Alpine Tips

Mechanical advantage calculator from alpinerecreation.com

Here's a link to a very cool online mechanical advantage calculator! Choose your rigging method, choose your components, choose your load, click a button, and you instantly see all of the different forces in the different legs of your rigging system. Courtesy of the New Zealand-based guiding company, alpinerecreation.com.

I recently came across this clever online tool from alpinerecreation.com, a New Zealand based guiding company.

It’s a mechanical advantage calculator, very cool!

This is an excellent way to instantly see some of the forces involved with different rigging methods, and how using a carabiner rather than a pulley can change the efficiency of your system.

(Works fine on a mobile phone but it's easier to see the big picture on a wider computer screen.)

Choose your hauling system (2:1. 3:1, 5:1, 6:1, etc.)

Choose your components (Micro Traxion, rescue pulley, large carabiner, small carabiner, etc.)

Choose your load (default is 100 kg)

Choose your units (percentage of load, kg, or kN)

Press “Calculate” and it gives you values and forces all the way through the system!

Here’s a screen grab showing values for a 3:1 Z drag, using a Micro Traxion as the progress capture and a good quality pulley on the “tractor”.

image: https://www.alpinerecreation.com/mechanicaladvantagecalculator.html

DIY - Protect shoe threads with super glue

Are you battering your light hikers with rough terrain? Super glue on the shoe threads will help.

You can increase the amount of mileage you can get out of trail runners and lightweight boots by coating all the threads on the seams with super glue.

It protects the threads and stops any fraying from spreading if it does start.

image - blog.buyskateshoes.com

Gaia GPS tip- long touch to measure distance between map points

In Gaia GPS, the “create route” tool is a sort of hack to quickly see the distance between two or more points on your map.

Gaia GPS is the favorite GPS navigation app here at AlpineSavvy. Here’s a Gaia tip to quickly measure distance between two or more points on a map.

In Gaia GPS, if you long touch the map screen, that starts the “create route” function.

This is a handy way to get a quick direct line distance between two or more points.

Zoom in to your area of interest. Long touch your first point. A blue dot should appear on your screen, and a small box showing the distance and bearing from your current position.

Look in the lower left corner of your screen. You should see a bird icon which indicates “as the bird flies”, or straight-line distance.

If you want the actual driving or hiking mileage between points, tap the “mode” icon and change it to hiking or driving.

Do another long touch on point B.

A red line should draw between the two points, and the line should be labeled with the distance in miles.

Continue long touching any additional points as needed. The length of each leg will show on each red line, and the cumulative distance is on a graph at the bottom of the screen.

Make a note of the distance, then tap cancel at the top to delete that route.

Examples: Straight line distance between 2 cities:

Rough mileage around Green Lake Park in Seattle. You can see the links of each short leg on the red lines, and the total length at the bottom.

Two good reasons to mark the middle of your rope

There's two good reasons to mark the middle of your rope. One is hopefully pretty obvious, the other one not so much, but perhaps more important.

There's two smart reasons to mark the middle of your rope. The first one might be rather obvious, the second one perhaps less so, but it may be more important. Let's have a look at both.

1 - Setting up a rappel

Knowing with certainty that the middle of your rope is at the rap anchor is a Good Thing. Of course, if you cut off the end of your rope for any reason, this middle mark becomes less accurate. But that is pretty darn rare, so a permanent mark on your rope should last you for a long time.

Yes, you can do the trick of measuring hand spans to find the middle of your rope, which actually is pretty darn accurate, but having a middle mark makes it idiot-proof.

2 - Belay Safety

This is one people may not think about right away, but it’s arguably more important. For decades, pretty much everyone climbed with a 50 meter rope, and you would never find a single pitch sport climbing anchor more than 25 meters off the ground. But many newer routes are longer, requiring a 60, 70 or even 80 meter rope. Because these long routes are generally newer, they may not appear in a guidebook, and there's often not a reliable way to tell at the base of the route precisely how long it is.

If you’re belaying the leader, and you notice the middle mark of the rope pass through your belay device before the leader has reached the anchor, that should ring a LOUD alarm bell in your head! You're not going to have enough rope to lower them off and reach the ground, and you need to figure out a crafty solution to a potentially serious problem.

A quick review of the report/book “Accidents in North American Climbing”, published annually by the American Alpine club, can confirm that this is a recurring problem. One likely cause is the increase in the number of routes that require a 70 meter rope, as mentioned previously.

Another contributing factor is probably more gym climbers venturing outside. In a gym, routes are almost always less than 30 meters tall, and therefore the 60 meter rope that many gym climbers have for leading is guaranteed to be long enough.

While many people climbing single pitch routes from the ground don’t bother tying into the end of the rope or even having a stopper knot, doing either of these simple fixes eliminates the problem of potentially dropping your leader when you’re lowering them off.

(Even if you have a 70 meter rope for a route designed for it, if those anchors are close to 35 meters off the ground, and the belayer decide to back up a little bit, that could still cause you to end up short when you’re lowering. So, just having a 70 meter rope doesn’t necessarily eliminate the problem.)

So, how best to mark the middle of your rope?

There's been a L O N G debate on the interwebs about the safety of using things like Sharpie pens and laundry markers to mark the middle. We’re not going to rehash those here.

An excellent choice is to go with a designated rope marker made by the French company Beal, one of the largest rope manufacturers in the world. It’s inexpensive and has a specially formulated ink in a handy dispenser that's designed for climbing ropes. Get one, use it, and share the extra ink with your friends.

Beal rope marker

If you want to make a quick temporary mark, find the middle of your rope and then put some tape on it if you have some. This is a short term solution, because it doesn't pass through a belay device very well and can fall off.

Summary:

If you’re leading a lot of sport routes outside, you probably want a 70 meter rope, which is pretty much the new standard.

Put a middle mark on your rope if it doesn’t have one. Use it to set up rappels and also for belay safety.

