Alpine Tips

How to 1:1 haul a load that’s heavier than you

A 1:1 haul is the big wall standard for moving up your vertical camping supplies. But when it starts to be close (or even a bit more) than your bodyweight, it can be very hard to lift. Here’s a #CraftyRopeTrick that let’s you haul extra-heavy bags 1:1.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

The standard way to haul on a big wall, with moderate loads, is a 1:1 haul with a redirect on the anchor.

By standing in a sling or aid ladder attached to the haul strand, you use your bodyweight to lift the load, rather than pulling up with your arm muscles, always a good thing!

Step down in the sling, and the load moves up. Slide the ascender up, repeat about 100 times, and your pig is at the anchor.

It looks something like this:

Let's say you rig your haul system with a highly efficient progress capture pulley on the anchor (such as a Petzl Traxion). If you apply your bodyweight to the pulling side of the rope, AND your bodyweight is greater than both the load and the slight added friction from the pulley, the load should lift.

For example, if you weigh 75 kg / 165 lbs, and you have a haul bag that weighs 50 kg / 110 lbs, simply applying your bodyweight by stepping onto the pull strand should lift your load.

So far so good. But . . .

What if your haul rope runs over rock between you and the load, adding additional friction?

What if your load is more like 60+ kg instead of 50 kg?

Now, simply standing with your static bodyweight on the haul strand may not be enough to lift the load.

If this happens, many climbers think . . .

They need to resort to a more complicated 2:1 hauling system.

Or do something more physically extreme, (photo below) or have your partner also attach to the rope to do a tandem haul, or something like that.

Guess what? There’s a clever trick to still use a 1:1 hauling system, even when the load you're lifting might be greater than your bodyweight.

There are two components.

Lifting UP on the load strand with one hand. (To be clear, you're not trying to lift the entire haul bag with one arm; just giving it a little bit of pull so you can lighten the load enough to move the load by pushing down with your foot on the other side.)

Bouncing / shock loading the hauling strand with your foot.

When you do these two things simultaneously, it both slightly reduces the load on the anchor AND multiplies your bodyweight on the haul side, letting you lift a load that weighs more than you do. Cool!

Want to see a video of this technique on El Capitan?

How about an example of the wrong way to 1:1 haul a big load?

Join my Premium Membership to read the rest of the article.

Thanks for your support!

Adjustable tether + Fifi hook for tricky cleaning

Here’s a DIY gear trick that’s handy when cleaning a traversing aid pitch, or maybe a overhanging sport route. Girth hitch an aid climbing fifi hook to an adjustable tether.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

Cleaning a steeply traversing aid pitch or a sport route that's severely overhanging and/or traversing can be hard!

The challenge you have in both cases is the gear you're trying to clean is being tensioned by the rope under your bodyweight, and that's usually a pretty big problem.

Here’s a simple way to solve it: an adjustable tether plus an aid climbing fifi hook.

I‘ve used this on the infamously traversing bolt ladder on Monkey Face at Smith Rock Oregon, and it works perfecto.

Be sure your fifi has a “release cord” loop tied into the top hole as we see here. This is key to be able to release this under load.

They usually don't come this way from the store, you have to add it yourself. I'm simply using parachute cord.

Notes . . .

It’s pretty much the same procedure for cleaning quickdraws from a steep sport climbing route, but that's a bit easier than this.

Yes, there are several methods you can use to accomplish this, but after you try this you may not wanna do the others. Give different techniques a try and see which works best for you.

What's sweet about this for aid climbing is that it uses gear that you already have on your harness. Typically you would only use a fifi when leading, but in this case, you remove it from your harness and put it on your tether when needed for cleaning.

Want to learn how this works, step by step?

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

Ascenders - when not to use the handle

Just because your ascender has a handle doesn't mean you have to use it. On lower angle rope climbing, the handle can be great. When it starts to get steep, you might want to try a more ergonomic hand position.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

This tip idea is from Australian rigging expert Richard Delaney. Connect with Richard on Instagram and his YouTube channel, where he has loads of concise, informative videos.

Just because there's a handle on your ascender doesn't mean you have to use it.

Handles can be great on lower angled rock, but if things get vertical, it might be more ergonomic or comfortable to put your hand on top of the ascender. Squeeze and lift the top to slide it up, and sort of press down on the sides and top as you stand up.

Keeping your hand off of the handle can serve as a subtle reminder that you shouldn’t be trying to do one arm pull ups. Use your legs to push up, and your arms mostly for balance.

Big wall climbers will usually use handled ascenders, because they are alternating between low angle and steeper rock. Rope access people may choose to avoid handled ascenders, or use them in the way shown here.

Want to learn a few more ascender tips?

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

30+ tips for more efficient aid climbing

A summary of various tricks and tips to aid climb more efficiently, also known as “just about everything I wish I knew when I started aid climbing”. These tips may take years off your learning curve.

Premium Members can read the entire article here:

Nearing the top of Moonlight buttress in a day, Zion National Park, Utah. Photo by me

“Speed climbing” on a big wall route gets a lot of press. But in reality, most of us plodders would do better to focus not on speed, but rather efficiency. Efficiency can mean not running out of water when your three day climb turns into four, avoiding strangling your partner (or vice versa), not taking 30+ minutes for a belay changeover, not climbing by headlamp when you could be kicking back in your portaledge . . . you get the idea.

Below is a somewhat random assortment of climbing tips to help you climb with greater efficiency, and thus speed. Why do I mention these particular tips? Because I ignored pretty much every single one of them on my first couple of walls and sometimes went pretty darn slow as a result. Sure wish I knew all these beforehand!

If you’ve been at the big wall game for a while, you probably know most of these already. If you're fairly new to aid climbing, these tips may be more helpful. These are merely my opinion/experience, and are by no means a complete list. In no order of importance, here we go.

Don’t rush

Speed does not mean fast. Speed means smooth, controlled, well-planned, and properly executed. The Navy SEALS have a saying: ”Slow is smooth. Smooth is fast.” Do the task you have in front of you at a proper pace, and do it right the first time. “Smooth” comes from practice and having your systems dialed before you get up on a real climb.

What you're really striving for is efficiency, not speed. If you achieve efficiency, you can actually slow down in your movements, be more relaxed, and enjoy your experience more. Another way to think about it: you increase your speed by minimizing the downtime when no one is making upward progress.

Wall ace Mark Hudon: “Most wall climbers today would gain far, far more time by simply understanding and doing the basic big wall tasks faster.” So, what are the basic tasks? Leading, cleaning, hauling, anchor building, belay changeovers, rope / belay management, staying fed/watered and comfy during the day.

Think of everything physical as a “movement sandwich” (rest, move, rest)

Unlike most other aspects of rock climbing, you can rest pretty much whenever you want to on a big wall. Use this to your advantage. From big wall expert Andy Kirkpatrick’s excellent aid climbing book, “Higher Education”:

“You should never find aid climbing hard. If you do, it means you're doing it wrong. If your arms are tired when leading, you're not resting on your fifi hook. If you get pumped ascending a rope, that means your lanyards are not set right or you’re standing in the wrong step of your aider. The same goes for hauling, if you're busting a gut then switch it up to a 2:1 or maybe space hauling. Almost everything physical should be a ‘movement sandwich’, movement placed between two slices of rest. Rest-move-rest. Rest-move-rest.”

Time yourself when practicing

Yes, we’re talking stopwatch. During your training, time yourself and your partner doing different tasks. How long did it take you to do EACH of these tasks - Lead the pitch, build the anchor, fix the rope, set up the haul, do the haul, clean the pitch, re-rack the gear, and have your partner start leading the next pitch? Repeat all these on the same training route different times maybe over different days, and notice your times hopefully start to dramatically improve. Have fun, and make training a little competitive. Time each segment, loser buys beverages.

Don’t “learn” to aid on a real route

People stuck behind you who have the skills to climb it for real will NOT be happy. EVERYTHING you do on a wall should be practiced BEFORE you get to the actual climb. To put it another way, on your actual route, you should never be trying something for the first time.

Do repeat laps on obscure 5.11 cracks until you get your movement and systems dialed. Time yourself.

Haul practice: start with a moderate load of around 50 pounds until you get your systems dialed. Then start ramping up the weight.

Haul a 100 pound bag 1:1.

Experience “riding the pig” by rappelling with your fully loaded haul bag. ( Tip - don’t hang it from your belay loop!)

Set up your ledge on a real cliff and spend a night in it, not just in a backyard tree.

Poop in a bag, on your ledge

Do “aid bouldering” close to the ground, placing all manner of tiny stoppers, marginal hooks and micro cams until you really know how far you can push them before failure.

Practice passing a knot, both going up with ascenders and going down (rappelling).

Put in your training. Practice the core skills. You, your partner, and everyone behind you on the route will have a much better time. (People who go try Monkey Face at Smith Rock Oregon who have never aid climbed before and take 2 hours to lead and clean a short bolt ladder, I’m looking at YOU!)

You can practice just about every big wall skill on a short route

When practicing, make the best use of what you have. This could be a route in a cooperative climbing gym, or a one pitch obscure crack at your local crag. Don't start the pitch standing on the ground. Climb up just a few meters, make a hanging belay, and start from there. Make a few moves, build another belay, haul and bring your partner up and repeat. This gives you extra practice at anchor building, hauling, and transitions, which can be a giant time suck for beginners.

Have all the skills needed for your route

Study the topo, photos and trip reports. Is there a pendulum and a lower out? How far is it? Do you need to hook? Is there a burly off width? Do you know how to clean a traverse? What’s the hardest mandatory free climbing, and can I/we do it?

