Alpine Tips

Haul bag rigging 101

There are lots of different approaches for rigging your big wall haul bags. Some old school methods still work pretty well, but there are a few more modern approaches that might make things a lot easier.

Thanks to big wall ace Quinn Hatfield @sprint_chef for the “connect two bags with quick links” tip near the bottom of this page.

A few words on hauling, from big wall expert Andy Kirkpatrick:

“Hauling is potentially one of the most dangerous aspects of big wall climbing. This translates to ultra-caution in all parts of your hauling system and interaction with bags, haul lines, docking cords, and pulleys. If you rush and make a mistake, drop a load or have it shift where it's not wanted, you could easily kill someone or yourself. I try and teach climbers to view their bags as dangerous creatures, like a great white shark, rhino, or raptor that is in their charge. The ability to keep them calm and under your control comes down to paranoia, foresight, and heavy respect for the damage they can do.”

There are MANY different ways to set up your bags for hauling. While some traditional methods have served big wall climbers fairly well for a long time, there are some more modern approaches that may make your life a lot easier. Try these different systems, and see what works well for you!

A more traditional / old school hauling setup looks something like this:

Cut off plastic bottle as a knot protector (lifted up here for the photo, in practice you slide the bottle down over the knot)

No swivel

End of haul rope tied directly to master hauling carabiner

Carabiner connects the short strap to the master point carabiner

Bag clipped to anchor with a sewn pocket daisy chain

old school haul setup

Let's look at a few potential issues with this set up.

Nothing really wrong with the plastic bottle. (Sidenote, big wall expert Andy Kirkpatrick suggests using an oil funnel from a car parts store instead of a plastic bottle. The oil funnel has a long, tapered neck that can allow it to slide past obstructions more easily. I haven't tried it but it sounds sensible.)

No swivel. A swivel is somewhat optional and costs a bit, but can definitely save your bags from twisting your rope.

End of rope tied directly to master carabiner. Again, nothing really wrong with this, but if you need to lower out your bags you're going to need an entirely separate rope to do so.

That red carabiner connecting the short haul bag strap to the master carabiner? That can be a BIG hassle with a heavy bag when the master haul carabiner is loaded, because you have to pretty much lift the weight of the bag and have one hand free every time you want to clip or unclip. There are much better ways to attach these two straps.

Finally, that evil sewn pocket daisy chain! That sucker can be very difficult to unclip, especially if the pitch above is traversing. Much better practice is to use a releasable docking cord, more on that below.

Here’s a more modern way to rig your haul bag.

A progress capture pulley such as a Petzl Traxion is attached to the haul bag, not a bight knot. Yes, you haul directly from the pulley. No, it doesn't damage the rope. The pulley gives you a lot more flexibility. You can lift up on the bags with a 2:1 mechanical advantage to transfer them from one anchor point to another, you can use the extra haul rope as a lower out line, you can do a “far end haul” with a 2:1 mechanical advantage if needed, and you don’t need the inverted plastic bottle as a knot protector, because there’s no knot. This is a good place for a triple action carabiner. Yes, the Traxion is expensive.

A swivel goes between the Traxion pulley and the master carabiner. Way less twisting of your rope.

A cam strap connect the long strap and the short straps. This means you never have to lift the full weight of the bags to clip and unclip the carabiner. Clove hitch the cam strap (a 3 footer /1 meter) to the haul point carabiner so you can’t drop the strap. Good place for a triple action (or here, a Magnetron) HMS carabiner. (Side note on the cam strap: After I took this photo, I found out that skotswallgear now makes a very nice 3 foot long cam strap for exactly this purpose, and that's what I'd recommend. Check it out here, scroll to the bottom of his store to see it.

A docking cord attaches the bag to the anchor, not a daisy chain. The docking cord is typically a doubled length of 7 or 8mm cord (about 15 feet / 5 meters) that's attached to the long strap of your bag. With this you tie some sort of releasable hitch onto the anchor, and that holds the weight of your bag. You can release the bag when this hitch is fully loaded, which is a HUGE improvement over hanging your bag from a sling or daisy chain. (Attaching the docking cord to the long strap rather than the hauling carabiner means that when the bag is docked, everything else is slack).

Here's one more tip on where to tie your docking cord (which I unfortunately learned after I shot all these photos). Most haul bags have some sturdy sewn tabs around the opening. If your tie your docking cord to one of these tabs, and around one of the straps, this lets you dock the bag higher up on the anchor, which often makes accessing the bag more convenient.

Tip: Clip a bight knot to back up the Traxion ABOVE the swivel

Just below the Traxion, tie a backup knot (here a butterfly) and clip it with a locker to the carabiner attached to the Traxion. This backs up the Traxion, and gives you a knot you can use to lower out. You can loosely stack all the rest of the unused rope in the top of the bag, or let it hang free.

If the Traxion cam were to open up on some rock nubbin when you're hauling, this backup knot prevents you from losing your haul bag.

Note: It's important to clip this bight knot ABOVE the swivel, and not below it. If you clip the bight anywhere below the swivel, there's a good chance when your bag twists, all of your extra haul rope is going to get twisted around the bag also, no bueno.

Check out the photo below of the correct (left) and incorrect way (right) to do this.

What about two bags?

There are LOADS of different ways to rig two haul bags. The basic concepts (that’ve worked for me) are:

Most folks like the bags side-by-side, but some prefer a smaller bag hanging below the primary bag. Try both and see what works for you.

It’s good to be able to spread the bags laterally if you need to wrestle them around.

You don't want them hanging too far down, so you have to reach uncomfortably low from the anchor. (This is not so important during the day at intermediate anchors, more so at the bivy.)

All connection points need to be unquestionably strong.

You need to able to unclip and separate the bags from one another if needed.

A docking cord connects the bags to the anchor. You can have a separate docking cord on each bag (as we do here) or go with with one single docking cord from the master haul carabiner.

Here’s one way to set it up. From the top down:

Haul rope running through Traxion progress capture pulley, backup knot below traxion, knot clipped with a locker above the swivel

Triple action locking carabiner

Swivel

2 pairs of quick links in swivel. The quick links are unquestionably strong, and give a nice lateral spread to each bag at the belay. (Thanks to Quinn Hatfield for this quicklinks tip.)

HMS locking carabiner attached to long strap on each bag. (Feel free to tape the gates closed if you want to be 110% sure they’ll never open.)

Docking cord attached with quicklink to each bag

On left bag, a 3 foot long camstrap (red)

Here's a close-up:

Here's a fancier way to set it up, from big wall expert Skot’s Wall Gear. Here, Skot is using a pair of gold rappel rings along with a combination swivel and locking carabiner (appears to be the Director Swivel Boss) from DMM. This makes a more compact set up, with zero chance cross loading the rings.

photo: @skotfromthedock, https://www.instagram.com/p/C2nmw-By0-3/

Other hardware for haulbag rigging . . .

There are cool swivels that allows you to open one side. This creates some interesting options; for example you could maybe cut up a PAS tether to get small sewn loops of Dyneema or maybe a pair of quickdraw dogbones, and use these instead of the quick links. I haven’t tried these but looks like they could work.

Here’s a photo: the Petzl Micro swivel and DMM Focus swivel.

Petzl makes a nifty product called the Ring Open. This is a rigging ring that you can open (with a tiny Allen screw, I think), letting you attach a fixed loop. I don't have one of these, but it could be a cool option for setting up your haul bag system.

Like I said at the start, there are many, many different ways to do this. Start with the basic principles, and find a system that works for you.

Director Swivel Boss from DMM. This is the carabiner shown Skot’s photo just above. With this, you can use inexpensive rappel rings instead of the more expensive Petzl Ring Open.

The far end haul

Having a Traxion on the load also lets you set up what’s called a “far end haul”, which at first seems like some sort of sorcery. Here's a detailed article and a couple of how to videos on this technique.

The pre-rigged rappel anchor and belay

Transitioning from climbing to rappelling can take a LONG time. One way to increase your efficiency is for the leader to pre-rig the rappel before they bring up their second. Here's how to do it.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

When you need to rappel the same route you just climbed, the transition at the top can often be a big time suck.

The traditional method of each climber using a tether/PAS to connect to the anchor, each person untying from their respective ends of the rope, threading the anchor, tossing each rope strand, and then each person rigging for a rappel separately, involves a LOT of steps and (usually) waiting. It can also be awkward at tight stances and can take a LONG time, especially with less experienced folks.

Here’s one way to increase your transition efficiency: If you know you need to rappel the route you just came up, the leader can take a minute or so on top to pre-rig the rappel BEFORE the second starts to climb. With this method, you can start rappelling in just a minute or so after the second arrives at the anchor. This can especially be a timesaver if your second is less experienced.

This method is closely related to the backside clove hitch rappel transition; read more about that method here.

I first saw this technique demonstrated by IFMGA Certified Guide Rob Coppolillo. Rob calls it the “BARF” anchor, because the rope from the “BA”ckside of the leader’s tie-in is rigged for “R”appel by “F”eeding it through the anchor, hence the great name. It hasn't caught on yet, what do you think?

As mentioned above, this is absolutely something to practice on the ground in a controlled environment, ideally under the eye of a qualified instructor, before you ever try it in the real world. This process might sound a little complicated, but after you think it through and practice it a few times you’ll see that it’s pretty straightforward.

This might appear to give an uncomfortable belay, but that's not necessarily the case. If your tether of your extended rappel is reasonably long, it works out to be quite comfortable, and you're not twisting your back too much.

Hopefully this is blindingly obvious, but this only works if you are descending a pitch that's less than half the length of your rope. (Which, if you’re considering rappelling the route, should definitely be the case!)

If your second has belayed you to the anchor, and the middle mark of the rope has not yet gone through their belay device, this method will work.

Conversely, if you pull up the rope, and you reach the middle mark before the rope goes tight on your second, this method will work.

If either of these two things are not happening, your rope is too short and you should probably not be rappelling this route!

Advantages:

Fast and efficient transition from climbing to rappeling

Cluster free anchor. No need for multiple leashes clustering up the anchor. You have plenty of room to stretch out and move around a bit, depending on stance. Your position isn’t limited by a short tether or PAS.