Use the generally accepted best practice of a closed rope system. For toproping, this means the belayer is either tied into the end of the rope, has a solid stopper knot tied into the end, or has the end tied to something reasonably heavy like a backpack. to avoid any chance of dropping the leader when lowering.

Think you’d never make a mistake like this? Well, if it can happen to Alex Honnold, it can damn sure happen to you.

In 2016, Alex was dropped by his belayer because they were using a 60 meter rope on a 70 meter route, there was no knot in the end of the rope, and his belayer was not tied to the end of the rope. While she was lowering Alex, the end of the rope zinged through her Grigri and Alex fell onto some “gnarly rocks”.

Would a middle mark have prevented this accident? Hard to say. But it would not have hurt anything.

Read the complete accident account here, from “Accidents in North American Climbing”, an annual publication of the American Alpine Club.

Below is a copy paste.

I had run up the route Godzilla (5.9) to put up a top-rope for my girlfriend and her family. At the last second her parents asked us to hang their rope instead of ours. I didn't think about it, but their rope was a 60m and mine was a 70m. I was climbing in approach shoes and everyone was chatting at the base—super casual, very relaxed. As I was lowering, we ran out of rope a few meters above the ground and my belayer accidentally let the end of the rope run through her brake hand and belay device.

I dropped a few meters onto pretty gnarly rocks, landing on my butt and side and injuring my back a bit (compression fracture of two vertebrae).

Analysis

Lots of things should have been done better—we should have thought about how long the rope was, we should have been paying more attention, we should have had a knot in the end of the rope. I wasn't wearing a helmet and was lucky to not injure my head—had I landed on my head, it probably would have been disastrous. My belayer had been climbing less than a year. Basically, things were all just a bit too lax. (Source: Alex Honnold.)

A Better Way to use your compass lanyard

Most people think the string/lanyard on your compass is for hanging around your neck. That’s actually not the best place.

Most good quality compasses, such as our favorite, the Suunto M3, come with a lanyard cord. Many people assume this is for hanging the compass around your neck.

You could do this, but unless you’re about 3 feet tall, you’ll find that in order to properly use the compass to take a bearing by holding it at your waist, the cord isn’t long enough. So, if you hang the compass around your neck, every time you want to use it, you have to take it off, which is kind of a bother if you’re using your compass a lot.

Here’s a better approach. If you are using your compass a bunch, girth hitch the lanyard cord through a belt loop, near the front pocket of your pants or shorts, then just put the compass in your pocket.

There’s two main advantages to doing this. One you can easily hold the compass at waist level to take a bearing, and two, you can never lose your compass because it’s permanently tied onto your pants.

Now, let’s be realistic, 99% of the time you are not going to be traveling in the backcountry with your compass glued to your hand like this. But for those times when you do have to use it, this is a great way to carry it.

Survival shelter for an unexpected night out

Looking for a lightweight, inexpensive and versatile emergency backcountry shelter? Using these two common items in combination is a great choice.

In the book “Analysis of Lost Person Behavior” author William Syrotuck analyzed over 200 rescue cases. He found that 11% ended in fatalities, and three quarters of those people who died generally did so from hypothermia, within the first 48 hours of becoming lost.

So, to look at these statistics in a more positive way:

If you’re lost, you have an approximately 90% chance of surviving.

If you can stay alive for 2 days and minimize the chances of getting hypothermia, your survival odds increase to around 97%.

Therefore, carrying some kind of emergency shelter is an excellent idea.

But what, exactly does that mean? A one person tent, a tarp, a bivy sack, maybe even a bothy bag, which is kind of a British invented combination of all three? Or something more minimal?

If you have a reasonable chance of spending a night out, you probably want something fairly substantial, like a bivy sack and tarp. But, if you're after something to keep in your hiking day pack for emergency use only, something lighter which takes up less space is probably a better choice.

For emergency use, go with simple: a heavy duty garbage bag. Cost: about $1, weight, about 5 ounces.

As a survival shelter, cut a small slit in the side end for your head, see the video below. If you're about 5’ 9” or smaller, you can probably crouch over and get most of your whole body inside the bag. If you're much taller than that, you might want to bring two bags, one for your feet and one for your torso and head.

Also, the bag serves as a rain cover for your pack, and is easily converted into a poncho if you cut a hole for your neck and arms.

Be sure and get the heavy duty “contractor clean-up bags”, that are huge (typically 43 gallons) and 3 mil thick. (Side note: a “mil” means one 1000th of an inch, and is a standard in the United States for measuring the thickness of plastic. It’s not a millimeter or a milliliter.)

At the big box hardware stores, you usually need to buy a humongo box of 50 of these, so if you know anyone who’s a builder you could ask them for a couple of extras. Or, they’re available on Amazon as a more reasonably sized box of 20.

After some hunting around, I was able to find some that are orange, better for increased visibility, unfortunately available in a pack of 50. So I've been sharing them with various climbing friends and students over the years. Try a Google for “orange 3 mil 42 gallon contractor trash bags". I found mine from plasticplace.com.

Many backpacks have a water bladder pocket, or maybe a pocket to hold a foam pad as part of the suspension. You can slip the bag in this pocket; you're not notice the weight and it’ll always be in your backpack.

These are the bags I got from Amazon:

Here is a nice short video from the excellent MedWild YouTube channel on making a quick emergency shelter with a garbage bag. Note that he cuts just a small hole in the SIDE of the bag, which lets you breathe and see, but keeps your head protected.

Many people want to cut a hole for your head in the top of the bag, which keeps your head exposed. The hole in the side is much better. Here's a screen grab from the video showing this simple technique.

image: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=baTeliYY9lc&feature=youtu.be

And here's the whole video:

What about mylar “space” blankets or mylar bivy sacks?

Lots of people carry these for emergency use. But they have a few issues:

Yes, they can reflect some of your body heat back, but if you're getting hypothermic, there's not much heat being generated in the first place. If you have proper clothing on, that should be doing its job of keeping heat close to your body.