Do you know how to lead AND clean a roof? The classic “Kor Roof” pitch on the South Face of Washington Column in Yosemite has shut down many an ambitious first time big wall team. Roof climbing is admittedly hard to practice, but read the topo and do your best to train before you go. Try the underside of an outdoor staircase, playground swing set, rope between 2 trees, or roof route in a helpful climbing gym. If you’re in Yosemite, be sure to put in a practice lap or two on the LeConte Boulder.

There’s a bounty of route beta for just about every beginner route you would ever want to try. Study up, know what skills you need to have, and master them before you go.

Talk over each pitch before the climb

Before you leave the ground, go over every pitch in detail with your partner. Talk over who’s going to do what, when will it happen, and how you’re going to handle any anticipated difficulties. Do we have all the gear needed for the route? What’s the farthest we need to lower out the bags, and do we need a separate lower out line? Does a pitch go around a corner so we maybe can’t hear or see each other? (Better have a clear communication plan.) Are we leading in blocks or swapping leads? Who gets what pitches? What’s our anticipated timeline, and what do we do if we’re faster or slower than we planned?

Having an action plan means you don’t need to create one on the fly and make important decisions when you’re tired and stressed. Sure, you can change your plan, but it’s a starting blueprint that guides your actions, instead of pretty much winging it on every pitch.

Route topos

Make several copies of the route topo. One for each person on the team and one extra. I like to laminate mine at the office store, and put in a grommet, and then tie some cord through the grommet as a clip in point.

Save a photo or PDF of the topo (and other relevant beta, like the descent route) onto your phone, which is free and weighs 0.0 grams. This goes for your partner as well.

Always ask yourself when you have downtime: “What could I be doing right now to make this climb faster or safer?”

Especially for beginners, there’s almost always something. Be on a constant lookout for small potential problems, and deal with them before they become larger real problems. “Hmm, looks like that haul rope is hung up on something. I better deal with that right now before the leader starts to pull it up . . . ”

Andy Kirkpatrick: Remember the number one sentence that needs to be avoided on a wall: “Hang on a minute!”

Strive for well-organized anchors

This is probably the single biggest time suck and cluster-generator for newer climbers. Something as simple as which side of the anchor to dock the haul bag can create either an effortless release or an incredible tangle. Decide where the bag is going to go, use rope bags, have multiple full strength clipping points, keep the lead rope and haul rope separated and tangle free and you'll be well on your way.

Maintaining the psyche

Big wall expert Mark Hudon has some self-talk he uses when things get spicy: “I may be scared, but I’m at LEAST as good as the WORST climber who has ever done this route! If they got past this point, dammit, so can I!” Remind yourself of this, and maybe even laugh a little when you’re faced with a tough spot.

Be patient with your partner and do not “blame”, no matter whose fault something might be. Mistakes will happen. Work together to overcome the problem.

Use a day bag

Don’t be diving into the haul bags at each belay to get snacks, water, sunscreen, windbreaker, etc. It's big time suck, waste of energy, and greatly increases the chance of dropping something. In the morning, put all the stuff you need for the day in a smaller “day bag” (aka “piglet”) or wall bucket, tied outside your haul bag (probably on a gear tether) for easy access. (Remind your partner to get their day gear all ready at the morning bivy.) Check out the “RTFN bag” and Wall Bucket at Skot’s Wall Gear.

Second leaves the belay fast

Try to minimize time when both climbers are at a belay and not moving. Especially, strive for fast belay changeovers. Slow belay changeovers can be a huge time suck for beginners.

The leader should call down when they are getting close to the anchor (the 25 foot rule) so the second can start tidying things up. One good thing for the belayer to do at this point is to be sure the haul bags are properly packed away, unencumbered, the haul rope is running freely, and the bags and rope are ready for lift off, because the very first task for the leader is to pull the bags a little bit off of the anchor, so the second can clean everything.

The leader should never be “ready to haul” and have to then wait for the second to sort things out!fdecide

When the leader calls “rope is fixed” the second can clip their ascenders to the lead rope and fully weight it. This frees up most of the anchor, the second can get to work breaking it down, and get ready to release the bags.

Releasing the bags should be pretty much effortless if you use a docking cord, which is a tether that’s releasable under load. Forget the old school method of using a daisy chain or some other static sling to connect your bags to the anchor; this can often require brute force to get your bags moving, especially if the pitch above traverses.

If the next pitch traverses to one side (say the right), you probably want the bags docked on the right side of the anchor, so they don't swing across you and smack you when you release them.

There's really no need to haul the bags up snug with the anchor on every pitch, unless you’re spending the night there. Hanging the bags a bit below the anchor can make your belay less clustered.

Generally, the bags should never be undocked by the second until they have fully lifted off from the anchor, and the second can check that nothing is hung up, carabiner is being weighted correctly, etc.

Clean the gear in semi-tidiness

You don’t need to be super type A and organize every piece of gear immaculately when cleaning, but you also don’t want to clip it any which way.

A cleaning system that works well: have two single length / 60 cm runners, one over each shoulder. Use wider nylon slings rather then skinny Dyneema - wider is more comfortable under a load of gear.

Clip free carabiners and slings onto one runner, and gear onto the other. Generally order the gear by size, but don’t be too fussy about it at the expense of upward progress. Avoid racking gear on your waist loops, unless you like the feeling of 30+ pounds of hardware causing your harness to slowly creep down towards your ankles.

When the cleaner gets to the top anchor, these two gear slings get clipped somewhere safe, and quickly added back onto the lead rack by whoever is leading the next pitch.

Doing this allows you to quickly hand off the gear at the next belay, rather than unclipping things one by one from your gear loops. This is much faster, and there’s less chance to drop things.

Want to learn about 15 more big wall efficiency tips like this?

Join my Premium Membership to read the whole article.

Thanks for your support!

Passing a knot when hauling

Want to lead a few pitches on a big wall, and then do one long haul to bypass an intermediate anchor or two? Here's a crafty way to connect two or more ropes to do this, and easily get that knot through your hauling system.

Credit for this tip goes to Andy Kirkpatrick. It’s from his outstanding book: ”Higher Education: A Big Wall Manual”.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

This might be a seldom-used technique in your toolbox of big wall trickery, but it can sure come in handy for one main thing: it lets you do extremely long hauls, with two or more ropes tied together, allowing you to skip intermediate anchors. For example, you could lead several pitches and then do one L O N G haul.

What’s the problem you need to solve? You have two ropes tied together with a knot that can’t pass through your progress capture pulley / Traxion. This means the knot (which is under a lot of tension) needs to be untied somehow without losing your haul bags.

(Note, if you're hauling with a 2:1 “pig rig”, passing a knot is really easy, because you already have about half the system in place. For this example, we’ll assume a 1:1 haul.)

There are several ways to accomplish this. Here's one that's pretty straightforward. Credit for this technique goes to Andy Kirkpatrick and his excellent big wall book “Higher Education”, definitely recommended.

Before we get into the technique, here’s a favorite related quote from Andy K:

“Hauling is potentially one of the most dangerous aspects of big wall climbing. This translates to ultra-caution in all parts of your hauling system and interaction with bags, haul lines, docking cords, and pulleys. If you rush and make a mistake, drop a load or have it shift where it's not wanted, you could easily kill someone or yourself. I try and teach climbers to view their bags as dangerous creatures, like a great white shark, rhino, or raptor that is in their charge. The ability to keep them calm and under your control comes down to paranoia, foresight, and heavy respect for the damage they can do.”

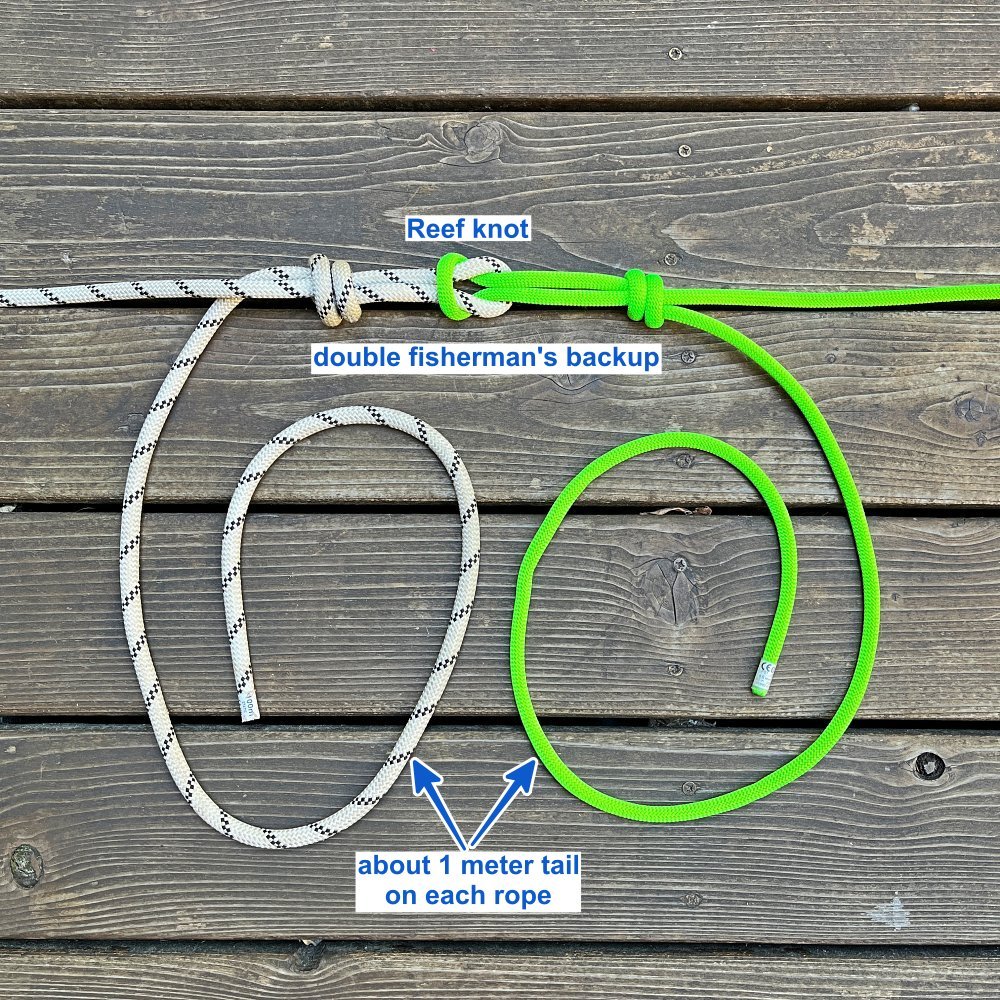

First, you need to join the ropes with a knot that won’t get welded under a heavy load, perhaps multiple haul bags. Try using the reef knot, backed up with a double fisherman’s, and a long tail of about 1 meter, as shown. There are certainly other options. This one is simple, easy to check, and works well.