Always using the dynamic rope to connect everyone to the anchor. Ropes are stretchy. Stretchy is good.

Only need to toss one rope strand, because the second can stay tied in and takes one strand down with them.

No need to tie a knot in the end of the rope, if the second raps first. This is because the second stays tied in, and the partner is blocking the other strand from moving with their pre-rigged rappel.

What you need:

An easy-to-see middle mark on your rope. Add one if your rope doesn’t have it or if it’s worn away. The Beal rope marking pen is great for this. In the field, you can use tape as a temporary middle mark.

A rappel extension and anchor tether with a locking carabiner. Consider pre-tying this with a 120 cm sling to your harness before you leave the ground; you know you're going to need it, so why not have it ready to go in advance?

Ideally a second rappel device, plain tube style device works fine. Or, you could bring up your second on a munter hitch, see example below..

Here’s the sequence:

This might sound complicated when you first read through it, but once you get your head around the whole process, the steps go very quickly, as you can see from the video link below.

(There are several variations to doing this. I'm going to mostly describe the sequence that Karsten shows in his video.)

Leader arrives at anchor, and clips their tether to one bolt. (This assumes a reasonable ledge to stand on. If it’s a full hanging belay, you can clip another tether into the second bolt so you’re redundant on two pieces.)

Leader calls off belay.

Leader feeds a bight of rope through the rappel chains.

Leader pulls a few meters of rope through the chains, and ties an overhand on a bight. (This knot does two things: it becomes your stopper knot in the end of one strand, and it ensures that the rope can’t pull back through the chains, which might cause you to drop it. Always secure your rope when rigging to rappel!)

Leader unties their retraced figure 8 tie in knot.

Leader pulls rope until middle mark is at the anchor chains.

Leader clips rappel device to their rappel extension, leader feeds both rope strands through device, and goes on rappel.

Leader ties a double strand overhand on a bight (aka “BHK” knot) below their rappel device. (This BHK blocks them in place above the knot, and also gives a convenient place to clip their second plaquette style belay device (e.g., Petzl Reverso) to bring up their second.)

Leader clips their second belay device to the BHK loop, pulls up slack rope, and puts their second on belay. (Lacking a second device, leader could belay with a Munter hitch.)

When second arrives at the anchor, they rig for rappel. (In the video, the second rigs above the leader. Another option is for the second to rig below the leader. If they rig below, the second remains tied in to the end of the rope, so there’s no need to toss it.)

Leader ties a stopper knot, and tosses the one strand of the rope that’s not tied to the second.

Whoever is lower on the rope rappels first.

Like most things in climbing, it’s a much better show than tell. Check out the video below from IFMGA Certified Guide Karsten Delap to see how it's done, from start to finish.

Karsten shows two methods to descend in the video. The first one is lowering your partner, the second one is having your partner rappel. The whole video is great; start at about 6:10 if you just want to see the method in this article.

There are a lot of details in this video, and you may find it easier to watch it full screen in YouTube.

Here's a slightly different way to set it up. In this photo, the anchor is a tree far back from the edge of the cliff, and the leader wanted to stand near the top to have visual contact with his partner. Photo credit, Dave Lottman.

Set up the rappel on the tree

Rappel back to the edge of the cliff

Tie a BHK below the device

Put partner on belay with a munter hitch on the BHK

When his partner arrives, the second gets lowered on the munter hitch, and then the leader unties the BHK and is immediately ready to rappel. Slick! Check out the Instagram reel here.

This is the same set up as shown above, only with a much longer distance between the anchor and the belay, and using a munter hitch instead of a second device.

image credit: @northeast_alpine_start, https://www.instagram.com/p/CoueDaOgg5L/?hl=en

Long approach hike? Push harness leg loops to the side

Do you have a long approach hike and don't want to take a backpack? Here's a simple tip to make that long walk more comfortable while wearing your harness.

My partner and I were at the trailhead, ready to hike in a couple of hours to a moderate five or six pitch moderate alpine rock route in the Sierra backcountry. We had an early start, there were streams for water on the approach and hike back, it was going to stay light late into the evening, and the weather forecast was dry and sunny.

The route was up a long ridge and down the other side, so bringing two backpacks and leaving one at the base was not going to work.

We opted to bring one small pack that the second carried on route, and could be hauled on steeper pitches if necessary. The pack barely fit the rack, two wind shells, and a few snacks. There was no room for shoes, the rope or harnesses. So, we wore the harnesses on the hike in. One person carried the pack, and the other backpack coiled the rope.

If you're going to have a long walk with your harness on, it can be a LOT more comfortable to push the leg loops off to the side. Doing this avoids any chafing or rubbing from the leg loops on sensitive anatomy.

Many harnesses have a plastic clip on the back of the leg loops. Unbuckling this clip can make this even easier.

Great series on climbing history by John Middendorf

American big wall expert and product designer John Middendorf wrote an outstanding series of articles on climbing history in Europe and North America. The historical photos/diagrams are amazing and his writing is solid, definitely worth a look. See them all at his website, bigwallgear.com

Here’s an excellent series of long articles, photos and diagrams of climbing history in Europe and North America, by American big wall expert and product designer John Middendorf.

Excellent writing and historical photos, highly recommended!

On your first visit, you can click the “Subscribe” button on the right side of the webpage to get free updates to this ongoing series.

John has more articles than what’s below, so check the archive section of his website, bigwallgear.com to see all of them.

(For details on his product design and portaledges, go to bigwalls.net)

Below are a few screen grabs from some of the terrific illustrations.

image: bigwallgear.com

image: bigwallgear.com

Did you know early forms of carabiners were used by climbers as early as 1890? I didn’t.

The “meat anchor”: what is it, how do you use it?

If you’re ever in the mildly desperate situation of having to rappel in moderate terrain that one person can hopefully downclimb, and there's no anchors on top, it might be time to pull the “meat anchor” out of your bag of #CraftyRopeTricks.

Photo credit: diagram by Andy Kirkpatrick, used with permission. From his excellent book “Down”, highly recommended!

This article was written with assistance from my expert canyoning friend Kevin Clark, author of “Canyoneering in the Pacific Northwest: A Technical Resource” Lots more on meat anchors in his book.

If you’re ever unfortunate enough to find yourself at the top of some terrain that needs to be rappelled, but has zero anchor building possibilities, you might want to pull the “meat anchor” out of your bag of tricks.

A meat anchor is where a person(s) is the actual anchor, so other people can rappel (or maybe be lowered) directly off of them.

The meat anchor is also known as a “human anchor”. It’s a variation of the classic sitting hip belay.

A meat anchor is often used in canyoning, where you often encounter a wide variety of terrain, with much of it possibly down-climbable and relatively short by alpine climbing standards.

The least skilled and/or heaviest person goes first. The most skilled climber (and hopefully the lightest climber) goes last. In a larger group, the anchor can be backed up by other team members when the first/heavier people are descending.

A meat anchor can also be used to belay someone who is downclimbing, or lowering, if necessary. (You’ll have a lower load on the anchor if they rappel.)

Of course, if you’re able to brace your feet on something, or sit your butt down in the snow, this can be remarkably strong and improves the security of your anchor.

Got more than two people? Share the load. Have them sit in a “train”, clipped to each other's harnesses, and have them back each other up. They can also sit side-by-side, and equalize the load off of each other's harness.

What else helps to decrease the load? Having the rope go over a ledge (which can decrease forces on the anchor up to 66%), having the rappeller go slowly with minimal bouncing, and have the rappeller begin as low to the rock as possible.

Here's a scenario that might be used with a larger group.

You come to a drop that you think is downclimbable, but aren't 100% certain. Set up a meat anchor (backed up), then an experienced party member downclimbs on belay. One of three outcomes:

They report back that it's an easy downclimb, so toss the rope down for them to coil, and everybody downclimbs.

They report that it can be downclimbed, but it's spicy - and might be better for the newbies to rappel. Newbies rappel off the human anchor and best climber goes last.

They have to be lowered, so it's a rappel for every one. Maybe the human anchor stays in position and have people start rappelling, while another person starts rigging an anchor nearby.

You're probably thinking, “What about the last person, what do THEY do? Of course, this doesn’t give many good options for the last person going down. Hopefully they’re able to downclimb. This often might be the case with a guide-client scenario, or a more experienced trip leader with beginners.

The first person down can place protection anywhere they can find it, and clip one rope strand to it. Then the last person can downclimb and clean the gear, while being belayed from below.

This technique is known in some circles as “downleading”, and it can be a good strategy whether or not you’re doing a meat anchor and want to safeguard the descent for the last person. Here’s an article on downleading.

So, this is a Crafty Rope Trick you’re hopefully not doing on a regular basis, but it might get you out of a sticky situation.

Photo: meat anchor with multiple “anchor points”

image: https://www.mountainproject.com/forum/topic/114012583/transition-to-canyoneering

The ZOLEO satellite communication device

A satellite communication (satcom) device can be a crucial tool for communicating with search and rescue if you have a backcountry emergency, and handy to check in with concerned people at home. There's a new player in the field that offers several advantages over the competition. Check out the ZOLEO satcom device.

Alpinesavvy was provided with a free ZOLEO satcom device. This in no way affected my opinion and review. There are no ads, paid product promotions or affiliate marketing links on Alpinesavvy. Whenever I get a free product for review, I'll always tell you about it.

ZOLEO is offering a coupon code with free activation for Alpinesavvy readers. Use the code ALPINESAVVY for a $20 USD discount. (This deal comes as a courtesy from the ZOLEO team. I get $0.00 from this offer.)

An emergency satellite locator/communication device was once something pretty much reserved for sailers, pilots, or extreme expeditions - if your ship is sinking, your plane is going down, or polar bear is gnawing on your leg, you could press the SOS button and (hopefully) someone could more easily find your remains.

The older style, called a Personal Locator Beacon, or PLB, is designed for emergency use, one-way transmit only. Push the big button, and your lat-long coordinates and an SOS is (hopefully) sent via satellite to the appropriate local search and rescue (SAR) team.

The main problem with this type of device is that the SAR team has no idea what your actual situation is, so they don't know what kind of resources to send. Do you need a helicopter for a life threatening emergency, or did you just break your ankle and can wait a day or so for a rescue team to walk in?