If you have the mylar against your bare skin, the blanket will conduct the heat away from you into the cold air. The same thing happens if you put it on bare ground, heat conductivity from your butt into the earth.

The very inexpensive ones are extremely fragile and start ripping if you sneeze on them, so don't even bother buying those.

Most emergency bivy sacks are pretty much non-breathable, so you can expect to get a fair amount of condensation and wetness inside your bag. The advantage to the garbage bag is that you can get a bit of airflow from your feet up through your head, which minimizes condensation.

Given the choice between a garbage bag and a mylar space blanket, take the garbage bag.

The mylar blankets and bags may not be very good when used by themselves, but they do have some other wilderness survival applications. If you do choose to take one, spend just a few extra bucks and get one of good quality that's much sturdier. SOL makes some nice ones, called Heat Sheets. They cost just about $10 for a 2 pack.

CalTopo tip - Try the "MapBuilder Topo" layer

Caltopo has one map base layer that’s a superb choice for most any backcountry adventure - MapBuilder Topo. See a side-by-side comparison of the old-school USGS map.

If you're new to using CalTopo mapping software, watch this tutorial to get started.

CalTopo, in my opinion the best online and free mapping software, continually rolls out great new features. There’s a (relatively) new map layer, called "MapBuilder Topo” that is a terrific option for printing outdoor recreation maps. It's a big improvement over the standard USGS 7.5 minute map layer.

What’s cool about it?

Shaded relief (shows terrain features like ridges and gullies more clearly)

Easy to see and well-labeled contour intervals

Roads and trails easily visible and labeled

Some distracting non-essential map information (such as unnecessary text, public lands survey section lines and wilderness boundaries) removed or made less prominent

County lines added in yellow (it’s helpful to know what county you‘re in if a rescue is needed)

Shows approximate vegetation and terrain boundaries, such as forest, rock, and snow/glacier, even crevasses

Have a look yourself!

Go to caltopo.com

Mouseover the “Base Layer” icon in the top right corner

Select "MapBuilder Topo” from the drop down menu (should be the first choice at the top)

Zoom in to your area of interest. Swap back and forth between this map layer and USGS to see the differences. (Note that the map tiles may take longer to generate on your computer and also to print when using this layer.)

Here’s an example of Mt. Hood south side in the standard, old-school US Geological Survey 7.5 minute topo map.

Note that there’s no relief shading, trails are hard to spot, there’s unnecessary “Mount Hood” text in a large font, the chairlift isn’t shown. Not bad, but definitely room for improvement.

Now, here’s the same map area in the MapBuilder Topo layer. Improvements:

the relief shading makes the gullies and ridges much more obvious

county line (yellow) is labeled

ski chairlift is shown (very handy for finding your way back down in low visibility)

trails are clearly delineated and labeled

every index contour has an elevation label

green wilderness area boundary is current and correct

Which map would you rather use? The USGS 7 1/2 minute maps for many decades were the only game in town, and unfortunately that’s what some old-school navigation classes and textbooks still advise you to use. But, for most people and most activities, these are no longer the best choice.

Get with the modern times, learn to use mapping tools like CalTopo, and you can have a superior map for free!

And, if you think CalTopo is great, I strongly encourage you to support CalTopo with a $20 annual subscription. There is just one guy running this entire software platform, and your modest annual subscription can help ensure that this great service continues on into the future.

Having a subscription also gives you some nice perks, like being able to print on larger size paper, and being able to save and share your maps to the cloud. When you consider that a single commercial map of just one area can cost between $10 and $15 at the outdoor store, a $20 annual subscription to this mapping software is a pretty screaming deal.

Need to learn the basics of CalTopo? My tutorial video will get you started.

Add custom map layers to GaiaGPS

Gaia GPS is a great navigation app for your smartphone, with loads of map layers to choose from. Even so, you may want to access ones they don't have, such as Google Earth satellite imagery or Open Topo. Adding a custom map layer is easy once you know how.

Gaia GPS is regarded as one of the best backcountry GPS apps for your smartphone. They offer a wide variety of base maps to choose from, but one of my personal favorites, called Open Topo, happens to not be one of them.

What makes Open Topo a terrific choice for outdoor adventures? It has nice shaded relief (which makes features like ridges and gullies much easier to see), updated trails and roads, and land cover, such as forest, rock, or snow. (One potential curveball for Americanos - elevations and contours are in meters.)

Go have a look yourself. Go to opentopomap.org and zoom into your favorite part of the world.

Here’s a screengrab of Mount Rainier in Open Topo. Pretty cool, eh? Like I said, elevations are in meters.

The one small downside is that it is not part of the Gaia GPS app.

The good news is, with a little computer sorcery, you can add this as a custom map layer to your Gaia GPS phone app. Here's how to do it.

These steps might sound a little complicated, but it's pretty straightforward. Keep this webpage open in a browser tab so you have a reference.

Here's a nice video that shows how to do it, using Google Earth.

Here are the step-by-step instructions, for a different map source as mentioned above, Open Topo.

1. On a desktop computer (not your phone), go to GaiaGPS.com. Log in to your account, or create an account if you don’t have one.

2. Click your user name (top right of screen), and from the drop down box select "Map Sources".

3. Click "Import an External Map Source".

4. In the “Name the Map” box, give it a name. I suggest a simple, descriptive, name, like “Open Topo custom“.

5. Scroll a bit lower, locate "Paste your modified link here"

6. Copy and paste this link in that box:

https://c.tile.opentopomap.org/{z}/{x}/{y}.png

7. Scroll to the bottom, click "Add this Map Source"

Go to your phone.

8. Make sure you are signed in to your Gaia account on your phone. [Settings icon > Account > Login) and that “Sync/Backup” is toggled on.

9. Restart the app.

10. Tap the Map Sources icon, top right of your screen. Tap Edit, then scroll to the bottom and tap “Custom Imports”.

11. You should see “Open Topo Custom” here, or whatever you decided to name it. Select this map layer to add it to your viewable layers. You should now be able to use Open Topo on your phone.