It's critical here to leave a minimum of 1 meter tail on the ropes, as shown. (You actually only need it on one strand. But, so you don't screw it up, it’s simpler to make a long tail on both strands.) If you're not sure if you have enough tail, make it a bit longer.

We’re hauling on the white rope. Stop when the joining knot gets about 10 cm / 4 inches from your progress capture pulley. Don’t yank the knot into the pulley!

Get out some more gear: two lockers, a 30 cm (or so) sling, and an ascender. (Instead of the ascender, you could also use a friction hitch, but make it a good one.)

Clip the ascender upside down to the loaded rope. Clip the other end of the sling to the anchor. Here we’re using the Grivel Vlad on the master point, a combination locking carabiner and rigging plate, very helpful for this procedure. A quad, or other type of anchor rigging that gives you several different connection points, works too.

Next, pull up a bit on the white rope, release the cam on the Traxion, and slowly transfer the load onto the ascender. Once you do this, re-engage the cam on the Traxion to back up the ascender.

Notice how doing this creates slack on the knot, yay!

Safety step: tie a bight knot in the end of the green rope and clip it to the anchor with a locker. This ensures the ascender is backed up before you do the next step.

Sweet, you have slack on the knot, and the system is backed up. Now you can untie that reef knot that was joining the ropes. (Give yourself a high-five because you picked a knot that was so easy to untie. =^) Remove the white rope from the system; careful, don't drop it!

Carefully remove Traxion from the carabiner, load the green rope into the Traxion, and untie the backup bight knot. If you feel lucky and are comfortable with the ascender holding the entire load for about two seconds, you can keep the Traxion clipped onto the anchor and push the end of the green rope through the device. I'm showing a bit more conservative, less risky method.

Remove the ascender and sling from the system.

Schweeeeetness, Give yourself a high five, you're done!

All the load is now on the green rope with no knot. Now all you have is 60 more meters of hauling, lucky you!

Rack spare carabiners in a "football"

Big wall climbers need a LOT of spare carabiners. Here's a good way to keep them tidy - rack seven of ‘em together. (Like the 7 points for a touchdown in ‘Merican football, eh?)

I think I first heard of this tip from big wall ace Pete Zabrok. Pete wrote a great book on big wall climbing called Hooking Up, highly recommended!

Here's one way to help tame the entropy of your big wall gear harness.

Aid climbers need a LOT of free carabiners. Here's one good way to carry them.

Rack seven carabiners together. One to your gear loop, and then three more pairs hanging below that. This keeps them fairly compact and tidy. Seven, like the points for a touchdown in American football, eh?

Are you concerned that your fumbly fingers might accidentally unclip the top carabiner and then you lose all seven? An Instagram friend suggested racking 6 carabiners / 3 pairs, and making the top two opposite and opposed. This makes it less likely that he might accidentally unclip the whole thing. I think this is a pretty clever idea. So there you go, do it with six or seven, your choice!

Big wall water tips

For big wall climbing, water is the heaviest, and arguably most important, thing you can bring. Here are some solid tips for how much to bring, the best type of bottle, little-known material for a keeper cord, the frugal climber’s electrolyte mix, and even how to make a mini fridge in your haul bag.

Water on a big wall: How much to bring, and how best to store it?

It's the heaviest thing in your haul bag, so you don’t wanna take too much, but you definitely don’t want to run out either.

Good rule of thumb for quantity: 3-4 liters per person per day. You typically drink more lower down where it's warmer and the loads are heavier and less as you get higher up.

Start with sturdy bottles, with a secure lid, and a flared “collar” on top. The time-tested two liter pop bottle is a good choice for most of your water; plus, the round 2 liter bottles fit your round haul bag better. Bottles designed to hold carbonation are usually built stronger than a standard drinking water bottle. The collar, that’s just below the bottom of the cap, gives a secure place for your keeper cord. Bring some smaller one liter bottles to fill in gaps at the bottom of your bag. One liter bottles from Aquafina, holding non-carbonated water, are excellent.

Some people have luck with 1 gallon Crystal Geyser bottles, but I've had those leak on me. I prefer one and two liter pop bottles.

You do NOT need to put duct tape on the entire bottle, or use a “full-strength” sling.

Don't take a lousy, thin bottle, and try to reinforce it with tape. It's better to take an already solid drink bottle and don't use any tape on it.

Everything needs a clip in loop on a wall, including water bottles. While 3 mm cord is popular, I prefer thick twine called bank line. It’s super strong (300+ pounds!) inexpensive, and holds knots very well, see photo. I use about 24 inches of bank line per bottle. Tie one for every bottle; bank line is cheap.

Make sure your clip in loops are solid! If a loop fails the bottle will fall, and could seriously hurt or even kill someone. Use a constrictor hitch, which is similar to a clove, but more secure. (Check out the video at the bottom of the page to learn how to tie it, very cool knot.) Make sure that knot stays solid with a couple of wraps of hockey tape. Tie the string ends together with an overhand, good to go.

Speaking of hockey tape, it’s great! Think of it as heavy-duty athletic tape, that has superb stick-ability even when cold, wet, sweaty, etc. A few wraps of hockey tape around the neck of the bottle secures the clip-in loop. Taping your knot is fast and cheap insurance. Just don’t waste your time and tape covering the entire bottle. Bring a roll of hockey tape with you on the wall, it’s helpful for other things.

Water jugs to avoid . . .

Do NOT use those 1 gallon jugs with a built-in handle as shown below. The handle looks tempting, but the tops suck and will come off. You absolutely want something that has a solid threaded top.

Some people like the 1 gallon Crystal Geyser bottles, but the plastic is flimsy and I've had them puncture on me. The plastic in carbonated pop bottles is much stronger.

A few other tips . . .

Water for the leader . . . There's basically three options: carry some, don't carry any, or haul some up later on a tag line. If it's not too hot and you're moving pretty fast, have a drink before you start your pitch and hopefully you won't need much more. If you do need water on your lead, you're already carrying a huge load of gear so don't take a bigger bottle than you need to. Have a small bottle, like 1 liter max, for the leader. If you're using a tagline to bring up more gear or anchor materials, you can use this to bring up water mid-pitch.

Remove any labels from your bottles, and that little plastic ring around the neck, which can sometimes interfere with tying your clip in loop.

On day one, if you drink a lot of water before you leave the ground, you might be able to start with slightly less, like .75 gallons.

Try to really squeeze the full bottles into the bottom of your haul bag. Doing this fully spreads out the sides of the bag, making it lots easier to pack the rest of your stuff.

An insulated wide-neck Thermos bottle lets you keep real ice cubes for a day or so, which can be very handy for that well-earned end-of-the-day beverage. Totally optional, but nice.

If it's hot, an umbrella for shade and a plant mister bottle to spray yourself off at the belay can help you stay cool and drink less.

A few squeezes of lime or lemon juice can help cut the big wall cottonmouth. No need to be gourmet here, the little plastic bottles of citrus juice from the grocery store work fine. A big squeeze of lime/lemon juice, a few sugar cubes, and some salt is the Frugal Climber’s sports drink.

If you have access to a freezer, freeze most of your water bottles if it’s going to be hot. Having ice cold water on a multi-day hot weather big wall is priceless. Don’t freeze everything solid or you’ll be thirsty on day 1. Freeze some bottles all the way for the latter part of your climb and some other bottles halfway for the first day. Don't fill them all the way to the top before you put them in the freezer or they will probably crack, duh. Be sure and top off all frozen bottles with liquid water before you start (it's easy to forget to do this, ask me how I know.)

If you have a preferred powdered electrolyte/sport drink mix, add this to the bottles on on the ground, especially if you’re going to freeze your water.

Tip I learned from hownot2.com and the Big Wall Bible (haven't tried this but it sounds brilliant): if you're not taking a ridiculous amount of water, you can put frozen bottles around the perimeter of your haul bag, which will leave a small area on the bottom in the middle that is essentially a refrigerator. You can use this to keep perishable food cold, like something really yummy you can eat on the first night.

Remember to pull out enough water for the day each morning and keep it accessible in your day bag or wall bucket. You don't want to be diving into the bottom of your pigs during the day to replenish water, or for any other reason, for that matter.

If you’re bailing, don’t pour out or bring down your water. Leave it for someone else if you can. (You might wanna check local land management regulations to see if this is okay,) If you have some way to leave a message, write “Free” on a note or tape and leave it on the bottles. Make sure it’s well secured and not going to roll off the ledge, that could be a big hazard to someone below if it falls off.

Reuse your bottles. When they're empty step on them till they squish flat, and then screw on the lid. To re-inflate for the next wall blow them up by lung power, seal the lid and then gently roll them around. The dented parts should expand. (At the very least, offer them to somebody else at Camp 4.)

