Alpine Tips

How to ice climb - video tutorial series by Will Gadd

Canadian ice climbing expert Will Gadd posted an excellent series of ice climbing tutorial videos on Youtube. Video production is excellent, and Will’s vast experience, good humor and teaching ability comes through in every one. Highly recommended!

image: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nwl4XAdIKGM

Canadian ice climbing expert Will Gadd and Black Diamond teamed up to make an excellent introductory video series about ice climbing techniques. There are nine videos in the series, most are about 10 minutes long. (Pretty sure these came out just as I write this, late November 2022.)

Topics include:

footwork

how to swing

steep ice technique

dry tooling

screws

clearing bulges

V threads

pick sharpening

Will radiates his usual positive energy, vast experience, good sense of humor (and humility), and overall stoke. Solid tips from a solid guy, good video production quality, highly recommended!

Search YouTube for “Will Gadd how to ice climb”, or see the whole playlist from this link.

Tame skinny ropes with a daisy chain

Long lengths of skinny rope, such as a 6 mm rappel pull cord, can easily turn into a hopeless tangle if you're not careful. Solution: the daisy chain. This “crochets” a rope into a series of short chain links, reducing the length by about a factor of six. A daisy chained rope is pretty much impossible to tangle when stored, and easy to deploy when you need it.

Daisy chain, lineman’s coil, chain sinnet. A few different terms that mean the same thing: to do a little crocheting on your climbing rope to help it stay tangle-free in your pack.

Daisy chaining your rope can be especially helpful when using a long length of tangle-prone skinny rope, such as like the Petzl PURline or RADline, or a rappel pull cord. The photo above shows a 30 meter RADline.

(It also works great to bundle up long electrical extension cords, which is where I first learned this trick doing construction way back when.)

If the rope is inside your pack, a daisy chain lets it smoosh it around and better fit the contours of your backpack and other gear, as opposed to a butterfly coil. If you’re carrying your rope draped over the top of the pack, then a butterfly coil is probably a better choice.

And, even if you don't have a skinny rope to deal with, it's still a fun rope trick to play around with and practice, so get out your cordelette and give it a try!

How to make a daisy chain

I like to start at the middle of the rope. (Your rope DOES have a middle mark, right?) Make a girth hitch, reach one hand through the loop you made, and grab two strands of the rope. Pull these two strands through the girth hitch loop, forming a second loop. Reach through that loop, grab two strands, and repeat. (Congrats, you just learned to crochet.)

When you’re done, the rope will be in a series of what looks like chain links. In link, you’ll see six strands of rope. So, the daisy chain effectively shortens your rope by a factor of six. That means your 60 meter climbing rope is now a much more manageable 10 meters long. You can take a daisy chained rope and stuff/smash/smoosh it around all you want, and it’s never going to get tangled up.

To deploy the rope, find the ends of the rope and pull on them. The entire daisy chain should magically unravel itself, and you should be left with a nicely flaked rope with both ends on top.

(Another good approach for managing a long length of skinny rope is a rope bag. It doesn’t need to be fancy, a reusable plastic grocery bag with sturdy handles works fine, packs down very small, and weighs just 2+ ounces / 60ish grams.)

Like most everything to do with knots, it’s a better show then a tell. Check out the video below to see how it’s done.

Petzl - RADline vs PURline comparison

Petzl makes two highly specialized ropes suitable for alpine climbers, the RADline and the PURline. Both have a static Dyneema core, both are 6 mm, and both are designed for different applications. Here's just about everything you need to know about these ropes.

Petzl offers two flavors of highly specialized ropes for alpine climbers: the RADline and the PURline.

What's with the acronyms?

Can I lead climb on ‘em? (Quick answer, NO!)

Are they both basically the same thing?

Can I really use a 6 mm rope for something practical, or is this a dog leash?

They both have a lot of similarities and some important differences, so let's get into it.

Similarities of RADline and PURline

Both are hyperstatic (just 2% stretch!) and NOT meant for lead climbing.

Both are 6 mm.

Both have a core of HMPE (High Modulus Polyethylene), commonly known as Dyneema. This makes them very strong (12 kN RADline, 15 kN PURline) and cut resistant.

Because of the HMPE core, these ropes absorb essentially zero water, so they're much lighter when dragging through the snow.

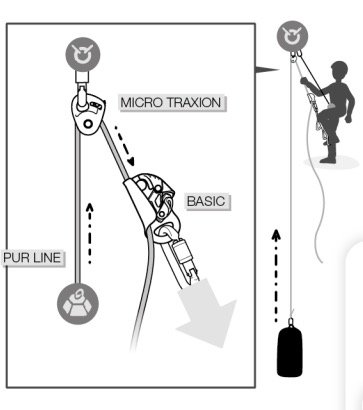

Both have a sheath that’s bonded to the core, which means you can use them for hauling with ascenders, such as a Tibloc, Micro/Nano Traxion progress capture pulleys, and even larger ascenders, see diagram.

The ascender/pulley compatibility may be confusing, because the technical documentation for the Tibloc and Traxions specify a minimum rope diameter of 8 mm. Apparently it's fine to use these devices on these 6mm lines. Petzl says that these ropes can take about a 4 kN load with these devices before the sheath will be damaged. See Petzl test results on this here. (Summary: Use a Traxion on RADline only.)

Because of the small diameter, both are highly prone to tangling. Using some sort of rope bag is highly recommended. If you don't have a rope bag, coiling it with a daisy chain (aka chain Sinnet or crochet) works pretty well too. If you tie the bottom end of the rope to your rope bag, you can toss it for rappel and quickly deploy the rope perfectly, even in high winds.

A basic nylon stuff sack works okay as a rope bag. However, it’s difficult to stuff the rope in a floppy bag. Here I’m using an ice screw bag made by High Mountain Gear. It's the perfect size, has a lid that stays open for rope stuffing, has a couple of attachment points, is extremely sturdy, and works great as rope bag.

RADline details

Intended use: crevasse rescue, glacier travel and rappelling.

Made for “Rescue And Descent”, hence the name.

Static ropes can be great for glacier travel, provided you have excellent rope management, i.e., minimal slack. Because it's static, the distance of any fall will be minimized - less rope stretch. On the downside, because it's static, if the people on top have extra slack out, it can give them a powerful yank. If using this rope for glacier travel, be very mindful of distance between partners and watch your slack.

Weight: 22 grams per meter (about half the weight of an 8mm dynamic rope)

It has a rougher sheath for better handling, more friction on ice and snow when arresting falls, and for extra friction when rappelling.

It's a bit more supple, which makes it a bit easier to handle and to stuff into your pack.

It's orange, which gives better contrast on snow.

Rappelling on this is easier than the PURline, but still can be challenging because of the small diameter. Definitely learn some techniques to increase friction, such as shown in this article. You also use specialized rappel devices made for small diameter ropes such as the Black Diamond ATC Alpine guide, Grivel Scream, or the Edelrid Mago 8 (see below).

I tested using an 6mm Edelrid Aramid cord as a four wrap prusik on both ropes. This held my body weight on the RADline, and not on the more slippery PURline. A Tibloc may be better choice than a prusik on rope this thin.

Comes in lengths of 30 and 60 meters.

Supposedly has a 10 year rated lifespan, which is longer than the typical dynamic rope.

Sorry, no nice diagrams from Petzl. =^(

The Grivel Scream is one of the few devices rated for ropes between 5 and 8 mm. If you are a ski mountaineer and plan on doing lots of rappelling on a RADline, this might be a good one to get. (Note, I don’t have one of these and I've never tried it. I love the name!)

image credit: Grivel

Another rappel device option is the Edelrid Mago 8. This is a modified figure 8 with a few extra horns on it, similar to rappel devices popular for canyoneering. This device is rated for ropes from 6mm to 9.5mm. (Note, I don’t have this device and I've not tried it.)

image credit: Edelrid

PURline Details

Intended use: rappel retrieval/tag line or haul line.

Made of “PURre” Dyneema, hence the name.

Weight: 20 grams per meter, a hair lighter than the RADline (about half the weight of an 8mm dynamic rope)

The PURline is both slippery and stiff, which makes it easier to pull over rock and a bit less prone to tangles when you're using it as a rappel tagline. Surprisingly durable.

It's white, which gives it better visibility on rock.

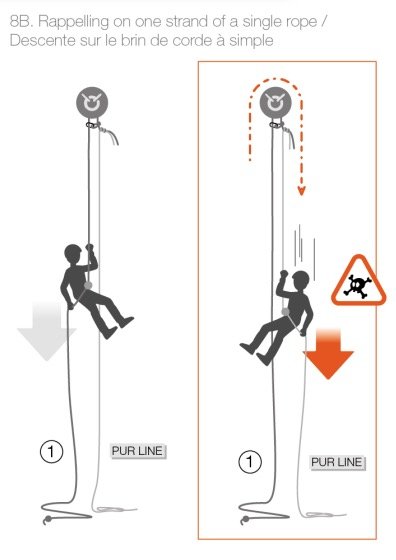

Because it's so slippery, rappelling directly on it with a standard device is not recommended, even if you take extra steps to add friction. A super Munter might work. (Don't even think about rapping with a Grigri on one strand of PURline.)

When used as a tagline, Petzl recommends using TWO stacked opposed overhand knots to join the ropes. The standard flat overhand bend is NOT recommended, see diagram below.

Hopefully obvious, but when used as a tagline, you should rappel on your normal climbing rope of a larger diameter, and only use the PURline to pull the rope down, see diagram below.

NOTE: Rappelling on a Reepschnur / knot block, and two ropes of different diameters, opens up LOTS of concerns and considerations, more than I can get into here. Definitely practice in a controlled environment with a qualified instructor before you ever do it for real.

Rappel tip with a tagline like this: thread both strands through your rappel device, as this can help remove twists as well as keep the tagline attached to you. (That’s the one strand you need to pull, so you NEVER want to let the tagline swing/blow out of your reach!)

The PURline comes in lengths of 65 meters and 200 meters. Does 65 meters sound like a strange length? It did to me, until I learned that the clever Petzl gear gnomes chose this to account for the dynamic stretch of a typical 60 meter rope that you're using it with. (And that 200 meters? Maybe that's for fixing lines on K2 or something.)

Hauling tip: If you're hauling a load or pulling down a rappel tagline, a small diameter rope is slippery and rough on your hands. Here's a quick tip: add a Tibloc, Micro Traxion or similar ascender onto the hauling side and clip a large carabiner to it as a handle. It’s much easier on your hands!