Below is a phone screengrab of Mt. Rainier in Gaia GPS Open Topo map layer, with climbing GPX tracks in blue and green.

See the Exact Right Spot with lat/long coordinates on Google

Google maps and driving directions works great in the city, where places have street addresses. But what do you do in the backcountry? Answer: use latitude longitude coordinates in decimal degrees, to pinpoint any spot in the world and (usually) get driving directions to it.

Most of us have suffered through trying to follow well-meaning but wildly confusing directions to get to a remote trailhead or campsite on obscure fire / logging roads.

The directions usually look something like: “Turn off the main road, then go to .7 miles on Forest Road 1234. At the 3-way fork, take the middle fork on road 1234-10, then go 3.2 miles on that, and then . . . ” You get the idea. And if any new roads have been added or removed since the guidebook got printed, or some local yahoos have been shooting up the road signs so you can’t read them, then things REALLY get confusing!

Here’s a superior system for giving a precise location, and ideally directions, to most anywhere that doesn’t have an actual street address. Which is most of the fun places we want to go play, right?

If you type latitude longitude coordinates (preferably in decimal degree format) into a Google search or a smartphone mapping app, it places a marker directly on the spot. You can then get driving directions to it.

Try it! Here’s the lat long coordinates in decimal degree format for the Mt. Thielsen trailhead in southern Oregon:

43.1459, -122.1277

(If there are any guide book authors reading this, can you please please please start using latitude longitude decimal degree corners to describe Important Places in your book?)

Note:

- Use a comma between the latitude and the longitude.

- Be sure to include the “minus” sign before the longitude. This indicating west longitude rather than east. If your intended map of the Pacific NW instead draws in China, then you probably skipped the minus sign. =^)

Note the number of decimal places. In this example, we are using four. If you use less than four decimal places, Google doesn’t recognize it as a coordinate and thinks it’s some kind of a math problem.

Four decimal places gives you positional accuracy down to about 3 meters. We’re not measuring property boundaries here, so for things like finding your tent in the woods or locating a trailhead, four decimal places is fine. If you use a GPS app on your phone, you may see a coordinate of six or even seven decimal places. This is theoretically accurate down to sub 1 meter, but that’s a little deceiving because the GPS chip on your phone is not that good. When I get a six digit coordinate from my phone or mapping app, I usually just remove the last two digits until I get down to four decimal places. That is simpler and easier to transmit and write down.

You can get decimal degree coordinates in several ways.

Probably the easiest is to go to Google maps and zoom in on your area of interest. Right-click, and choose “What’s here?” This opens a pop up box. The latitude longitude coordinates in decimal degrees, of the exact point you clicked, appear at the bottom of the box. Copy and paste the coordinates into a new Google search to test. If it draws your spot correctly, your coordinates are correct.

Go to caltopo.com, the best online mapping software. Using the different map layers from the upper right corner, choose one that lets you zoom in to your area of interest. The coordinates of the cursor are shown in the upper right corner. Change the coordinate type to “Degrees” from the “Config” menu at the top of the page. Also, you can right click and choose “New > Marker”, and you should get a pop-up box with the location of the coordinates, which you can then copy and paste.

Note:

- UTM coordinates, the preferred coordinate system for backcountry navigation with map and compass, are NOT recognized by a Google search.

- Latitude longitude coordinates in the traditional degrees minutes and seconds and the more specialized format called degree minutes ARE recognized with a Google search, but these are harder to obtain and it’s easy to screw them up when you enter the coordinates. (The “degree minutes” system is typically used by electronic navigation systems in ships and airplanes, and usually not much by civilians.) So, it’s usually best to stick with decimal degrees as shown above.

Other examples of coordinate systems, all showing the same location, the Mt Thielsen trailhead:

UTM: 10T 570913E 4777387N

Latitude longitude, degrees minutes and seconds: 43°08’46”, -122°07’41”

Latitude longitude, degree minutes: 43°08.76’, -122°07.68’

Suunto compasses - 3 options for wilderness navigation

There are lots of options for compasses. Let’s make it easy - here’s 3 recommended models from Suunto that should cover the needs of every backcountry traveller.

Suunto, a Finnish company with a great track record of quality compasses, makes a variety of models. Here's an overview of three that should suit the needs of most outdoor travelers.

Generally speaking, it's best to choose a compass that has adjustable declination, which I think is the most important feature. Having adjustable declination let you measure bearings to true north, and thus eliminates any confusing backcountry arithmetic such as adding or subtracting declination.

Having said that, I realize that a compass a piece of gear that some people will rarely use and want to save a few bucks on. So. I'm going to suggest three different price points, think of it as good, better, best, so you can choose the one that looks best for you.

(Note that Alpinesavvy does not have any affiliate marketing links, so I make nothing from the Amazon links below. I include them more as a convenience for you.)

Before we get to the recommended compasses, here are two that I do not recommend. Students often show up with these in me navigation classes, but if you're shopping for your first one, please give these a pass.

The Brunton compass on the left is part of the “TruArc” series. They are unfortunately carried by REI, so a lot of people (unfortunately) buy them there. The problem with these is that the declination adjustment is very difficult to do. They have lots of lousy reviews, and I feel you would do better to buy a Suunto, as recommended below.

The rather strange looking green one on the right is a military style “lensatic” compass. It can be very accurate once you know how to use it, and it's probably good for calling in artillery strikes, But it lacks a lot of the features that civilian users need, so for most people it's not recommended.

Good - Suunto A-10 compass

This is a bare-bones compass, but still a quality instrument. It has what is called “fixed declination”, not adjustable declination. But, everything else about it is solid, including the nice curved base plate which ergonomically fits in your hand, always reminding you of the proper way to hold the compass.

