Alpine Tips

The “25 foot” notice

When the leader approaches the anchor, giving notice to your belayer can expedite the climb.

This tip is from big wall expert Mark Hudon. See more great tips and El Cap route photos at his website, hudonpanos.com

When the leader gets close to the anchor, they yell down to the belayer, “25 feet” and an estimate of the time it might take to get there. This signals the belayer to wake up from their nap (napping, one of the joys of big wall belaying with a Grigri), start breaking down the anchor, make sure the haul bag is ready to be released, get ready to clean, etc.

4 reasons not to simul-rappel

Simul-rappelling has more than a few downsides, both in terms of speed and safety. If you choose to use it, be aware of the potential problems and be sure to practice in a controlled environment.

Simul-rappelling is a technique in which two climbers rappel a single strand of the rope at the same time, counterweighting each other. While this is typically thought of as an advanced maneuver that you should only try when you really have to, such as an incoming lightning storm or on a very long multi pitch route, in some climbing circles it's being used as a more standard way to descend.

As you will discover below, I'm not much of a fan. However, there are a couple of situations when a simul-rappell might be a good idea.

If you need to rappel down some gully with loads of loose rock, a simul rap might be a good idea, because rocks that you kick down when you’re side-by-side won't nail anybody below. But, hopefully you don’t find yourself in a situation like this very often, as a standard rappel route should rarely be in dangerous areas like this.

Teaching a beginner to rappel - the more experienced person can descend right next to the beginner, and perhaps even be clipped to them loosely, to offer advice and encouragement.

image: http://theconspiracytimes.blogspot.com

If you and your partner are both solidly experienced with the technique, and observe a few common sense precautions such as:

knots in the end of the rope

using a third hand autoblock backup below your rappel device

being sure both strands of the rope reach the next rappel station

and possibly tethering yourselves together with a long sling

then simul-rapping it can be reasonably safe and possibly save you a little time.

But think about it: by the time you've added the knots in the end of the rope, the auto block back up, and tethering yourselves together with a sling, could you have already been down rappelling the normal way?

Or, as some people have described it, “being fast isn't particularly safe, and being safe is not particularly fast.”

Side note: If you want to improve your speed AND safety when rappelling, try pre-rigging your rappel on an extended sling. Both climbers rig at once, so they can check each other, and then the second can begin heading down the moment the first person is off rappel at the next anchor.

(One other tip, mentioned to me by a canyoneering expert: If you have to simul rappel with someone who is a relative beginner, you can put a carabiner block on their side of the anchor. That way, if they screw up and tension goes off the rope on their side, the block will catch in the anchor and you will not fall.)

However, there are some major downsides to simul-rappelling, both in terms of safety and speed.

IFMGA Certified Guide Rob Coppolillo, co-author of “The Mountain Guide Manual”, wrote the following article in Climbing magazine which summarizes the shortcomings. Below is a direct copy/paste, in italics.

(Note, not mentioned by Rob is the hopefully obvious downside of doubling the load on the rappel anchor. If it’s bolts, probably not an issue. If it's anything slightly sketchy, then potentially a big issue.)

Simul-rappelling without both climbers having a backup (third-hand) on their respective brake strands doubles the chances of a catastrophe. Should one climber lose control, the rope will feed through his rappel device and begin sliding through the anchor.

If one climber unweights his rappel, it introduces slack into the system and the rope will slip at the anchor, effectively dropping the other climber. If this occurs at an unlucky moment, or the rope begins to pull unchecked through the first climber’s device, it can result in a tragedy.

Less-experienced climbers typically rappel slower on a single-strand of rope because the relatively low friction of a single-strand rappel makes them nervous. They elect to simul-rappel, but then fail to make up any time because of the slower rappel.

While simul-rappelling, both climbers arrive at the next rappel station nearly simultaneously, which can be awkward (and slow). Typically, one rappeller waits up top while the other manages the anchor and/or transition. Having one climber prep the station speeds up the second climber going off rappel. Often it would be faster (and safer) to simply rappel in a traditional fashion.

Finally, if you want a few more good reasons not to do it, here's a quote from Canadian expert climber Will Gadd’s personal website:

“Don’t simul-rap and otherwise get tricky on your raps until you’ve really, really figured your systems out, and even then simul-rapping doesn’t generally speed things up much. If you are going to simul rap then have knots in the ends of the ropes, have some sort of prussic attaching the one climber to the other’s rope (so if one person loses control both don’t plummet, and if this idea doesn’t make sense then definitely don’t simul-rap), consider putting a blocking knot on the weak climber’s side (with a quick link so it doesn’t pull through), use auto-blocks on each climber, etc. I did a lot of simul-rapping over the years but have pretty much given up on it in the last decade, it’s open to problems unless so many control measures are put in that it becomes very slow. Very, very rarely is simul-rapping justified by expediency . . .”

Three ways to improvise an arm sling

Using a triangular bandage for an arm sling is way old school. Learn three simple ways to use a coat and an extra T-shirt for a makeshift sling.

I saw a version of this in a recent wilderness first aid class that involved cutting up your shirt with scissors or a knife. It looked slick, but was pretty hard on the shirt! Here are three simple (and easier to remember) methods that don’t require you to cut up your gear.

Note - After you make one of these improvised swings, it's a fine idea to further secure that arm to your body so it doesn't flop around. Several ways to do this are an ace bandage, tape all around your torso, or a couple of heavy duty safety pins.

Method 1 - Elbow in coat hood

If you have a coat with a hood, insert the elbow of the injured arm into the hood, then tie the sleeves snug on your opposite shoulder.

Method 2 - Elbow in coat sleeve

If you have a coat, insert the elbow of the injured arm into the sleeve of your coat, which will bend your elbow and put your hand somewhere on your upper chest. Zip up the coat (probably with the help of a friend) and your arm is secure.

(Bonus points to freak out your friend: Put your right hand inside your jacket, put your right sleeve in your pocket, and use your right hand some creative way - Pretend to have an actively beating “heart”, make it crawl out from the top of your shirt and start going around your neck, etc. Try it in a mirror, it looks amazing. :-)

Method 3 - Extra shirt “necklace”

If you only have one shirt, this works, but if you want your chest to stay covered, you’ll need a second shirt.

Take your extra shirt, put your head all the way through it, and leave it around your neck like a necklace.

Let's assume your right arm is injured. Reach your right arm underneath the sling shirt, insert your hand down the left sleeve, tuck your right elbow into the right sleeve. Finally, tuck the extra fabric around your right elbow.

Knotting the ends of your rappel rope - three approaches

Most climbers agree that putting some sort of knot in the end of your rappel rope is good insurance for not zinging off the end of it. But, there are several ways to approach this, with pros and cons to each.

It’s generally accepted as Best Practice to put a knot(s) in the ends of your rappel rope, to prevent the catastrophic accident of rapping off the ends. (This is also known as making a ”closed system”.)

Of course, if you’re rapping off a single pitch route and you can CLEARLY see that both ends of the rope are on the ground, a knot in the rope ends is not necessary. However, especially if you’re more of a beginning climber, it can be important to build good technique by repeating the same Best Practice all the time, so no one should chap on you if you decide to tie a knot in both ends of the rope.

There are a few different ways to approach this, and as with most aspects of climbing, no single one is right or wrong. Let’s explore each method and look at a few pros and cons.

Method 1 - Stopper knot in each strand

Method 2 - Tie both ends together

Method 3 - Clip both ends to your harness

Method 1 - Stopper knot in each strand

This is probably the most common technique. One benefit to this is that any twists generated by rappelling can work themselves out.

However, there are two reasons why you might not want to do this.

1 - A fairly common scenario that can lead to a Major Rappel Epic is forgetting to untie one or both knots in the rope before you start to pull the rope, and realizing, only too late, that you have a knot above you that will not pass through the rap anchor above.

F#$%^&*K!! Big Problem!!

(This usually happens when climbing with a new partner, when one of you likes to tie knots in the end of your rappel ropes, and the other one for some reason does not, and that other person decides to pull the rope without checking. Ask me how I know this . . . )

Do you or your partner REALLY want to put a prusik knot on that rope and ascend 60 meters, hoping like hell that stopper knot is somehow securely jammed in your anchor? The answer is NO, you definitely do not!