Best use: hauling and rappel pull cord.

image credit: https://www.petzl.com/INT/en/Sport/Ropes/PUR-LINE-6-mm

For hauling, the PURline is compatible for with the Petzl Mini/Micro Traxion (and even larger ascenders like the Basic or Ascension.)

image credit: https://www.petzl.com/INT/en/Sport/Ropes/PUR-LINE-6-mm

Caution: rappel on the larger, blocked strand of rope.

PRACTICE using knot blocks and retrieval cords with a qualified instructor before ever using them for real! There are lots of ways to screw this up!

image credit: https://www.petzl.com/INT/en/Sport/Ropes/PUR-LINE-6-mm

Caution: Petzl says to use a stacked, opposed overhand to connect the two ropes. Flat overhand bend is not recommended, figure 8 bend definitely not recommended.

Petzl has a very detailed article on their website about recommended knots to use in RADline. The short version: flat overhand bend or stacked overhand is recommended. Have rope tails of at least 30 cm and dress/ snug down the knot very well.

image credit: https://www.petzl.com/INT/en/Sport/Ropes/PUR-LINE-6-mm

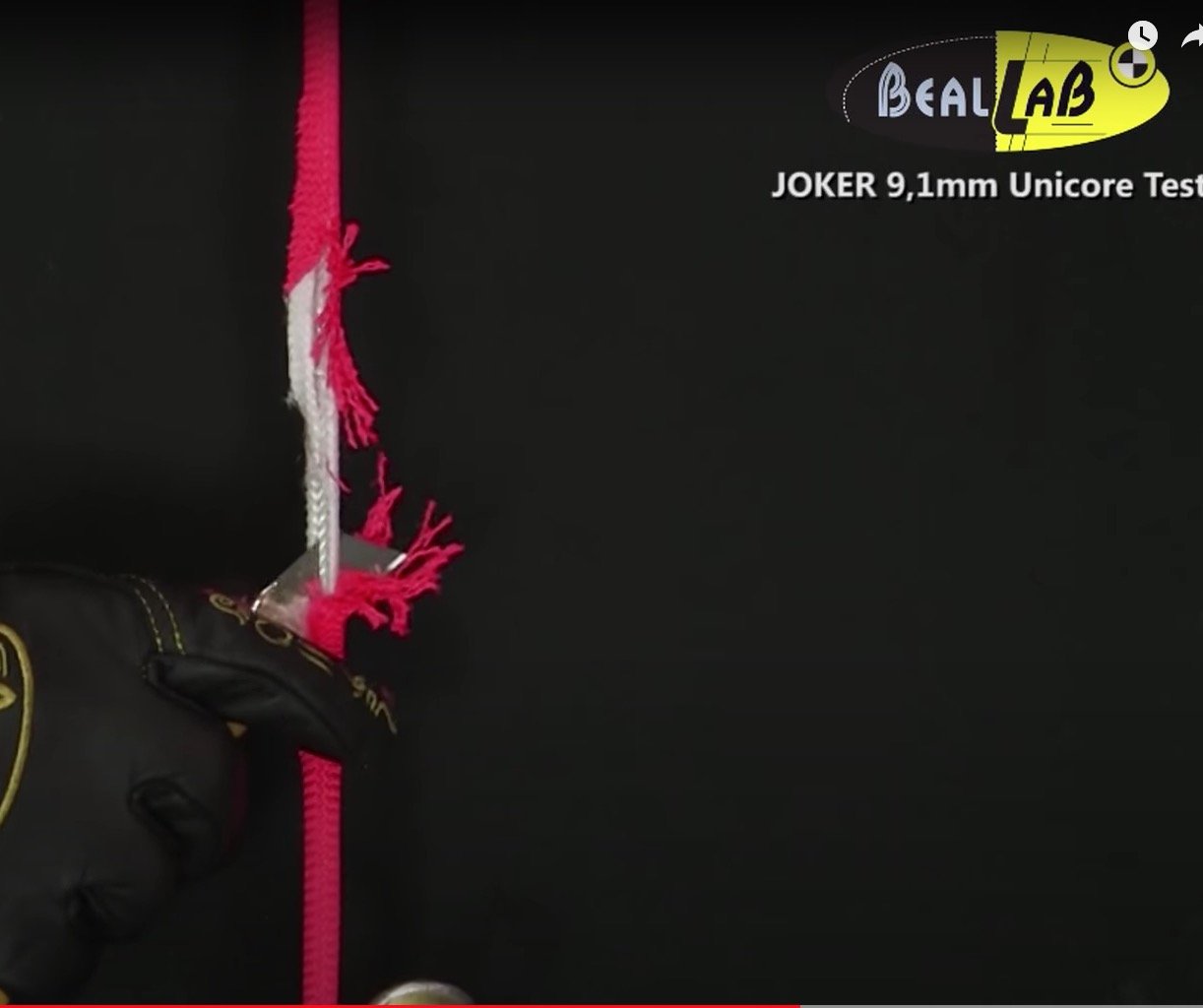

What’s a “Unicore” rope?

A regular climbing rope is made with the core and the sheath as two separate components. A Unicore rope, made by the French company Beal, bonds the core and the sheath together, resulting in a rope that has much greater resistance to catastrophic damage.

image credit: screengrab from: https://youtu.be/K83a5zH014I

A standard climbing rope is made of two parts: the dynamic stretchy core, and the colorful protective sheath. (Another term for this is a ”kernmantle” rope, from the German, “kern” = core, “mantle” = sheath.) Andy Kirkpatrick has a memorable way to describe this: The sheath of the rope is like the muscles around your intestines, it holds all the soft inside parts together and protects it. =^)

Typically, the core and the sheath are manufactured separately and are not connected together. Most of the time this works great, but if the sheath of the rope gets damaged, especially when the rope is under tension, it can separate dramatically, also known as a “core shot”. This can: 1) cause you to wish you brought your brown pants that day, and 2), immediately retire your rope (if you're still alive.)

Thankfully, modern climbing ropes are plenty durable enough in most applications, and we're not hearing about ropes regularly self-destructing. However, there are a few cases where having an extra durable rope can be a good thing:

single skinny alpine lead ropes

big walls (more below)

a remote and longer trip where you need your lead rope to stay in good condition

Solution: a “Unicore” (aka “bonded sheath”) rope, created by the French company Beal around 2012, has the core and sheath glued together. With a Unicore rope, the sheath can get a cut, but the sheath does not separate from the core like with a kernmantle rope, and the rope (probably) remains still usable.

To use another anatomy example, think of it as how your skin is attached to the tissue underneath it.

Beal has a wide variety of ropes available with Unicore technology, from skinny alpine, to sport climbing, to burly big wall 10.5mm. (Some other manufacturers have their own version, such as the Maxim Platinum, Edelwiess Element, and the PMI Extreme Pro. (These companies mentioned Unicore technology, so I don't know if that's under license from Beal, or their own proprietary system.)

Especially for big wall climbing, you want ropes (lead and haul) that are as stout and abuse-resistant as possible. Your partner who's cleaning your pitch will especially appreciate your fine choice of rope, as, they jumar that single strand that’s loaded over an edge thousands of feet off the ground!

Also, in big wall climbing you're using ascenders with teeth on them, which can be especially hard on ropes.

With a Unicore rope, a small nick does not turn into catastrophic damage, so even if your rope does get slightly cut, you can (usually) continue to climb with it.

The Beal Top Gun Unicore 10.5 / 70 meter would be an excellent choice for your next big wall adventure.

For a more alpine mountaineering type rope, the 9.4 mm Beal Joker Unicore 9.1 would be a good choice. Finally, if you want one of the lightest single ropes available, check out the Beal Opera Unicore 8.5 (which I have and really like). Having the Unicore technology on a small diameter rope can boost your confidence when you see it loaded over an edge . . .

(Reminder: there are no affiliate marketing links or paid product promotions on Alpinesavvy. I’m writing about Unicore ropes because I think they're cool, and providing these links as a courtesy, not because I make many money off it.)

Here's a nice diagram from Beal and the American distributor Liberty Mountain. It shows a few other benefits: you can cut the end of the rope without it getting all fuzzy, it prevents the sheath from slipping, and there is much less water absorption.

image credit: http://libertymountainclimbing.blogspot.com/2013/02/the-real-truth-about-unicore.html

Video from Beal on some vicious rope abuse and impressive Unicore results. (Warning, viewer discretion is advised. =^)

Video from PMI with more rope abuse:

Block leading - don’t “trap” the leader

When climbing in blocks, where one person leads several pitches in a row, it's important to rig the anchor so the leader can easily unclip and continue. A good way to do this: use an extra locker to connect to the master point carabiner, rather than cloving directly to it.

When block leading, the same person leads several pitches in a row. (As opposed to swinging leads, when you alternate leads with your partner.)

Consider this anchor scenario (left photo): The leader arrives at the belay, and clips themselves directly to the master point carabiner (purple) with a clove hitch. Then, they put their second on belay with a Grigri, which is also clipped to the master point carabiner.

This is fine for swinging leads, but . . .

Can you see the (small) problem here when block leading?

How can you prevent the issue by rigging slightly differently?

Whoops, how is the leader going to remove that clove hitch without deconstructing most of the anchor? They can’t. (Ask me how I know this is a problem; I’ve done it!)

By cloving directly to the master carabiner, the leader has essentially “trapped” themselves. Even if they did clove themselves on the gate side instead of the spine side, they would still have to open the masterpoint carabiner, which is less than ideal.

When using a master point carabiner like this, it's good to think of it as being ‘“welded” closed; once it's shut, it doesn't get opened again until the anchor is completely broken down.

(Admittedly, this is a minor mistake and not a lethal one, but it’s annoying and usually takes a few unnecessary shenanigans to decluster it.)

A better rigging choice is shown on the right.

Here, the leader uses one extra locker to clove to the master carabiner. This allows them to easily unclip and continue to lead, without being trapped in the system, and without opening the master carabiner.

In most cases, clipping in like this with one extra locker is usually a better choice, because it gives you more options for general rigging and declustering unexpected situations.

For example, when you agreed to swing leads, but your partner arrives at the anchor and says “Hey, how about you keep on going, I’m tired . . .”

Other concerns, issues?

I know there are some anchor Polizei who are gonna get their feathers ruffled because the second is not belayed next to the spine of the carabiner. IMHO, it's nothing to worry about. The largest possible load when bringing up your second is going to be 2-3 kN; no possible way the carabiner could be damaged from that.

Concerned about three-way loading on the carabiner? It's fine. Carabiners loaded like this have been tested to break at about 17 kN, WAY more then you're ever gonna put on it and a recreational climbing context. Check out the photo below from Black Diamond.