Here’s a nice short video on how to tie the constrictor hitch. This is perfect for attaching a keeper cord to water bottles. Sometimes embedded Instagram videos like this don't work. If you can't see this, go to the original Instagram link.

The far end haul, explained

The far end haul is a #CraftyRopeTrick that sets up a redirected 2:1 mechanical advantage haul that happens at the load end of the rope, not at the anchor end of the rope. The far end haul is used in big wall climbing, and can be handy for self rescue. Plus, it's just plain fun to set up to see how it works!

The far end haul haul for big wall applications is generally attributed to Chongo, a legendary Yosemite dirtbag who was famous for extended vertical camping trips on El Capitan with ridiculously large loads.

Having a Petzl Traxion (or similar progress capture pulley) on the load also lets you set up what’s called a “far end haul”, which at first seems like some sort of sorcery. (This load can be you, or another person pack, haul bag etc.)

Usually, hauling happens from the top end of the rope next to the anchor. However, with the far end haul, you to lift your load with a theoretical 2:1 mechanical advantage (MA) by pulling on the “far end” of the rope next to the load, rather than from the primary anchor.

This rig can be useful for big wall soloing / hauling. If you’re hauling your bag from the top, and it gets stuck, you can rap down to it, lift up a little bit by setting up a 2:1 MA with an ascender and a pulley, and free the bags.

I learned from a caver that this is also called a “traveling haul”, used in rescue to raise someone up a large drop. (Hope I never have to do that!)

It also has some self-rescue applications, and can be really helpful for moving your bags around at the anchor, see video below.

To rig the far end 2:1, clip an ascender (or a prusik if you’re short on gear) on the loaded strand of the haul rope, clip a carabiner with a pulley onto the ascender, and pull down on this redirect. Your bodyweight should lift the bags with this theoretical 2:1 MA and the micro traxion will “climb” up the rope and capture your pulling progress, sweet!

In the photo below I'm using a handled ascender. You could use any kind of ascender here like a Tibloc, a second Micro Traxion, Ropeman, etc. The pulley is optional, but definitely helps increase your efficiency when pulling.

Note the real mechanical advantage you will have in the real world when you try this. Below are pull test results with a 10 lb weight from another Alpinesavvy post, mechanical advantage in the real world. You can see that about the best you can do with the far end haul pulley is 1.3 to 1. And if you don’t have a pulley, you probably shouldn't even bother putting the redirect through a carabiner, as the mechanical advantage falls below 1:1. (Note, DMM Revolver carabiners don’t really do anything to reduce friction over a regular carabiner, avoid using those.)

But, even if you’re not soloing, it has a few advantages.

The far end haul can minimize rope abrasion, because the haul rope doesn’t move.

If you have to haul from a point or over a ledge with a LOT of rope friction, you can instead far end haul and have zero friction.

You can easily move the bags around at the anchor; more below.

Here’s a video by wall ace Mark Hudon who shows exactly how to do this. Rather ingenious, no?

Haul bag rigging 101

There are lots of different approaches for rigging your big wall haul bags. Some old school methods still work pretty well, but there are a few more modern approaches that might make things a lot easier.

Thanks to big wall ace Quinn Hatfield @sprint_chef for the “connect two bags with quick links” tip near the bottom of this page.

A few words on hauling, from big wall expert Andy Kirkpatrick:

“Hauling is potentially one of the most dangerous aspects of big wall climbing. This translates to ultra-caution in all parts of your hauling system and interaction with bags, haul lines, docking cords, and pulleys. If you rush and make a mistake, drop a load or have it shift where it's not wanted, you could easily kill someone or yourself. I try and teach climbers to view their bags as dangerous creatures, like a great white shark, rhino, or raptor that is in their charge. The ability to keep them calm and under your control comes down to paranoia, foresight, and heavy respect for the damage they can do.”

There are MANY different ways to set up your bags for hauling. While some traditional methods have served big wall climbers fairly well for a long time, there are some more modern approaches that may make your life a lot easier. Try these different systems, and see what works well for you!

A more traditional / old school hauling setup looks something like this:

Cut off plastic bottle as a knot protector (lifted up here for the photo, in practice you slide the bottle down over the knot)

No swivel

End of haul rope tied directly to master hauling carabiner

Carabiner connects the short strap to the master point carabiner

Bag clipped to anchor with a sewn pocket daisy chain

old school haul setup

Let's look at a few potential issues with this set up.

Nothing really wrong with the plastic bottle. (Sidenote, big wall expert Andy Kirkpatrick suggests using an oil funnel from a car parts store instead of a plastic bottle. The oil funnel has a long, tapered neck that can allow it to slide past obstructions more easily. I haven't tried it but it sounds sensible.)

No swivel. A swivel is somewhat optional and costs a bit, but can definitely save your bags from twisting your rope.

End of rope tied directly to master carabiner. Again, nothing really wrong with this, but if you need to lower out your bags you're going to need an entirely separate rope to do so.

That red carabiner connecting the short haul bag strap to the master carabiner? That can be a BIG hassle with a heavy bag when the master haul carabiner is loaded, because you have to pretty much lift the weight of the bag and have one hand free every time you want to clip or unclip. There are much better ways to attach these two straps.

Finally, that evil sewn pocket daisy chain! That sucker can be very difficult to unclip, especially if the pitch above is traversing. Much better practice is to use a releasable docking cord, more on that below.

Here’s a more modern way to rig your haul bag.

A progress capture pulley such as a Petzl Traxion is attached to the haul bag, not a bight knot. Yes, you haul directly from the pulley. No, it doesn't damage the rope. The pulley gives you a lot more flexibility. You can lift up on the bags with a 2:1 mechanical advantage to transfer them from one anchor point to another, you can use the extra haul rope as a lower out line, you can do a “far end haul” with a 2:1 mechanical advantage if needed, and you don’t need the inverted plastic bottle as a knot protector, because there’s no knot. This is a good place for a triple action carabiner. Yes, the Traxion is expensive.

A swivel goes between the Traxion pulley and the master carabiner. Way less twisting of your rope.

A cam strap connect the long strap and the short straps. This means you never have to lift the full weight of the bags to clip and unclip the carabiner. Clove hitch the cam strap (a 3 footer /1 meter) to the haul point carabiner so you can’t drop the strap. Good place for a triple action (or here, a Magnetron) HMS carabiner. (Side note on the cam strap: After I took this photo, I found out that skotswallgear now makes a very nice 3 foot long cam strap for exactly this purpose, and that's what I'd recommend. Check it out here, scroll to the bottom of his store to see it.

A docking cord attaches the bag to the anchor, not a daisy chain. The docking cord is typically a doubled length of 7 or 8mm cord (about 15 feet / 5 meters) that's attached to the long strap of your bag. With this you tie some sort of releasable hitch onto the anchor, and that holds the weight of your bag. You can release the bag when this hitch is fully loaded, which is a HUGE improvement over hanging your bag from a sling or daisy chain. (Attaching the docking cord to the long strap rather than the hauling carabiner means that when the bag is docked, everything else is slack).

Here's one more tip on where to tie your docking cord (which I unfortunately learned after I shot all these photos). Most haul bags have some sturdy sewn tabs around the opening. If your tie your docking cord to one of these tabs, and around one of the straps, this lets you dock the bag higher up on the anchor, which often makes accessing the bag more convenient.

Tip: Clip a bight knot to back up the Traxion ABOVE the swivel

Just below the Traxion, tie a backup knot (here a butterfly) and clip it with a locker to the carabiner attached to the Traxion. This backs up the Traxion, and gives you a knot you can use to lower out. You can loosely stack all the rest of the unused rope in the top of the bag, or let it hang free.

If the Traxion cam were to open up on some rock nubbin when you're hauling, this backup knot prevents you from losing your haul bag.

Note: It's important to clip this bight knot ABOVE the swivel, and not below it. If you clip the bight anywhere below the swivel, there's a good chance when your bag twists, all of your extra haul rope is going to get twisted around the bag also, no bueno.

Check out the photo below of the correct (left) and incorrect way (right) to do this.

What about two bags?

There are LOADS of different ways to rig two haul bags. The basic concepts (that’ve worked for me) are:

Most folks like the bags side-by-side, but some prefer a smaller bag hanging below the primary bag. Try both and see what works for you.

It’s good to be able to spread the bags laterally if you need to wrestle them around.

You don't want them hanging too far down, so you have to reach uncomfortably low from the anchor. (This is not so important during the day at intermediate anchors, more so at the bivy.)

All connection points need to be unquestionably strong.

You need to able to unclip and separate the bags from one another if needed.

A docking cord connects the bags to the anchor. You can have a separate docking cord on each bag (as we do here) or go with with one single docking cord from the master haul carabiner.

Here’s one way to set it up. From the top down:

Haul rope running through Traxion progress capture pulley, backup knot below traxion, knot clipped with a locker above the swivel

Triple action locking carabiner

Swivel

2 pairs of quick links in swivel. The quick links are unquestionably strong, and give a nice lateral spread to each bag at the belay. (Thanks to Quinn Hatfield for this quicklinks tip.)

HMS locking carabiner attached to long strap on each bag. (Feel free to tape the gates closed if you want to be 110% sure they’ll never open.)

Docking cord attached with quicklink to each bag

On left bag, a 3 foot long camstrap (red)

Here's a close-up:

Here's a fancier way to set it up, from big wall expert Skot’s Wall Gear. Here, Skot is using a pair of gold rappel rings along with a combination swivel and locking carabiner (appears to be the Director Swivel Boss) from DMM. This makes a more compact set up, with zero chance cross loading the rings.

EDIT - An Alpinesavvy reader told me that many swivels made by DMM have been recalled. Do a web search for “DMM swivel recall” for more info on this.

photo: @skotfromthedock, https://www.instagram.com/p/C2nmw-By0-3/

Other hardware for haulbag rigging . . .