If you climb long enough, this will very likely happen to you, and hopefully you realize it FAST, when that damn knot is dangling only a couple of feet above your head, and you can do some crafty trick to pull it back down to you.

There are some ways to lower the chance of this happening.

If your rappel ends on the ground, make it the task of the first person down to untie both of the knots. You don't need them anymore.

If you have a multi pitch rappel, have the first person down use the “J loop” system: tie a figure 8 on a bight in both strands and clip it to the anchor. Now, the stopper nuts or no longer needed. The first person down can untie both of them, thread the pull strand threw the anchor, and tie one stopper knot in the new pull strand.

Develop the habit of maintaining control of the strand that's going up until the last possible moment when it gets pulled out of your hands. If you're sloppy with this and let loose and swing out away from you on an overhang or blow away from you if it's windy, you might find that knot is out of your reach even if you haven't started pulling yet. You don't have to hold it in your hands, you could simply clip it through a quick draw attached to either you or the anchor.

Very unlikely but very serious: You may tie a knot in one rope strand and forget to tie a knot in the other. If this were to happen, and the person rapping slides to the end of the rope, not only do they fall to the ground, they also could potentially pull the rope all the way through the anchor above, leaving your partner stranded. Depending on how remote your climb is, this could be an extremely serious situation.

Super important - ALWAYS be sure the knots in your rope are untied before you pull your rappel!

Note on stacked rappels and ONE stopper knot: This may well be the best solution of all for multi pitch rappelling: Both partners (or at least the second) use an extended rappel and pre-rig with an autoblock backup. Having the second person with their rappel device already on the rope and an autoblock fixes both strands of rope for the first person down, and the rope therefore can never slide through the anchor.

This means that you only need to tie a stopper knot in ONE strand of the rope. If the first person down were to rappel into the stopper knot for any reason, it can’t pull through the anchor because it's locked in place by the person above them. This also means that on multi pitch rappels, the first person down can thread the pull strand of the rope through the lower anchor, tie a stopper knot in it, and then pull the rope, which will pass through the upper anchor, and fall down past the lower anchor. No need to pull that strand back up to tie a second knot, a big time saver!

Method 2 - Tie both ends together

The solution to both of these problems is to tie both ends of the rope together. An flat overhand bend with about 1 foot of tail works fine.

This definitely eliminates problem number one, starting to pull the rope with a knot still in the end. If you start to pull the rope with both ends tied together, you have a closed loop, so you can easily retrieve it, untie the knot, and then continue pulling.

It also eliminates scenario number two, unlikely as it may be, because anyone who falls to the end of the rope is going to hit that knot and (probably) stop.

Many climbers dismiss this method because they think that twists in the road generated by rappelling have no way to work themselves out of the ends. The amount of rope twisting can vary a lot depending on the diameter and stiffness of your rope, your rappel device, etc., so experiment with this in a controlled environment and see how it works before you adopt it as a regular system.

Method 3 - Clip both ends to your harness

(advocated by Andy Kirkpatrick. See his great book, “1001 Climbing Tips, #252 for more.)

How about taking both ends of the rope and tying each one separately to your belay loop? This solves both the problem of rapping off the end of the rope and problem of pulling the rope before you untie the knot. If you get some twisting near the bottom, simply unclip the knots and continue down.

One clever modification to this, suggested by Andy: when attaching the rope ends, tie a figure 8 knot for the pull rope and an overhand knot for the other, to remind you which rope you're supposed to pull.

This gives an additional benefit: the rope is less likely to snag, because the rope is hanging in a loop below the rappeller. With this method you you don't even need to throw the ropes. This makes it a good idea if there are climbers below you, it’s windy, you have a low angle rappel, or terrain with lots of shrubs, blocks etc. for the rope to hang up. Flake out the ropes carefully on your ledge, lower a bight of rope, the rappeller starts down, and the partner feeds out remaining rope as needed.

An additional benefit to this method is because you only have at most 30 meters of rope hanging below you, (assuming you're using a 60 meter rope) you're reducing the risk of damaging your rope if you knock off any rocks.

This technique can become more important in blocky terrain, high winds, low visibility, or if you're not sure where the next anchor is. Or some epic combination of these - basically, all the rappel situations that are Less Than Ideal.

Add clip in tethers to your wall rack

Your gear rack is arguably the most important, and certainly most expensive, thing you have on a big wall. You absolutely, positively, never want to drop it. Here's a quick harness modification to be sure It always stays where it should.

Rule #1 of big wall climbing: everything has a clip in point.

There are a lot of critical items on the big wall climb, but probably the most important (and expensive!) one is your gear rack. You absolutely never want to drop it! Here's a way to minimize the chance of that ever happening.

Get two strands of stout cord, each one about arm’s length. (I’m kind of a cheapskate, so I use parachute cord; it’s rated to about 550 lbs. and plenty strong enough. 5mm cord would also be a good choice, and a bit more durable.)

In one end of the cord, tie a bowline around each shoulder strap of your gear rack so the cord is permanently attached. In the other end, tie a small figure 8 on a bight loop, just small enough to clip a carabiner. Repeat for the other cord and other shoulder strap.

When you finish your lead and are at the anchor, pull the two cords around to the front, and clip each one to a separate anchor component. Only then, after the rack is secured to the anchor by these two redundant points of connection, do you take it off your body.

By clipping to two parts of the anchor you spread it apart a little bit, giving easier access to restock the gear when your second arrives after cleaning the pitch.

This tip is from big wall experts Pete Zabrok and Mark Hudon

DIY - Homemade alcohol stove

You could spend $200+ on a high tech canister stove . . . or make one from a a cat food can in a few minutes. Unless you're melting a lot of snow for water, you really don't need to boil water in three minutes.

It's easy to be seduced by the sexy merchandising at your big outdoor store, especially the dizzying array of high-tech stoves. (Yes, I‘ve used it, and it’s an amazing snow melting inferno, but $240 for an MSR Reactor stove, seriously?!)

But, if you're tempted to get one of these, ask yourself this simple question. When I’m on a fair weather backpacking trip or climb, do I REALLY need to boil water in three minutes, or can I wait a few more? You know the answer. You can probably wait.

So, try this. How 'bouta stove:

that costs about $0.50 in parts

you can make in about 10 minutes with simple household tools (or even a Swiss Army Knife)

burns cheap, readily available fuel

burns silently

weighs under 1 ounce

has no moving parts that can break

boils a pint of water in about 8 minutes?

Check out the link at the button below.

Homemade alcohol stoves are big with long distance hikers, and have been solidly field tested. One popular model is called a "cat" stove, simply because it’s often made with an empty cat food can.

I've made a few of these stoves and they works great. It’s not designed to melt snow on an expedition, but for a shorter trip in mild weather it could easily serve as your main backpacking stove. If nothing else, it’s a fun evening project, good for scouts, and could well serve as a disaster preparedness item - with some rubbing alcohol and a few cat food cans, you can cook food after The Big Earthquake when gas and power may be down. A windscreen made from heavy duty tinfoil and a paperclip is a fine addition.

Here's a shot of my cat stove in action. Just a cat food can with two rows of holes.

(Note, the soot on the pan is not from the stove, it's from cooking over a real fire)

A great rappel check acronym - BRAKES

Having a standard system to check your rappelling set up before you head down the rock is a fine idea, especially for beginners. Here's an acronym to check all the relevant components.

Rarely does Alpinsavvy post material directly from another website. But in this case I will, because it’s pretty darn good.

A similar rappel check acronym I’ve used is BARK (Buckle, Anchor, Rap device, Knot) but I was never quite satisfied with that one, because it left out securing the ends of the rope, and putting in an auto block. This new acronym nicely covers both of those.

The below content is straight from Climbing magazine

BRAKES - a system check for rappelling

Prior to rappelling, you should check every aspect of your system. The rappelling safety acronym BRAKES, developed by Cyril Shokoples in 2005 and now widely used by climbing schools, can easily be employed as a pre-rappel checklist. It’s a good idea to go through this list out loud by stating each letter and touching the part of the system you’re checking. Confirm with your partner when possible that each component of the system has been set up appropriately and is going to be applied correctly.