Petzl Traxion pulleys - Micro vs Nano

The Petzl Traxion series of progress capture pulleys are an increasingly popular piece of gear. Let's have a closer look at the Micro and the Nano, learn some of their common functions, a few key differences, and some of the crafty things you can do with them.

The Traxion series of progress capture pulleys, made by Petzl, are an increasingly popular piece of gear. Let's have a closer look the two suitable for alpine climbing, the Micro Traxion and relatively new Nano Traxion.

Before we get into these, a word on the other two flavors of Traxion, the Mini and the Pro.

The red Mini Traxion is discontinued, but still available used. It’s a fine piece of gear for certain big wall applications, but it's too heavy for most alpine climbing.

The yellow/black Pro Traxion is popular with big wall climbers to pull up your haul bags, but it's way too big for the alpine world so we're not gonna cover it here. (If you get the Pro, be sure and get the newer model. It’s a big improvement over version 1.0.)

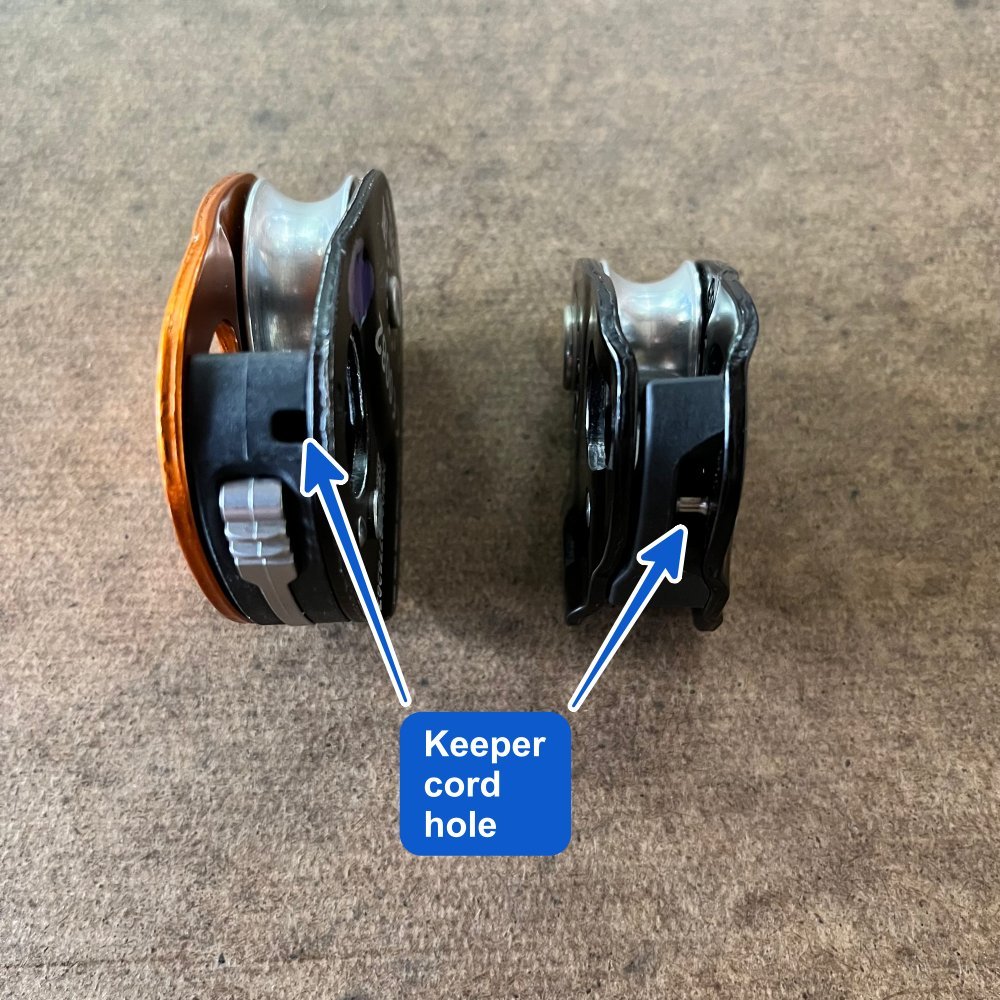

Micro and Nano Traxion: things in common

Both are rated 91% efficient. (Keep in mind that this “efficiency rating” is tested under optimal laboratory conditions, probably with a low stretch, small diameter rope. My “garage” testing of these devices with an older 8.5mm dynamic rope gives an efficiency of about 72% for the Nano, and about 76% for the Micro.)

Both have a way to attach a keeper cord. (This is obvious on the Nano, and harder to see on the Micro.)

Both work on frozen or muddy ropes.

Both can be used with the 6mm Petzl PURline and RADline static ropes. (This is maybe a little confusing, because the technical documentation for these devices says that 8mm (Micro) and 7mm (Nano) are the smallest diameter ropes allowed.)

Both are best used with a oval locker or HMS locker, not a D shaped locker.

Micro Traxion overview

Weight: 85 grams

Retail price: $130

Pass a locking carabiner sleeve through the clip point? YES

Retract and hold the toothed cam? YES

Rope size: 8 to 11 mm

Nano Traxion overview

Weight: 53 grams

Retail price: $100

Pass a locking carabiner sleeve through the clip point? NO

Retract and hold the toothed cam? NO

Rope size: 7 to 11 mm

Comes in stealth black =^)

Micro Traxion on left, Nano on right. Note the toothed cam is in the “locked open” on the Micro. Can’t lock open the cam on the Nano, but you can open the cam manually and hold it in place.

Both models have a spot to attach a keeper cord, if that’s your thing.

What can you do with a Traxion pulley?

Set up a drop C system for crevasse rescue, which gives you a 2:1 mechanical advantage, and puts the progress capture on the person in the hole, not on top.

Set up a “Z drag” system for crevasse rescue, which gives you a 3:1 mechanical advantage and perfect progress capture without futzing with a pulley and annoying friction hitches to hold the load.

Improvised rope ascending system, combine with a friction hitch or micro ascender like a Petzl Tibloc to go up a fixed rope.

Top Rope Soloing (TRS). One of the most popular applications for this device. (Nope, you won’t learn that on Alpinesavvy, Google is your amigo.)

Haul packs or lighter haul bags, with the Traxion on the anchor.

Set up a “far end haul” with a 2:1 mechanical advantage on the bag. (Nerdy big wallers only)

You can belay your second directly off the anchor with a Traxion pulley. But it's best to do it on relatively low angle snow or rock, where the chance of a fall is unlikely, and you’re keeping the rope snug on your second so any fall would not create very much force. With a load above about 4 kN you're gonna start to damage the sheath, as shown in the diagram below. If you choose to use the device this way, please be careful. Petzl has done solid testing on this, and has some major cautions . Read more here before you try this technique.

For putting multiple loads on the same carabiner, it's good practice to put the one receiving the largest load on the spine side of the carabiner. Typically if you're hauling, that's where the pulley should go. See diagram below.

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Pulleys/MICRO-TRAXION

image: https://www.petzl.com/INT/en/Professional/Choice-of-carabiners-for-hauling-systems-and-pulley-attachment?ProductName=MICRO-TRAXION

What's the best carabiner to use with a Traxion?

The Petzl website gives a bit of contradictory information about this. On one part of their website, they have a clear diagram that an oval or HMS locker is generally preferred, because it allows the pulley to sit in a more symmetrical position. However, in the technical documentation for the Sm’D carabiner, they have a diagram of that D-shaped carabiner being used with the Micro Traction. See diagrams below.

So . . . my read on that is that is: while pretty much any kind of locker is acceptable, you're probably gonna get slightly better results with an oval or, what I use, wide gate HMS belay locker.

image: https://www.petzl.com/INT/en/Professional/Choice-of-carabiners-for-hauling-systems-and-pulley-attachment?ProductName=MICRO-TRAXION

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Pulleys/MICRO-TRAXION

So, the key question: do you need one?

If you find yourself doing a lot of glacier travel or pack hauling, the answer might be yes. If you're doing more moderate snow climbing and rock climbing without much hauling, then the answer could be no.

This is an expensive item of specialized gear. If you're a beginning climber and building your rack, I suggest getting more commonly used gear first, and perhaps adding this later.

If you already have the Micro, I’d think most people would be pretty happy with this and not want to get the Nano.

If you don't have either, I'd probably recommend the Nano because it's less expensive and lighter and pretty much has the same functionality.

The always amazing Petzl website has a great series of tutorial articles on all the ways you can use this handy device. Read it here.

Finally, check out this short Instagram video that shows using the Mini Traxion for Tyrolean traverse, rope ascending, and large load 1:1 hauling.

(If the embedded video below breaks, you can try here.)

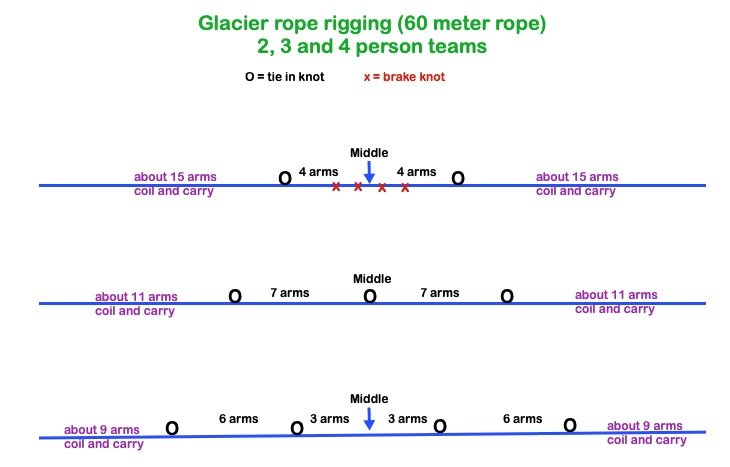

Rigging your rope for glacier travel

Here's a fast, clever and easy-to-remember way to ensure proper spacing between team members when traveling on a glacier. Plus, a diagram and photo to show actual distances for three and four person teams.