Here’s a trick to deal deal with magnetic declination on this compass (or any other similar baseplate compass this does not have adjustable declination). Carefully draw a line with a medium black sharpie pen from the center of the compass to your local declination on the outer dial. Now, when you want to take a bearing or measure a bearing, you line up the red magnetic needle on this pen mark, and not the red orienteering arrow. Of course, this only works if you stay in your local area. If you travel far away where the declination might be different, you may have to erase this pen mark with a little rubbing alcohol or nail polish remover or some other solvent, and draw again. But, it's one option for the frugal climber.

Cost: about $16 (Oct 2018)

Suunto A-10 compass

Better - Suunto M3 compass

The Suunto M3 is my personal favorite, which hits the sweet spot between having all the features you need, and none of the ones you don’t.

Here’s what I like about it:

adjustable declination

long baseplate (for taking accurate measurements from a map and drawing bearings on a map, a long baseplate is helpful)

ergonomic design (the curved part fits your hand, eliminating the common mistake of having the “direction of travel” arrow pointing at you rather than your objective)

low cost (about $15 less expensive than a comparable compass with a sighting mirror)

simple and sturdy (fewer moving parts and hinges mean fewer things that can go wrong in the field)

lightweight (no sighting mirror means less weight)

A few words on sighting mirrors . . .

But what about compasses with a sighting mirror, you may wonder. Don’t offer greater precision when taking a bearing? The short answer: Yes, they do, but for almost all backcountry uses of a compass, you don’t need this level of precision. If you’re doing field mapping or walking a straight line when on a search and rescue team, then the slight increased precision of a mirrored compass might be justified. But for the vast majority of the simpler backcountry uses of a compass, like taking a bearing to an object and then either following it or plotting the bearing on a map, the +/- 2 degrees of accuracy you can get with baseplate compass works just fine.

Also, consider that a mirror compass LACKS most of the good qualities listed above.

Most mirrored compasses:

are not ergonomically designed

are expensive

are heavy

have more moving parts that can break

I have used my Suunto M3 compass to take a bearing from a map, follow that bearing cross country for more than a mile, and hit my precise objective . . . at night. With a little practice, you can too. Don’t throw away your mirror compass if you already have one and like it, but if you are looking for a compass to buy, the Suunto M3 or similar model is a better choice for most users.

Cost: about $30 (Oct 2018)

Suunto M3 compass

Best - Suunto MC-2

I know that some people will want a compass with a sighting mirror and possibly a clinometer. Both of these features are found on the Suunto MC-2, which is the next model up from the M3 in terms of the whistles and bells. This costs about $40-$45. Again, I feel this model is not necessary for the majority of users, but if you want these extra features, this compass is a great choice.

Cost: about $45 (Oct 2018)

Suunto MC-2 compass

DIY - Duct tape on the Jetboil pot

Ever drink a hot beverage out of your Jetboil pot? Yep. Ever burn your lips when you're trying to do it? Probably. Pro tip: Add a strip of duct tape onto the pot lid so you can leave that mug at home.

Do you ever use your Jetboil pot as a coffee cup or soup bowl?

Sure you do.

Tip - Put a small bit of duct tape on the rim of the pot so you don’t burn your lips.

Racking your cordage - Do the Twist

A basic climbing skill is knowing how to rack your cordage In a tidy and fast manner. One great method: Do the Twist. Learn how in this short video.

A basic climbing skill is learning to rack your cordage - slings, runners, cordelettes, prusiks - quickly, in a tidy loop, and making sure they never hang below your knees, where they can trip you up.

I've seen lots of people take several minutes to rack their cordelette with some cutesy macramé project. Yes, it may look nice on your harness, but I prefer simple and speedy, especially for gear that you're using every pitch. Here's one good way to rack it:

Do the Twist!

If you take any sort of loop (sewn or tied), twist it a few times, and then hold the ends together, the material will rather magically do this sort of double-helix twist around itself, resulting in a tidy, compact bundle.

It may look like a complete mess, but to deploy, simply unclip it, give it a shake or two, and it should return itself to full length, ready to use.

This also works with 60 cm slings and even a long cordelette. You need to double up these longer slings to get them down to about two feet long before you start.

As we'd like to say around here, this one is a better show than a tell. Here’s a quick video demo on how to do this.

Cordelettes - what length and diameter?

Cordelettes - If you want to use one, the first choice is diameter and length. There are some standards, but which one you pick might depend on what kind of climbing you’re mostly doing. (If you climb a lot on snow and rock, you might want to get one for each.)

If you choose to carry a cordelette, the first questions are: what diameter, and how long?

For snow climbing or glacier travel, consider 4 meters of 6 mm cord.

For rock climbing, consider 5 to 7 meters of 7 mm cord.

6 mm cord is dramatically less strong than 7 mm. But, on snow or lower angle alpine ice, you can build anchors usually pretty much wherever you want to, and usually the impact of a fall is going to be fairly low. Because of this, you can probably use a shorter, smaller diameter cord.

On rock, it’s the opposite. You’re going to have potentially higher impacts on the anchor, and your placements have to align with what the rock offers you and the gear you have left, which means they may be farther apart. Both of these point to using a longer, larger diameter cord.

Cord strength (a kilonewton is a metric unit of force, equal to about 220 pounds)

5mm - 5.5 kN

6mm - 7.5 Kn

7mm - 13 kN

Look at that jump in strength going from 6mm to 7mm! For me, that’s a pretty compelling reason to use 7 mm cord for rock climbing. But hey, don't take my word for it, keep on reading for more expert opinion.

Try tying it “bunny ears” style, with a small figure 8 or overhand loop in each end, rather than the standard configuration of one big loop. Because the bunny ears style gives you a wider reach, you may find you can get away with a shorter length cordelette. But try climbing on the slightly longer cord for a while and see what you like. (You can always cut off a meter if you think it’s too long, but you definitely can’t add one back on.)