B – Buckles: Check the buckles on your harness. Make sure they are snug and that all appropriate straps are doubled-back.

R – Rappel Device/Ropes: Check that the carabiner attached to your device is locked, both strands of the rope have been loaded correctly in the device, and the rope is properly threaded through the rappel anchor.

A – Anchor: Confirm that the anchor is strong. If it’s a tree, make sure it’s alive, large enough to hold your weight, and that it has a good root base. If it’s a boulder, ensure that it is not going to move. If rappelling off bolts or gear, confirm that they are suitably strong enough. Double-check that any webbing or cord isn’t damaged or too faded.

K – Knots: Check all the knots in the system. Make sure that knots adjoining two ropes in a double-rope rappel are correctly tied with enough tail.

E – Ends: Confirm that the ends of your ropes are on the ground or that they reach the next anchor. Confirm that your system is closed with knots at the end of your rappel lines.

S – Safety Backup/Sharp Edges: Use an autoblock backup and check to make sure that you aren’t going to rappel over any sharp edges.

The auto locking Munter hitch

While more of a trick knot used by guides, the auto locking Munter hitch can still be a good tool in your bag of Crafty Rope Tricks (CRT).

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

An old school yet effective way to belay your second is with a simple Munter hitch. The Munter has one advantage over an auto locking belay device such as a Black Diamond ATC or Petzl Reverso, in that you can easily lower your second if you need to. However, most people think that one of the downsides is that the Munter does not have the nifty auto lock feature that these belay devices offer.

Not so, grasshopper! With this crafty rope trick (CRT) you simply add one carabiner to a Munter hitch to make it autolocking. There are a couple of ways to do this.

Here’s one method. By adding the carabiner, the hitch remains in raising mode, and can't “flip” into lowering mode.

A few things to note:

Let’s start off by saying this is kind of a guide trick, and may not have a lot of utility for recreational climbers.

This knot is best used in situations where the chances of the second needing to be lowered is unlikely. This is a subjective choice that depends entirely on the skill of the climbing team. Also, it should probably not be used on any sort of traverse where you might swing into something vertical or overhanging. If there’s more than a slight chance that the second may need to be lowered, it’s probably better to use a regular Munter hitch or some other belay method.

Let’s start with a few general principles of Munter hitch belay.

As always when using a Munter hitch, it’s best to use a large pear-shaped “HMS” belay carabiner with round metal, which helps minimize friction.

Using a thinner rope or a new one with a sheath that’s a bit slippery works best. I’ve tried it with my ancient 10 mm workhorse rope with a fuzzed up sheath, and it’s quite a bit of work to feed that rope through the hitch.

You want to use two hands. Your”feed” hand pulls in slack rope and the the brake hand simultaneously pulls it down. If you only pull on the brake side of the rope, you’re going to get a lot more friction, do more work than you need to, and potentially get some twists into the rope.

Some specifics of using this hitch in auto lock mode:

You can add or remove this auto lock method into the Munter belay at any point in the pitch when your follower is coming up. For example, if the climbing starts off easy and then gets hard for the final part of the route, you could have your follower in auto lock mode for the easy part, and then simply remove the blocking carabiner when they get to the crux, so you have an option to lower them if necessary.

Or, you can belay mostly without the auto lock. If you need to put on a jacket, sort out the ropes, take a photo, whatever, you can put it into lock mode, do your business, and then remove the locker and go back to normal. Can't do that with any other type of belay device that I can think of.

Be sure the hitch is set up in “raise” mode before you clip the blocking carabiner.

Test this before your follower begins, to be sure it is locking up properly.

One handy use for this knot is for light hauling, such as a backpack or light haul bag. The blocking function serves to capture the progress of your haul. Typically, another semi-obscure knot called the garda hitch would be used in this situation, but many people find this knot to be, shall we say, temperamental.

Another use of the auto locking munter hitch is to climb a rope. If you're short on gear, like a plaquette style device (Reverso), Grigri, extra friction hitch, etc., the auto lock munter can be your progress capture on your harness. This is definitely a trick use of the knot and something you wanna practice in a controlled environment before you ever use it for real!

This knot suffers from the same general problem as a standard plaquette device like the Petzl Reverso: if your follower is weighting the rope and needs to be lowered, you can’t easily do so.

By far the easiest way to transition to lowering mode is to have your follower unweight the rope just enough for you to unclip the blocking carabiner from the load strand. Once the carabiner is gone, you’re back to a normal Munter hitch, and can easily lower your follower.

If that’s not possible, there is in fact a way to release this when loaded. Use a small locking carabiner for the blocking carabiner. Unclip the loaded rope from the blocking carabiner. This should allow the hitch to flip into lowering mode, and the small carabiner should pass through the large carabiner. Having a third hand autoblock backup on the brake strand before you do this is highly recommended. Yes, this is kind of clunky, and it's probably better to avoid that situation in the first place, but it is possible.

As stated clearly at the top of this post, please practice this in a controlled environment before you ever do it in real life!

Here's a nice video on how to do this.

Here’s a second method, which results in less friction. Depending on your rope, this might be a big help. Watch the video for the whole scoop. (Start about 2:00 for the action.)

At first glance it looks like a bit of a mess, but it works remarkably well.

Crevasse Rescue - skip the munter mule overhand

The munter mule overhand, or MMO knot, is a load releasable hitch. While it can be helpful in advanced rope rescue scenarios, it’s not required in crevasse rescue, and in the opinion of various experts, does not need to be taught to beginners.

Or, “just say no to the MMO”

Short version: In my opinion (and that of many experts) the munter mule overhand knot (from here on referred to as the MMO) is not a required component of a crevasse rescue system. Including it in a beginner crevasse rescue class adds further unnecessary complexity to an already very complicated situation. It’s fine when taught to intermediate or advanced climbers, and it certainly has a place in more advanced rescue scenarios, but it’s probably best not to teach it to newer climbers.

Long version: You’re considering taking a class in crevasse rescue from your local mountaineering club. You read the class curriculum online, and see that requires that you tie an MMO knot at the anchor to make a “releasable system”.

In addition, the generally always awesome and hilarious cartoon book, “Glacier Mountaineering: An Illustrated Guide to Glacier Travel and Crevasse Rescue”, says to use one also.

Conversely, the following reputable sources do NOT suggest using an MMO for crevasse rescue:

Book: “The Freedom of the Hills”

Book: “The Mountain Guide Manual” a reference book for, you guessed it, professional guides

The American Alpine Institute (AAI, see their crevasse rescue sequence here.)

YouTube instructional videos presented by professional mountain guides

The munter mule overhand with a cordelette

(Note: Mule knot not snugged up against Munter hitch to show the various parts more clearly. Carabiner through the overhand knot for extra credit.)

So, what’s the dealio, you may be wondering. Do I really need an MMO for crevasse rescue, or not?

To help answer this, ask yourself a few questions.

Is the MMO a seldom used, specialized rescue knot, that’s tricky for most people, especially beginners, to tie correctly? Answer, yes.

Is it likely that you’re going to forget how to tie a seldom used, specialized rescue knot, that you never use in your day-to-day climbing, years from in a rescue scenario that’s already stressful and complicated? Answer, yes.

Is it possible to rig a successful mechanical advantage crevasse rescue system without using this knot? Answer, yes.

Are the vast majority of crevasse rescues performed by raising only, without ever needing to lower at all? Answer, yes.

Is it possible to lower a victim safely (if for some reason you need to) without having an MMO in the system? Answer, yes.

I’ve watched several crevasse rescue videos made by AMGA (American Mountain Guide Association) certified guides on YouTube, and none of them use an MMO. Why is this? Probable answer - see the previous five questions.

(If you watch the excellent crevasse rescue videos made by AMGA certified guides that you’ll find on the video portion of AlpineSavvy, nowhere do you see this knot.)

Additional note: The MMO, as it’s usually taught, requires a cordelette. Which is probably okay if you have three or more people on your rope team and everyone has one. But if you’re a two person team, you probably already used your cordlette to build the 2 piece anchor, so you don’t have a second one for the MMO.