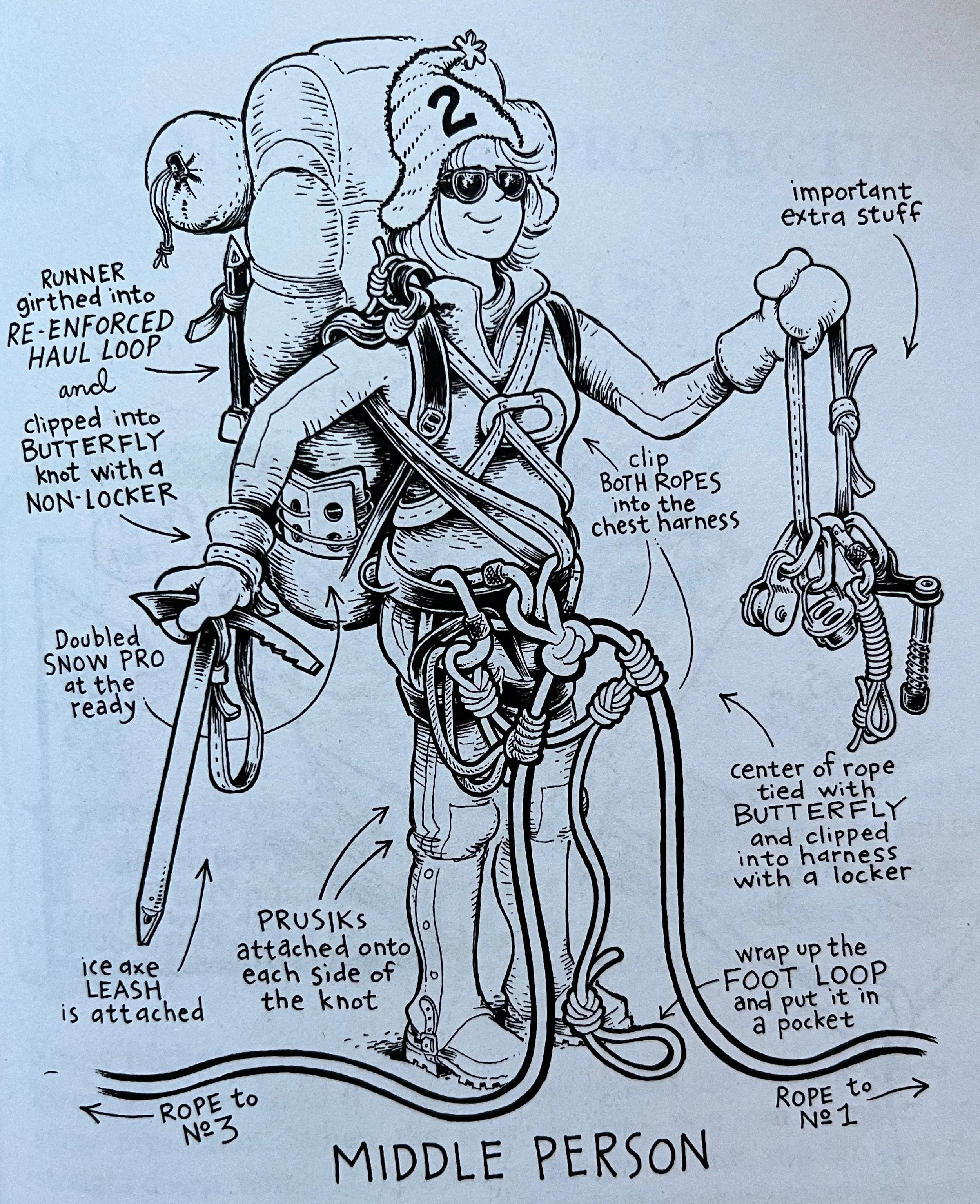

Image: from the highly recommended and hilarious book, “The Illustrated Guide to Glacier Travel and Crevasse Rescue, by Andy Tyson and Mike Clelland. Anyone setting foot on a glacier would do well to get this book. The method shown is a bit outdated, but it's still a great drawing!

(There are a few different book editions with different covers. They're all good, get whichever one you can.)

credit: Mike Clelland

I remember when I first learned crevasse rescue WayBackWhen, it was pretty darn simple. Two people tie to each end, one person ties to the middle, and off you go! 50 meter rope, 25 meters between everybody.

Turns out that has a few problems:

Communication can be difficult because people are further apart.

All the extra rope gets hung up on ice blobs and snow-sickles.

How do you do a rescue if the middle person falls in?

Happily we’ve moved into the modern era, where you climb a bit closer together (at least in my neighborhood, the Pacific Northwest), and the end people carry extra rope to initiate a rescue. But, that still leaves a few questions:

What distance should you have between climbers?

It sort of depends on the potential size of the crevasses you may be facing, but for moderate sized crevasses typical of the Pacific NW, here’s a quick and easy to remember how to set up the rope spacing. It varies a little bit, depending on the size of your team.

Take the number of people on your rope team, and subtract that from 10. That gives you the number of double “arm spans” between climbers

2 climbers: 10-2 = 8 - 8 arm spans of rope between climbers

3 climbers: 10-3 = 7 - 7 arm spans of rope between climbers

4 climbers: 10-4 = 6 - 6 arm spans of rope between climbers

Notes . . .

This is known in some circles as the “10 minus equation.”

If you’re on a two person team, it’s best practice to tie 4-5 brake knots in the rope between each climber. It's optional for 3 and 4 person teams, but if the terrain is hairy then go ahead and tie some.

Generally, you want to put the least experienced person(s) in the middle, and the two more experienced/skilled people on the end. The end people will be more responsible for route finding and probably initiating a rescue if you need one.

Note - there are lots of different ways to rig your rope team for glacier travel. This is one of many that works. In areas with larger crevasses, like Alaska and the Himalaya, you’d probably want more distance between people than what I’m describing here.

Pro tip: If you're doing an alpine start, rig your your rope with knots and coils the night before. It's one less thing to do at 0:dark:30 by headlamp when you're sleepy.

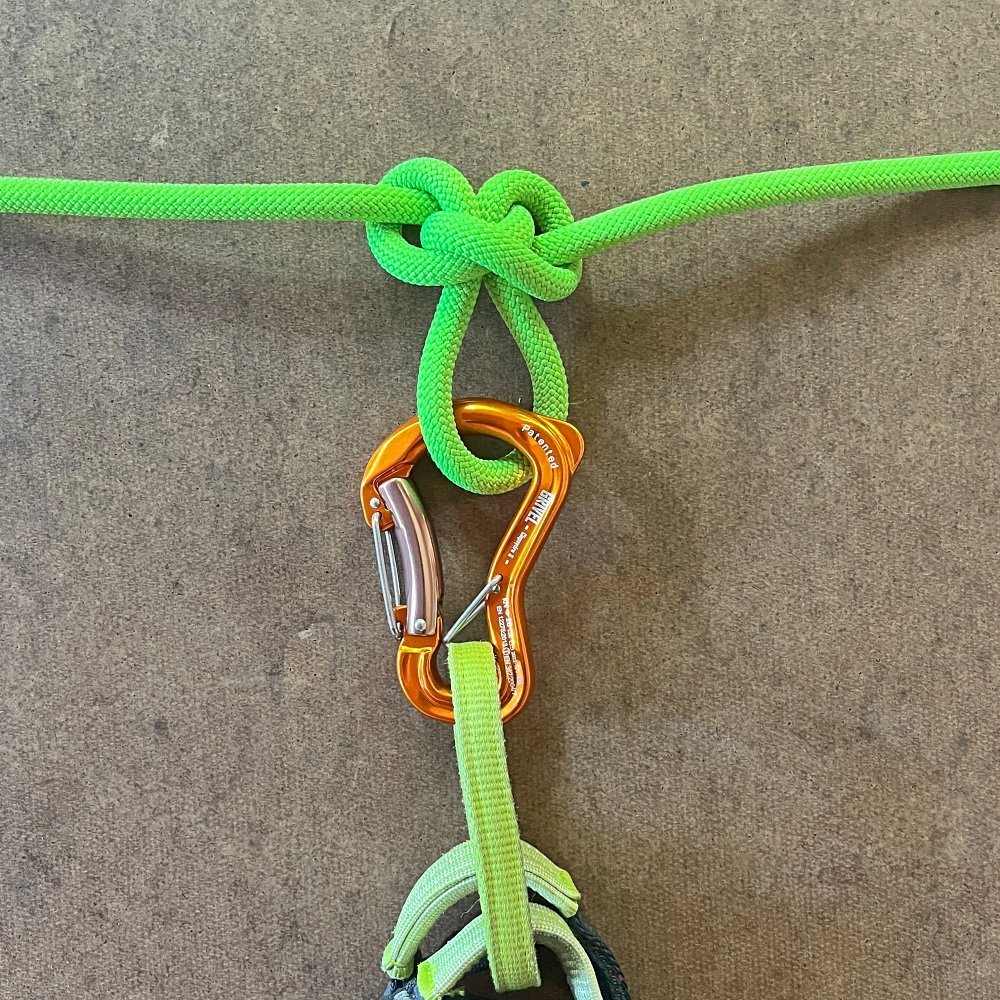

Generally, it's best practice to have all team members clip to a knot with a locking carabiner, rather than tying the rope through the harness. Doing this allows you to unclip from the rope more easily, which is convenient when performing a rescue.

The end people need a good way to secure the extra rope. Some people advocate stuffing it in your pack. Bad idea, because every time you want to get in and out of your pack you have lots of annoying rope coils. Much better is to secure the rope in a small butterfly coil, I like to secure the coil with a Voile ski strap. Yes, I know how to tie off a butterfly coil, but using a ski strap is faster and easier. I don’t like the coils around my neck unless there’s a good reason to do so, like moving from glacier to rock, where you need to take in coils and walk close together.

The standard approach to clipping to the rope is to use two carabiners, opposite and opposed usually with at least one a locker. Here's my alternative, using the odd-looking Grivel Clepsydra S carabiner. It has a wire clippy thing so it can never be cross loaded, and it has a double gate that will never freeze shut or wiggle open during a day of tromping around on the glacier. It's my new favorite.

A team of two can require a longer rope (60 meter minimum) than a team of three or even four.

Yes, this is a little counterintuitive! If you're using the modern standard of a drop loop C, that means you need about twice the distance between climbers at a minimum for a typical rescue. A party of three or four will ideally build an anchor at the closest team member to the fallen person. This allows them to use the rope between the other team members for the drop loop and thus they can carry fewer rescue coils on each end. A team of two is probably not able to do this.

This means that it's best practice for a two person team to be on a 60 meter rope at a minimum, while a three person or four person team can probably use a 50 meter rope.

Check out the below diagram for a two person team. With 8 arms spans between climbers, and with 4 brake knots which each take about 1 meter, that leaves just 15 meters in rescue coils for each person to carry.