Expert climber Steph Davis address the cord diameter issue on her blog, by consult with an expert from Mammut. He says to always use 7 mm cord. (Bold text below is mine,)

From: https://stephdavis.co/blog/cordelettes-for-climbing/

“Although some climbers may use cord thinner than 7mm for constructing belay anchors, it is important to note just how much stronger the slings and 7mm cord are in comparison, especially when you consider that these are often weakened by knotting them and by concentrated wear at the knots.

We definitely do not advise people to use 5 and 6mm cord for anchor construction, and if climbers choose to do so they should be acutely aware that they are putting themselves at extra risk by doing so and take any necessary precautions (frequent wear-checks, being extra conservative in deciding what is worn and discarding it, always placing protection specifically to protect the belay from high impact, using a dynamic belay device and techniques, terrain and belay location choices, etc).

A calculated risk may be acceptable to some people if it is truly calculated, but done out of ignorance or by guesswork it is asking for trouble. Because most people aren’t willing or able to objectively test these out for themselves to see what their true level of safety (or lack thereof) is, if a nylon cord is used I’d strongly recommend using 7mm for anchor construction, and if the weight and bulk is a significant problem using a Contact sling with a 22kn breaking strength, remembering to tie into the anchor with the rope.”

Dave Furman, Hardgoods Category Manager, Mammut Sports Group, USA and Canada

Google Earth screen grabs - The best route beta tool?

Google Earth is great for wasting time at work, but it's good for a lot more than eye candy. Learn a few tricks about how to scope your route at home, complete with a route line and annotation added.

Most climbers know that Google Earth (aka GE) is a great tool for scoping out your route at home and getting a feel for the terrain. But, with a few other simple steps, you can take GE to a whole new level of usefulness.

Before we proceed, a couple of tips.

Have Google Earth Pro installed on your desktop computer. It's now free (it was $$399 before 2015!), and has some additional functionality over the web base software. And, it's a lot easier to navigate than the GE phone app. A desktop computer is easier to use than a tablet.

At least for my clumsy fingers, GE is MUCH easier to use if you have an external mouse with a scrolling wheel. Highly recommended.

Mt. Stuart WA Cascades, West Ridge route in Google Earth, with imported KML track and waypoints. That's what I'm talking about!

As we like to say at Alpinesavvy, having a map or photo is great, but having a map or photo with your route drawn on it is much better. And, when you can see your route in 3-D with high resolution satellite imagery, it gets even MORE better!

Here’s the general workflow, with a longer explanation below.

Find a GPX track file of your route.

Open it in Caltopo, and export it as a KML file.

Open the KML file in GE

Make a few screen grabs

Annotate your route in photo editing software (optional)

Print your images if you want, and/or save the edited image(s) to your phone or Google Drive for offline viewing and sharing with your team

Step 1 - Find a GPX track file of your route

You can get track files for more than 70 of the most popular routes in the Pacific Northwest right here at Alpine savvy at this link. If You want a peak that's not on this list, a good place to go is peak bagger.com. We cover how to find GPS tracks at Peakbagger at this article.

Note that if your GPX file has both lines and waypoints, the resulting KML export will have both of these features also. This is great for showing both the climbing route and point features such as water sources, good campsites, important trail junctions, etc. Pro tip - If you name your waypoints in Caltopo, such as (“climber trail junction”, “rappel” or “campsite”), these waypoint names will appear in Google Earth in your KML file. Very helpful!

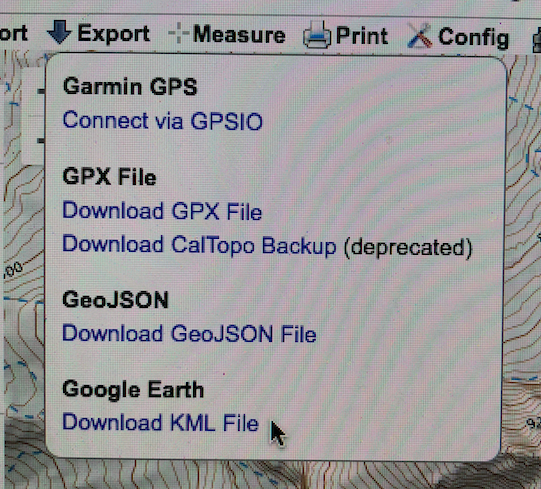

Step 2 - Open it in Caltopo, and export it as a KML file

Caltopo is pretty intuitive. Go to Caltopo.com, import the GPX track, then choose Export > Download KML File from the drop-down menu on the top. (Alternatively, you can download a single zipped folder of KML files for most of the popular mountain peaks in the Pacific NW right from this website.)

Below is a screen grab of what this looks like in Caltopo.

Step 3 - Open the KML file in GE

A KML file (or Keyhole Markup Language, for you computer nerds), is a file of geographic data that plays well with GE.

Once you have the KML file on your hard drive, double click it to should launch GE and draw your KML file. (Or, you can launch GE, and just drag and drop the file onto the GE screen.) Zoom in close, and waste another 10 minutes of your life in GE land flying around your route. (Ever notice how it’s always a bright sunny bluebird day in GE land? Apparently it never rains there. =^)

Step 4 - Make a few screen grabs

So, you’ve zoomed and rotated GE around until you find a few good spots that show the key points of your climbing route.

Now it’s time to do a few screen grabs. GE makes this easy.

Zoom and pan to just the spot you want to capture.

Go to File > Save > Save Image.

Click the “Save Image” button at the top of your and it will save a JPEG image file to your hard drive. Don’t be shy, fly around and take several different shots. You don’t have to keep them all.

Tip: Take screenshots from a variety of different heights, from zoomed out several thousand feet in the air to zoomed WAY in, just hovering above your route. When you zoom way in close to the ground, you get a more realistic view of what you are really going to see, a big help in making route finding decisions. It can be a little tricky to find just the right spot, that's where the external mouse with the scroll wheel can come in handy.

Below - GE screen grab from the start of the Fisher Chimneys section, Mt Shuksan WA, a notorious place to have route finding difficulties. This shot is taken zoomed in quite low to the ground, and looking up the route This more realistic “human-eye” view like this can be a great help in the field.