There are cool swivels that allows you to open one side. This creates some interesting options; for example you could maybe cut up a PAS tether to get small sewn loops of Dyneema or maybe a pair of quickdraw dogbones, and use these instead of the quick links. I haven’t tried these but looks like they could work.

Here’s a photo: the Petzl Micro swivel and DMM Focus swivel.

Petzl makes a nifty product called the Ring Open. This is a rigging ring that you can open (with a tiny Allen screw, I think), letting you attach a fixed loop. I don't have one of these, but it could be a cool option for setting up your haul bag system.

Like I said at the start, there are many, many different ways to do this. Start with the basic principles, and find a system that works for you.

Director Swivel Boss from DMM. This is the carabiner shown Skot’s photo just above. With this, you can use inexpensive rappel rings instead of the more expensive Petzl Ring Open.

Note that this device may be subject to a DMM recall. Do a web search to find out if yours is potentially a problem.

The far end haul

Having a Traxion on the load also lets you set up what’s called a “far end haul”, which at first seems like some sort of sorcery. Here's a detailed article and a couple of how to videos on this technique.

Haul bag straps: connect ‘em with a cam strap

Big wall haul bags usually come with a long strap and a short strap. You haul from the long strap, and need to hoist up the short strap to level and close the bag. It's that hoisting up that's the hard part! Make this a lot easier - replace the traditional carabiner with a cam strap.

Big wall haul bags usually have a long strap and a short strap. The haul rope is connected to the long strap. The short strap is connected / clipped in some way to the long strap. In theory, this allows you to access your bag with all the weight hanging on the long strap, by unclipping the short strap.

The traditional way to do this is with a second carabiner, as shown on the left.

Looks nice in theory, but in reality this is often a serious hassle. If the weight of the bag is loading the master point carabiner, to clip and unclip that red carabiner on the short strap, you may need to hoist the entire weight of the bag, and have a hand free to work the carabiner. With a moderate bag this may not be a problem, but with a full load it can be very awkward and unnecessarily strenuous. Imagine doing this with a 100+ pound / 50+ kg bag, no thanks!

A better method is shown on the right, using a cam strap. Let’s learn how that works!

Instead of that pesky carabiner, use a cam strap to close your bag.

Get a 3 foot cam strap. You can get a two pack of 3 footers for about $15, here's a link for REI. (This is NOT an affiliate marketing link, I simply offer it for your convenience.) Or get a 4 foot and cut it to size.

Tie a clove hitch in the cam strap, and clip it to the haul point carabiner. The clove keeps the cam strap secure so you don’t drop it. Try to keep the buckle close to the carabiner.

Run the cam strap through the short haul bag strap, then back up through the cam buckle.

Now, simply pull down on the cam strap with your bodyweight. Nice, you've created a little 2:1 mechanical advantage. This hoists up the short strap and secures your bag, nice and level.

The cam strap is releasable under tension, making opening the bag just as easy. No more strenuous pig wrestling to unclip that short strap carabiner, schweeeet!

Sidenote: if you’re thoughtful about gear packing, you should hopefully not be diving in and out of your main haul bag during the day. In the morning, try to pull out everything you need for the day, and put it in a smaller day bag or a wall bucket that you use for things like snacks, water, sunscreen, wind shell, etc.

Here’s a more elegant way to do it, with this cool cam strap design from skotswallgear.com. Skot sews a small loop right next to the buckle, so you can clip it to the carabiner rather than using a clove hitch. Note that the strap then passes through the carabiner as shown on the left photo, and then down and through the lower bag strap. (At least that's how I think you're supposed to use it. :-)

Skot was nice enough to send me one for review, thanks!

Skot makes lots of well-crafted big wall gear, like the famous Alfifi, lightweight and easily adjustable tethers/daisys, rope bags, custom webbing for hooks, and more. Check out his website to see it all.

If you use a docking cord that’s tied to the long strap rather than clipped to the master point carabiner, this means that both straps should have no tension on them after the bag has been docked at the anchor. This allows easy access to your bag, regardless of what system you use to close the top. Lots more on docking cords at this article.

Finally, here's a short video showing how it works.

Try the "T-Step" to stand tall in your aiders

Getting into your second step on your aid ladder on steep terrain can be a strenuous and awkward hassle with the traditional fifi hook. Instead, try the “T-step” method to stand easily in your second step with no fifi.

Note: This method is generally attributed to Ron Olevsky, aka “Piton Ron”, a big wall pioneer who has put up many classic aid routes in Zion National Park. I think Ron’s technique is slightly different than the one shown here, but it's the same general idea.

When leading an aid pitch, it's generally most efficient to stand as high in your aid ladders as you can. (As they say, everything looks better from the next higher step.) But dang, especially on steep rock, it's not quite as easy as it sounds!

If you’re using a traditional fifi hook and trying to stand in your second aider step, on vertical or overhanging rock, you need to maintain a delicate yet strenuous balance of opposing forces.

Your feet are pressing DOWN in your aiders, and your upper body straining UP against the inverted fifi. This often makes your harness creep towards your ankles, not good.

If the fifi sling is even a bit too long, it puts your center of gravity farther out from the wall, which makes you have to maintain a lot more core tension to stand upright, and often the unwelcome sensation that you’re about to topple over backwards.

If you release tension on the fifi for a moment, it could just fall away from the placement that you're pulling against, which really makes things exciting.

Does that sound uncomfortable and not very fun? You’re correct!

When aiding in the traditional manner, this is about what it feels like when you're in the top or second ladder steps . (Drawing credit, from the amazingly talented Mike Clelland.)

image: Mike Clelland, Climbing magazine

Modern tools such as the Alfifi, which is basically a fifi hook welded onto an adjustable tether, can make this process a bit easier, but it still is generally pretty awkward. Overall, standing in your second step in steep terrain is not easy nor intuitive for most people.

Here’s an alternative, simple way to comfortably stand in the second step of your aiders, on vertical rock to overhanging rock, without any sort of a fifi, that eliminates just about all of these problems - the “T-step”.

The effectiveness of this has to do with a few variables such as your height, your shoe size, what kind of aider ladders you’re using, the steepness of the rock, etc. For me, using Yates or Aideer ladders, with a size 10 shoe, and standing about 5’ 9”, I can stand easily in the second step on vertical or slightly past vertical. Your mileage may vary, give it a try and see what it feels like.

Here's how to do it.

1 - Place some gear, clip a single aid ladder to the gear, and stand in the second step with either foot; for this example, your left. Remember to aid climb like you free climb; use your hands in the crack or rock features to step up; don’t just pull on your aiders or gear.

2 - Point the toes of the foot that's not standing in the ladder, here your right, 90° away from the foot that's standing in the ladder. Then, slide your right foot over your left foot. The arch of your right foot should be about over the toes of your left foot, making a shape like the letter “T”. (T-step, get it?) The aid ladder should be between your right calf and left shin. You might have to put your left knee against the wall for a moment and bend your left knee backwards for a moment to make room for your other foot to slide in. Doing this creates a sort of lever that keeps you from toppling over backwards.

3 - Now, you should be able to stand comfortably in your second step, largely being held in place by the muscle of your right calf. You do NOT need a fifi hook, your pelvis is in very close to the rock so you have a good center of gravity and better reach, and you should not feel any strain on your abdominal muscles. Overall, you should be fairly relaxed and comfortable. This is a bit tricky to describe in words, but once you try it you'll intuitively get it. It really feels like a bit of magic the first time you do it!

Doing this, I’m easily able to reach about 5 feet between gear placements.

Stand tall and gain a lot of reach, no tricky three-way balancing and messing with adjustable daisy chains or fifis, and you don't feel like you've done 100 sit ups after you finish leading a pitch. What's not to like?

It might sound odd reading about it, but give it a try. Once you learn how to do this you might get rid of that fifi hook for almost everything.

As with most things in climbing it's a better show than a tell. Watch the video above a few times to see how it works.

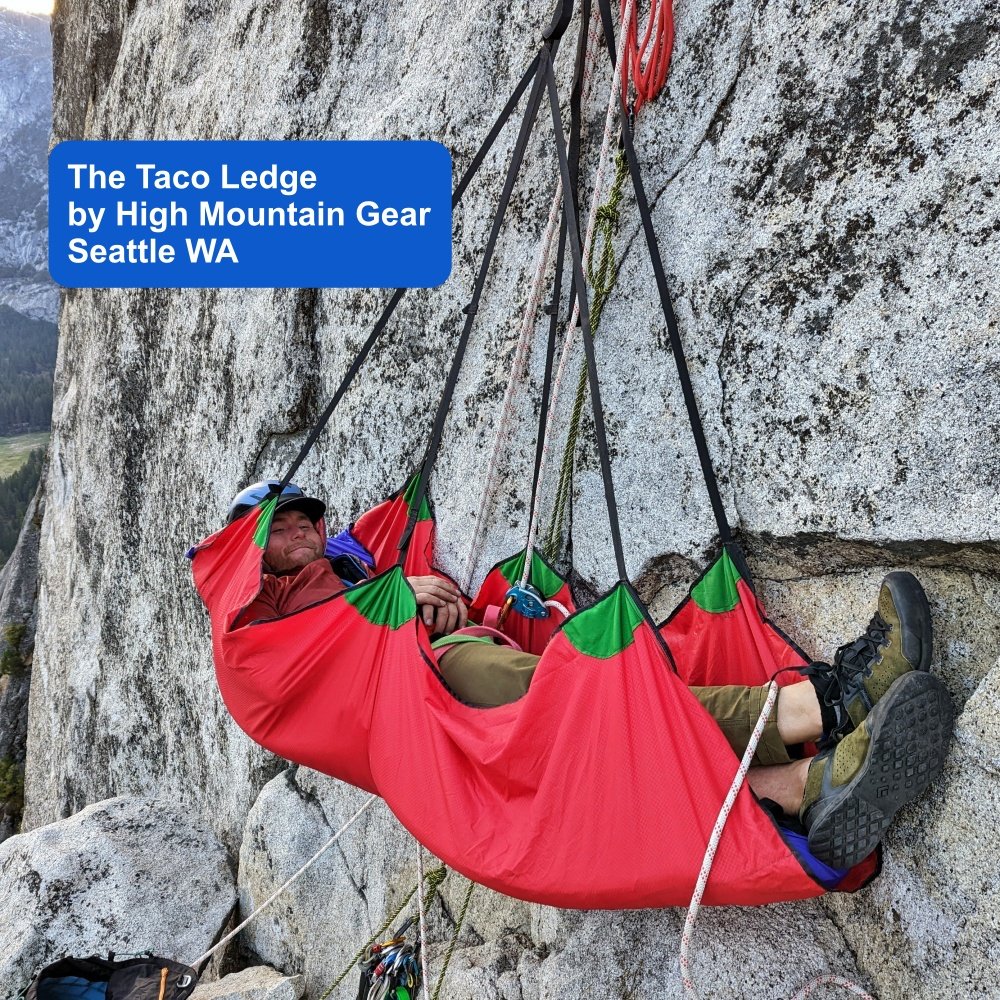

Cool new portaledge: the High Mountain Gear “Taco”