The newer style of satellite communication (satcom) devices offer two-way text capabilities, which is a significant improvement. Satcom devices are now a much more mainstream, every-day-carry item for many people, even on a casual day hike.

As I write this in summer 2022, the most well-known satcom device is the Garmin inReach. I’ve used this device several times, and it works fairly well. However, there are newer competitors on the market, and after testing one called the ZOLEO (yes, all caps), I think it offers some solid benefits over the inReach.

The primary design principle of the ZOLEO is to have the best possible messaging experience, without trying to also be a GPS navigation device. I think they succeeded. For actual navigation, I prefer a phone app like Gaia GPS, a printed map, and a compass. Zoleo was named “Product of the Year” at the Third Annual Outdoor Retailer Innovation Awards in Jan 2021, that's pretty impressive!

Before we get into the specifics of the ZOLEO, let’s look at the bigger picture of satcom devices in general.

There are four primary ways to use a two way satcom device. In order of importance:

1 - Request help in an emergency. You can text back-and-forth with SAR to tell them the exact details about your problem. (Pro tip: this makes SAR teams VERY happy!) SAR not only knows your exact position, but also what resources they need to help you. When you push the SOS button, the device sends your message and coordinates to GEOS (the international emergency response coordination center.) GEOS then notifies your emergency contacts and coordinates with emergency responders in your area.

2 - For a delay, but no emergency, you can text your at-home contact something like: “Everything’s fine, but we’re running late. Do NOT initiate a rescue.” Preventing an unnecessary SAR mission is hugely important, and it's a big benefit of a satcom device that many people may not fully appreciate.

3- Using the “check-in” feature to send a quick text to a few trusted contacts at home, usually saying something like “All good, here's my location.” While this is probably the most common use, let’s remember this is strictly optional. It’s really meant for anxious or concerned people at home, and does not directly benefit the backcountry traveller. (People have been adventuring for thousands of years without making “check-in” calls, so it's a luxury, not a necessity.)

Side note on all satcom devices like this: sending check-in notifications is fine, but don’t let a lack of check-in become the basis for a rescue. If your satcom device breaks, gets lost, dropped in the lake, or runs out of power, and you’re fine, the last thing you want is to trigger an unnecessary “rescue” because you didn’t send your daily check-in. This has happened often! Make it clear to anyone receiving your check-in messages that LACK of communication does NOT mean you have a serious problem.

4 - Treating it pretty much like texting on your phone, and sending any sort of text that doesn’t fall under the previous three categories. Long distance hikers can connect with other hikers. If you’re car camping in the boonies, you could text someone else the coordinates of your campsite so they can meet you, etc. You get the idea.

Using the Zoleo for daily check ins on a recent trip down the wild and scenic rogue River in southern Oregon.

What separates ZOLEO from the competition? In rough order of importance:

ZOLEO uses whatever available technology is available (and least expensive) to send or receive messages: Wi-Fi, cell tower, or satellite. This allows a seamless thread of conversation if you move from remote backcountry, to cell coverage, to in-town wi-fi. If you're a long distance hiker or like to car camp in remote locations, this is a very handy feature. Messages sent through the ZOLEO over cell or Wi-Fi do not count toward your monthly limit. Plus, messages sent via cell or Wi-Fi are pretty much immediate. With Garmin, you have to bounce back-and-forth between your phone and satcom device to continue the same conversation.

You get a unique email and SMS number (for texts only, not voice calls) with your ZOLEO. Simply share this email or SMS number with anyone, and they can use any device (computer, tablet or phone) to send you a regular text, without you having to initiate a text thread. This is simple, intuitive, and results in fewer missed messages. Compare this to the awkward Garmin inReach system, where you need to first send a text to someone from the device in order to receive a text back from them. This may sound like a minor difference, but it’s actually a pretty big deal.

“Progressive SOS” feature. When an SOS is declared, ZOLEO users receive step-by-step status updates throughout the incident via the ZOLEO app. You’ll know what’s happening at each step, from pressing the SOS button to the time help arrives, as opposed to just pressing the SOS button and then hoping like hell the technology is working. This is the single most important function of the device, so why not make it more intuitive?

Well designed app. For people who will be contacting you more often, they can download the free ZOLEO app. This allows the most characters per message, and, if they’re on your list of preferred contacts, they can receive check-in notifications and (if activated) Location Share+. You and your designated contacts can use one single app for all your communication.

Longer messages. If you and your contacts use the ZOLEO app, messages can have up to 950 characters. Otherwise, emails are limited to 200 characters and SMS messages are limited to 160 characters. Garmin inReach Mini has a 160 characters limit per text.

Here's a screen grab example of the progressive SOS feature.

General ZOLEO features:

Retail price: $200. Weight is a bit over 5 ounces/ 150 grams. Size is very similar to a deck of playing cards.

It doesn’t have a screen. It has four different colored LED lights and some audible alerts, to tell you the basics like battery charging, whether a message was successfully sent or received, etc., so you don't have to look at your phone. The blinking lights are surprisingly intuitive. (I've seen more than one Garmin InReach with a cracked screen, so the screenless ZOLEO could be considered a benefit.)

ZOLEO has three core features: SOS function, preformatted check in message, and two way text messaging. The SOS and pre-formatted check in message work on the device itself, and don’t require your phone. But, you can use the phone app for both of these functions if you prefer. To send and receive texts, you use your phone and connect to ZOLEO via Bluetooth. Yes, you need a functioning phone to send a text message. (You did bring that auxiliary battery and charging cable for your phone, correct? If you're hiking with a partner(s), have them download the app as well so you can both use the device in case one phone is kaput.)

One touch check-in button. Reassure concerned people at home without excessive fiddling with electronics. You can set up to five check-in contacts on the ZOLEO app. Simply press the “check mark” button on the device, and your contacts will get a message like ”I’m OK”, and your latitude longitude coordinates. This will probably be the most common use of the device, and it's nice that it's so easy, literally one touch.

Impressive battery life. Specs say more than 200 hours, even with checking messages every 12 minutes. That’s 20 days if you have it on 10 hours a day, or about eight days if you left it on all the time. The internal battery recharges to full strength in just two hours via micro USB cable. If you're moving in and out of cell coverage, simply leave the device turned on to make sure you catch all your messages. (Having said that, I am a huge fan of always carrying an auxiliary battery and appropriate charging cables, so I’d encourage you to do the same.)

Weather updates. Via satellite. Zoleo uses DarkSky to get weather info. These weather updates count against your total number of messages. I used this several time during my testing. Weather updates came through in just a few minutes, quite impressive.

Location Share+. Added in 2021, this lets you automatically share your location with up to five check-in contacts, on a selectable interval from every 6 minutes to 4 hours. You and your check-in contacts use the ZOLEO app to view the most recently reported location and “breadcrumb” trail on a map. Personally, I don't see this is being very necessary for most hiking and mountaineering, but if you're a pilot or sailor, it could be more important. This feature is an extra $6 a month.

Not just for camping. Keep it in your car for times when you’re driving outside of cell coverage. It's more than an emergency notification device; depending on where you live or recreate, it could be your primary way to connect to the world.

International travel. Heading on a trek to Nepal, Peru, Kilimanjaro, etc.? This could be a great way to stay connected on your trip. Use the device and a single app to stay in touch, without any concern with your phone being compatible in the country you're visiting, changing SIM cards, etc.

Waterproof, rugged, no screen to break, grippy plastic on the outside. Small clip on the top for a carabiner to wear it on the outside of your pack, but I see zero reason to do this. It doesn’t help with satellite connectivity, but it does greatly increase the chance you're going to lose it if you're bushwhacking. I keep it stashed in the top pocket of my pack, which still allows satellite connectivity if you're sending back-and-forth messages with someone during the day. (I see lots of pictures of people wearing satcom devices clipped to the outside of their backpack, and I never understand why.)

Uses the Iridium satellite network, the largest and most reliable. Keep in mind that these satellites move around. If you have a poor connection, wait a few minutes and a new satellite might move into position; in theory, there should be a satellite overhead about every 10 minutes. If you're in a deep canyon and or dense tree cover, satellite connectivity may be affected. Try to have a clear view of the sky. As mentioned just above, there's no need to have this out in the open to work, inside the top of your pack should be fine. Related note, be patient. Messages can often take several minutes to be sent and received. It's never going to be as fast as cell or Wi-Fi.

The ZOLEO app is available in 7 languages (Italian, German, Swedish, Danish, Finnish, Norwegian and French). From the ZOLEO website, spring 2022: “ZOLEO will only accept credit cards with a billing address in the following countries: Canada, United States and its territories, Australia, New Zealand, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Additional countries will be added over time.”

In addition to the device, you need to choose a subscription plan. There are three levels, depending on how text-happy you are. Data plans start at $20 a month, after three months you can suspend your plan for $4 a month. When you suspend your plan, you keep your dedicated phone number and email address. The amount you pay for the subscription plan is really what the long-term cost of ownership is about, so it's worth taking a close look at this. I won't summarize it here, check the ZOLEO website for details.

So, that's my take on the ZOLEO. It's not a device for everyone. If you hike on mostly frontcountry trails, and you have cell coverage most of the time, any sort of satcom device is probably not needed. But, if you do higher risk activities with off-trail travel in remote areas away from cell coverage (and especially if you lead trips and are responsible for other people) I feel a ZOLEO is well worth the cost, reduced risk, and peace of mind.

Think of it this way: If you use a satcom device just ONCE to help you, a teammate, or another person / group with an emergency situation, isn’t it well worth whatever you spent on it?

Don't just take my word for it. Here are some ZOLEO reviews from solid sources.

What’s that peak? Find out with the PeakFinder app

Try an augmented reality app like PeakFinder to learn the names of visible mountains.

What's the name of that mountain? Climbers have wondered this forever, and now finding the answer is a lot easier.

With an augmented reality phone app like PeakFinder, you can find out in a moment. (Yes, it does show lots of hilltops you may have no interest in, but it does well with the big ones too. )

Photo by my pal Wim Aarts, taken from the amazing viewpoints in the Inyo Range, looking westward at a good portion of the central Sierra Nevada.

