs next to nothing, is leakproof, holds enough for many applications and it’s easily refillable. The original glass bottle is huge and holds more than you'll ever use, so feel free to share it with a friend.

Tiny eyedropper bottle about 1/2 full of benzoin, penny for scale.

Everyone carries a nut tool

You may think that a nut tool is only for the second who’s going to be cleaning the gear. Here's a few good reasons why the leader may want to carry one as well.

You may think a nut tool is only for the second, but it's a good idea if the leader carries one as well. Why?

If the leader yanks hard on a nut to set it, and then decides whoops, they want to take it out and use it somewhere else, they need a way to do that.

Sometimes the leader can use a cleaning tool to, ahem, “clean” placements that have dirt or tiny rocks.

If the second drops their cleaning tool, the leader has one as a backup.

Sometimes to try to extract a deeply buried cam, you may need two nut tools to pull on both sides of the trigger.

It's one of the least expensive and longest lasting pieces of gear you're ever going to buy, so pretty much every climber should carry one.

If you choose a bare-bones nut tool that does not come with its own racking carabiner, be sure and get a full strength mini carabiner for it, like the nice ones from Metolius. Don't use a cheap keychain carabiner for this, because someday you'll find yourself scavenging this carabiner for a real climbing purpose, and when that day comes you want to full strength one.

The Metolius Torque is a good choice. It has a carabiner built into clip to your harness, a smooth end to not hurt your palm so much when you smack it, and the clever design of several sizes of wrenches to tighten loose hanger bolts.

Tricams - part of the trad climber’s toolbox

If you have a close look at the harness of an experienced trad climber, odds are you’ll find a few tricams. There’s a reason for this. Learn why they may deserve a place on your rack.

Tricams are often an underappreciated bit of gear; if you haven’t used them, you might be missing out. Less expensive, lighter, and sometimes more versatile than active cams, they may well have a place on your rack. (This is especially true of the fabled pink tricam, which has a legendary following among a subspecies of trad climbers.) Once you get into harder grades you'll probably be reaching for spring loaded cams more often, but when you're learning and for easier terrain, tricams can be pretty sweet.

A few tricam tips . . .

Get the smaller sizes. A good starter set is the first four smallest units, least expensive when purchased as a set. You won’t have much use for the huge “cowbell” tricams, which are typically seen only on the harnesses of graybeard mountain goats, who have been climbing since Mt. St. Helens was a real mountain, and are still using harnesses braided from blackberry vines and mud.

Because they can be placed in so many positions, tricams can be great for building anchors. Consider using your active cams when leading, and keep tricams in reserve for anchor building.

In a horizontal crack, place the "stinger", or point, facing down. This usually gives a more secure placement. Tricams can be especially effective in horizontal cracks, because their flexible runner easily handles being loaded over the edge of the crack.

On lead, always try to extend the placement with a runner to minimize the rope wiggling the tricam out of position.

One of the main gripes against tricams is that they can be hard to clean, especially if the person that placing then gives a stout tug. This can be true! Don’t use them when you’re aid climbing and expect to ever get them back again, ask me how I know this.

Give a gentle tug to set them, but expect your second to curse a bit when they arrive and maybe even ask you for a take while they try to clean it. Be sure your second has a cleaning tool.

They now come in a few different flavors and different styles of webbing, but they all pretty much work the same way. And, as mentioned, consider the pink one at the very least!

https://www.backcountrygear.com/camp-dyneema-tricam-set.html

image: backcountry.com

Uses of the butterfly knot

The butterfly knot is probably something you didn’t learn on day one of climbing school. But after the basics, it's a good one to add to your toolbox. Learn four climbing situations where the butterfly knot comes in handy.

The butterfly is generally not one of the standard climbing knots beginners learn, but it’s well worth learning once you have mastered the basics.

It's often referred to as an “alpine” butterfly, but I have no idea why. Let’s drop the “alpine” and just call it a “butterfly” knot, okay?

Photo: butterfly knot used to isolate a damaged part of the rope.

How is the butterfly knot useful for climbers?

The butterfly is generally easier to untie after it’s been weighted. Use it anytime you're significantly weighting a rope (like fixing ropes for a big wall, or tying off one end of rope for snow anchor testing or crevasse rescue practice.) Grab each of the "wings" of the knot and flex them back and forth to untie. Once you gain some experience with the butterfly knot, you may find that you use it to replace the figure eight on a bight in just about every situation.