And notice with the high resolution satellite imagery, you can actually see the climber trail, very helpful also.

Here's a more oblique, birds-eye view of another route on Mt. Hood.

Step 5 - Annotate your route in photo editing software (optional)

Most of the time having a simple redline in the photo from the KML file is going to be enough, but if you want to get fancy you can add additional route info / text onto the photo.

Open your JPEG in some simple image editing software. You don’t have to be a Photoshop wizard to do this. I happen to like some free software called “PhotoscapeX”, but there are many options.

Add in arrows showing hazards, maybe mark where the rappels are, add elevation to key decision points, show the descent route if it’s different than the way you went up . . . You get the idea.

Step 6 - Print your images if you want, and/or save the edited image(s) to your phone or Google Drive for offline viewing and sharing with your team

If you like hard copies, print out your screen grabs and bring them with you on your climb for reference. A color laser printer is more weatherproof than an inkjet. Be sure and put them in something to protect them from the weather, a 1 gallon Ziploc bag is perfect.

Email the photos to the rest of the people on your climbing team, so they have the benefit of your efforts.

Finally, get those photos back on your phone so you can reference them on the route if you need to. Email them to yourself, save to photo roll, or whatever crafty thing you like to do on your phone to save photos. Now you have a free and weightless back up to your printed photos.

(Or, as we cover in this Tip, a convenient way to keep a lot of image files like this handy on a climb or hike is to store them in Google Drive in a designated folder, and then select each of them to be available offline. This lets you view the photos when you don't have cell coverage.)

A slight caution: GE tends to flatten out pointy peaks

If the summit area is especially steep/pointed, at present (2018) GE may display it as significantly flatter than it is in reality. Do not be suckered into thinking that the most technical part of the climb is an easy walk up, always check route descriptions and look at a contour map to see for yourself.

Here's an example in the Oregon cascades, Mt, Thielsen, probably the “pointiest” summit in the whole state.

This is what it looks like in a Google Earth screen grab (Amazing detail, you can see the climber trail.)

This is what it looks like in real life - Quite a bit different! There is one pitch of 5.easy climbing at the top but it has about 2,000 feet of exposure, so pay attention.

Now, this procedure may sound a little complicated and time-consuming when you’re doing it for the first time or two. But trust me, when you get this down it takes literally a few minutes.

Google Earth is a great way to visualize the terrain before you leave town, and also have a great navigation tool en route in addition to your map, compass, and navigation brain.

Gearspeak: What’s an “HMS” carabiner, and why do you want one?

Many books refer to an “HMS” carabiner. What ‘da heck is that, you might be saying? If you don't speak German, that’s an excellent question. Here's why using one as your main belay carabiner is a good choice.

Note: thanks to Richard Goldstone for some German proofreading in this post.

A techie climbing term you may come across is an “HMS” carabiner. What ‘da heck does this mean? (Hint, it’s not “Her Majesty’s Ship.”

If you don’t speak German, it’s a reasonable question.

It’s actually an acronym for “Halbmastwurf sicherung”, which loosely translates as “Munter hitch belay carabiner.” Let’s break it down.

“Halb” = half

“mastwurf” = mast hitch, aka clove hitch

“sicherung” = to protect or secure; in climbing it refers to the belay

So an “HMS” carabiner is, roughly, the “half clove hitch belay” carabiner, a large, locking pear-shaped carabiner, suitable for belaying with a Munter hitch.

(Side note - belaying the second with a Munter hitch directly off the anchor might seem a little old-school, but it’s a very useful technique that every climber should know. Read more about how to do it here.)

In American climber slang, this sometimes gets shortened to a “pearabiner”, which is certainly more descriptive.

Look, they’re almost cousins!

One of the advantages of using a pear-shaped carabiner like this is that the bottom edge is wide and relatively flat. This offers a few benefits.

One, as the name implies, you can easily belay off of this with a Munter hitch, because the wide gap in the bottom allows the knot to flip back and forth as you take in or let out rope.

Two, the wide and flat bottom allows you to clip other carabiners onto it, and add them and remove them fairly easily, even if one carabiner is loaded. If you were to use an asymmetric or “D” shaped carabiner on your master point, the loaded carabiner will often pinch down on the other ones, making removal much more difficult.

This can be especially helpful on big wall climbing, when the first step to build an anchor is usually clipping a large pearabiner into each of the bolts, and locking the gates. Everything else you add to the anchor typically gets clipped into those primary carabiners.

And, there are some old school safety police out there reading this, who are probably having a FREAKOUT right now that I’m advocating clipping one carabiner onto another. Don't worry, they’re lockers, and it's fine to do it at an anchor. But if you don't like it, you don't have to.

Close up of master point with an HMS / pearabiner, showing 2 carabiners clipped to it under load.

Expedition hygiene - 6 items for your kit

Heading out for a longer climb or trek, like Kilimanjaro, Peru, or Everest base camp? Having a few extra personal care items along can really go a long way. Here are six goodies you may want in your kit.

If you add these small and lightweight items to your personal kit bag for your next extended trek or expedition climb, you’ll be a most happy camper.

1) Q-tips. You’ll be amazed what you can (carefully) extract from your ears after a week or so at a dusty base camp. (Of course follow the manufacturer’s and your grandmother's recommendation not to put them in your ear canal, yeah right.)

2) Ear plugs. Be sure and bring the ones connected with a string, so you can find them when you lose them in the sleeping bag, which you will. An extra pair is a fine idea too. Available at any hardware store. Vital for a good nights sleep with a snoring tent made or flapping tent.

3) Ayr Nasal saline gel. This is simply saline solution in a slightly watery gel form. The air at altitude holds less moisture, and it can really dry out your nasal passages. If you dab a tiny bit of this gel into each nostril (not as gross as it sounds) you’ll have instant relief from irritating dry nose. Get at any well-stocked pharmacy. (Side note - I had a friend who got up to 26,000 feet on Mount Everest, got an incredible gushing nosebleed from the cold dry air, and actually had to come down because of it. He was convinced that if he had some nasal saline gel, he would've made the summit.)