If you're ever near Bishop CA, visiting the Inyo Range, enjoying this view and seeing the ancient Bristlecone pine forest is highly recommended.

photo credit: wim AArts

Haul bag straps: connect ‘em with a cam strap

Big wall haul bags usually come with a long strap and a short strap. You haul from the long strap, and need to hoist up the short strap to level and close the bag. It's that hoisting up that's the hard part! Make this a lot easier - replace the traditional carabiner with a cam strap.

Big wall haul bags usually have a long strap and a short strap. The haul rope is connected to the long strap. The short strap is connected / clipped in some way to the long strap. In theory, this allows you to access your bag with all the weight hanging on the long strap, by unclipping the short strap.

The traditional way to do this is with a second carabiner, as shown on the left.

Looks nice in theory, but in reality this is often a serious hassle. If the weight of the bag is loading the master point carabiner, to clip and unclip that red carabiner on the short strap, you may need to hoist the entire weight of the bag, and have a hand free to work the carabiner. With a moderate bag this may not be a problem, but with a full load it can be very awkward and unnecessarily strenuous. Imagine doing this with a 100+ pound / 50+ kg bag, no thanks!

A better method is shown on the right, using a cam strap. Let’s learn how that works!

Instead of that pesky carabiner, use a cam strap to close your bag.

Get a 3 foot cam strap. You can get a two pack of 3 footers for about $15, here's a link for REI. (This is NOT an affiliate marketing link, I simply offer it for your convenience.) Or get a 4 foot and cut it to size.

Tie a clove hitch in the cam strap, and clip it to the haul point carabiner. The clove keeps the cam strap secure so you don’t drop it. Try to keep the buckle close to the carabiner.

Run the cam strap through the short haul bag strap, then back up through the cam buckle.

Now, simply pull down on the cam strap with your bodyweight. Nice, you've created a little 2:1 mechanical advantage. This hoists up the short strap and secures your bag, nice and level.

The cam strap is releasable under tension, making opening the bag just as easy. No more strenuous pig wrestling to unclip that short strap carabiner, schweeeet!

Sidenote: if you’re thoughtful about gear packing, you should hopefully not be diving in and out of your main haul bag during the day. In the morning, try to pull out everything you need for the day, and put it in a smaller day bag or a wall bucket that you use for things like snacks, water, sunscreen, wind shell, etc.

Here’s a more elegant way to do it, with this cool cam strap design from skotswallgear.com. Skot sews a small loop right next to the buckle, so you can clip it to the carabiner rather than using a clove hitch. Note that the strap then passes through the carabiner as shown on the left photo, and then down and through the lower bag strap. (At least that's how I think you're supposed to use it. :-)

Skot was nice enough to send me one for review, thanks!

Skot makes lots of well-crafted big wall gear, like the famous Alfifi, lightweight and easily adjustable tethers/daisys, rope bags, custom webbing for hooks, and more. Check out his website to see it all.

If you use a docking cord that’s tied to the long strap rather than clipped to the master point carabiner, this means that both straps should have no tension on them after the bag has been docked at the anchor. This allows easy access to your bag, regardless of what system you use to close the top. Lots more on docking cords at this article.

Finally, here's a short video showing how it works.

What's in my pack: Rainier gear by Mark Smiley

Check out what IFMGA Certified Guide Mark Smiley takes for a two day Rainier climb up one of the standard routes. (This is a free preview from Mark's new online class class on alpine climbing. Learn more from his website, mtnsense.com.)

This gear list is a free excerpt / preview from Mark's new online course, “The Ultimate Guide to Modern Alpinism”. I haven’t taken it, but I have taken a couple of his other online courses, and they were excellent. Check out all of Mark's offerings at mtnsense.com.

Emmons Glacier, Mt Rainier. Photo by Vaqas Malik

There’s nothing a gearhead likes more than a detailed packing list from an expert climber. Here’s what IFMGA Certified Guide Mark Smiley likes to pack for a two day Mt. Rainier trip up one of the standard routes (Emmons or Disappointment Cleaver). (I've climbed Rainier several times and sure wish I had a few things on this list.)

Of course you don't have to bring everything listed, but it's a pretty good starting point.

Here's a link to the original “course preview” article Mark posted for free on his website, where he names some specific brands that he likes and goes into a bit more detail.

Clothes

Wool t-shirt

Sun hoodie

Thin wind shell

Light puffy

Big puffy

Waterproof shell jacket

Buff

Hat with visor for sun protection

Thin gloves for hot day on glaciers

Showa Temres gloves for cold and wet

Second pair of cold-weather gloves (if forecast is for nastiness)

Softshell pants

Waterproof pants

Socks

Boots (Single layer, with integral gaiter)

Climb gear

Helmet

Sunglasses

Goggles

Headlamp (400 lumen minimum)

Lightweight harness (Edelrid Prisma Guide)

Steel crampons (Mark likes the CAMP Skimo Pure Nanotech crampons, very lightweight)

Ice Axe (50 to 70 cm)

Trekking poles

One mid clip picket

One ice screw (aluminum, 16 or 19 cm)

Petzl Nano Traxion progress capture pulley

Petzl Tibloc

Four lightweight carabiners

Three locking carabiners

Two 120 cm Dyneema slings (or cordelette)

Rope (50 or 60 meters, 8.4 mm dry treated)

Avalanche transceiver

Shovel

Avalanche probe

Pack and camping gear

55 liter pack

2 liter water bag

Steripen water purifier

Lip balm (several tubes)

Sunscreen (small tube or stick)

Satellite communication device

Backcountry navigation app, with GPX file of route loaded onto phone

First aid kit

Sleeping bag (down, 20 degrees)

Compression stuff sack

ThermaRest NeoAir XLite Sleeping Pad

Compact pillow

Two person mountaineering tent

Earplugs

Canister stove (MSR Reactor or Windburner, not Jetboil)

One freeze dried dinner and one breakfast

Spoon

Lunch food, whatever works for you

Try the "T-Step" to stand tall in your aiders

Getting into your second step on your aid ladder on steep terrain can be a strenuous and awkward hassle with the traditional fifi hook. Instead, try the “T-step” method to stand easily in your second step with no fifi.

Note: This method is generally attributed to Ron Olevsky, aka “Piton Ron”, a big wall pioneer who has put up many classic aid routes in Zion National Park. I think Ron’s technique is slightly different than the one shown here, but it's the same general idea.

When leading an aid pitch, it's generally most efficient to stand as high in your aid ladders as you can. (As they say, everything looks better from the next higher step.) But dang, especially on steep rock, it's not quite as easy as it sounds!

If you’re using a traditional fifi hook and trying to stand in your second aider step, on vertical or overhanging rock, you need to maintain a delicate yet strenuous balance of opposing forces.

Your feet are pressing DOWN in your aiders, and your upper body straining UP against the inverted fifi. This often makes your harness creep towards your ankles, not good.

If the fifi sling is even a bit too long, it puts your center of gravity farther out from the wall, which makes you have to maintain a lot more core tension to stand upright, and often the unwelcome sensation that you’re about to topple over backwards.

If you release tension on the fifi for a moment, it could just fall away from the placement that you're pulling against, which really makes things exciting.

Does that sound uncomfortable and not very fun? You’re correct!

When aiding in the traditional manner, this is about what it feels like when you're in the top or second ladder steps . (Drawing credit, from the amazingly talented Mike Clelland.)

image: Mike Clelland, Climbing magazine

Modern tools such as the Alfifi, which is basically a fifi hook welded onto an adjustable tether, can make this process a bit easier, but it still is generally pretty awkward. Overall, standing in your second step in steep terrain is not easy nor intuitive for most people.

Here’s an alternative, simple way to comfortably stand in the second step of your aiders, on vertical rock to overhanging rock, without any sort of a fifi, that eliminates just about all of these problems - the “T-step”.

The effectiveness of this has to do with a few variables such as your height, your shoe size, what kind of aider ladders you’re using, the steepness of the rock, etc. For me, using Yates or Aideer ladders, with a size 10 shoe, and standing about 5’ 9”, I can stand easily in the second step on vertical or slightly past vertical. Your mileage may vary, give it a try and see what it feels like.

Here's how to do it.

1 - Place some gear, clip a single aid ladder to the gear, and stand in the second step with either foot; for this example, your left. Remember to aid climb like you free climb; use your hands in the crack or rock features to step up; don’t just pull on your aiders or gear.

2 - Point the toes of the foot that's not standing in the ladder, here your right, 90° away from the foot that's standing in the ladder. Then, slide your right foot over your left foot. The arch of your right foot should be about over the toes of your left foot, making a shape like the letter “T”. (T-step, get it?) The aid ladder should be between your right calf and left shin. You might have to put your left knee against the wall for a moment and bend your left knee backwards for a moment to make room for your other foot to slide in. Doing this creates a sort of lever that keeps you from toppling over backwards.

3 - Now, you should be able to stand comfortably in your second step, largely being held in place by the muscle of your right calf. You do NOT need a fifi hook, your pelvis is in very close to the rock so you have a good center of gravity and better reach, and you should not feel any strain on your abdominal muscles. Overall, you should be fairly relaxed and comfortable. This is a bit tricky to describe in words, but once you try it you'll intuitively get it. It really feels like a bit of magic the first time you do it!

Doing this, I’m easily able to reach about 5 feet between gear placements.

Stand tall and gain a lot of reach, no tricky three-way balancing and messing with adjustable daisy chains or fifis, and you don't feel like you've done 100 sit ups after you finish leading a pitch. What's not to like?

It might sound odd reading about it, but give it a try. Once you learn how to do this you might get rid of that fifi hook for almost everything.

As with most things in climbing it's a better show than a tell. Watch the video above a few times to see how it works.

Reverse your crampon straps

Ever wonder why the buckle for crampons is on the outside of your ankle, where it requires some spine-twisting contortions to properly thread the buckle, that you can barely see? Yeah, me too. Here's a simple modification you can do on most crampons: by reversing the straps, making it easier and more ergonomic to put ‘em on.

Credit for this tip goes from British Guide Sam Leary, who made the video at the bottom of the page where I first saw this clever trick.