Let’s get back to the purpose of having an MMO in the first place, which is to have a “releasable system”. Why is this needed?

Typical answer - if the person in the crevasse needs to be lowered, the releasable system lets you do so. Reality - if you want to lower them, all you need to is pull about 1 inch up on the whole raising system, loosen the holding prusik, then lower. You can easily do this without the complications of an MMO.

(There is one additional highly unlikely rescue scenario, and that’s if the hauling team on top gets over enthusiastic, does not monitor the fallen climber during the pull, and somehow manages the epic screwup of pulling the fallen climber into the lip of the crevasse. In this case, theoretically, you may not even be able to get 1 inch more lift out of the raising system to loosen the prusik initiate the lower.)

Well, there is a way to do it. It involves getting out your knife and VERY carefully cutting that prusik knot, thus removing it from the system and getting your victim out of the problem that you caused. In this rare case, it could be argued that a MMO would be a superior solution, but it’s so unlikely to ever happen that in my mind it’s not worth planning for.

Takeaway: the MMO component of a crevasse rescue system is entirely optional, and in a beginner level class, adds needless complexity and a difficult-to-remember component to an already stressful and challenging situation.

Most people starting to learn crevasse rescue have their heads completely full with the steps that REALLY need to happen. Thus, most people don’t have any room for anything optional or overly complicated, or in this case both.

Once you have the basic crevasse rescue skills down, or certainly if you’re on a professional mountain rescue team, then you can start adding in more advanced components such as two person rescue and releasable systems. But for beginners, teach the basics, make sure they understand it inside and out, and keep it simple.

That's probably why “Freedom of the Hills and “The Mountain Guide Manual” don’t teach it.

Just say no to the MMO.

Spot, don’t belay, before the first clip

When does a good belayer not belay? Before their partner has made the first clip. Avoid this common beginner mistake.

An all too common scenario at beginner climbing areas is a new belayer attentively clutching the rope with both hands, while their partner is sketching upwards toward the first bolt or gear placement.

Until the leader clips the first bolt or gear, your job as belayer to spot them like they’re bouldering. Both your hands should be up, thumbs tucked into your palm, and your main task is to keep their head from hitting the ground should they fall before they clip.

Anticipate how much rope is needed from the ground to the first clip or placement, and feed enough rope through your belay device so the leader is never restrained while moving or clipping.

The moment they clip, you instantly change to belay mode, with your hand on the brake and feeding rope as usual.

Of course, this is a non-issue if you’re using a stick clip when sport climbing to attach the rope to the first bolt.

Here’s (more or less) how to do it. Note the climbing rope in the right hand, ready to return to belay mode right after the leader makes the first clip.

image: from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S_F1MfVGOzk

And this video, starting about 1: 32

Assorted "vertical camping" tips

Big wall climbing can offer enough suffering when you're actually moving upwards. Once you reach the bivy, you’ve earned a little comfort. Here are some tips from wall expert Mark Hudon to stay warm, dry and cozy.

Many of these tips are from Mark Hudon, a Yosemite big wall veteran. His systems are thoughtful, dialed, and generously explained both on his website and various online forums. The following collection of tips were mostly taken from a post on his website. You can read the entire thing at hudonpanos.com. Here, I'm posting the ones that seem especially brilliant, but I encourage you to go to his site and read the whole article.

See related post - Portaledge set up - Top Tips

Each climber has their own separate haul bag. Mark likes the Metolius Half Dome, about 125 liters. If you are a little taller, you can get the next size up which is only a little bit more in cost and weight. (Here's another post about had to choose a haulbag.)

You want to minimize rummaging around in the bag during the day when you’re climbing. Before you leave your bivy in the morning, pull out items you think you might need to access during the day and keep those handy. This might include snacks, water, lip balm, sunscreen, wind shell, warm hat, visor cap, and camera/phone. Keep these in a wall bucket or sturdy small big wall bag like a Fish Gear Beef Bag that hangs outside of the haul bag on a gear tether cord.

Mark has a comprehensive clothing list, see his website for details. All fleece and synthetic; no down, no cotton. He keeps it all in two separate size large Metolius Big Wall Stuff sacks. These bags are stout, have nice clip in points, are fairly inexpensive, and (best of all) from a company based in Bend, Oregon (my home state).

Mark organizes his core equipment into five different color coded stuff sacks: clothing (2 sacks) kitchen, food, personal care, and technology. This makes pulling out exactly what you need from the bottom of the haul bag a lot easier. (Any small item will migrate to the bottom of the bag unless it’s clipped to something or in a stuff sack.) Every stuff sack has a carabiner clipped to it.

Personal care bag: Mostly small stuff to deal with the constant dings and cuts that are going to happen to your fingers. Athletic tape, Advil, sunscreen, hand lotion, earplugs, unscented baby wipes, and paper towels instead of toilet paper. A little Bag Balm underneath a Band-Aid can really help heal your hands overnight. Take care of little cuts early before they become a larger problem.

Technology bag: phone, maybe a Bluetooth speaker, maybe a Kindle reader, all fully charged up, fully charged large spare battery and needed charging cables, headlamp with spare battery, camera, 2 way radio.

Once your ledge is set up, bring all of your stuff sacks out of the haul bag and clip them to your ledge. You want everything close at hand and avoid burrowing in the bag any more than necessary. You will need 8-10 spare “bivy” carabiners for this, so be sure and bring some. It's helpful to make these bivy carabiners all one obvious color or strange style that you don't use for climbing. Some people even mark them with spray paint.

Bring a multitool. A decent sized one, with good needle nose pliers. If you need to untie a welded knot, that's gonna be your best friend. Along with a good knife blade, bottle opener, maybe a can opener. (I heard a story of some guys who went up El Cap with a bunch of canned food, and somebody forgot the can opener, whooooops!)

Everything needs a clip in point. If it doesn't have one, you're going to lose it. Tie these at home if possible, and bring extra small diameter cord to improvise as needed. Bank line, a sort of heavy duty black twine rated to over 300 pounds, is an excellent choice for adding tie in loops.

Everything has its own designated carabiner. Anything you're gonna need on your bivy / ledge has to have both a clipping point and designated carabiner that lives on it. Attach the clipping point and get those carabiners at home. Smaller wiregate carabiners, like Camp Nano or Metolius Mini work great. I like to buy these all in the same unique color, so they don't get mixed up with the main climbing rack. I prefer carabiners properly rated for climbing, not keychain carabiners from the hardware store.

Consider using an old-school sewn daisy chain with pockets (photo at top) to help organize your belay. Having a confusing cluster at your anchor is stressful, because you are never quite sure what you can safely unclip. By using a dedicated sewn daisy chain(s) to clip things like rope bags, water bottles, etc, you can have a much cleaner and more manageable belay. Read more on this here.

Once your ledge is set up, try using a separate length of rope to tie your harness to the anchor, rather than the climbing rope itself. Get 6-7 meters of some old rope (about 8-9 mm) that's only used to tie you to some solid point on the anchor once everything is set up. Tie one end to the anchor, tie a barrel/stopper knot on the other end, and use your Grigri or a friction hitch to adjust your position as you move around the anchor. You certainly don't need to use all 20 feet, but if you're at a larger ledge, you want to be able to freely move around. This lets you tuck away all your lead rope to keep things a bit more tidy.

You generate a surprising amount of garbage on a big wall climb. You need a plan to deal with it. Having some sort of extra stout bag or stuff sack will be needed. It's easy to overlook this, ask me how I know. You can hang this below your main haul bags on a gear tether.

If the weather is hot, taking a midday siesta to avoid the sun can be a great idea. Bring earplugs and an eye mask to help you take a nap.

Do NOT bring a down sleeping bag, regardless of how sunny the weather forecast might be.

Having a thin fleece sleeping bag liner gives warmth and feels great against your dirty skin. Having a bivy sack offers further moisture protection for your bag and makes it warmer.

If you’re warm and dry in your portaledge, do everything you possibly can to stay that way. Anything that gets wet on a big wall is probably going to stay that way for a while. That means not going outside into the rain to fix another pitch unless you absolutely have to.