For a multi day big wall climb, you're probably going to need a portaledge. Here's an innovative new option which is lightweight, very compact, easy to set up, and quite inexpensive. Check out the High Mountain Gear Taco, handmade in Seattle WA.

Most photos, shared with permission, are from AMGA Certified Rock Guides Lani Chapko and Sam Boyce, theclimbingguides.com. Connect with them for guided trips and clinics, including big wall instruction. Instagram: @the_climbing_school, Lani: @goatsonropes, Sam: @chossdiaries

Alpinesavvy was provided with a free sample of the Taco ledge for review. This in no way affected my opinion and review. I only recommend stuff I think is great. Whenever I get a review product like this, I'll always tell you about it up front.

Want to get a Taco Ledge? Use the discount code ALPINESAVVY10 to get 10% off your order from High Mountain Gear.

This is not an affiliate marketing link and I do not financially benefit from this deal. I extend this discount as a perk for my readers.

There's no experience in climbing quite like sleeping in a portaledge. After a long day of upward struggle, inching up cracks the width of Donnie Trump’s pinky finger, wrestling both the haul bag and your mental demons, you’ve reached the bivy. Time to set up the ledge, kick back with bare feet and a well-earned tasty beverage, watch the afternoon light fade to evening, and hear the Doppler “swhoosh” of the swallows streaking by. It’s a sublime experience you’ll remember for a lifetime.

For big wall vertical camping, you’re going to probably need a portaledge. Yep, they are solid and comfortable, but you pay a high price in cost, weight, bulk, and (usually) set up hassle.

Here’s an intriguing alternative that addresses all of these issues: the Taco inflatable hammock. It’s made in Seattle by climber and sewing ace Kyle Willis and High Mountain Gear.

It’s a single point hammock matched with an inflatable sleeping pad. The pad adds a lot more rigidity and comfort than a plain hammock, creating a ledge that’s inexpensive, ridiculously lightweight, very compact, reasonably comfy, and super easy to set up.

Cost: $299

Weight: 1 lb 13 oz / 822 grams

Size: 76" x 49"

Packed size: without a pad it packs into a cylinder about 5" diameter by 10" tall (not much bigger than a Nalgene water bottle!)

Pad dimensions: 18"-26" wide and up to 78" long. (Pad is NOT included in the price.)

It’s an intriguing option for certain big wall applications where you want to minimize your load and save money to spend on . . . I dunno, maybe a few more Totem cams?

Now, if a weight under 1 kg is not already light enough for you, Kyle is working on a new model made from Dyneema fabric that comes in close to a ridiculous 1 pound for the ledge alone. Yes, this version will be more expensive, but if shaving grams is important to you, it’s an option.

You can rig the Taco not only as a horizontal ledge to sleep in, but also as a reclining lounge chair. If you're looking at a multi hour belay session, it's hard to get much more plush than this. The Taco is so compact and easy to set up, that you might even want to keep it in the day bag and use it at every belay as a chair, if you're doing long pitches.

One big advantage of the Taco ledge is the ease of setup and breakdown. As anyone who’s tried to set up a ledge in the dark and has been tempted to reach for the wall hammer to persuade that last aluminum bar into position knows, this is a significant benefit.

You insert your sleeping pad and adjust the straps that secure it on the ground before liftoff. The pad stays inserted for the whole climb. On the wall, setting it up is pretty much clipping the Taco to one good suspension point (it needs about 5 feet of hang) and inflating the pad. To break it down, simply open up the air valve, roll it up, fold the sides inward, and put it in a stuff sack. This literally takes just a few minutes.

The base model comes at a very reasonable price of $299 (pad not included) as I write this in Oct 2024. A couple of highly recommended add-ons are a zipper storage pocket (perfect for big wall beverages, headlamp, etc.) and a stuff sack.

Note that nothing on the Taco is rated to be a safety connection. Always stay clipped in with a real tether/rope to a real anchor. (A tip I learned from big wall expert Mark Hudon: take a completely separate short length of rope, about 6 meters of 8mm rope, just for tying yourself in and moving around the bivy.)

Learn more: Check out this in-depth article from theclimbingguides.com with several videos covering installing the pad, hanging the Taco, and setting it up in lounge chair mode.

Below: Taco time on El Capitan. Photo by big wall ace Kevin DeWeese, @failfalling

image: Kevin DeWeese, https://www.instagram.com/p/CdOQBL6rWUu/

Pro tip from Kevin: Twist a carabiner in one of the straps to shorten it a bit if you need to even out the ledge; see photo below.

FAQ . . .

What's the best application for the Taco? Probably longer routes that may have a fair amount of natural ledges, but you still need to spend a few nights out and want to travel light, have easier (or zero) hauling, and hopefully climb in predictable dry weather. Think the nose on El Capitan, NW Face of Half Dome, and classic routes in Zion like Prodigal Sun or Spaceshot. If you're planning a climb longer than a few days, or in questionable weather, you probably want to go with a more traditional portaledge with a dedicated rain fly.

Is it like the G7 Pod ledge? The G7 Pod is another innovative design. That ledge is fully inflatable with no metal frame. Like the Taco, the G7 is lightweight, compact, and is fast to set up. It also appears more durable, and has an optional rainfly. I’ve never tried it, but it looks plush and has great reviews. It’s also $685 (with a rainfly an additional $375). The Taco is $240.

Tell me about the pad. A proper pad, which is NOT included, is critical to the functioning of the Taco. Without a pad, it’s an uncomfortable single point hammock, like big wallers suffered with 40 years ago (see photo below). The optimal pad is 72 inches with horizontal baffles, like the Thermarest Uber Neo Air. Field testing shows a pad with a grid works okay, and a pad with vertical air baffles does not work very well, “taco-ing” your shoulders, which is what we’re trying to avoid. A pad that’s tapered toward the feet and is wider at the shoulders seems to work better than a rectangular pad.

Can I get a double? No. Get two Tacos and stack them vertically.

What about a rainfly? YES! Check out the Gordito rain fly from High Mountain Gear, made specifically for a Taco Ledge.

Schweeet! Where do I get one?

Use the discount code ALPINESAVVY10 to get 10% off!

The hammock concept on big walls has been around for a very long time. Check out this classic photo from 1964 with Tom Frost, Royal Robbins, and Yvon Chouinard on the FA of North America Wall, El Capitan. Nope, that is most definitely not a comfortable way to spend the night. Photo credit, Tom Frost

image: Tom Frost, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tom_Frost_-_Tenement_flat_-_1964.jpg