It’s symmetrical and can be loaded on either strand. This makes it a good choice for the middle member(s) on a rope team. While a figure eight or overhand on a bight is acceptable for the middle person, it’s designed to be weighted in only one direction. As the middle person on a rope team, you don't know which strand will hold you in a crevasse fall.

It’s adjustable. If, after you make the initial loop, you decide it needs to be a little longer or a little shorter, you can feed the slack through the knot to adjust the size of the loop. (You can do this with a figure 8 on a bight, but it's quite a bit more awkward.)

It can be tied as a “brake knot” between rope team members for glacier travel, to help minimize the length of a crevasse fall. Any kind of crevasse rescue situation is more difficult with just one person doing the pulling, but if you tie a few knots in the rope between you and your partner, these can hopefully catch on the lip of a crevasse in the event of a fall, and minimize the length of the fall. (Yes, they can complicate the rescue, but that’s another topic.) Under the right conditions, this has been tested and proven effective. There is also another knot that has a slightly larger diameter called the brake knot, which may be preferable for two person crevasse travel, but the butterfly is acceptable.

It can isolate a damaged part of the rope. Through stepping on the rope with a crampon, an ice tool puncture, being loaded over a sharp edge or maybe rock fall, a rope might get some minor damage so you’re not comfortable using it anymore. With the butterfly, you can isolate the damaged part of the rope inside a loop of the knot and you’re good to go, with a near full strength and full length rope. (Now you need to figure out how to pass the knot while you are on rappel or belaying . . . but that’s a different topic!)

How about a directional / in-line figure 8?

This might be a useful knot in some sorts of rigging situations, but for recreational climbing I personally don't see a need for it. Anything the directional figure 8 can do, the butterfly can also do, so why bother?

That's not just my opinion, Australian rigging expert Richard Delaney feels the same way, check out the short video below.

And, because it's pretty much impossible to explain how to tie a knot in words, here is a short and sweet video from REI that does the job.

(It's not my preferred method, because this darn knot has probably more ways to tie it than just about any other, but it works fine. My advice: just learn one good way to tie this knot and don't confuse yourself with several.)

Posting photos online? “Redline” your route

Posting photos of your latest mountain outing is great. How about making them a lot more useful by adding in some route info with simple drawing tools?

As we like to say here at AlpineSavvy: “A map or photo of the route is great, but a map or photo with your route drawn on it is better.”

You’ve just finished a climbing route that’s been on your tick list for a long time, you took a bunch of great photos, and you’re ready to post to social media.

If you have some good photos of the mountain and route, do everyone a big favor before you post: take a minute or so, use a simple photo editing tool, and “redline” your photo(s) showing exactly where you went. This turns your photo from a pretty picture into a useful tool for anyone who sees it. (And it sure doesn't have to be red, use any color you like.)

Drawing a simple line on a photograph can be done with lots of free or browser-based photo editing software. If you want to get fancy, you can add an arrow or some text annotation as well. (I’m a fan of PhotoScape X. It’s free, works on Mac and Windows, lots of features but still easy to use for simple things like text and arrows.)

Note that you don't even have to use your own photo for this. You can take a Google Earth screengrab, save it as a jpeg, and then draw over that. Examples are below.

It’s helpful to make a copy of the original photo before you start so you don’t mess with it.

Example: Here’s a photo of North Sister from the SW Ridge approach. Ho hum, pretty boring. But, add a simple line, and suddenly it's a LOT more useful. And, maybe add an arrow and annotation, which only takes another minute or so, to improve it even more.

Photo taken on route: North Sister OR, SW ridge. Yawn, not much help to anybody.

North Sister, SW ridge approach. Route redlined. Now we have something that’s actually helpful for someone else to routefind.

North Sister, SW ridge approach. Route redlined and key route beta added with arrow and text. (Gee, thanks for ruining my onsight!)

You can also do the same thing with Google Earth screengrabs. Here's an example of the Leuthold Couloir route on Mt. Hood.

Google Earth pro tip: You can easily save an image of your Google Earth screen from the menu. Try File > Save > Save Image. It even lets you add a title and description to your saved image, as you can see below.