Many modern ledges have flies with some rigging to keep them away from your face. If yours does not, bring a tent pole that you can rig inside the fly to help push it away from you, so you have a bit more room.

Speaking of staying dry in your ledge, bring a sponge to mop up spills, drips or condensation inside your fly.

Metolius Big Wall Stuff Sacks, perfect for organizing your vertical camping.

image: https://www.metoliusclimbing.com/big_wall_stuff_sacks.html

Girth hitch a cam hook to your aider

Cam hooks, while they may appear about as secure as a tortilla chip, are essential tools for modern clean aid climbing. Here’s a trick for deploying them that offers convenience and extra reach.

The humble cam hook is an essential modern aid climbing tool for moving quickly in crack systems that are generally too narrow for spring loaded cams; i.e., slightly smaller than Donald Trump's pinky finger.

Instead of fiddling with a micro stopper or (gasp!) banging in a piton, just slot a cam hook vertically into that micro crack, carefully step onto it, and it magically locks itself into place. The first few times you won't quite believe that it actually is going to hold, but your trust and confidence will grow quickly.

Repeat as needed by alternating your aiders, and when the runout starts getting spooky, then put in solid gear. (That little stopper you place with a gentle tug for fall protection will be a lot easier for your second to clean than one you have bounce tested with your full weight.)

It's best not to bounce test cam hook placements if you’re doing several in a row. Just ease onto the upper placement with a firm step into the aider, and move up.

You want to buy at least two cam hooks, one for each aider. Fortunately they are quite inexpensive. MountainTools is a fine place to score some. They come in four sizes, with the middle two generally being the most useful. Pictured below is I think the Leeper medium, which has worked well for me.

Note that cam hooks are generally not used in soft rock like sandstone, because the force they can generate can literally break the rock. The smaller size hook, the more force is generated. Apparently the newer cam hooks made by Moses have a model called “fragile flake” that’s acceptable for use in softer rock, but I haven’t used them.

The typical way to deploy cam hooks is to have them on a short loop of webbing, and clip them to the top of your aiders when you need to use it. (Like this; a perfect placement in my wooden deck!) Yes, that webbing loop could be about 2 inches shorter, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

However, here’s an alternate set up - if you anticipate a lot of cam hooking, you can girth hitch the hook directly to the top loop of your aider. like this:

This offers a few benefits.

You can deploy your hook fast; no reaching for gear on your harness

You get a few extra inches of reach on the placement, because there’s no carabiner involved

You can never drop the hook

You could tie the hook directly into the top of your aider. However, this makes the hook pretty much permanently attached to the aider, because the water knot connecting the webbing is going to get welded. Aid climbing is confusing and clustered enough without adding anything unnecessary into the equation, so in climbing where you don’t need the hook, it’s cleaner and tidier NOT to have it always on the business end of your aider.

With a girth hitch, the cam hook is ready to use fast when you need it, but is easily removed when you don't.

To rig this, get 18 inches of 1/2 inch webbing for each hook (or 3 feet for 2 hooks). Yes, this looks like a lot of webbing, and you may have an inch or so left over, but those darn water knots always seem to take more webbing and than you think.

Tie a water knot through the cam hole to make a loop, that's a half inch or so longer than the length of the cam. You’ll probably have to experiment a couple of times to get this loop just the right size. If the loop is too big, you lose reach on every placement. If the loop is too small, you won't be able to girth hitch it.

Water knots are notorious for loosening under repeated cycling loads, so tighten down the knot with a pair of pliers, and check it often to be sure it's not loosening up.

The original and classic cam hooks were made by Ed Leeper, so they are sometimes referred to as Leeper hooks. They are now manufactured by Moses, and available through various outdoor retailers, such as MountainTools.

Here’s a nice video that shows the basics of using cam hooks.

Adding friction to a rappel

Cold hands, no gloves, skinny rope, wet rope, beginners, heavy pack . . . or some combination! There are many scenarios when you might want to add some extra friction onto a rappel. Here are a few ways.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

Sure, on a bluebird day, standard rappel practice is probably going to work fine. However, some rappel situations, such as:

a single strand

wet/icy rope

skinny rope

cold hands

no gloves

forgot your third hand friction hitch backup

wearing a heavy pack or dangling a haulbag

a rescue where you have the weight of 2 climbers on the rappel rope

dark

an icy, slippery slab

a knuckle scraping overhang

not sure where the next anchors are, need to go slowly and look around

or any multiple combination of these cluster factors, can make adding some friction a fine idea.

Raps under Less Than Ideal conditions are often safer and easier when you add extra friction to the rap to better control your descent speed. This can be especially true for beginners, who most of the time are happy to go down a little more slowly under greater control.

Note, using these techniques does not replace having a third hand backup autoblock.

Note: It is critically important that you always use a rappel device that is properly sized for your rope.

This is especially true if you are using twin or half ropes. Many accidents have happened when people have started to slide uncontrollably when they had a skinny rope in a rappel device designed for something larger. The techniques below do not replace having the correct rappel device to begin with.

Here are a few easy ways to add friction to a rappel.

Note - Method 3 is my favorite, because it's more easily adjustable on the fly. Need just a little bit of extra friction? Redirect the brake strand through the bottom carabiner. Need even more friction? Redirect the brake strand through the top carabiner.

Methods 3 is what we might call “adjustable”. Meaning, you can have the carabiners in place, ready to go in case you need them. If you find your rap is going faster than you like, you can then use them. Because rappels get faster near the bottom when there is less rope weight, this can be a good approach.

1) Use TWO carabiners and clip the rope through both.

The extra friction of the second carabiner slows your descent. This may be counterintuitive, as it seems that the sharper angle made by a single carabiner would slow the rope more. It’s actually the opposite - try it yourself and see. This second carabiner does not necessarily need to be locking, and it does not have to be clipped to your belay loop.

Lots of pro guides advocate this technique, but personally I‘ve found it doesn’t make much of a difference.

Bonus tip - if you find yourself having to belay on a skinny rope with a belay device that's not quite rated for it, you can use this same “double belay carabiner” trick to add a bit more friction. (Ideally, you should never find yourself in this situation . . .)

2) Clip a spare carabiner to your device’s “ear”, then to the belay loop.

If you have a plaquette style belay device such as a DMM Pivot or ATC Guide, try this: feed the rope as for a normal rappel. Clip a spare carabiner (non locker is fine) through the “ear” of the device, then clip that carabiner to your belay loop. Doing this changes the braking angle of the device, increasing friction.

Note: The effectiveness of this has a lot to do with the rope diameter, how slippery the sheath is, and the size of the carabiners you’re using. This might be the perfect solution, it may only give a tiny bit of increased friction at all, or it may completely lock up your device. Definitely practice this one on a staircase first!

Note, if you’re rappelling from a sling with an extended rappel, can you clip this year back to your belay loop, you will immediately lock up your device and be in ascending mode. Which at times can be super helpful! Learn more at this article.

3) “Rappel Z” with an extended rappel

This is pretty hard to describe in words, so check out the diagram below.

This has the advantage of working with an autoblock backup, if you choose to use it. Note that you need to attach the autoblock to the leg loop, and it might also add an unnecessary extra amount of friction and cluster. As always, practice in a controlled situation, like a staircase, before you use it for real.

image: “Self Rescue”, by DAvid Fasulo, illustration by Mike CLelland

Snow anchors: how strong are they?

Sinking a snow picket and having a few people try to pull it out is kind of fun . . . but not very scientific. The French national guide school did some real world pull tests on snow anchors, and there are a few good takeaways.

Here’s another “tres bien” video from ENSA (“École Nationale de Ski et d'Alpinisme”, or the French National Guide School) where they take engineering tools out into the real world and see how climbing gear and technique really work. (Video link at bottom of page.)

If you haven't seen it yet, be sure and watch this other great video, where they test the usefulness of brake knots in the rope for two person crevasse rescue.

In the mountains near Chamonix, they rigged some pull tests on all manner of snow anchors, some traditional (pickets, snow bollard, ice axes, vertical and horizontal skis), and some unconventional (plastic bags, soda bottle).

Here are some takeaways:

Placing a vertical anchor, like a picket, at a 25° angle leaning away from the direction of pull makes the anchor approximately 40% stronger. (See graphic below.)