Short version: remove the straps from your crampon heel levers, and reverse the straps. This lets you move the buckle rings to your toe, rather than your outside ankle, which makes threading the strap through the rings and cranking it tight MUCH easier.

It’s time to put on crampons on the side of a dark, steep icy mountain. It’s cold, you have gloves on and lots of puffy layers. You plunk the crampon into the snow, carefully insert your foot, clip down the heel lever, . . . and then attempt the spine torquing, black belt yoga position of twisting to the outside of your boot, trying to thread the strap through the double rings that you can’t really even see . . .

At this moment, you may think, “why the HELL are crampons designed to be put on in this incredibly awkward way?!”

Good news: there’s an easy modification (for most crampons) that makes this process a LOT easier.

Disclaimer #1: The industrial designers at crampon companies (who are of course far smarter than I am) may not approve of this.

Disclaimer #2: This does not work with all styles of crampons. A quick look at yours should tell you whether it works, or not.

Disclaimer #3: If you try this modification and screw it up, your crampon straps might become unusable. Do not try this on the mountain, and you probably shouldn’t try the night before a climb either. You’ll need a few simple tools like scissors (and probably) needle nose pliers. Read this article, watch the video at the end, and be fully aware of how this works before you ever try it for yourself.

Crampons with a heel lever are typically set up with the strap threaded counterclockwise on your left crampon, and clockwise on your right crampon. With this set up, the buckle is on your outside ankle, and you pull the strap forward, or toward your toe, to tighten.

We’re going to reverse this. Instead:

Thread the strap CLOCKWISE on your left crampon, and

COUNTERCLOCKWISE on your right crampon.

This lets you put the buckle up near your toe, where you can see what you’re doing with no contortions and double back the strap with ease. You also tighten the strap by pulling toward your body, which is more ergonomic.

Doing this also puts the buckle on the outside of your foot, which is where it should be, so you don’t accidentally loosen it by clipping the inside of your ankles together.

You could move the buckle to the front without removing it from the heel lever. But if you do this, the buckle will be tensioned on the inside of your foot. This is no bueno, because you’re much more likely to kick it unintentionally with your other foot and release the tension on your strap.

I’m showing it here with my Grivel G12 crampons, so I can’t speak to other brands. According to the video below, it works the same with Petzl and some models of Black Diamond. (It does not work with my Black Diamond Contact universal crampons, because the strap is sewn in to one of the holes on the rear cup and can’t be unthreaded to do this.)

Notes:

For my Grivel G12s, I found that cutting the crampon strap with scissors to make sort of a “V” point, rather than a 45° angle, made it quite a bit easier to thread through the heel lever.

After you make this cut, melt the ends of a strap in a flame and when melted, give it a quick squeeze with pliers to make sort of a hard tip.

When you’re completely done with this project and the straps look good, you MIGHT, repeat might, want to cut off some of the excess extra strap, assuming you’re not going to use these crampons with any larger boots (like ski boots) or loan them to anyone with size 15 feet.

You will probably need needle nose pliers to pull the crampon strap through the heel lever. Take it slow, be patient. A small flat blade screwdriver can help push the strap through too.

Before you thread the strap through the heel lever, lay it all out and figure how the strap is going to lay on your boot, ideally with no twists. With the Grivel‘s, the black leather tab needs to end up lying flat against your boot, on top of the other ring. The way it ended up working for me, the strap is not showing the Grivel logo on the inside of the boot, and it is showing the logo on the outside of the boot. This way means no twists when you’re done. If you do and up with a half twist, it’s certainly still going to work fine, it’s just not as aesthetic as it could be. So, take some time before you thread that heel lever and see that everything is lined up correctly with no twists. “Measure twice, cut once”, as they say.

Do one boot at a time. If you mess it up on the first one, you have your original strap on the other crampon as a reference.

Here's what mine looked like when I was done. The buckle is threaded through the toe piece, and is easily tightened to the outside of the boot by pulling back toward you.

The video below shows this process in detail. Watch it before you try it! Thanks to AMI (Association of Mountaineering Instructors) Guide Sam Leary and LeadingEdge Mountain to show you how it works. She has lots of other solid Youtube instructional videos, give her a subscribe.

Friction can lower forces on an anchor

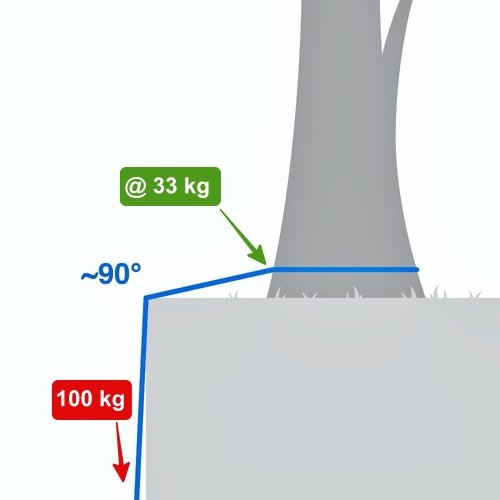

When rappelling, often the rope is going over a ledge. This added friction can make your rope pull more difficult, but it also reduces the force on the anchor, which can be a good thing. The greater the angle, up to about 90°, the less force is put on the anchor.

This tip comes from my pal and canyoning expert Kevin Clark and his book, “Canyoning in the Pacific Northwest: A Technical Resource.”

I did a live body test of this at the rock climbing wall in Marymoor park in the Seattle area. My friend Ryan from @hownottohighline shot the video. See the short Instagram reel and the results here.

Results:

me hanging fully on rope: 190 lbs on anchor

Rope angle from edge to anchor about 50°: 135 lbs on anchor, or about 30% less load

Rope angle from edge to anchor about 10°: 80 lbs on anchor, or about 58% less load

When rappelling, the maximum force on the anchor usually occurs just as the rappeller is passing over the edge on top of the pitch. Once below the edge, the load on the anchor is reduced by the friction from the rope passing over the edge. The more contact with rock the rope has, and the larger the angle, the lower the force on the anchor.

There are lots of factors involved, such as how slippery the sheath of your rope is, if the rock edge is rounded or sharp, whether the rock is wet or dry, the type of rock, etc.

With a rope that runs over the edge at a 45° angle, the load on the anchor can be reduced by as much as 50%.

If the rope passes over the edge at a 90° angle, the load reduction can be as high as 66%.

If your anchor is questionable, that's probably a good thing. The trade-off is your rope is going to be harder to pull.

Let's look at some examples. Let's assume our rappeler weighs about 100 kg.

Example 1: The rope is anchored to bolts hanging over the edge of the cliff top. There is zero friction from the cliff edge. Our 100 kg rappeler puts a 100 kg load on the anchor. Hopefully that should be pretty obvious. (And yes, starting your rappel from a position like this might be a bit difficult.)

Example 2: Instead of using the bolts, the climber is now rappelling from a sling they put around the tree about, say, head height. Yes, this can increase leverage on the tree, but if the tree is stout, it doesn't really matter. A higher anchor point is more convenient to get rigged and start your rappel.

(Sidenote, it's best practice to avoid rapping with your rope around the tree. Doing this can damage the tree, get tree sap on your rub, and make for a very difficult pull. Add a sling instead.)

This makes an angle of about 45° over the edge of the cliff. Once the climber is over the edge, how much force do we now have on the anchor?

Using that best case scenario of 50% force reduction, the load on the anchor is now about 50 kg.

Example 3: Instead of anchoring higher up in the tree, our climber decides to use the base of the tree. (This decreases the leverage on the tree, but might make it harder to rig your rappel.)

This makes an angle over the cliff edge of around 90°. Once the climber is over the edge, what kind of load do we now have on the anchor?

Assuming a best case reduction of about 66%, the tree only sees a load of 33 kg. Good trick if your tree (or other any other sort of anchor) is marginal!

Here are some other techniques to minimize the load on the anchor:

Interestingly enough, you can significantly increase the forces on the anchor in that brief second or two when your feet are on the edge of the rock and you are leaning backwards. This has an interesting force multiplier, even if it's just for a moment. If your anchor is marginal, you probably want to avoid doing that.

To counter this, you can get as low as you can when starting the rappel, perhaps even sliding over the edge. Canyoneers call this a "soft start.”

Pushing the rope down into the rock surface as you go over the edge to help maximize friction.

Keep a consistent load on the anchor, good rappel technique, etc. Don’t jump down the rock like a special forces cowboy.

Use footholds if possible to keep load off the anchor.

Lower from a plaquette - transfer load to Munter

If you're using a guide plate belay device such as a Petzl Reverso, it's important to know how to lower your partner if needed. There are various ways to do this, and some of them are rather complicated. Provided your second can give you a momentary bit of slack, here's a simple way to transfer the load from your device onto a Munter hitch.

Photo credit: diagram by Andy Kirkpatrick, used with permission. From his excellent book “Down”, highly recommended!

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

If you use a plaquette style belay device such as the Petzl Reverso or Black Diamond ATC Guide, it’s important to know how to lower someone if needed.

There are many ways to do this. Lots of them are somewhat complicated, and can increase the risk of accidentally dropping your partner, so learning one or two techniques inside and out is important.

Here’s a lesser known, but simple, way lower from a plaquette - transfer the load from your belay device to a Munter hitch. (It's similar to the Load Strand Direct or “LSD” lower, which we cover in this article.)

This method requires that your second can give you a tiny bit of slack for just a moment, which should be possible the vast majority of the time.

Tie a third hand/autoblock backup to the brake strand. (Adding a “catastrophe knot” a bit further down your brake strand is a fine idea as well.)

Clip an HMS locking carabiner to the anchor.

Tie a Munter hitch in the brake strand and clip it the HMS carabiner.

Ask your struggling second for just a few cm of slack, for a moment. When you get it, it unclip the blocking carabiner from your plaquette. Nice! The load smoothly goes from the plaquette onto the Munter, and you’re ready to lower.