Mt Hood, Leuthold Couloir route, Google Earth screen grab.

Mt Hood, Leuthold Couloir route, Google Earth screen grab, with route redlined.

Mt Hood, Leuthold Couloir route, Google Earth screen grab. Route redlined, and adjacent "off route" areas shown.

One other good way to use Google Earth screen grabs is to have your route drawn in with a KML file, and then zoom in close to the ground and take screen grabs looking up the route. This gives you sort of a virtual “climber’s eye” view that can be really helpful for route funding in the field.

If you want to learn how to use KML files in Google Earth, check out this video.

Here’s an example of the Fisher Chimneys route on Mt. Shuksan in Washington, on a section with notorious route finding difficulties. Zoomed close to the ground like this can give you a good reference for making better real world route choices.

Bring some earplugs

Want to get a good night’s sleep on your next alpine climb? Bring some earplugs.

Getting a good (well, at least passable) night’s sleep can be a big factor in your climbing success. A tent flapping in the wind or a snoring tentmate can be easily thwarted with the humble earplug.

Tip – buy a pair that’s connected with a foot or so of string. When one falls out (and it will) it can be easily retrieved and won’t be lost in the folds of your sleeping bag.

Carry them in small plastic bag so the string doesn’t get too tangled up. Get the plugs at a good hardware store or online . They do get lost, even with the string, so get a few pairs when you’re shopping.

DIY - heavy tinfoil - ultralight, foldable pot lid

Tinfoil - a free, foldable and ultralight way to make a lid for your pot.

Use a square of heavy weight aluminum foil for a pot lid. Packs well, and it’s super light. Put a pebble on the top to keep it in place.

Or, try a circle cut from a disposable pie tin. Crimp the edges down around the top of your pot.

Lose the Nalgene bottle

The long time standard for hiking water bottles is the one quart Nalgene. But, they are heavy and expensive and a bit over built for most hiking purposes. Here's a better option.

Wide mouth Nalgene bottles are pretty much the standard for many outdoor travelers. I get it, I have several.

Why are they popular?

Good places to put on some favorite stickers

Fairly indestructible

Good for car camping, trips close to the car where weight is not an issue

Pouring in hot water to warm up your sleeping bag on a cold night

They can go with you on every trip, and over time, can even become your inseparable little adventure buddy.

But, they have a few downsides, mainly cost and weight. An empty Nalgene bottle is 185 grams, and a new one will set you back about $10.

(Yes, Nalgene does make a so-called ultralight version, which reportedly weighs 106 grams for a 32 ounce bottle. That’s a big improvement, but those lightweight ones are hard to find; just about everyone seems to have the standard weight model.)

A better alternative? There are lots of options, but my favorite is the 20 ounce Gatorade bottle.

Essentially free; it's re-purposed from yourself or someone else.

Way more sturdy than most plastic bottles

Can hold hot water, which is helpful for drying out socks/gloves, and making a hot water bottle to put in your sleeping bag

Lightweight (only 36 grams)

Recycle it without a second thought if the microbes in your bottle get especially scary

Bottles like this are used by pretty much every every weight conscious long distance hiker

But wait, you say, I love my CamelBak! I must drink from a hose, so I can finish my hike FASTER!

Yes eagle-eye, I’m comparing a 20 ounce Gatorade bottle to a 32 ounce Nalgene. That's because the 20 ounce is my preferred smallish size. But the comparison math is easy. the Gatorade bottle is effectively 2/3 lighter.

Nalgene: 180 grams weight / 32 ounce capacity = 5.6 grams of bottle to carry 1 ounce water.

Gatorade: 35 grams weight / 20 ounce capacity = 1.8 grams of bottle to carry 1 ounce water.

I like to keep it in a lightweight mesh pocket on my shoulder strap; I got it from this store on Etsy. Search Etsy for “backpack and water bottle holder”. They come in several different sizes.

image: https://www.etsy.com/listing/944154329/

Need a big container for a really hot day or basecamp water storage? Check out the modern generation of water reservoirs. Here’s my favorite, the Hydrapak.

The equivalent three 1 quart Nalgene bottles are more than five times heavier than one Hydrapak! Cost is about the same as well. Downside, nowhere to put cool stickers. =^(

Note that this reservoir is only for water storage. It does not have a tube or a mouthpiece. There's probably some cool way to connect this to a lightweight water filter to make a gravity feed into another bottle. But that’s not my thing so I’ll let you figure out how to do that. :-)

Here's the Hydrapak in use.