Even in a buried plastic bag and a soda bottle held 200+ kg, more than enough to rappel from. (I still think I'd let my friend go first . . .)

From the 2010 International Snow Science Workshop, a paper called “Snow anchors for Belaying and Rescue”, by Don Bogie (New Zealand) and Art Fortini, (USA) is probably the most detailed study on snow anchor strength. It states (pg. 315): "In order to allow some room for error when placing a stake it is recommended that when placing upright mid clips that an angle of 30 degrees back from perpendicular is used.”

So, somewhere in the neighborhood of 30° is probably optimal.

image: screen grab from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yYtYZgeUpek

There’s a nice chart near the end that summarizes all of the data. (The fourth column, “strength in daN”, means “dekanewton”, a metric unit of force. It's 0.01 kN, or approximately the same as 1 kg of force.)

image: screen grab from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yYtYZgeUpek

Finally, for a very deep dive into snow anchors, here’s a training video for the Mountain Rescue Association featuring a presentation from snow anchor expert Art Fortini.

Top reasons why “hydration systems” are Less Than Ideal

Lots of people use water bladders, but they have a host of downsides that are rarely considered. Here's a list of why water bladders really do “suck”.

Everyone agrees that keeping properly hydrated is important in any endurance sport. But do you really need a so-called “hydration system” to do this? While water bladder / reservoirs can work for mountain biking and day hiking, they have a host of downsides you may want to consider before you take one on your next long hike, trek or alpine climb.

The tubes can freeze.

There are many delicate parts (tubes, bladders, mouthpiece bite valves) that can easily break or malfunction, and they’re hard to repair in the field.

They have lots of hard to clean cracks and crevices where funky microorganisms can grow.

They’re hard to fill, either from streams or with snow.

It’s difficult to monitor your water consumption and see how much you have left.

It’s hard to share water with others.

Depending on the design of your pack, you may have to empty out a good chunk of it to remove and refill the reservoir.

The mouthpiece can easily drag in the dirt when you put your pack on the ground, yuck.

You can’t use a reservoir in camp as a cup for hot drinks.

You can’t put hot water in a reservoir and put a sock over it at night, to help dry out wet socks.

They’re very expensive compared to a simple water bottle.

Bonus reason: Unless you’re in some sort of a race/competition, are you REALLY in that much of a hurry that you can’t stop for a minute or two and drink some water?

So, how to stay well watered on the go? A simple water bottle.

Get a small ultralight mesh bag and attach it to your pack shoulder strap. (Search Etsy for “backpack water bottle holder”, or try this Etsy store.

Put a water bottle in one of the stretchy mesh pockets on the side of your pack, a feature of many packs designed for backpacking. If it's hot, start your trip with larger bottle(s) inside your pack, and refill the small bottle at breaks. This lets you drink on the move as effectively as a bladder system, with none of the cost and hassles.

Don't get a Nalgene bottle, those are too heavy (about 7 ounces empty). Simply re-purpose most any empty water or juice bottle. Smart water bottles are popular, they are tall, skinny, and have fairly sturdy plastic. Personally, I am a fan of the 20 ounce Gatorade bottle.

Oh, and, check the water bottle aisle next time you’re in REI. Camelback sells, you guessed, it, a simple water bottle (complete with large Camelback logo.) A tad ironic, no?

Related story: A friend of mine went on a trekking expedition to Tibet. The trekking company explicitly told everyone on the trip NOT to bring water reservoirs with a tube. Reason: The trails were also used by pack animals such as yaks. Yaks poop everywhere. The sun and low humidity dries out the yak poop, and then the poop pulverizes into tiny particles from the feet of people and animals. The floating yak poop powder then settles on, you guessed it, your drinking tube, YUCK! They found that many Westerners were getting sick on their trips. When they had guests change to a simple water bottle, the illness rate went way down.

Finally, here's what world-class alpinist Steve House thinks about water bladders.

(Can you imagine planning and saving money for months for an expedition, traveling halfway around the world to a remote serious mountain, and then bailing because your water bladder leaked all over?!)

Use a tarp for a quick snow shelter

Carrying a tarp is not only for shelter; it does extra duty as a first aid and rescue tool. Here's a slick way to make an emergency snow trench shelter with a tarp.

This tip comes courtesy of the Jackson Hole Outdoor Leadership Institute.

The photos were first published in this Facebook post.

Carrying a lightweight tarp as part of your emergency shelter system is an excellent idea for lots of reasons. In addition to the obvious tent-like shelter to sleep in, here are a few other options.

Lunchtime quick shelter for you and a small group (sit on your packs and pull the tarp over you.)

Package an injured person and drag them out in snow

Outer layer of “thermal burrito wrap” to package an hypothermic or injured patient with foam pads and sleeping bags / warm clothing while you wait for rescue in a cold environment

Extra layer over a simple bivy bag, offering more protection for your upper body and some covered room to move around

For today's post, it's a key component of a snow trench winter shelter.

The basic concept is simple, and the photos below show it pretty well, but here's a step-by-step. (The photos below are for people with ski touring equipment, but if you don't have it you can improvise.)

Dig a rectangular hole that's wide enough for you and your ski buddy, and about 4 feet deep. (If the snow isn't that deep, you can excavate down to bare ground and then build up walls on three sides.)

Place your skis across the top (If you’re below timberline and don't have skis, branches would work also)

Put your tarp over the skis. ( A 7’ by 9’ tarp is about the minimum size you can use; ask me how I know this!)

Use your ski poles (or branches) to anchor the four corners of the tarp.

Pack some around the edges of the tarp.

Dig a separate access hole, and carefully build an arch / hole so you can get in and out of your trench.

If you have an proper sleeping bag and sleeping pad, you're all set. If you don't, you better dust off your bushcraft skills, and go collect a bunch of conifer boughs to place under you for insulation, and on the side to keep snow from falling in on you.

There you go! Fast, reasonably comfy, and constructed without any advanced igloo building skills or getting sopping wet from trying to dig a snow cave.

photo: https://www.facebook.com/JHOutdoorLeadership/posts/1920166718037956

photo: https://www.facebook.com/JHOutdoorLeadership/posts/1920166718037956

There are lots of good quality tarps out there.

Ski rescue sled tarps

If you spend a lot of time backcountry skiing, you might want to carry a rescue tarp. Use it as a quick lunchtime shelter, a more serious overnight pit shelter, and a toboggan-style rescue sled. Check out the one below, made in Seattle by High Mountain Gear.

Use the discount code ALPINESAVVY10 to get a 10% discount from High Mountain Gear.

High mountain gear ski guide sled tarp. Photo: https://highmtngear.com/

High mountain gear ski guide sled tarp. Photo: https://highmtngear.com/

Here's a tarp I have that I like a lot, the Pariah Sanctuary Sil tarp. The main thing I like is the price.

Note that the link below will show you tarps in several shapes and sizes. I have the 8’ x 10’ “flat cut rectangle”. The sewn tabs at the the 16 tie out points are well made, and it comes with all the goodies you need to set it up, including six ultralight stakes, 60 feet of 1.5mm Dyneema guy line and a carrying stuff sack.

(And note how to pronounce the name = “Pariah” is pronounced like the woman's named, “Maria”.)

DIY - Make a rug from a retired climbing rope

Your trusty climbing rope has served you well, and deserves a better fate than to be cut up into dog leashes. Make a rug out of it instead.

Got a newly retired climbing rope? Feeling crafty? Turn that rope into a lovely rug.

As always, YouTube is your friend.

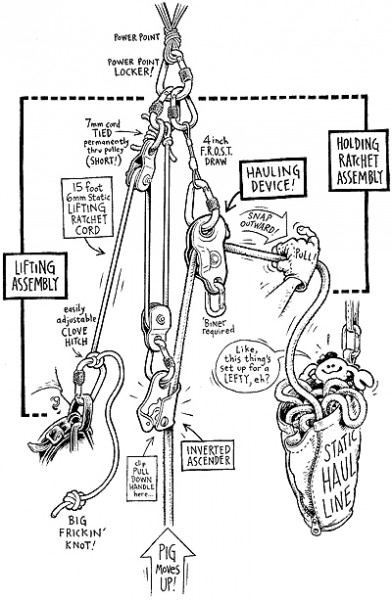

The 2 to 1 “Z pull” haul, explained

On a longer big wall, with bigger loads, using mechanical advantage to lift your haul bags can be extremely helpful. Here's a deep dive into the 2 to 1 hauling system.