Photo credit: Andy Kirkpatrick, From his GREAT book “Down”,

Finally, here's a nice video that shows the technique. (Demo starts about 1:20)

Single strand Purcell Prusik

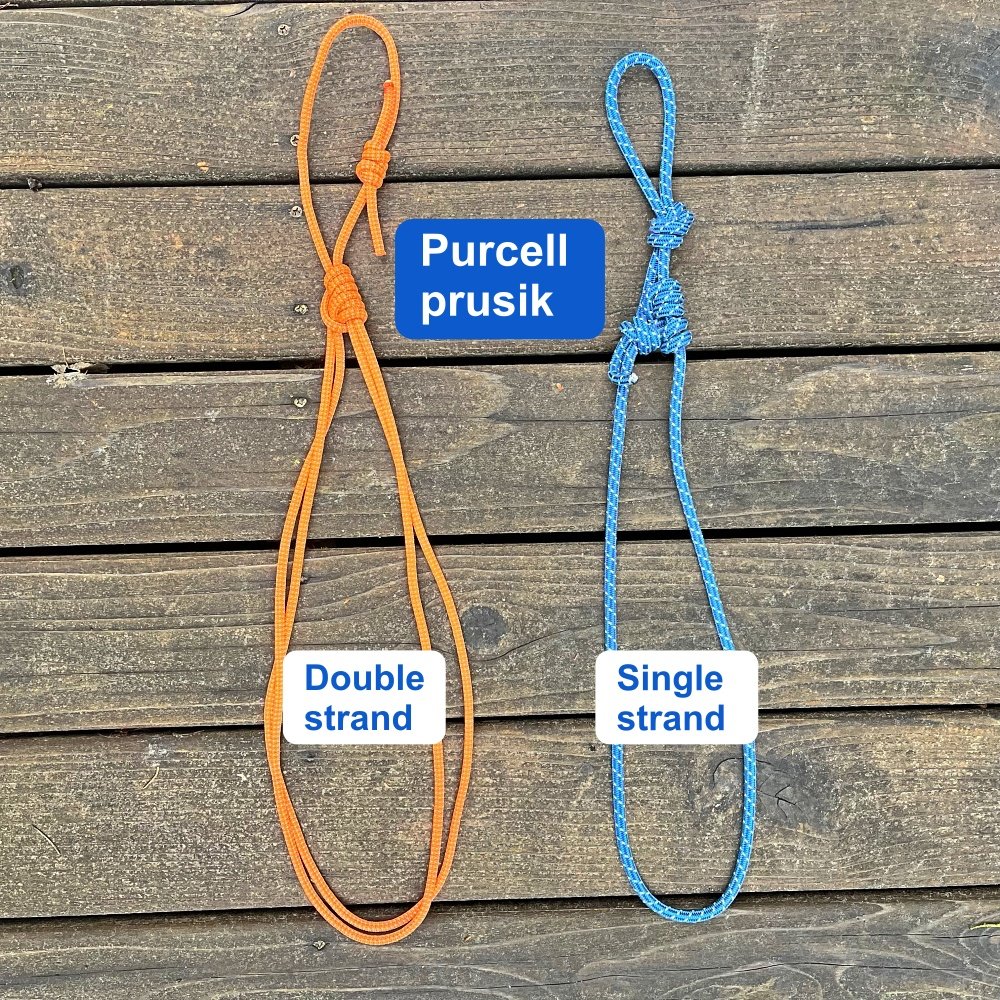

The Purcell prusik is an interesting bit of ropecraft good for certain applications, but it's a bit clunky and tangle-prone. Here's a more streamlined variation: tying it with a single strand.

This Crafty Rope Trick comes from my canyoneering expert buddy Kevin Clark. Check out Kevin's book, “Canyoning in the Pacific Northwest”. Kevin learned it from Ben Lewis, a canyoning expert who made the video at the bottom. Thanks, Kevin and Ben!

The Purcell prusik is named after the Purcell Mountains of British Columbia Canada, and was invented in the 1990s by Kirk Mauthner of Rigging for Rescue.

It’s an interesting, sometimes useful, and sort of klunky bit of ropecraft. (The method I'm showing here is a bit different than how it was first introduced.)

Tied in the usual way, it consists of a prusik hitch sort of tied back onto itself to make an double strand adjustable loop. This has a few applications in self rescue, rope ascending, rigging mechanical advantage systems, adjusting rescue litters, and impressing your knot-nerd pals. One useful feature is that it can be extended under load, which makes it handy for knot passing and other rescue-type stuff. Plus, it’s inexpensive.

But it has a few downsides:

it’s bulky

the twin loops tangle easily

you need two hands to shorten it

it only adjusts from full length to half length (unless you know a certain #CraftyRopeTrick, see below)

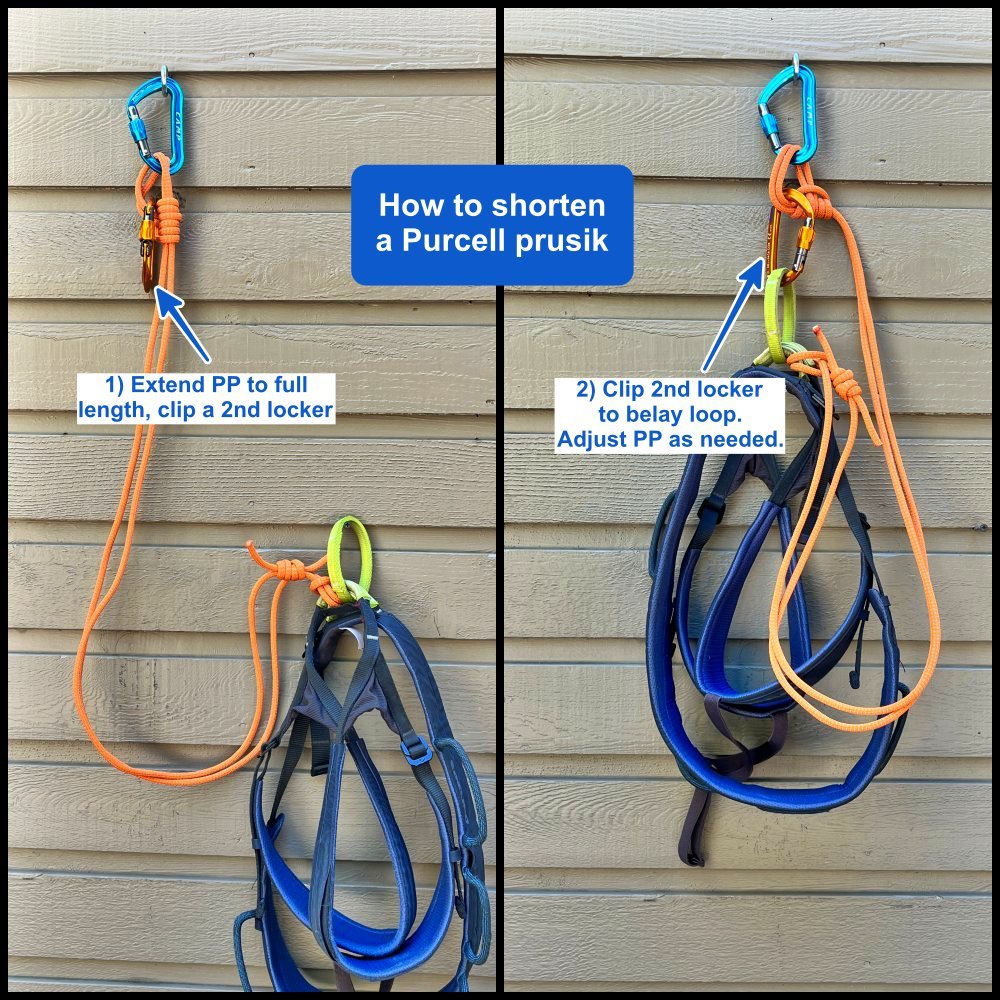

A handful of climbers use the Purcell prusik as a personal tether or ice ax leash or something similar. But the hassles listed here mean it’s not part of everyday gear for most people. (If you want an adjustable tether, a more modern approach is something like the Petzl Connect Adjust, or a DIY version, the Kong Slyde.)

Here’s an interesting variation: the single strand Purcell prusik.

Because it’s tied on a single strand, it’s lighter, lower bulk and less tangle prone than the regular double strand version. (It still has the twin downsides of only adjusting from full length to half length, and needing two hands to shorten it,)

You could use a few different materials to tie it. 6 mm accessory cord works for things like an ice ax tether, or some connection that’s not going to be taking much force. Remember, 6 mm cord is rated to about 7.5 kN, and if you put a knot in this it’s going to be about half that, more like 4 kN, so it’s probably not something you want as a load bearing anchor. (But 7 mm cord is rated to a stout 13 kN, that’s an option too.)

Here’s a single strand Purcell prusik made with about 8 feet of 7mm cord. Much more stout at 13 kN, fine for anchoring.

If you want light and strong, you can tie it with Sterling PowerCord, a svelte cord at just 5.9 mm with a Technora core that’s is rated to a burly 18 kN, plenty strong enough for a serious anchor even with a knot in one end.

Side note: PowerCord is a great choice for a cordelette.

Lots of people think that one of the main problems with the Purcell prusik is that you can never get it any shorter than half the length. So, how do you stay clipped in very close to something? I thought this too for a long time, until I learned this #CraftyRopeTrick from my pal Ryan at HowNot2. He shows it the video at the bottom of this page. (The photo below is with a standard double strand, but it works the same way with a single strand.)

Extend your PP all the way, until there's just a tiny loop of rope at the end. Into this loop, clip a second locking carabiner.

Now, clip this second locker to your belay loop. Now you can clip just two carabiner lengths to anything. Plus, you can increase the size of this loop by feeding cord through, to adjust your distance as needed.

Kind of for fun, I also made a single strand Purcell prusik into a double tether, tied with about 14 feet of 6mm cord. Applications for this . . . ? Aid climbing tethers? Foot loops for ascending a rope? Maybe ice tool tethers? Doing rigging or rope work or routesetting and you have these attached to your tools, drill, bucket, whatever? I was experimenting and haven't used it in the real world, but give it a try and let me know how it works for you.

Now, I get it that lots of people don’t like to carry any kind of designated tether, and that’s fine. I’m putting this tip out there for people who might find it helpful. At the very least, it’s an interesting bit of knotcraft to play around with, so try it yourself and see how it works, even if you don’t think you’ll find a use for it.