It has a sturdy screwtop that’s connected to the bottle so you can't lose it

Two different handles, one on the top and one on the side

Convenient places to clip a carabiner so you can open the top and let it dry upside down

Using gear tethers for items outside your haul bag

On a big wall, not everything is going to fit into your haul bag. No worries! Use gear tethers to hang your extra stuff outside of your bag and keep it accessible.

image: from the outstanding book “higher education” by Andy Kirkpatrick, used with permission

Not everything is going to fit in your haul bag. And, there are some things you don't want to put in there! Typically, these items might be your portaledge, poop tube, gear bag, garbage sack, empty water bottles, day bag and maybe a gear bucket.

The Old School technique for dealing with extra items like this was to clip them underneath your haul bag. Even if you've never climbed a big wall, you can probably imagine what type of problems this creates. Every time you’d need to access your extra items, you'd have to finagle yourself underneath your haul bag, a major and unnecessary hassle.

Fortunately, there’s a Superior System - gear tethers. Rather than clipping your gear under the bag, you tie it with the tether attached to the top. This allows you to grab the gear tether, and simply pull up whatever you need.

A tether is simply a length of cord about 5 meters long. Typically the cord is 8 mm. (If you're attaching something heavy, 10 mm is a little easier on your tired wall hands.)

Tie a figure 8 on a bight in the middle and clip it with a locking carabiner to your main hauling carabiner. This gives you two tethers about 2.5 meters long each.

Get another 5 meters section of cord of a different color, and do the same thing. The color coding helps you remember which rope to pull.

And, as long as you’re buying 8 mm cord, you might as well get yourself another 15 feet to use as a docking tether for the actual haul bag, which we cover in this Tip. (Ideally the docking cord is a different color from the cords you use for gear tethers, to be sure you don’t accidently release the wrong one.)

Be sure the cords are long enough so whatever is attached to them hangs below your haul bag, otherwise it gets pinched between the bag and the rock.

Important: everything on a gear tether has to be on a locking carabiner. (Use a ”cheapskate locker” if you need to, a regular carabiner taped shut.)

Here's a fancy way to set it up, from big wall expert Skot’s Wall Gear.

Here, Skot is using a pair of rappel rings (gold) along with a combination swivel and locking carabiner (appears to be the Director Swivel Boss from DMM). This makes a more compact set up, with zero chance cross loading the rings.

Note that each bag has one docking cord, and at least two gear tethers.

An excellent use of gear tethers. Image: Mark Hudon

image: https://hudonpanos.com/Wall-Tips/All-Things-Haul-Bag.pdf

Double portaledge, or two singles?

Buying a portaledge is $$$! You want to be sure and make the right choice. What are the pros and cons to a single versus a double ledge?

A portaledge is probably the single most expensive item of gear or you'll ever buy for climbing. So, you want to be sure you get the right one for you. Double or single? There are arguments for both approaches, but consider:

Double portaledge benefits

a double weighs a lot less then two singles - maybe not a big deal when you are hauling, but you'll definitely notice it on the hike out. (Metolius Bomb Shelter example: about 11 lbs. for a single compared to about 13 lbs. for a double)

a double is less $$$ than two singles

a double usually is faster to set up then two singles

a double can be easier to set up at a cramped bivy; while two singles often requires some crafty placement, with one of them sometimes in a Less Than Ideal (LTI) position or off of a marginal anchor, or both

Even for the solo climber, a double offers you more room inside to put your gear, lounge on, and hunker down in in the event of a storm.

(Downside in a storm: the doubles can become a larger sail, potentially tossing you around.)

Why might you choose a single portaledge?

If you are fairly small, a single is easier to set up, or you're fairly tall, giving you room to sleep diagonally.

Singles typically get more “square footage of bed space” per person

If you know you have stinky feet or snore a lot or have some, show we say, intestinal issues, having a little distance and privacy and your partner might be a good thing. Ergo, single.