The good news is, if your drop loop turns out to be a little bit short, it's easy to extend it with whatever extra slings, cordelettes, etc. you might have available. This means that a two person team does NOT always need to carry twice the amount of rope between climbers. (Another alternative for a two person team with a shorter rope is that they do not use a drop C and instead use a drop end 3:1, which comes with its own set of problems and benefits. Here's a detailed article on this technique.

Either way, the bigger picture, if you’re a two person team in serious crevasse terrain, you absolutely have to have your systems dialed and be completely self-sufficient to perform a rescue. Two person glacier travel is recommended for experts only.

Rope rigging for a THREE person team (with at least two experienced climbers):

Find the middle of the rope, tie a butterfly knot for the middle person.

Measure about seven full arm spans from this middle knot towards one end, and tie a butterfly knot. Repat for the other half of the rope. These are the clip in points for the two end people. The end people coil the remaining rope for use in a possible rescue.

If you have only one experienced person on your rope team, then the novices should probably clip in starting at one end of the rope with seven arm spans between them, and the more experienced person should carry all the the remaining rope. Let’s hope they don’t fall in . . .

Rope rigging for a FOUR person team:

Find the middle of the rope.

Measure three arm spans to the right of the rope middle, and tie a butterfly knot.

Measure three arm spans to the left of the rope middle, and tie another butterfly knot.

Finally, measure six arm spans from each of these knots toward end of the rope, and tie your final two butterfly knots for the end climbers. Again, the two end climbers should ideally be more experienced people capable of route finding and crevasse rescue. They also carry the remaining rope, either coiled over their shoulder or stuffed into a backpack.

Distance wise, this works out to be about 10 meters between climbers.

(Note the orange Voile ski strap securing the coils for the climber on the right, a quick and secure way to tame extra rope.)

Check out the nice video from AMGA Guide Jeff Ward to see how this works.

DIY tether with the Kong Slyde

Tethers are not for everyone, but many people find their instant adjustability to be handy in lots of different climbing situations. Some of the more specialized ones can be quite expensive. Here's a low cost DIY version, using the cleverly designed Kong Slyde.

Kong Slyde + 2 meters of rope = low cost adjustable tether.

This clever device works much the same as the Petzl Adjust tethers, but costs a lot less, around $12. Kong has it in the “aid climbing” category on their website, but I think it’s better as a personal tether.

Note:

Not all carabiners fit in the Kong Slyde. Some wider D shaped lockers may not fit. Here I’m using the Petzl Sm’D twistlock, which fits great and has a twistlock for extra security.

8.5-ish to 9ish mm dynamic rope is the best choice for this. Anything smaller the strands can invert and the Slyde fails! Much bigger and it’s really hard to pull the rope through. Dynamic is good because, ya know, it stretches.

My friend Ryan at HotNOT2.com tested different rope flavors, and he likes the Beal 9.1 mm Joker rope for smoothness and adjustability. Buy that rope by the foot, along with the Slyde, at his sweet online gear store.

You can buy rope by the foot from Arbsession. Arbsession can add custom sewn eye splices into your rope, which could be nice. I have not tested this rope myself with the Slyde, but the diameter looks about right.

Two meters of rope will give you a tether that's probably a bit on the long side, but that's better than having it too short. Feel free to trim it down if needed after testing. For me, I'm about 5’ 10” / 180 cm, and these measurements work for me. If you're much taller, you probably want to add a bit more rope.

Start with 2 meters of 8.5mm or 9mm rope.

In the tail end of the cord, tie a stopper knot. Cinch it down well. I took the extra step of securing it with a zip tie so it can never come undone.

Correctly thread the cord into the Slyde, see photo below.

In the other end, tie an overhand on a bight, with a loop that's just big enough to girth hitch through your belay loop. Dress and cinch down the knot. Done!

To extend the Slyde, grab it with your palm down, and the rounded end of the Slyde pointing toward you. Tilt your hand up and push forward, and the Slyde should extend. Little hard to describe, watch the short video clip below. Practice and you’ll get the hang of it.

Check out this short video on using it.

Rope ascending with the Petzl Traxion

The Petzl Traxion is a handy device for many different climbing situations, including ascending a rope. Here are a few different ways to set it up.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

The Tibloc micro ascender and the Traxion progress capture pulley are a pair of versatile tools from Petzl that are handy in a variety of self-rescue scenarios.

They work especially well for those (hopefully rare) times when you unexpectedly might have to ascend a rope (working WAY better than a trasditional prisik / friction hitch.)

Important:

When ascending a rope with any kind of toothed device like this, keep the rope tight between you and the anchor at all times. Do not allow slack rope between you and the anchor. A fall or slip with even a tiny amount of slack rope can generate enough force to damage the rope. Petzl has done some sobering studies on this, read them here.

The Tibloc has a reputation as being hard on ropes. Using a rounded stock locking carabiner, and not suddenly weighting the device, can help minimize this.

With both of these methods, you need two points of connection to the rope (your tie in knot doesn’t count). Never rely on just one ascender. A failure may happen for one of three reasons: the ascender comes off of the rope, the ascender fails to properly grab the rope (mud, ice, etc) and your tether carabiner can become unclipped. The simplest backup: Every 5 meters or so, tie a overhand on a bight and clip it to your belay loop with a locker. (More often if you’re scared.)

As mentioned above, definitely practice with this in a controlled environment close to the ground before you ever try it for real!

Let's look at three different methods. If you have this gear, try them both and see which one works for you. (The standard figure 8 tie knot is omitted for clarity.)

Tips:

Think of rope ascending as a “movement sandwich.“ That’s a short movement of exertion, in between two periods of rest. Rest > move > rest. Rest > move > rest. Use your legs. If your arms are getting pumped, you’re probably doing something wrong.

What carabiner to use? With both devices, a wide gate HMS belay carabiner (or oval locker, if you have one) is usually the better choice, as it aligns the load better. A “D” locking carabiner is acceptable.

Method 1: Traxion attached to your harness, Tibloc is the foot loop

Sequence:

Girth hitch a 60 cm sing to your belay loop.

Put Traxion on rope, with teeth facing down.

Clip the sling to it with a locker.

Next . . .

Clip the Tibloc to the rope below the Traxion.

Clip a 120 cm sling, this is your foot loop.

To climb the rope: Put your weight on the Traxion. Push the Tibloc as far up the rope as you can. Bend your foot under your butt, stand up in the foot loop, and simultaneously slide the Traxion up the rope. Sit back on the Traxion to rest. Repeat as necessary.

Tie a backup bight knot and clip to harness every 5 meters or so.

Method 2: Tibloc as a foot loop, Traxion attached to your harness

Sequence:

Clip Tibloc to rope. (if you don't have a Tibloc, you could use a cordelette tied in a friction hitch shortened with an overhand knot for your foot.)

Clip a 120 cm sling to the Tibloc; this is your foot loop.

Put Traxion on rope, and clip to your belay loop. (Clip the Traxion “Teeth toward Toes”, i.e., teeth pointing down.)

To climb the rope: slide the Tibloc up the rope as far as you can, bend your foot under your butt, stand up in the sling, and simultaneously pull any slack rope through the Traxion.

Tie a backup bight knot and clip to harness every 5 meters or so.

From the (always awesome) Petzl website. It looks like this diagram shows an extra backup sling running from the Tibloc to the harness. That's another way to do it if you don't want to tie backup knots, as this provides a second point of connection to the rope.

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Pulleys/MICRO-TRAXION

Method 3: Traxion as a foot loop, Grigri as progress capture

If you have a Grigri, you can use that is the progress capture.

Sequence:

Clip Traxion to rope, with teeth facing down.

Clip a 120 cm sling to the Tibloc; this is your foot loop.

Put Grigri on rope, and clip to your belay loop. Be sure the rope is fed correctly.

To climb the rope: slide the Traxion up the rope as far as you can, bend your foot under your butt, stand up in the sling, and simultaneously pull any slack rope through the Grigri.

Tie a backup bight knot and clip to harness every 5 meters or so.

And finally, if you're on low angle terrain and maybe want to bend a few safety rules, you could clip a Traxion to a fixed rope, clip it to your harness with a 60 cm sling, and use the carabiner /device to pretty much Batman up the rope.

Check out this Instagram video that shows an IFMGA Guide demonstrating this (pretty-darn-fast-but-probably-not-approved-by-Petzl) method.

Where do you carry your satcom device?

A satellite communication device can be a critical tool in managing a backcountry emergency. A pretty simple question: should you carry it inside or outside the pack? Here's a pretty comprehensive list of pros and cons for both approaches, along with my preference.

A satellite communication device, such as the Garmin inReach, or the one I prefer, the ZOLEO, are increasingly popular for backcountry users (and pretty much mandatory for guides).

What sounds like a fairly simple question: where do you carry it? There aren’t many options.

Inside your pack

Outside your pack, clipped to a shoulder strap

Outside your pack, in a pocket of your clothing or maybe in a padded pocket on a pack strap

If you have a device like this, what's your preference?

To a certain extent this is a pedantic question. In the bigger picture probably doesn’t matter too much. Everyone can do what they want, “Hike Your Own Hike”, blah blah blah. However, I’m coming at this from the point of view of a climber, where there is almost always a range of best practices, and not so much as a hiker, where personal choices like this ultimately may not matter very much.

I have my preference, but I have no agenda to convince people to do it. With this article, I simply want folks to think through what they're doing and realize the pros and cons to different approaches.

(Here, we're talking about a device that's only for emergency comms, and not for GPS navigation. If using any device for actual navigation, you almost always want to have it outside the pack and accessible.)

Reasons for storing a satcom device INSIDE the pack (my preference):

In a nutshell: Security is more important than accessibility.

Why clip an expensive and potentially mission-critical piece of equipment on the outside of the pack, where it has a much higher likelihood of getting damaged or lost? You don’t clip your iPhone to a backpack strap, why would you do this for a satcom device?

I’ve asked many mountain guides and search and rescue professionals this question. Every single one of them says they keep it on the inside of their pack or maybe in a pocket, never on the backpack strap. What does that tell you?

The fewer things clipped to and jangling around on the outside of your pack, the better.

You're going out in a group and at least one other person has one, so the reason for immediate accessibility decreases.

My device, the ZOLEO, maintains satellite connectivity just fine when it’s inside my pack, including sending location pings at preset intervals.

If you do take a fall, it gets ripped off of your pack, you're injured and you really need it, you may not have access to it.

Reasons for carrying a satcom device OUTSIDE the pack (on a shoulder strap):

(Not my imagination, I've heard these reasons from other people.)

You feel the need for immediate access to the device, no matter how unlikely that situation might be, outweighs potentially losing it or damaging it. (This sentiment seems more common for solo hikers.)