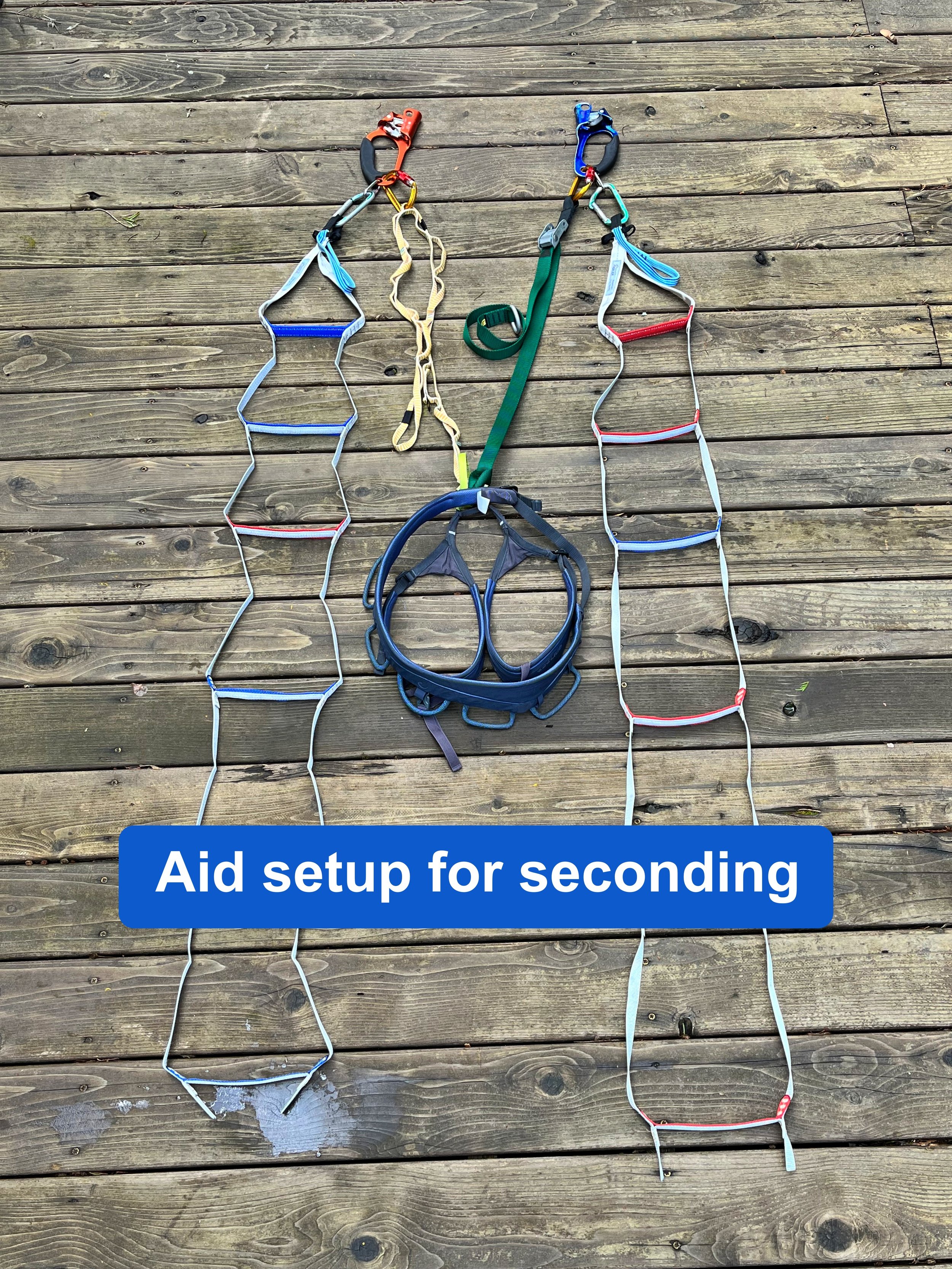

Aid climbing: rig for seconding

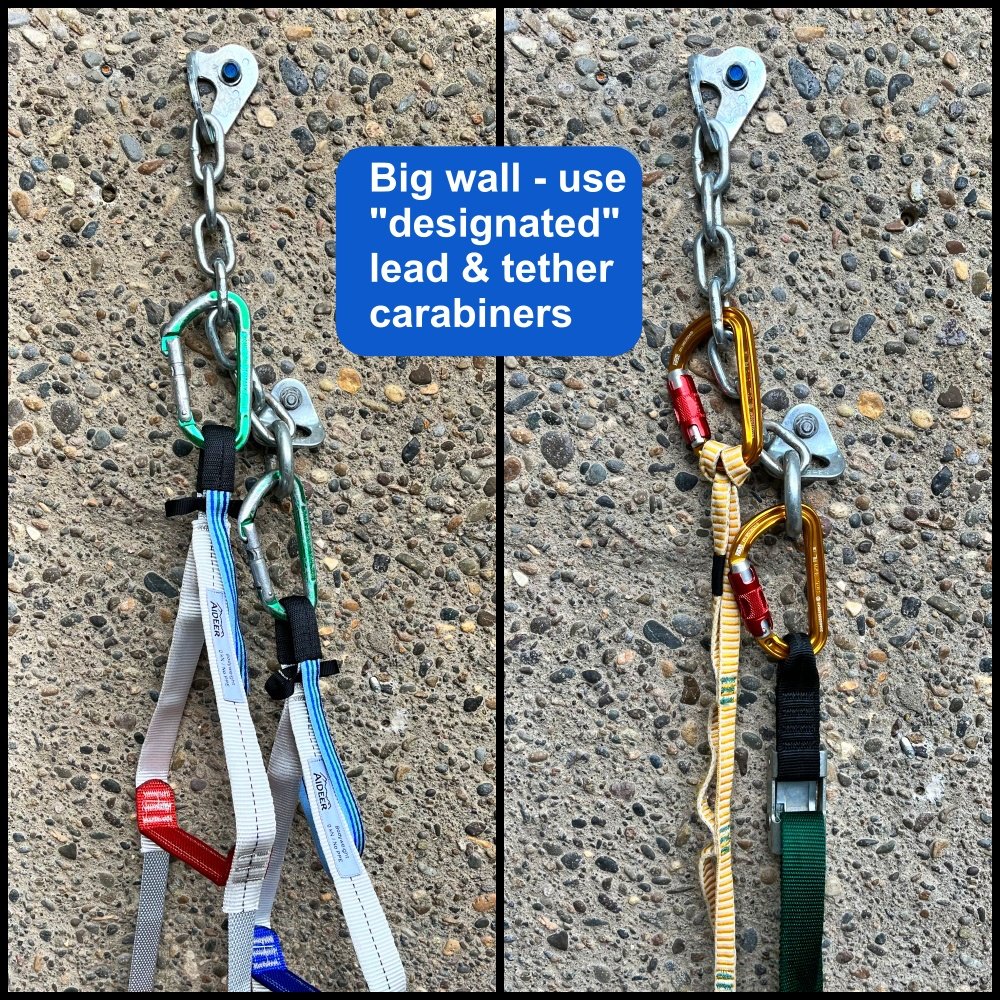

Having designated carabiners for your ladders and tethers, and having your tethers set to the correct length, is key to efficient ascending and cleaning on a big wall. Here's how to set it up, some specific gear recommendations, and pros and cons of alternative methods.

Having simple, repeatable, and easy to check systems for different components of aid climbing is critical. Your setup for seconding and cleaning is definitely in this category. When you're jugging thousands of vertical feet and and cleaning hundreds of placements, you really want to have this dialed.

Once you have it set up right:

Your tethers are set at the perfect length for efficient ascending

You use designated carabiners on your ladders and tethers, so you’re never patting down your harness looking for a spare carabiner

Transitions (between leading, clipping to anchors, hauling, and cleaning) are faster with minimal futzing around

First off, let's look at an ascender modification.

Most handled ascenders (except the newer Petzl ones) have two holes near the bottom, one large one small.

Add a small (5mm) stainless steel quicklink to the small hole. Crank it tight with pliers. Now you have a designated clipping point for your ladder, which goes on a snapgate carabiner. This not a mandatory mod, and many climbers do just fine without it, but I find it’s quite convenient. Here's an article with the whole scoop.

The main benefit to this is that it lets you more options to easily separate your ascender and ladder if you ever need to. Examples: Cleaning a traverse, when it might be convenient to clip the ladder to the next piece of gear and stand on it, to unweight the piece of gear you need to clean. Or, when you arrive at the anchor and you want to clip your tether directly to a bolt but you're still standing on the ladder, separation like this lets you do it.

Close up of the business end. The quicklink makes a convenient place to clip your ladder that's entirely separate from your tether.

Here’s how it looks on the rope.

Let's look at one good way to set up for cleaning. There are variations on this, but here’s what works for me. Experiment and see if it works for you too.

We’ll first look at the classic two ascenders and two ladders. This works best on lower angled rock up to about vertical, with the route not traversing too much. It does take a little practice so you don’t look like a marionette having a seizure.

There are other setups that can be more helpful if the rock is very steep, or if the pitch is traversing a bit. We’ll look at those at the bottom of the page.

Cleaning Tip: One simple way to keep things reasonably organized when you’re cleaning: get two 60 cm slings, and put one over each shoulder. Clip cams and wires to one side, clip slings and carabiners to the other. At the anchor, you can remove each sling, attach it to something solid and start re-racking on the larger, more comfy primary leading gear harness.

The whole shebang:

Tethers are girth hitched to the tie in points of your harness. The belay loop is fine as well

Both tethers are set at the correct length for efficient jumaring (more on that below)

Designated lead/ladder carabiner is clipped to the quicklink

Designated tether carabiner is clipped to the large hole on the ascender. Locker is mandatory

Ready to clean!

Tether length for seconding

When leading, you have your tether at full extension, because you need to reach high. However, when seconding, it’s critical that the tethers be shortened up to the correct length. If your tether is too short, you’ll make short, choppy, inefficient movements up the rope. If your tether is too long, you can’t reach the handle of the ascender from the rest position, and you’ll have to do some ab-busting contortions to reach it. Here’s an article on how to rig that correctly.

There’s a sweet spot in the middle, and here’s how to find it: With your tether girth hitched to your harness, clip the carabiner and an ascender to the end. Pull on the adjusting strap (or clip a daisy pocket) until the bottom of the ascender carabiner is at your eyebrows. Most people find this to be just about the perfect length.

Set this same length on BOTH tethers - I long thought that you only needed to adjust the length of your top / upper tether, typically your dominant hand (for me the right). However, big wall expert Mark Hudon convinced me otherwise. Mark’s reasoning: while the bottom tether length doesn’t matter if your pitch is straight up or leaning to the right, what about when the pitch traverses to the left? In that case, it’s usually easier to lead with your left ascender, in which case the left tether needs to be the correct length also. So, Mark‘s point is to set both tethers to the same correct length, and you’re good to go in any situation.

Once you get this length dialed, mark the it on your tethers with tape or Sharpie pen so you can set it correctly first time. I like hockey tape for the sewn loop tether: sticky, strong, and cheap.

Gear you need for cleaning (and leading):

2 ladders

2 tethers

2 designated tether locking carabiners

2 designated non-locking leading carabiners

Ladders

Most climbers prefer more symmetrical style ladders rather than those with alternating steps on either side. Good ladders are made by Yates, Fish Gear, and Metolius. My new favorite ladders, featured here, are made by Aideer Big Wall Gear from Sweden. They are top quality, durable in the right places, and very lightweight.