Check out the video by Ben Lewis to learn how to tie it. (You’ll probably need to watch it a couple of times, hint hint.)

Finally, here's a nice video from our friends at HowNot2 that discuss how to tie the standard version, and some strength tests on it.

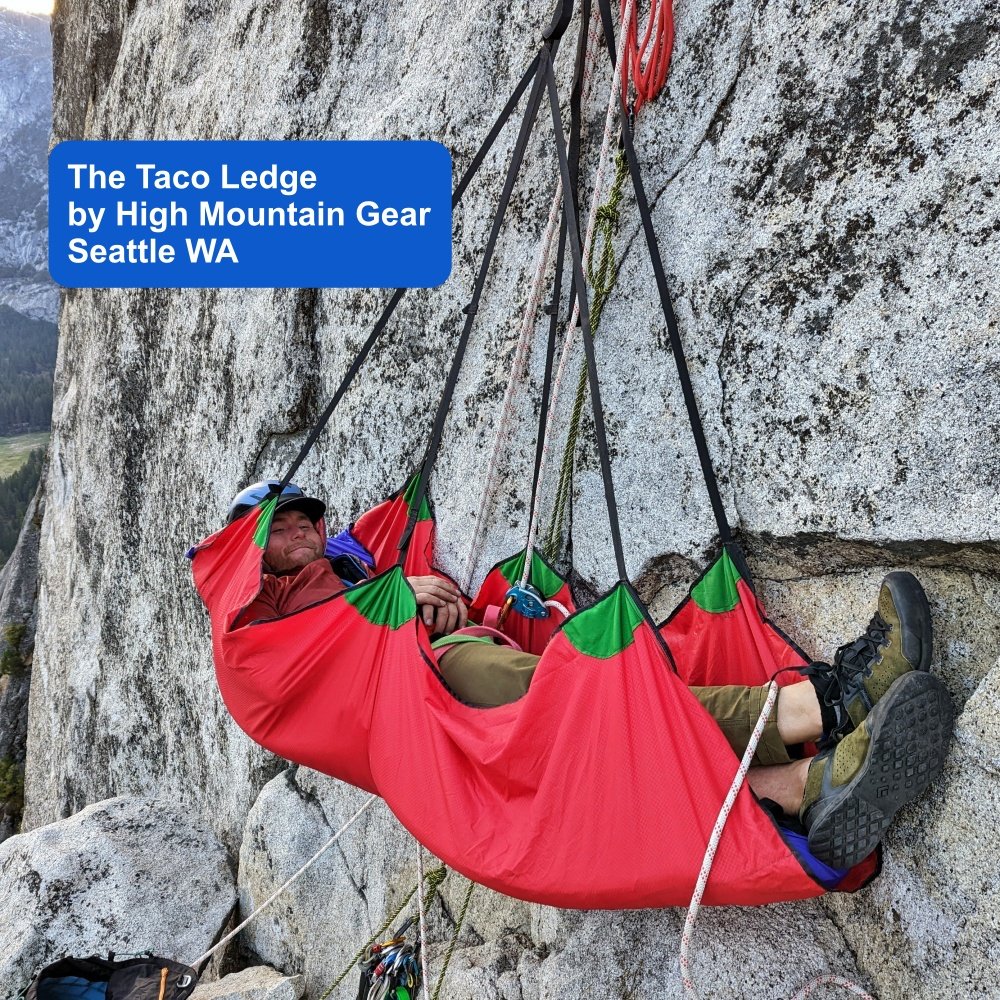

Cool new portaledge: the High Mountain Gear “Taco”

For a multi day big wall climb, you're probably going to need a portaledge. Here's an innovative new option which is lightweight, very compact, easy to set up, and quite inexpensive. Check out the High Mountain Gear Taco, handmade in Seattle WA.

Most photos, shared with permission, are from AMGA Certified Rock Guides Lani Chapko and Sam Boyce, theclimbingguides.com. Connect with them for guided trips and clinics, including big wall instruction. Instagram: @the_climbing_school, Lani: @goatsonropes, Sam: @chossdiaries

Alpinesavvy was provided with a free sample of the Taco ledge for review. This in no way affected my opinion and review. I only recommend stuff I think is great. Whenever I get a review product like this, I'll always tell you about it up front.

Want to get a Taco Ledge? Use the discount code ALPINESAVVY10 to get 10% off your order from High Mountain Gear.

This is not an affiliate marketing link and I do not financially benefit from this deal. I extend this discount as a perk for my readers.

There's no experience in climbing quite like sleeping in a portaledge. After a long day of upward struggle, inching up cracks the width of Donnie Trump’s pinky finger, wrestling both the haul bag and your mental demons, you’ve reached the bivy. Time to set up the ledge, kick back with bare feet and a well-earned tasty beverage, watch the afternoon light fade to evening, and hear the Doppler “swhoosh” of the swallows streaking by. It’s a sublime experience you’ll remember for a lifetime.

For big wall vertical camping, you’re going to probably need a portaledge. Yep, they are solid and comfortable, but you pay a high price in cost, weight, bulk, and (usually) set up hassle.

Here’s an intriguing alternative that addresses all of these issues: the Taco inflatable hammock. It’s made in Seattle by climber and sewing ace Kyle Willis and High Mountain Gear.

It’s a single point hammock matched with an inflatable sleeping pad. The pad adds a lot more rigidity and comfort than a plain hammock, creating a ledge that’s inexpensive, ridiculously lightweight, very compact, reasonably comfy, and super easy to set up.

Cost: $299

Weight: 1 lb 13 oz / 822 grams

Size: 76" x 49"

Packed size: without a pad it packs into a cylinder about 5" diameter by 10" tall (not much bigger than a Nalgene water bottle!)

Pad dimensions: 18"-26" wide and up to 78" long. (Pad is NOT included in the price.)

It’s an intriguing option for certain big wall applications where you want to minimize your load and save money to spend on . . . I dunno, maybe a few more Totem cams?

Now, if a weight under 1 kg is not already light enough for you, Kyle is working on a new model made from Dyneema fabric that comes in close to a ridiculous 1 pound for the ledge alone. Yes, this version will be more expensive, but if shaving grams is important to you, it’s an option.

You can rig the Taco not only as a horizontal ledge to sleep in, but also as a reclining lounge chair. If you're looking at a multi hour belay session, it's hard to get much more plush than this. The Taco is so compact and easy to set up, that you might even want to keep it in the day bag and use it at every belay as a chair, if you're doing long pitches.

One big advantage of the Taco ledge is the ease of setup and breakdown. As anyone who’s tried to set up a ledge in the dark and has been tempted to reach for the wall hammer to persuade that last aluminum bar into position knows, this is a significant benefit.

You insert your sleeping pad and adjust the straps that secure it on the ground before liftoff. The pad stays inserted for the whole climb. On the wall, setting it up is pretty much clipping the Taco to one good suspension point (it needs about 5 feet of hang) and inflating the pad. To break it down, simply open up the air valve, roll it up, fold the sides inward, and put it in a stuff sack. This literally takes just a few minutes.

The base model comes at a very reasonable price of $299 (pad not included) as I write this in Oct 2024. A couple of highly recommended add-ons are a zipper storage pocket (perfect for big wall beverages, headlamp, etc.) and a stuff sack.

Note that nothing on the Taco is rated to be a safety connection. Always stay clipped in with a real tether/rope to a real anchor. (A tip I learned from big wall expert Mark Hudon: take a completely separate short length of rope, about 6 meters of 8mm rope, just for tying yourself in and moving around the bivy.)

Learn more: Check out this in-depth article from theclimbingguides.com with several videos covering installing the pad, hanging the Taco, and setting it up in lounge chair mode.

Below: Taco time on El Capitan. Photo by big wall ace Kevin DeWeese, @failfalling

image: Kevin DeWeese, https://www.instagram.com/p/CdOQBL6rWUu/

Pro tip from Kevin: Twist a carabiner in one of the straps to shorten it a bit if you need to even out the ledge; see photo below.

FAQ . . .

What's the best application for the Taco? Probably longer routes that may have a fair amount of natural ledges, but you still need to spend a few nights out and want to travel light, have easier (or zero) hauling, and hopefully climb in predictable dry weather. Think the nose on El Capitan, NW Face of Half Dome, and classic routes in Zion like Prodigal Sun or Spaceshot. If you're planning a climb longer than a few days, or in questionable weather, you probably want to go with a more traditional portaledge with a dedicated rain fly.

Is it like the G7 Pod ledge? The G7 Pod is another innovative design. That ledge is fully inflatable with no metal frame. Like the Taco, the G7 is lightweight, compact, and is fast to set up. It also appears more durable, and has an optional rainfly. I’ve never tried it, but it looks plush and has great reviews. It’s also $685 (with a rainfly an additional $375). The Taco is $240.

Tell me about the pad. A proper pad, which is NOT included, is critical to the functioning of the Taco. Without a pad, it’s an uncomfortable single point hammock, like big wallers suffered with 40 years ago (see photo below). The optimal pad is 72 inches with horizontal baffles, like the Thermarest Uber Neo Air. Field testing shows a pad with a grid works okay, and a pad with vertical air baffles does not work very well, “taco-ing” your shoulders, which is what we’re trying to avoid. A pad that’s tapered toward the feet and is wider at the shoulders seems to work better than a rectangular pad.

Can I get a double? No. Get two Tacos and stack them vertically.

What about a rainfly? YES! Check out the Gordito rain fly from High Mountain Gear, made specifically for a Taco Ledge.

Schweeet! Where do I get one?

Use the discount code ALPINESAVVY10 to get 10% off!