If you’re using it for texting a lot, if you have it on the outside of your pack, you can more easily hear the chirp of an incoming text. (For me, sending non-critical texts is the last thing I want to do when I’m in the backcountry, so this is not an issue for me, but it might be for you.)

If you're using it to send check-in (“all is well”) messages, it's easier to grab it off your pack and send one on-the-go than potentially forgetting to do so after you get to camp.

You've seen pictures in social media or ads about satcom devices clipped to pack straps, and so you think that's how it should be done. (I think it’s a subtle marketing ploy by the satcom companies to indirectly encourage the pack strap. Looks better in social media, and free advertising for their device. Not much of that happening if it can’t be seen inside your pack.)

The devices come with a handy little square shaped carabiner, which seems designed to clip onto the flat webbing backpack strap.

To show potential hostile people that you have one, which will hopefully deter any sort of a threat.

If you're in an emergency situation and you get adrenaline-fueled brain malfunction, having it on the outside of your pack might remind you or your partner that you actually have one and you can use it. (Don't laugh, this happened to a friend of mine in a canyoning accident. One of them had a satcom device and they had to deal with a serious accident for a LONG time before they remembered that they had the device.)

“I can get to it more easily in a crazy catastrophe, where I might not be able to get into my pack”. Yes, I can see this might be true if you’re in some sort of boating accident, like ‘man overboard’ in the middle of the ocean or something. But realistically, what’s the scenario when this could happen if you’re hiking or climbing? You could probably come up with some crazy contrived scenario, but if it's a 1 in 100,000 chance of happening, why are you even concerned about it? If you’re so severely injured that you can’t unzip a pocket of your backpack, you’re probably not gonna stay alive long enough for search and rescue to be much help anyway.

One scary story: a PCT backpacker attempted a sketchy river crossing at high water. They were pushed off their feet, ditched their backpack to swim safely to shore, lost their pack, and were then in a serious situation. (This person did NOT have a sat com device). Yes that would suck, but c’mon, how often does something like that happen? If you were in that situation, perhaps you might have the foresight to remove your satcom device from your pack before you did something sketchy and attach it to your body?

If you’re unconscious out in the woods and someone else walks by and finds you, they might see the device on the outside of my pack, hopefully know how to properly use it, and call for help. I suppose that's remotely possible, but extremely unlikely. With logic like that, you’d carry your first aid kit dangling around on the outside of your pack, but no one does that.

So, that pretty much summarizes the pros and cons for both approaches. Like I said, ultimately the more important thing is probably that you have one and know how to use it, either to assist yourself or someone else. If you have some other reasons, feel free to email them to me and I'll consider adding them to this article.

The far end haul, explained

The far end haul is a #CraftyRopeTrick that sets up a redirected 2:1 mechanical advantage haul that happens at the load end of the rope, not at the anchor end of the rope. The far end haul is used in big wall climbing, and can be handy for self rescue. Plus, it's just plain fun to set up to see how it works!

The far end haul haul for big wall applications is generally attributed to Chongo, a legendary Yosemite dirtbag who was famous for extended vertical camping trips on El Capitan with ridiculously large loads.

Having a Petzl Traxion (or similar progress capture pulley) on the load also lets you set up what’s called a “far end haul”, which at first seems like some sort of sorcery. (This load can be you, or another person pack, haul bag etc.)

Usually, hauling happens from the top end of the rope next to the anchor. However, with the far end haul, you to lift your load with a theoretical 2:1 mechanical advantage (MA) by pulling on the “far end” of the rope next to the load, rather than from the primary anchor.

This rig can be useful for big wall soloing / hauling. If you’re hauling your bag from the top, and it gets stuck, you can rap down to it, lift up a little bit by setting up a 2:1 MA with an ascender and a pulley, and free the bags.

I learned from a caver that this is also called a “traveling haul”, used in rescue to raise someone up a large drop. (Hope I never have to do that!)

It also has some self-rescue applications, and can be really helpful for moving your bags around at the anchor, see video below.

To rig the far end 2:1, clip an ascender (or a prusik if you’re short on gear) on the loaded strand of the haul rope, clip a carabiner with a pulley onto the ascender, and pull down on this redirect. Your bodyweight should lift the bags with this theoretical 2:1 MA and the micro traxion will “climb” up the rope and capture your pulling progress, sweet!

In the photo below I'm using a handled ascender. You could use any kind of ascender here like a Tibloc, a second Micro Traxion, Ropeman, etc. The pulley is optional, but definitely helps increase your efficiency when pulling.

Note the real mechanical advantage you will have in the real world when you try this. Below are pull test results with a 10 lb weight from another Alpinesavvy post, mechanical advantage in the real world. You can see that about the best you can do with the far end haul pulley is 1.3 to 1. And if you don’t have a pulley, you probably shouldn't even bother putting the redirect through a carabiner, as the mechanical advantage falls below 1:1. (Note, DMM Revolver carabiners don’t really do anything to reduce friction over a regular carabiner, avoid using those.)

But, even if you’re not soloing, it has a few advantages.

The far end haul can minimize rope abrasion, because the haul rope doesn’t move.

If you have to haul from a point or over a ledge with a LOT of rope friction, you can instead far end haul and have zero friction.

You can easily move the bags around at the anchor; more below.

Here’s a video by wall ace Mark Hudon who shows exactly how to do this. Rather ingenious, no?

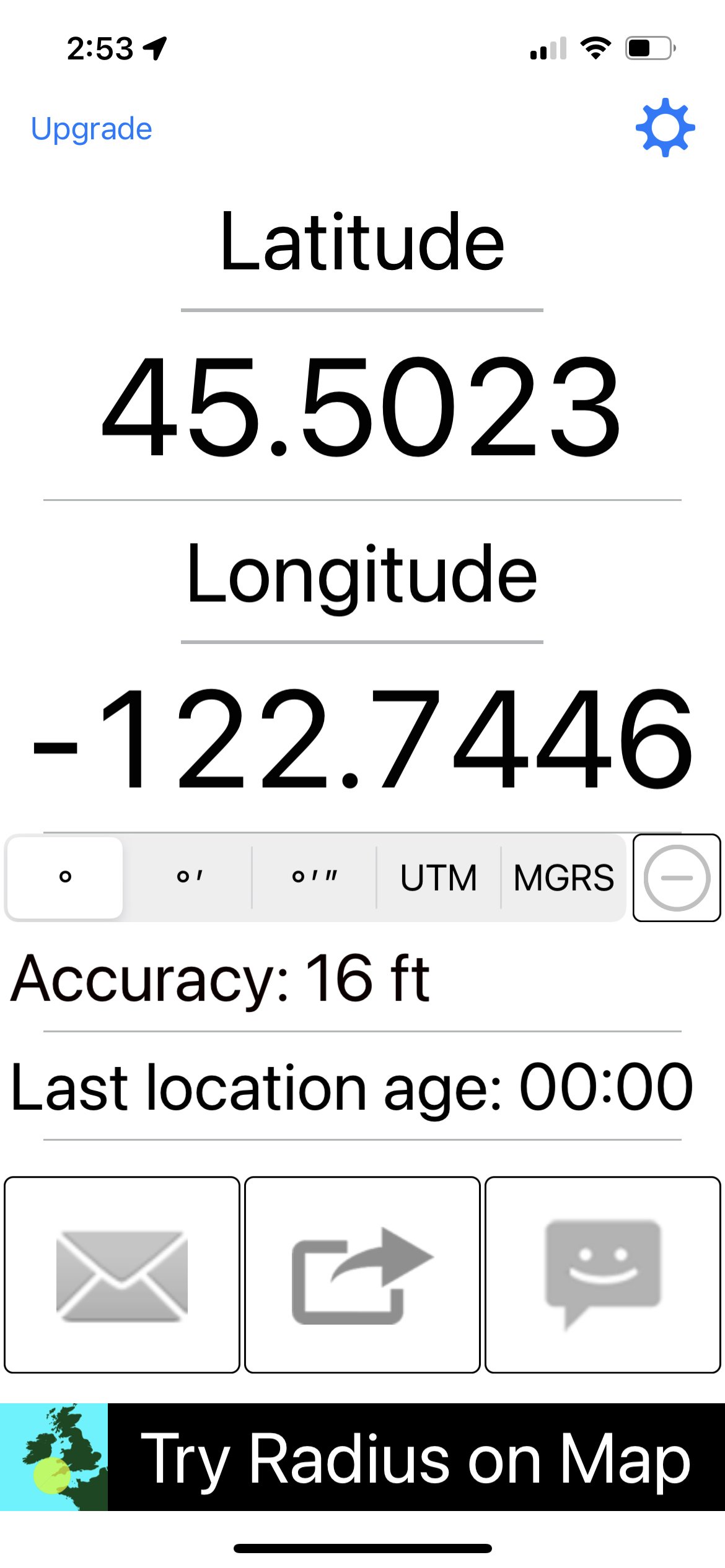

9 phone apps for wilderness navigation

There are lots of handy tools you can keep on your phone to help with wilderness navigation. Here are some of my favorites. Better yet, pretty much all of them are free and weigh 0.0 grams!

There are lots of handy tools you can keep on your phone to help stay found. Here are some of my favorites.

Better yet, pretty much all of them are free and weigh 0.00 grams! (This is geared toward iPhone, ‘cuz that’s what I have.)

In rough order of importance:

GPS - GaiaGPS, Caltopo and Fatmap are all popular options. Find one, learn it. Cost, about $20 a year.

Compass - The iPhone has a great built-in compass. Cost, free.

Altimeter -There are lots of altimeter apps. Cost, free.

Photos - Take photos of guidebook pages. Download a photo of a redlined route, save it to your phone. Take photos of your route when climbing, red line or annotate. Save Google Earth screengrabs. Cost, free.

Kindle / pdf reader - Save a PDF of a map. Download an entire guidebook (or wilderness first aid book!) as an e-book. Cost, free.

Inclinometer - The iPhone has a handy inclinometer, under the “Measure” tool. Great for assessing avalanche potential and bragging to your friends about how steep your ski slope was.

Show & share my coordinates - clearly display your coordinates, email or text them along with a message. Extremely helpful to show your exact location if you have a backcountry emergency and a cell connection. This is one of several ways to get coordinates from your phone. This app is called “My GPS Coordinates”. Cost, free.

Barometer - Newer phones have barometric pressure sensors. Rising or falling barometric pressure can indicate a potential change in weather. Cost, free.