Recommended double portaledge: Metolius Bomb Shelter or John Middendorf's D4 ledge, available at bigwallgear.com

image: www.metoliusclimbing.com

image: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1188459201/the-d4-portaledge

The Flemish bend for connecting two rope ends

The flat overhand knot (formerly known as the European Death Knot, or EDK) is a fine choice for general rappelling. But, if you’re rapping with an extra heavy load, toproping with 2 ropes, or just want a little extra confidence, here’s an excellent, easy-to-tie alternative.

The flat overhand bend (known for a long time with the now out-of-favor, tongue-in-cheek name of the "EDK", or "European Death Knot"), is a solid choice for tying together two rappel ropes.

Why is the flat overhand bend popular?

Quick and easy to tie

Easy to check if you tied it correctly

Strong enough, to do the job

As an “offset” knot, it tends to rotate and ride up over potential obstacles, like rock ledges, where many other knots might get hung up

But, let’s face it. Some people think it just looks sketchy. (How do you think it got that great nickname?) Doubters don’t care that 789,000+ happy rappels have been done on this knot with no issues; to them, it just doesn't look that stout. This can be especially true if you are tying it in Less Than Ideal (LTI) circumstances such as:

With two ropes of very different diameters, such as a 10 mm lead rope and a 6 mm tag line that you're using only to make double rope raps

With extra heavy loads, such as in a rescue situation, tandem rappel, or with a haulbag / heavy pack

Maybe when it's wet, dark, cold, or all of the above, and you just need a little extra mental boost to be SURE your rap knot is bomber

Or, maybe you have a scenario with a single strand, such as:

Big wall climbing, where it's common to have multiple single strands together so you can go up to a previous high point, or descend back to your bivy

Canyoning, where it’s common to rappel on a single strand

Rescue/retreat situation, when you tie two ropes together to descend a long way as quickly as possible, leaving the ropes in place to hopefully get later or be tossed by another team

Rappel situation down terrain where at least one person on the team can safely downclimb. Tie ropes together for all other team members to rappel, last person tosses the rope and climbs down unprotected

A knot that takes just a few extra seconds to tie, that uses a foundation figure 8 knot that every climber already knows, unties easily after loading, and can be a lot more confidence inspiring is called the Flemish bend, or a rewoven figure 8 bend.

(Knot geek terminology detour: a "bend" is the term for a knot that attaches the ends of two ropes together.)

This knot is fast to tie, works bomber with ropes of two different diameters, is easy to check if you’ve done it correctly because all climbers are familiar with a rewoven figure 8, can inspire confidence when doing a sketchy rappel, and super strong, even on one strand. And who doesn’t want a little more that sometimes?

Considering using the Flemish bend if you have a very clean pull for your rappel, without many obstacles. If your rappel is blocky and has potential places where the rope could get hung up, it's probably better to go with a flat overhand bend (or maybe a “stacked overhand”, which is simple 2 overhand bends tied next to each other) to minimize the chances of the rope getting caught.

Another perfectly fine option is the classic double fisherman's knot. I prefer the Flemish bend because it's faster and simpler to tie, easier to inspect, and easier to untie after loading.

Important note: The Flemish bend is completely different than the flat figure 8 bend, which looks similar but has both ends of the tail coming out the SAME SIDE of the knot.

The Flemish Bend has the rope tails coming out of OPPOSITE SIDES of the knot.

In most parts of the world, it's considered best practice to not use the figure 8 bend. The knot can roll when loaded, has caused fatal accidents.

Apparently it is quite popular in the French alps, for reasons the rest of the world does not understand yet.

Here’s a study, from Tom Moyer, that shows the relatively low loads in which the figure 8 bend can fail.

So, let's learn how to tie it correctly.

Here's a nice video showing how. (The overhand backup knots are optional, I didn’t use them below.)

Step by step instructions:

1 - Tie a figure 8 knot near the end of one of your ropes, with about a 1 foot of tail - no longer.

2 - With the end of your other rope, start retracing the figure 8 knot.

3 - Continue retracing . . .

4 - Complete the retrace, and check for about a 1 foot of tail. If you're a little short, you can push through a bit of rope to adjust the length.

Important: the ends of the ropes should be pointing in OPPOSITE directions when you're done if you've tied it correctly.

5 - “Dress it and stress it”. Remove any twists and pull the slack out of all four strands, just like you would for a rewoven figure 8 tie-in knot. There we go, all snugged down and ready to rappel.