The hammock concept on big walls has been around for a very long time. Check out this classic photo from 1964 with Tom Frost, Royal Robbins, and Yvon Chouinard on the FA of North America Wall, El Capitan. Nope, that is most definitely not a comfortable way to spend the night. Photo credit, Tom Frost

image: Tom Frost, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tom_Frost_-_Tenement_flat_-_1964.jpg

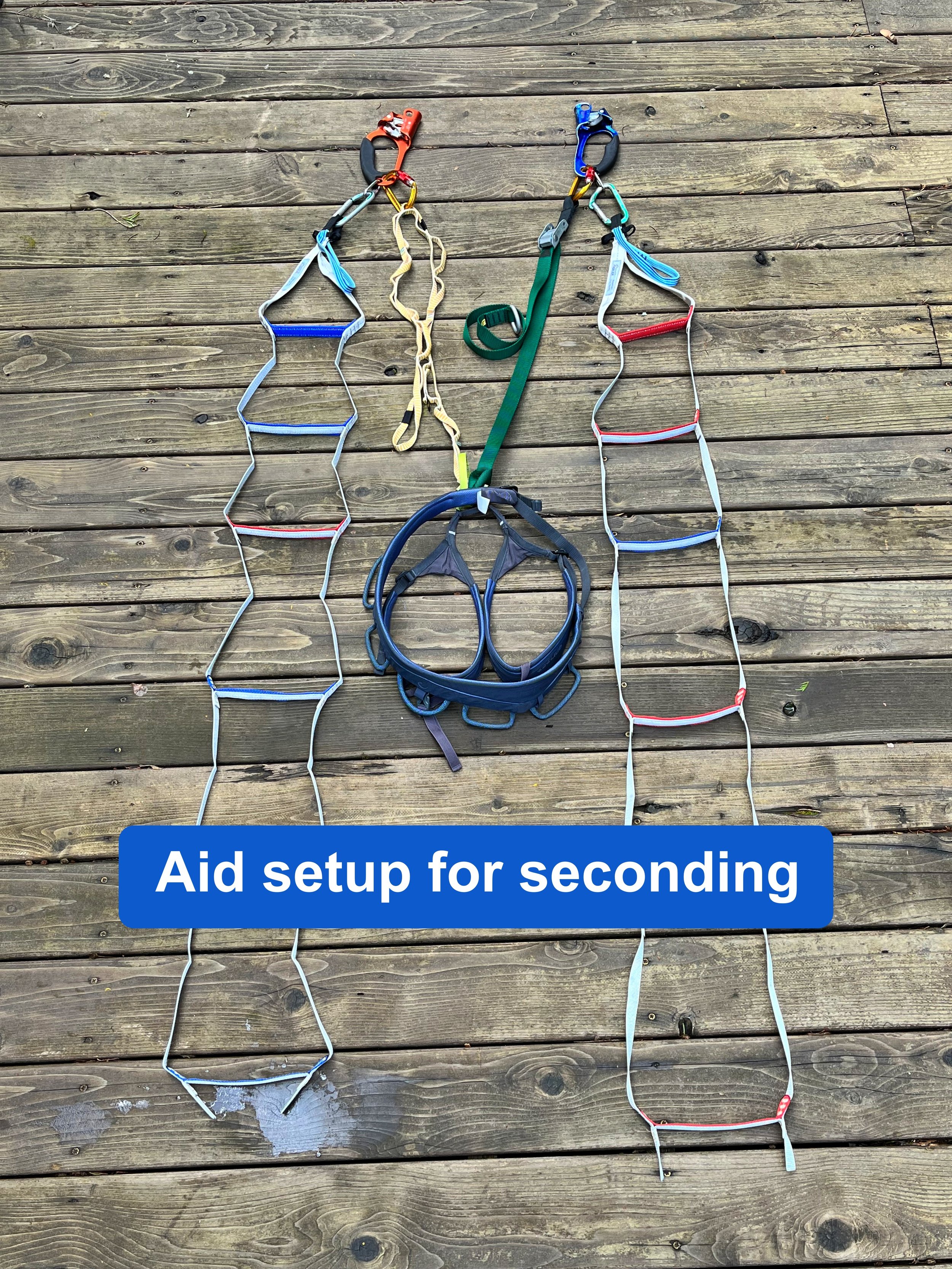

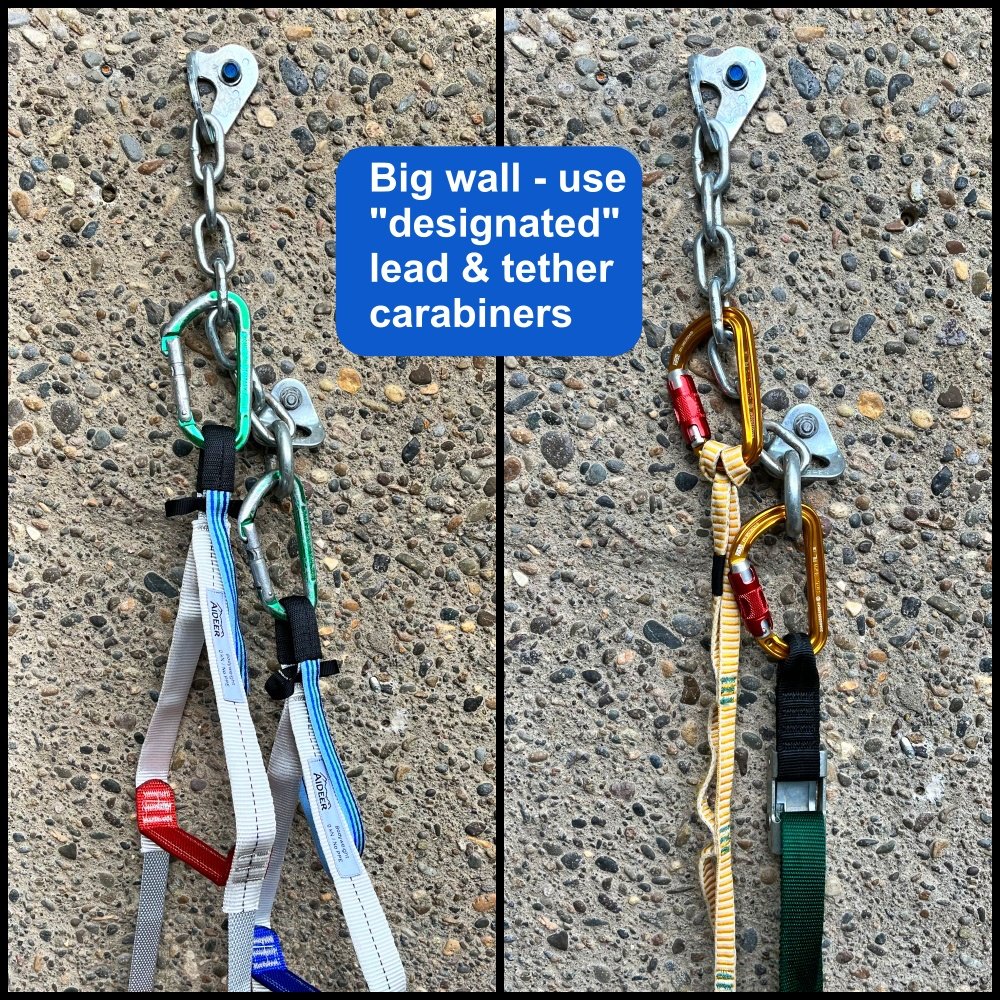

Aid climbing: rig for seconding

Having designated carabiners for your ladders and tethers, and having your tethers set to the correct length, is key to efficient ascending and cleaning on a big wall. Here's how to set it up, some specific gear recommendations, and pros and cons of alternative methods.

Having simple, repeatable, and easy to check systems for different components of aid climbing is critical. Your setup for seconding and cleaning is definitely in this category. When you're jugging thousands of vertical feet and and cleaning hundreds of placements, you really want to have this dialed.

Once you have it set up right:

Your tethers are set at the perfect length for efficient ascending

You use designated carabiners on your ladders and tethers, so you’re never patting down your harness looking for a spare carabiner

Transitions (between leading, clipping to anchors, hauling, and cleaning) are faster with minimal futzing around

First off, let's look at an ascender modification.

Most handled ascenders (except the newer Petzl ones) have two holes near the bottom, one large one small.

Add a small (5mm) stainless steel quicklink to the small hole. Crank it tight with pliers. Now you have a designated clipping point for your ladder, which goes on a snapgate carabiner. This not a mandatory mod, and many climbers do just fine without it, but I find it’s quite convenient. Here's an article with the whole scoop.

The main benefit to this is that it lets you more options to easily separate your ascender and ladder if you ever need to. Examples: Cleaning a traverse, when it might be convenient to clip the ladder to the next piece of gear and stand on it, to unweight the piece of gear you need to clean. Or, when you arrive at the anchor and you want to clip your tether directly to a bolt but you're still standing on the ladder, separation like this lets you do it.

Close up of the business end. The quicklink makes a convenient place to clip your ladder that's entirely separate from your tether.

Here’s how it looks on the rope.

Let's look at one good way to set up for cleaning. There are variations on this, but here’s what works for me. Experiment and see if it works for you too.

We’ll first look at the classic two ascenders and two ladders. This works best on lower angled rock up to about vertical, with the route not traversing too much. It does take a little practice so you don’t look like a marionette having a seizure.

There are other setups that can be more helpful if the rock is very steep, or if the pitch is traversing a bit. We’ll look at those at the bottom of the page.

Cleaning Tip: One simple way to keep things reasonably organized when you’re cleaning: get two 60 cm slings, and put one over each shoulder. Clip cams and wires to one side, clip slings and carabiners to the other. At the anchor, you can remove each sling, attach it to something solid and start re-racking on the larger, more comfy primary leading gear harness.

The whole shebang:

Tethers are girth hitched to the tie in points of your harness. The belay loop is fine as well

Both tethers are set at the correct length for efficient jumaring (more on that below)

Designated lead/ladder carabiner is clipped to the quicklink

Designated tether carabiner is clipped to the large hole on the ascender. Locker is mandatory

Ready to clean!

Tether length for seconding

When leading, you have your tether at full extension, because you need to reach high. However, when seconding, it’s critical that the tethers be shortened up to the correct length. If your tether is too short, you’ll make short, choppy, inefficient movements up the rope. If your tether is too long, you can’t reach the handle of the ascender from the rest position, and you’ll have to do some ab-busting contortions to reach it. Here’s an article on how to rig that correctly.

There’s a sweet spot in the middle, and here’s how to find it: With your tether girth hitched to your harness, clip the carabiner and an ascender to the end. Pull on the adjusting strap (or clip a daisy pocket) until the bottom of the ascender carabiner is at your eyebrows. Most people find this to be just about the perfect length.