(And let’s not call them “etriers” anymore, okay? That's the French word for “stirrup”, and yes, I had to look that up. =^)

Tethers

Tethers is go by many names - lanyard, daisy chain, leash. I'm going to use the term tether to stay consistent.

The long time standard tether was the sewn pocket daisy chain, but these are considered a bit old school. (I’m using one in the photos to show how it looks, but I use a pair of adjustables.) Yates or Aideer make nice ones with flat webbing. Another option is or something like the dual-tether Petzl Evolv Adjust, that uses rope or cord rather then webbing. There are pros and cons to each style, and we’re not going to into them here.

Andy Kirkpatrick has a great article on tethers, which you can read here.

Designated ladder/lead (non-locking) and tether (locking) carabiners

“Designated” means just that. These carabiners stay permanently attached to the top of your ladders and tethers, and you never pirate ‘em for anything else. Ideally, these are a matched pair, and a distinct model and color from any other carabiners you have.

Here's an article that takes a closer look at what type of carabiner you might want for each purpose.

Steep rock variation: ladder only on lower ascender

Big wall expert Chris McNamara recommends only having a ladder on the lower ascender for steep rock. If your jugging technique is less than perfect (like most of us) you may like this too. Check his video below to see the set up.

Travsering pitch variation: one ascender, one ladder, and a Grigri

For cleaning a traverse, it's can be extremely helpful to be able to do a mini lower out and release tension on the rope. Cleaning with a Grigri lets you do this. Here’s an article on that.

Here’s an action video.

Aid Climbing: rig for leading

Having a simple, versatile system for rigging your ladders and tethers is good practice for efficient big wall leading. One good approach: use designated carabiners, one pair for leading and one pair for your tethers. Here's one way to set it up, and some specific gear recommendations.

Having simple, repeatable, and easy to check systems for different components of aid climbing is critical. Your setup for leading is definitely in this category. You'll be repeating the same motion literally hundreds of times on your route, so attention to detail matters!

Once you have it set up correctly:

It’s just about impossible to drop your aid ladders

You use designated carabiners for these important connections, so you’re never patting down your harness looking for a spare carabiner

Transitions (between leading, clipping to anchors, hauling, and cleaning) are faster with minimal futzing around

Let’s look at one good way to get rigged for leading, then get into the gear you need.

Clip a designated lead carabiner to the top of your ladder, gate facing away from you.

Clip your designated tether carabiner to the top of your ladder, in the same place as your lead carabiner.

Done!

There are several ways you can set this up. I’m sharing my personal preference. Try some variations and see what works for you.

The whole shebang:

Tethers are girth hitched to the tie in points of the harness. The belay loop is fine as well.

Tethers are at full extension, so you can reach high placements. (Here, for variety, I'm showing an adjustable tether on the right and a sewn pocket daisy chain on the left. Pros and cons to both. Typically you’d have a matched pair of whatever you prefer.)

Designated lead carabiner is clipped to the top of the ladder.

Designated tether carabiner is also clipped to the top of the ladder.

Fifi hook or adjustable fifi would typically be used, not shown here for clarity.

Ready to lead!

Gear you need:

2 ladders

2 tethers

2 designated tether locking carabiners

2 designated non-locking leading carabiners

Ladders

Most climbers prefer more symmetrical style ladders rather than those with alternating steps on either side. Good ladders are made by Yates, Fish Gear, and Metolius. My new favorite ladders, featured here, are made by Aideer Big Wall Gear from Sweden. They are top quality, durable in the right places, and very lightweight.

(And let’s not call them “etriers” anymore, okay? That's the French word for “stirrup”, and yes, I had to look that up. =^)

Tethers - Pros and Cons (do you even need one for leading?

Tethers is go by many names - lanyard, daisy chain, leash. I'm going to use the term tether to stay consistent.

Some hotshot aid climbers will say, “Don't use a tether on easy aid, it’s faster and easier without it, just be careful and don't drop your ladder.” Well, that might be fine if you have a few dozen big wall pitches under your belt, but for the rest of us, using a tether is standard practice for a reason. When leading, it keeps you from dropping your ladders. An adjustable tether is VERY helpful leading a traverse or roof, or easing onto a hook. When cleaning, it's mandatory safety gear that connects you to your ascender. When you're starting out, I highly recommend using tethers for leading. Once you have enough experience to hopefully not fumble your gear, you can decide if you need them or not.

On the other side, a tether adds weight, cluster, can make you climb lazy if you rest on it too much, and adds time, as you need to extend the adjustable one before the next move. Learn with one, remove it later if you like. Oh, and do bring an extra ladder in case you do drop one. =^)

The long time standard tether was the sewn pocket daisy chain, but these are considered a bit old school. (Benefits: they are lightweight, which can make a difference, especially when ascending.) I’m using one in the photos to show how it looks, but I use a pair of adjustables. Yates or Aideer make nice ones with flat webbing. Another option is or something like the dual-tether Petzl Evolv Adjust, that uses rope or cord rather then webbing. There are pros and cons to each style, and we’re not going deep into that topic here.

Andy Kirkpatrick has a great article on tethers, which you can read here.

Designated lead (non-locking) and tether (locking) carabiners

“Designated” means just that. These carabiners stay permanently attached to the top of your ladders and tethers, and you never pirate ‘em for anything else. Ideally, these are a matched pair, and a distinct model and color from any other carabiners you have.

Designated LEAD non-locking carabiners: Good choices for the are a solid (not wire) gate, narrow key lock nose (so you can slide it into webbing that might be under tension), fairly large size, and a distinct color. The classic Black Diamond ovals work well, and if you like a bent gate, the Petzl Spirit. You’re going to be clipping these lead carabiners into every single piece of gear you place on the wall, so get ready for them to get beat up and retire them when necessary. I still use ancient Kong carabiners that I keep for posterity as they’ve been on a lot of adventures. Note the green color, easy to find at a glance on a busy harness. Here’s a longer article on lead aid climbing carabiners.

Designated TETHER locking carabiners: The lockers let you attach yourself to different components of the anchor, sometimes for hauling, and to clip to your ascenders when cleaning. You don’t need an HMS belay style carabiner here. A standard ”D” locker is fine. Some people like screw gates, some people prefer twist lock. The Edelrid Strike Slider locking carabiner is popular too; it has a low profile and easy-to-use locking mechanism. Here I’m using the Petzl Sm’D, a twistlock.

Try a few and see what works for you. Again, a distinct color is helpful.

Let's look at other rigging options and some pros & cons.

How about skipping the tether locker, and simply clip your tether directly to the lead carabiner?

This might seem like the simplest way to rig it, you do save a little weight, and many people use this setup. But for me it has a few problems. Namely, those transitions, like when you arrive at the anchor and want to clip in with your tethers, you need a locker for that and that means you need to find a spare one on your harness. Plus you need to remove the tether from the lead carabiner, hard when you’re loading it. Or you’re seconding, getting ready to leave the anchor, and you need a locker to clip into your ascenders.

I find it simpler and faster to go with the designated tether carabiner. Try both to try and see what works for you!

If you do try this, set it up as shown above, with the tether on the spine side of the carabiner so it doesn't mess with the gate.

Here's another approach. The tether locker is clipped directly to the lead carabiner, and not into the top of the ladder. This works okay most of the time.

But depending on the shape of your lead carabiner, you may find your tether carabiner, when loaded, starts to grind down on top of the ladder, putting a little more wear and tear on it. By clipping both carabiners to the very top hole of the ladder, you avoid this.

Improv aid climbing - the one ladder method

Do you have a few moves of aid climbing required, but have minimal gear? Here’s a technique that can get you through a tricky part.

Credit for this general method goes to big wall ace Andy Kirkpatrick. It's outlined in his book “Higher Education” and also in a blog article, “Gorilla Aid”. Credit for the improv aid ladder goes to Fabio Elli, from the Alpine Aid chapter of his book, “Hooking Up”.

While the classic two ladder, two tether set up is going to be more efficient for multiple aid pitches, sometimes you may need to improvise with minimal gear. Here’s one way to do it, and it can be surprisingly fast once you get the movement dialed in. (Not to mention, this is gear you already have and it’s less expensive than buying a pair of ladders and adjustable tethers.) You can make the tether and ladder in a couple of minutes.

If you have an actual aid ladder (like my favorites from Aideer) and an adjustable tether, this same process still works.

Gear you need:

Two 120 cm slings

One 60 cm sling

Three carabiners

One quickdraw

From this gear, you make:

A tether, made from a 120 cm sling and a carabiner

A ladder, made from a 120 cm sling, a 60 cm sling and a carabiner

A “fifi”, made from a quickdraw

1 - Make a tether (aka daisy)

The purpose of the tether is to 1) test placements if needed, and 2) hold your weight when you move the ladder to a higher gear placement.

Take a 120 cm sling. Put the sewn bar tacks in about the middle. Tie two overhand knots in the sling, each one about 10 inches / 25 cm away from the ends.

Girth hitch this sling to your belay loop. (Yes, belay loop is fine, but use your tie in points if you prefer.)

Clip a carabiner to the end of the tether.

The length of this tether is pretty important. You want the tether at least as long as your arm at full extension; if you place gear at maximum reach, you need to be able to clip it with your tether. For me, about 5’10” / 170 cm, a 120 cm sling on the belay loop is about right. If you’re taller, basket hitch another 60 cm sling to it, or add a quickdraw.

If you happen to have an adjustable tether that’s long enough, this is a great time to use it. (My Petzl Connect Adjust is too short, my DIY adjustable tether made with some 8.5 mm rope and a Kong Slyde is perfect.)

2 - Make a ladder (See article here)

Take a 120 cm sling. Nylon is nicer to your feet if you have it. Move the stitching to the bottom.

Tie an overhand knot in about the middle.

Pull down some sling material to make an offset step, and tie a second overhand knot at the top end, making a very small loop.