Credits for this idea, as best I can. The 2:1 Z pull haul is generally attributed to Chongo, a legendary Yosemite dirtbag who was famous for extended vertical camping trips on El Capitan with ridiculously large loads. Pete Zabrok, also no stranger to multiple week outings on the captain with huge loads, popularized it via a 2004 Tech Tip in Climbing magazine, and now climbers such as Mark Hudon have refined it further.

This technique is explained nicely in the comprehensive aid climbing manual “Hooking Up, by Pete Zabrok and Fabio Elli, highly recommended for all big wall climbers!

A few words on hauling, from the excellent book “Higher Education” by Andy Kirkpatrick.

“Hauling is potentially one of the most dangerous aspects of big wall climbing. This translates to ultra-caution in all parts of your hauling system and interaction with bags, haul lines, docking cords, and pulleys. If you rush and make a mistake, drop a load or have it shift where it's not wanted, you could easily kill someone or yourself. I try and teach climbers to view their bags as dangerous creatures, like a great white shark, rhino, or raptor that is in their charge. The ability to keep them calm and under your control comes down to paranoia, foresight, and heavy respect for the damage they can do.”

Think before you act. Before you connect or disconnect anything, always think a step or two ahead and anticipate what will happen and potential problems. “If I untie this docking cord, then the load is going to go there, and after that happens, I’m going to do this . . . ”

On big wall climbs taking two or three days with a team of two, you can probably use a traditional 1:1 hauling system. However, for climbs much longer than this, or a team of three, or when you or your teammate are significantly lighter than the bags, or if the hauling is on terrain less then vertical, or maybe when you simply want to suffer a lot less, you may well want to add some mechanical advantage. As the saying goes, you can work hard, or you can work smart. For a big load, a 2:1 haul is working smart. (If you’re taking a truly ridiculous amount of stuff and need a 3:1 or 4:1, you're probably an expert enough climber to figure that out on your own, so I'm not going to cover that here.)

Say you have a pair of haul bags that together weigh 200 pounds. If you rig a 2:1 haul, you (theoretically) can lift this load with only 100 pounds of force. The catch is, you have to pull twice as much rope in order to get the load to the anchor, but for many people that’s a fine trade off to make. Think of it this way: do you want to lift 200 pounds once, or 100 pounds twice?

Now, there is Google-load of information out there about 2:1 haul systems. But like most things on the interweb, especially discussion forums, the signal to noise ratio is not so great; you’ll have to wade through pages of the usual randomness to get anything worthwhile.

Well, good news you you, I’ve taken care of the sorting and sifting. This post is a summary of current (2020) best practices, clear photos, and some specific gear reccos for the 2:1 big wall haul.

I’ll be honest, the first time I saw this I found it pretty darn confusing, and wondered if it was really worth it. But once you get the components arranged correctly, and give a little thought to what is happening, and try some real world testing, you’ll get the hang of it. And, hopefully you will never have to use that all too common excuse for bailing, “The bags were too heavy . . .”

One of the best climbing diagrams ever made, IMHO. Drawing by Mike Clelland, first published in Climbing magazine (March 2004) article written by Pete Zabrok. Note, while the system has been refined in several areas since it was first published, this is still the core idea.

image credit: Mike Clelland

Big picture concepts:

Minimize stretch wherever possible

Use high quality/efficiency pulleys

Lift the load by doing squats using your body weight or pushing down with your legs, not by pulling with your arms

Practice a lot with real loads

Get it set up fast and haul the bags a few meters off the lower anchor ASAP so your follower can get to work

The basic set up is a 1:1 haul through a progress capturing pulley, such a Petzl Traxion. (This is a pulley that has a one-way rope grab on it like an ascender, that let you pull the rope through one direction but prevents it from sliding back.) Yes, these little suckers are expen$ive!

On the load strand of the haul line, you add on an entirely separate 2:1 lifting system. You raise the load with the 2:1 lifting system, and then pull the slack rope through the progress capture pulley.

In the rigging world, this is sometimes referred to as a “pig rig”, because you are “piggybacking” a 2-1 system on top of the main loaded rope. (And, that’s an entirely appropriate name for big wall climbing, because haul bags are affectionately known as “pigs”.)

One nice benefit to this system: you can add or remove the “pig rig” from either a slack or tensioned rope, which lets you switch as needed in the middle of a haul.

General diagram of a 2:1 “pig rig”. (The black rope is the main static haul line. The gray cord is the 2-1 “Z cord.” Tilt your head to the left; it looks like a letter Z, get it?)

In the diagram below, the system is spread out over two anchors. It also works fine on one.

(Note: if you've taken a crevasse rescue or rope rescue class, you might think of a “Z drag” as being a 3:1 mechanical advantage. That is correct. However, in this case, the “Z” is a 2:1 system, with a change of direction pulley, as you can see below. Trust me, it's 2:1, don't let the “Z” in the name confuse you.)

Here's how it works.

The hauler pulls down on the gray cord, maybe by squatting in the harness.

This lifts the black rope, creating slack.

Pull that slack through with your hand, capturing the progress with the pulley on the right anchor.

Repeat!

Image credit: Andy Kirkpatrick, from his excellent book “Higher Education”, used with permission

There are various ways to rig a 2-1 haul. Here's one.

Components

All parts live in a designated small stuff sack and stay clipped together between hauls, ready to deploy.

Large HMS locking “master point” carabiner

Short Dyneema dogbone quickdraw runner (hard to see in the photo, sorry.) Zero stretch, important! This could also be a large stopper or custom made metal quickdraw. This allows the carabiner and progress capture pulley below it (3 & 4) to rotate and align when pulling.

Locking carabiner

Progress capture pulley, here a Petzl Mini Traxion

The “tractor” pulley, so called because it’s doing the work

Quicklink, I think 8mm

Inverted ascender, here a Petzl Croll. Could be a Petzl Basic or similar small ascender without a handle.

The haulbag(s), aka “the pig”

Haul line, typically 70 meter, 10 mm, static rope

Handled ascender. Add this to the “pulldown” side of the haul line to make it easier on your tired wall hands. But remember, you want to be doing most of the hauling with your bodyweight and not your arms.

The Z cord - 7 mm cord, start with about 5 meters. If you find you have too much extra cord, trim some off. Could be a thinner 5.5 mm static spectra cord for a slightly more efficient pull. Be sure and tie a large stopper knot on the end to prevent your hardware from sliding off accidentally. (Pro tip, bring a second spare Z cord, in case the first one gets trashed.)

The “redirect” pulley, so called because redirects the Z cord downwards so you can use your body weight to lift. This pulley does not add any mechanical advantage. This should be a high quality pulley, see examples below.

Small loop of 11/16” webbing tied through the pulley. This webbing connection, rather than a carabiner, allows the redirect pulley to freely rotate and give a more efficient pull. It’s important to have this webbing loop small so the redirect carabiner is high, which gives you a longer, more efficient pulling stroke.

Not shown: Two carabiners with rounded cross sections on your belay loop. When you’re hauling, you can clove hitch the orange Z cord to both of these carabiners. Having two of them makes untying the loaded clove hitch easier. Old school oval carabiners work fine.

Another option is to clip an ascender with a stirrup of webbing or an aid ladder onto the Z cord, and pump down on the Z cord with your leg.

Here’s another way to rig this. Note the redirect pulley (orange) with an integrated swivel, smaller diameter static Z cord, a cable quick draw (zero stretch) and a Petzl Basic ascender. This looks a little simpler without the haul rope, but it's the same basic idea.

image: https://www.mountainproject.com/forum/topic/115790897/the-latest-greatest-21-hauling-kit

Side note: You might be tempted to use a rigging plate clipped to the master carabiner, because it has three things clipped to it and it's getting kind of busy. This would be a mistake. Reason being, that rigging plate is going to rock back-and-forth as it's loaded and unloaded on different sides, which will decrease your hauling efficiency.