GPS Diagnostics - kind of nerdy, but occasionally useful. If your GPS is acting up, you can use this to see the quality of your satellite connectivity. Cost, free

GaiaGPS

Compass

Altimeter

Photos

Screen grab from web, Google Earth screen grab, guidebook photo

Kindle / Book reading app / PDF reader

Make a PDF map in CalTopo. Email it to yourself or AirDrop to your phone. Save in Books or Kindle.

Inclinometer

Show & share my coordinates

(Tip - you only need 4 decimal places.)

Barometer

GPS Diagnostics

Mobile phone SOS texting via satellite

Big news for emergency backcountry communication: As of Nov 2022, iPhone 14 users in North America can send an SOS text via satellite, no cell coverage or extra hardware required. Expect expansion to other countries, other phones and expanded services soon, this is huge.

As of Nov 15 2022, you can send an emergency text (in the US and Canada) on an iPhone 14 via satellite - no cell coverage required. If you’re outside cell coverage and run your car into a snowbank, crash your mountain bike, have a climbing accident, or simply get lost, your potential epic may have a MUCH better ending.

You knew it was coming; I've been predicting and waiting for this advance for a long time. It’s starting with Apple, and it's very likely Android will soon follow. This is a great use of technology that will definitely save lives, and will surely be welcomed by Search and Rescue (SAR) teams.

Map of cell phone coverage from all carriers in the western United States, (from a GaiaGPS screen grab)

You can see substantial portions of Nevada, Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Colorado Rockies, Oregon and Washington Cascades, and the California Sierra lack cell coverage. That's where most of the fun is!

image: GaiaGPS screen grab

Apple iPhone 14

Here's how it works:

This service is for emergency communications only, and not for normal calls, texts, or data.

To begin, dial 911. If you can't be connected through the cell network, satellite connectivity is initiated.

For best results, you need to point your phone toward a satellite in the sky. Your phone walks you through this. Having a clear view of the sky and minimal tree cover is best.

There are some programmed screens that walk you through the process of requesting emergency help, check the screen grabs above.

Very cool: There's even a demonstration mode, so you can practice going through all the steps before you (hopefully never) use it for real. This demo mode uses real satellite connectivity so you can see how it works in real time. Settings > Emergency SOS > Try Demo.

If you have a predefined emergency contact on your phone, that person can also be notified, and be included in the ongoing text chain between you and 911. (Settings > > Emergency SOS > Set Up Emergency Contacts in Health > Create Medical ID). Check the last box for “Share During Emergency Call.”

If you're in an area where emergency services can receive text messages, the text message will be sent directly, otherwise it will go to a relay center with Apple-trained specialists that will be able to place an emergency call for you. (Note that many 911 call centers in the United States can’t receive text messages directly; I know, that’s pretty sad . . .)

If you don’t have an emergency, you can share your location through the “Find My” function to show others where you are. This could be used similar to the “Here’s my coordinates, everything‘s OK” check in function that comes with standalone satcom devices.) See photo below.

This service will be free for two years, and then Apple will probably start charging some sort of subscription fee.

Starting December 2022, this service will be available to certain European countries - France, the UK, Ireland, and Germany. (Expect the rest of Europe to soon follow.)

Apple says the service might not work in places above 62° latitude, such as northern parts of Canada and Alaska.

Globalstar is Apple's satellite operator.

Read more: Detailed explainer article

Here's a photo of how you can share your location via satellite in a non-emergency. This could be used as a daily check-in with concerned folks at home, for example.

image: https://www.dcrainmaker.com/2022/11/apple-iphone-satellite-sos-emergency-explainer.html/amp

Here's a nice video that shows the process.

T-Mobile and Starlink . . . someday

In August 2022, T-Mobile announced a partnership with Starlink. Starting with the next generation of Starlink satellites, to be launched next year, T-Mobile 5G service will include satellite text messaging.

Now, if this was just Elon Musk tossing out his latest dream-of-the-future that’d be one thing. But it was announced at a major T-Mobile promotional event, so I’d like to think that carries a little more weight.

Here’s a summary of how it’s supposed to work, as best as I can piece together from several web articles:

T-Mobile’s “vision” is for it to be included for free in the carrier’s “most popular plans.”

For lower cost data plans, some sort of monthly service fee will probably apply.

Two way text messaging is offered initially. Voice and limited data may come later.

Service will be “everywhere in the continental US, Hawaii, parts of Alaska, Puerto Rico and territorial waters.”

Your current phone can use the satellites, no additional hardware required.

T-Mobile says, “There may also be a considerable delay of half an hour or so until the message is sent or received.” (Whoops, that doesn't sound so good.)

Anticipated timeframe: mid 2023

Read more: T-Mobile website

Sounds like if you have an iPhone 14 and your carrier is T-Mobile, you might have access to both of these options?

Whether or not you choose to switch to T-Mobile, love or hate Elon Musk, or don’t want to upgrade to the latest iPhone, I think we can all agree that this is a great use of technology that will absolutely save lives.

What if you already own a dedicated satcom device, such as a Garmin inReach, or my favorite, the ZOLEO?

That probably depends on the remoteness of your trips, how long you stay out, the potential risk of your activities, and what your texting needs are.

The iPhone is (for now) geared towards emergency communications only.

If you . . .

have anxious loved ones at home who want a daily check-in text that “all is well”

park your camper van/truck in the boonies for a week and need to stay in touch

are a social media star and want to post to your fans from your latest through hike or expedition

need weather forecasts in remote areas

Then may want to hang onto your satcom device.

However, most everybody else will probably choose their phone. Doing this avoids carrying an extra unnecessary device, and saves you $$$ - the initial several hundred dollar cost of a satcom device, plus the monthly subscription fees (which can definitely add up). I think all data carriers and phone manufacturers will offer a similar service in the next few years, this is just the initial wave.

If I were the head of Garmin or Zoleo, I’d be a pretty nervous right now. Finding yourself suddenly competing with Apple and Elon is generally not a good thing.

How to use the Beal rope marker

A middle mark on your rope is very important, for both setting up rappels and for safe lowering from one pitch routes. Yes, you can probably use a Sharpie pen, but an easier and longer lasting option is the Beal rope marker. Here are a few tips how to use it, including the not so obvious way to open the bottle.

Most quality ropes these days come with a middle mark from the manufacturer. But . . .

Some don’t

Even if yours did, it can fade over time.

Why is a middle mark important?

It helps you set up your rappel more quickly and safely.

Short rope warning. If you’re single pitch climbing and the belayer notices the middle mark passing through their belay device BEFORE the climber has reached the anchors and plans to lower off, that’s an immediate sign that your rope is too short! STOP, get creative, and next time, bring a longer rope and RFG (Read the Friggin’ Guidebook).

(Hopefully you know the importance of using a closed rope system, which means the ends of the rope are always tied either with a stopper knot or into someone's harness to prevent dropping your partner when lowering or rappelling off the ends of the rope, two of the most common climbing accidents.)

Even if you have a “bi-pattern” rope with a sheath color or pattern that changes in the middle, it can still be a good idea to mark it. Most bi-pattern ropes are extremely obvious, but some are more subtle. Depending on the color and pattern, the change can be hard to see in low light or with a headlamp (ask me how I know this.)

There's been a L O N G debate on the interwebs about the safety of using things like Sharpie pens and laundry markers to mark the middle. We’re not going to rehash those here.

One solution that most people should be comfortable with: go with a recommended product from one of the largest rope manufacturers in the world. The French company Beal offers a rope marker that has a specially formulated ink in a handy dispenser that's designed for use on climbing ropes.

The Beal rope marker is approved by Beal, Edelweiss, Blue Water, Roca, PMI, New England, and Lanex. There are some big names here that are not mentioned: Mammut, Edelrid, and Sterling, to name a few. If you have one of these other ropes, you may want to contact the manufacturer and see if this marker is approved.

(Another option is the rope marking pen from Black Diamond.)

As far as I know, there has never ever been a case of a climbing rope breaking because of some aftermarket middle mark. But there have been dozens of cases of people rappelling off the ends of the ropes, or dropping their partners when lowering because their rope was too short. Let's focus on a solution to the real problem and not invent imaginary ones.

A few tips . . .

Before you start, recommended items are: 1) exam gloves to protect your hands, 2) tape to make a clean line, and 3) something to protect your work surface (like cardboard) from the ink. Do NOT do this on your kitchen table! I suggest working outside. It’s gonna be messy.

To unscrew the dispenser cap, you turn it CLOCKWISE, not counterclockwise. (Silly me, I almost broke the bottle turning it the wrong way.)

Remove the stopper, screw the dispenser cap back on (counterclockwise!) and roll the ink onto your rope. Let it dry, ideally in a well-ventilated ideally outside place for a couple of hours. Done, give yourself a high five.

You have enough ink to do many ropes, invite your friends over.

I've marked a lot of ropes with Sharpie pens, and this Beal marker works much better.

Here's a short video showing the process.

Stick clip a preplaced quickdraw with the double loop slipknot

Do you need to clip a “project” quickdraw that’s already on a bolt? If you have a long stick and know how to tie this crafty double slipknot, it’s easy. Check out the article and video to learn how.

Do you need to clip a “project” quick draw that’s already on a bolt?

Provided you have a stick or something similar that can reach the bolt, and you know how to tie this crafty double slipknot, it’s easy.

From your tie in, pull at least enough rope to get from you to the first bolt.

Tie a double loop slipknot. (Yes, this is probably a new knot, but you’ll probably learn it after a couple of tries; watch the video below)

Put one of the two loops into a stick, trekking pole, or something similar, and tighten that loop down.

Push the stick up, and carefully slide the other open loop around the bottom carabiner of your quick draw.

Pull on the strand of rope going to the loop around the quick draw.

That slipknot will close and snap into the carabiner. Schweeeet, you’re clipped! Magic!

Pull down on the stick, and pull on the other strand of rope.

This should release the other half of the slipknot. If you did it right, voilà your rope is now in the draw with no knots in the rope.

Get a well-earned high five from your partner for knowing this crafty rope trick. 😀

It’s a better show than a tell, watch the video below.

Haul bag rigging 101

There are lots of different approaches for rigging your big wall haul bags. Some old school methods still work pretty well, but there are a few more modern approaches that might make things a lot easier.

Thanks to big wall ace Quinn Hatfield @sprint_chef for the “connect two bags with quick links” tip near the bottom of this page.

A few words on hauling, from big wall expert Andy Kirkpatrick:

“Hauling is potentially one of the most dangerous aspects of big wall climbing. This translates to ultra-caution in all parts of your hauling system and interaction with bags, haul lines, docking cords, and pulleys. If you rush and make a mistake, drop a load or have it shift where it's not wanted, you could easily kill someone or yourself. I try and teach climbers to view their bags as dangerous creatures, like a great white shark, rhino, or raptor that is in their charge. The ability to keep them calm and under your control comes down to paranoia, foresight, and heavy respect for the damage they can do.”