Rigging plate - Do NOT use it in your 2-1 hauling system.

One of the beauties of the 2 to 1 haul kit is that you can set it up pretty much once, keep most of the components clipped together in the correct order, and leave it that way. It has its own small designated sturdy stuff sack (medium sized Fish “Beef Bag” works great). The haul kit is never taken apart, and is either being used or in the storage bag. Note that the hauling system hardware always stays clipped to the storage bag; can’t drop the bag if you do this.

Note that the leader does not have to take the haul kit up with them on lead. The leader can trail a tagline, and bring up the haul kit once they arrive at the anchor. Doing this saves weight and cluster on your harness. More on using taglines here.

At the belay, here’s what you do:

Build an equalized master point anchor from 2 bolts. (If the bolts look newish and extra stout, you can haul off just one, but I’ll leave that choice to you. Me, I like 2 bolts.) Use an “anchor kit” of several large locking carabiners, and maybe a pre-tied quad anchor or PAS that you and your partner can set up fast and the same way pretty much every time.

Clip the master point carabiner for the Z haul system to the anchor master point (or lone hauling bolt).

Run the haul rope through the progress capture pulley, engage the cam, and pull all the slack through the pulley. Then clip on the inverted ascender. Hopefully you have a rope bag; now would be a good time to start using it to stack the haul rope.

Extend your daisies or connection to the anchor so you are free to move. Find yourself a good stance and adjust the Z cord with the clove hitch on your harness. (Altenatively, clip an ascender to the Z cord, clip on an aid ladder, and press down with your leg.)

Start lifting your bags a few meters, so your partner below can get busy breaking down the anchor. (Once the bags have been lifted off the lower anchor, ONLY THEN you can take a break for a minute or two before you start the real hauling.)

A few notes . . .

As pointed out to me by wall ace Mark Hudon: Yes, you may be theoretically 2:1 efficient, but that can also mean 2:1 inefficient. Meaning, if you have 1 inch of slack in your lifting system, you’re actually losing 2 inches of lift with every stroke. When you push the lifting ascender down, be sure to Z cord comes tight to the clove hitch to your harness so there is no slack. Squat with your body weight. If you doing it right, there should be no pulling or lifting with your arms at all.

Practice, practice, practice with this system. Go find a retaining wall, a tree, a fire escape, an outside staircase, whatever, and load up a haul bag with water bottles or bricks or rocks, and really give it a work out. Which way should the master carabiner face (left or right off the bolt hanger) to be most efficient for you? Do you want to have the inverted ascender by your dominant hand or your weaker hand? How long exactly should the Z cord be? (This changes depending on your stance.) These are some subtle yet important adjustments that can only be found with practice. Taking the time to dial in your system will pay big dividends on the wall.

It's usually less energy to do more small squats than fewer big ones. Doing short little strokes might seem like it's gonna take forever, but you're probably going to expand less energy in the long run.

Ideally, you want your strong/dominant hand on the inverted ascender, and your weaker/non-dominant hand pulling the slack rope through the progress capture pulley. So, in the cartoon diagram at the top, and the labeled photo, this is set up for a left handed person. Experiment with this and see what work for you.

Ideally, both pulleys should be high efficiency, with sealed ball bearings with 1.5 to 2 inch aluminum sheaves/wheels. These will cost about $40 each, don’t skimp on these. If you have one pulley that’s better quality and/or has a larger diameter wheel, use this as as redirect pulley, and use the smaller or lower quality pulley on the tractor. The reasons for this get into some engi-nerd territory, but trust me, this is the best way to rig it. (But, don’t be a cheapskate, just spend an extra 10 bucks or so, get two high quality pulleys, and then it’s not an issue at all.)

When shopping for pulleys, go for quality from major manufacturers such as SMC, Petzl or CMI; they are used a lot by professional riggers and rescue teams. Look at the technical specifications. Stay away from cheaper pulleys that have plastic wheels (aka sheave) or bronze or nylon bushings. You want an aluminium sheave and sealed ball bearings. A small inefficiency in a pulley is magnified many thousands of hauling strokes over a single route, so the difference between say 70% and 80% efficient is significant. Fortunately you can have lightweight, high efficiency pulleys, you just need to buy the right ones.

Mark Hudon likes the 2" Single PMP and the Micro Single PMP, both made by SMC (Seattle Manufacturing Company). Some other good options would be the Petzl Rescue pulley or the CMI RP102.

Prusik minding pulleys (also known by the acronym of PMP) tend to be more expensive that regular pulleys. You don’t need a PMP in this system, because there are no prusiks.

When hauling, remove everything from your harness gear loops. You want to minimize extra weight when you’re repeatedly squatting and standing.

Bring a spare Z cord. If you're doing this over a ledge, the cord might get damaged. Bring a spare.

Practice will not only help you haul more efficiently, but it will help you get set up faster. This is important, because your partner can’t start to break down the anchor and begin cleaning until you haul the bags at least a meter or two and get them off the previous anchor.

If the leader wants to be extra courteous and helpful, they can break down the hauling kit when the bags are safely docked, package it back up in its stuff sack, and hang it on the first piece of gear for the next pitch, so the new leader can be sure and grab it. (If the second is using a tagline to pull up the kit when they need it, then no need to hang it on gear for the next pitch.)

Just like with any hauling system, you want to minimize friction in any way you can. If you have the option, build your hauling anchor as high up as possible, and try to eliminate or minimize the angle at which the rope may run over any rock edges. If the pitch is overhanging, lucky you. If you're pulling the bags up a slab, then you're theoretical 2:1 is going to act more like a 1:1. Prepare to suffer.

Wear gloves for big wall hauling. The Metolius 3/4 finger climbing gloves are great.

Here’s a video of Mark Hudon using this system to haul a big load on the first day on El Cap. Keep in mind Mark weighs about 130 pounds, but look at the great rhythm he has with the pull.

The brake knot for 2 person glacier travel

The brake knot, designed to add increased friction in the event of a crevasse fall, is the best choice for traveling as a two person team on a glacier.

For glacier travel, many experts feel that four is an optimum number on a rope team, with three slightly more risky. If you choose to travel as a two person team, each climber needs to be highly skilled in crevasse avoidance, crevasse rescue, and have all the necessary gear.

A two person team is harder, because stopping the fall and then trying to build an anchor with the weight of your fallen partner on your harness is a significant challenge.

Studies by ENSA (École Nationale de Ski et d'Alpinisme) or French National Mountain Guide School, determined determined that a few bulky brake knots in the rope between a two person team can significantly help with crevasse rescue, assuming fairly typical snow conditions on the surface - not completely bare, and not too loose and fluffy. The knots typically shorten the length of a fall, and make it easier for the person on top to hold the victim.

(On the flipside, the knots can complicate prusiking up the rope and rigging a mechanical advantage system, but the benefits of a shorter and easier to catch fall generally outweigh these shortcomings.)

The short version from ENSA:

“Our tests validated the effectiveness of this technique, and we strongly recommend climbers use it.”

IMAGE: HTTPS://WWW.YOUTUBE.COM/WATCH?V=QHW9AM7AHLA

While a standard figure 8 on a bight loop or butterfly knot is effective, ENSA suggests using a “brake knot”. It creates a larger diameter, more spherical-shaped knot that offers more friction against the snow.

Here’s the method they recommend to tie the knot. Fortunately, it's a simple modification of the figure 8 on a bight, so it should be easy to learn and remember for pretty much anyone.

Tip - Don't make the loops too large, because this is just wasting rope.

Each brake knot takes about 1 meter of rope, so take this into account when setting your rope spacing. Tie the knots first, and then measure your 7-8 or so arm spans between climbers.

Start with a standard figure 8 on a bight, with a loop of about 1 foot.

Next, tuck the loop around the knot . . .

and finally, pass the loop back through the knot, then snug down each strand to dress it. The final loop created should be just a few inches tall.

The knot tying instructions starts at 6:20 In the video below, hopefully this link should take you right there.

And here's a nice video from Ortovox featuring some pro German guides who have much the same conclusion. It works!