There are MANY different ways to set up your bags for hauling. While some traditional methods have served big wall climbers fairly well for a long time, there are some more modern approaches that may make your life a lot easier. Try these different systems, and see what works well for you!

A more traditional / old school hauling setup looks something like this:

Cut off plastic bottle as a knot protector (lifted up here for the photo, in practice you slide the bottle down over the knot)

No swivel

End of haul rope tied directly to master hauling carabiner

Carabiner connects the short strap to the master point carabiner

Bag clipped to anchor with a sewn pocket daisy chain

old school haul setup

Let's look at a few potential issues with this set up.

Nothing really wrong with the plastic bottle. (Sidenote, big wall expert Andy Kirkpatrick suggests using an oil funnel from a car parts store instead of a plastic bottle. The oil funnel has a long, tapered neck that can allow it to slide past obstructions more easily. I haven't tried it but it sounds sensible.)

No swivel. A swivel is somewhat optional and costs a bit, but can definitely save your bags from twisting your rope.

End of rope tied directly to master carabiner. Again, nothing really wrong with this, but if you need to lower out your bags you're going to need an entirely separate rope to do so.

That red carabiner connecting the short haul bag strap to the master carabiner? That can be a BIG hassle with a heavy bag when the master haul carabiner is loaded, because you have to pretty much lift the weight of the bag and have one hand free every time you want to clip or unclip. There are much better ways to attach these two straps.

Finally, that evil sewn pocket daisy chain! That sucker can be very difficult to unclip, especially if the pitch above is traversing. Much better practice is to use a releasable docking cord, more on that below.

Here’s a more modern way to rig your haul bag.

A progress capture pulley such as a Petzl Traxion is attached to the haul bag, not a bight knot. Yes, you haul directly from the pulley. No, it doesn't damage the rope. The pulley gives you a lot more flexibility. You can lift up on the bags with a 2:1 mechanical advantage to transfer them from one anchor point to another, you can use the extra haul rope as a lower out line, you can do a “far end haul” with a 2:1 mechanical advantage if needed, and you don’t need the inverted plastic bottle as a knot protector, because there’s no knot. This is a good place for a triple action carabiner. Yes, the Traxion is expensive.

A swivel goes between the Traxion pulley and the master carabiner. Way less twisting of your rope.

A cam strap connect the long strap and the short straps. This means you never have to lift the full weight of the bags to clip and unclip the carabiner. Clove hitch the cam strap (a 3 footer /1 meter) to the haul point carabiner so you can’t drop the strap. Good place for a triple action (or here, a Magnetron) HMS carabiner. (Side note on the cam strap: After I took this photo, I found out that skotswallgear now makes a very nice 3 foot long cam strap for exactly this purpose, and that's what I'd recommend. Check it out here, scroll to the bottom of his store to see it.

A docking cord attaches the bag to the anchor, not a daisy chain. The docking cord is typically a doubled length of 7 or 8mm cord (about 15 feet / 5 meters) that's attached to the long strap of your bag. With this you tie some sort of releasable hitch onto the anchor, and that holds the weight of your bag. You can release the bag when this hitch is fully loaded, which is a HUGE improvement over hanging your bag from a sling or daisy chain. (Attaching the docking cord to the long strap rather than the hauling carabiner means that when the bag is docked, everything else is slack).

Here's one more tip on where to tie your docking cord (which I unfortunately learned after I shot all these photos). Most haul bags have some sturdy sewn tabs around the opening. If your tie your docking cord to one of these tabs, and around one of the straps, this lets you dock the bag higher up on the anchor, which often makes accessing the bag more convenient.

Tip: Clip a bight knot to back up the Traxion ABOVE the swivel

Just below the Traxion, tie a backup knot (here a butterfly) and clip it with a locker to the carabiner attached to the Traxion. This backs up the Traxion, and gives you a knot you can use to lower out. You can loosely stack all the rest of the unused rope in the top of the bag, or let it hang free.

If the Traxion cam were to open up on some rock nubbin when you're hauling, this backup knot prevents you from losing your haul bag.

Note: It's important to clip this bight knot ABOVE the swivel, and not below it. If you clip the bight anywhere below the swivel, there's a good chance when your bag twists, all of your extra haul rope is going to get twisted around the bag also, no bueno.

Check out the photo below of the correct (left) and incorrect way (right) to do this.

What about two bags?

There are LOADS of different ways to rig two haul bags. The basic concepts (that’ve worked for me) are:

Most folks like the bags side-by-side, but some prefer a smaller bag hanging below the primary bag. Try both and see what works for you.

It’s good to be able to spread the bags laterally if you need to wrestle them around.

You don't want them hanging too far down, so you have to reach uncomfortably low from the anchor. (This is not so important during the day at intermediate anchors, more so at the bivy.)

All connection points need to be unquestionably strong.

You need to able to unclip and separate the bags from one another if needed.

A docking cord connects the bags to the anchor. You can have a separate docking cord on each bag (as we do here) or go with with one single docking cord from the master haul carabiner.

Here’s one way to set it up. From the top down:

Haul rope running through Traxion progress capture pulley, backup knot below traxion, knot clipped with a locker above the swivel

Triple action locking carabiner

Swivel

2 pairs of quick links in swivel. The quick links are unquestionably strong, and give a nice lateral spread to each bag at the belay. (Thanks to Quinn Hatfield for this quicklinks tip.)

HMS locking carabiner attached to long strap on each bag. (Feel free to tape the gates closed if you want to be 110% sure they’ll never open.)

Docking cord attached with quicklink to each bag

On left bag, a 3 foot long camstrap (red)

Here's a close-up:

Here's a fancier way to set it up, from big wall expert Skot’s Wall Gear. Here, Skot is using a pair of gold rappel rings along with a combination swivel and locking carabiner (appears to be the Director Swivel Boss) from DMM. This makes a more compact set up, with zero chance cross loading the rings.

photo: @skotfromthedock, https://www.instagram.com/p/C2nmw-By0-3/

Other hardware for haulbag rigging . . .

There are cool swivels that allows you to open one side. This creates some interesting options; for example you could maybe cut up a PAS tether to get small sewn loops of Dyneema or maybe a pair of quickdraw dogbones, and use these instead of the quick links. I haven’t tried these but looks like they could work.

Here’s a photo: the Petzl Micro swivel and DMM Focus swivel.

Petzl makes a nifty product called the Ring Open. This is a rigging ring that you can open (with a tiny Allen screw, I think), letting you attach a fixed loop. I don't have one of these, but it could be a cool option for setting up your haul bag system.

Like I said at the start, there are many, many different ways to do this. Start with the basic principles, and find a system that works for you.

Director Swivel Boss from DMM. This is the carabiner shown Skot’s photo just above. With this, you can use inexpensive rappel rings instead of the more expensive Petzl Ring Open.

The far end haul

Having a Traxion on the load also lets you set up what’s called a “far end haul”, which at first seems like some sort of sorcery. Here's a detailed article and a couple of how to videos on this technique.

The pre-rigged rappel anchor and belay

Transitioning from climbing to rappelling can take a LONG time. One way to increase your efficiency is for the leader to pre-rig the rappel before they bring up their second. Here's how to do it.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

When you need to rappel the same route you just climbed, the transition at the top can often be a big time suck.

The traditional method of each climber using a tether/PAS to connect to the anchor, each person untying from their respective ends of the rope, threading the anchor, tossing each rope strand, and then each person rigging for a rappel separately, involves a LOT of steps and (usually) waiting. It can also be awkward at tight stances and can take a LONG time, especially with less experienced folks.

Here’s one way to increase your transition efficiency: If you know you need to rappel the route you just came up, the leader can take a minute or so on top to pre-rig the rappel BEFORE the second starts to climb. With this method, you can start rappelling in just a minute or so after the second arrives at the anchor. This can especially be a timesaver if your second is less experienced.

This method is closely related to the backside clove hitch rappel transition; read more about that method here.

I first saw this technique demonstrated by IFMGA Certified Guide Rob Coppolillo. Rob calls it the “BARF” anchor, because the rope from the “BA”ckside of the leader’s tie-in is rigged for “R”appel by “F”eeding it through the anchor, hence the great name. It hasn't caught on yet, what do you think?

As mentioned above, this is absolutely something to practice on the ground in a controlled environment, ideally under the eye of a qualified instructor, before you ever try it in the real world. This process might sound a little complicated, but after you think it through and practice it a few times you’ll see that it’s pretty straightforward.

This might appear to give an uncomfortable belay, but that's not necessarily the case. If your tether of your extended rappel is reasonably long, it works out to be quite comfortable, and you're not twisting your back too much.

Hopefully this is blindingly obvious, but this only works if you are descending a pitch that's less than half the length of your rope. (Which, if you’re considering rappelling the route, should definitely be the case!)

If your second has belayed you to the anchor, and the middle mark of the rope has not yet gone through their belay device, this method will work.

Conversely, if you pull up the rope, and you reach the middle mark before the rope goes tight on your second, this method will work.

If either of these two things are not happening, your rope is too short and you should probably not be rappelling this route!

Advantages:

Fast and efficient transition from climbing to rappeling

Cluster free anchor. No need for multiple leashes clustering up the anchor. You have plenty of room to stretch out and move around a bit, depending on stance. Your position isn’t limited by a short tether or PAS.

Always using the dynamic rope to connect everyone to the anchor. Ropes are stretchy. Stretchy is good.

Only need to toss one rope strand, because the second can stay tied in and takes one strand down with them.

No need to tie a knot in the end of the rope, if the second raps first. This is because the second stays tied in, and the partner is blocking the other strand from moving with their pre-rigged rappel.

What you need:

An easy-to-see middle mark on your rope. Add one if your rope doesn’t have it or if it’s worn away. The Beal rope marking pen is great for this. In the field, you can use tape as a temporary middle mark.

A rappel extension and anchor tether with a locking carabiner. Consider pre-tying this with a 120 cm sling to your harness before you leave the ground; you know you're going to need it, so why not have it ready to go in advance?

Ideally a second rappel device, plain tube style device works fine. Or, you could bring up your second on a munter hitch, see example below..

Here’s the sequence:

This might sound complicated when you first read through it, but once you get your head around the whole process, the steps go very quickly, as you can see from the video link below.

(There are several variations to doing this. I'm going to mostly describe the sequence that Karsten shows in his video.)