4) Foot powder. It can help keep your feet drier, smelling much nicer, gives you a nice psychological boost of “Ahhhhh” when you put it on along with a pair of dry socks, and can help avoid blisters. I like Gold Bond brand.

5) Small travel sized bottle alcohol gel sanitizer. Put a dab of this on your feet every night to keep them fresh and kill any bacteria. This can be especially helpful if you are not being so diligent about changing and rotating your socks.

6) Small package unscented baby wipes. A quick wipedown of your more fragrant body parts with a few baby wipes can (almost) make you feel as though you had a real bath. Be sure to get unscented; (you don’t want to smell like a clean baby, do you?) Note, Packets like this may not work if it's seriously cold, like Denali, because they may freeze into a solid block. Instead, looked for individually packaged baby wipes that you can thaw inside your clothing if needed.

Not shown, but can (literally) save your ass: Calmoseptine ointment. This is a zinc oxide and menthol-based thick cream that does an amazing job healing rashes and irritated skin.

Okay, we're getting into the messy details here: if you have some chafing in the sensitive crotch area, it can be debilitating and there aren’t many ways to fix it. This ointment works overnight and you’ll be good to go the next day. Typically it comes in a large tube, but you can buy individual very lightweight packets like this one online. (If you can't find this exact product, I think most any ointment that has zinc oxide based should work in a similar way.)

And here's one intriguing option to the baby wipes, as mentioned by an Alpinesavvy reader: Wysi-Wipes. This clever product is a sort of dehydrated and ultra compressed heavy duty paper towel. It sort of looks like a big antacid pill, and weighs basically nothing. When you add about a tablespoon of water, it magically swells up to be a 9” x 12” useful towel. You can even compost them. On trips where weight is more important and you don't want to carry the wet baby wipes, this could be a great option. (When dry, it looks like a big gauze pad; I’m curious about how these might work in a first aid kit?)

A bag of 100 cost about $12. Here’s a purchase link. (As always at Alpinesavvy, there’s no affiliate marketing, I add just the link so it's more convenient for you to check out this product.)

Use the rope to make an anchor - 2 knots

If you're on multi pitch bolted routes, you may not need any anchor building supplies. The rope and a crafty knot or two are all you need.

Climbing multi pitch routes with bolted, side-by-side anchors? You might want to leave the cordelette and anchor slings at home. All you really need is the rope you’re attached to and two carabiners.

Many experienced climbers (like Peter Croft and Steph Davis) prefer this approach, because it's simple, clean, and requires less gear.

This can also be a good approach if the climbing is tough and run out right off of the anchor, and thus a greater chance for a leader fall to put a large amount of force onto the anchor and belay. Having the entire anchor made out of dynamic rope gives more stretch to the system and will lower the force on all the other components.

Because the leader is directly tied to the anchor, this generally works best of each partner is swinging leads every pitch. If you are not changing leads every pitch, it's usually easier to use a more standard sling or cordelette style anchor, because you have a single master point.

If you are going to use a rope anchor as described here, and are not changing leads, typically climbers will swap the ends of the rope at every belay. The easiest way to do this is to connect your harness to the rope ends with a figure 8 on a bight knot and two stout locking carabiners, rather than the standard rewoven figure 8 knot.)

Rescue geeks, I can hear you now: “But how are you going to escape the belay if you need to rescue your partner?” The answer is, yes, it’ll be a little more difficult, but you can do it. But, here’s a question to ponder - have you, or anyone you personally know, ever had to actually do this in real life? Climbers who use this method generally feel the simplicity, weight savings and lower cluster factor of tying in directly with the rope outweigh highly unlikely rescue scenarios.

There are many other options for using the rope to tie in directly. We cover one in another article, using just clove hitches, read about it here.

Here are two different knots you can use to tie directly to a two piece anchor.

1 - Bowline on a bight

This is my preferred technique. This is essentially a bowline knot with two loops rather than one. The knot is easy to learn, fast to tie, and easy to visually inspect to see if you did it right. You can adjust the size of each ear to equalize the anchor.

Typically, bowlines are not popular with many rope professionals for securing the end of a rope, because the knot can loosen up unexpectedly. However, in this application the bowline works fine, because the end is secured to your harness and can’t possibly pull through the knot.

John Long tried to popularize this in one of his rock anchor books about 15 years ago, but it never really seem to catch on. Too bad, it's a great knot. Maybe it was the cheesy name I think he gave it, the “atomic clip”. Just call it a bowline on a bight; that’s the common name and describes it perfectly.

Here’s a video showing how to tie a bowline on a bight.

Here's what it looks like, from the leader’s point of view.

You can clip your belay carabiner to the shelf (both of the loops to go to the bolts) to bring up your partner.

2 - “Bunny ears” Figure 8

This is a variation on the figure 8, familiar to every climber. This might take a little practice to tie neatly with no twists, and to get the length of the loops correct. This knot is popular with professional ropeworkers, who use it to secure one end of a fixed rope. (Tip: start with a larger bight than you think you need to, at least 2 feet.)

This knot has a cool feature of being able to slide the “ears” to two different lengths, to accommodate one bolt that may be a little higher than the other. This is actually sort of magical, you just need to play with it to see how it works. You need to do this when the knot is relatively loose. After you snug it down, the “slide” feature does not work.

One more thing: some people think that the bunny ears figure 8 is not redundant, meaning that if one strand were to be cut, it could conceivably pull through and the knot would fail. This has been tested many times and does not happen, so yes, the knot is redundant.

Here's a short article that covers it nicely, from Australian rigging expert Rich Delaney and Ropelab.

Here’s a video showing how to tie a bunny ears figure 8, by expert climber Beth Rodden. (She calls at the “super 8”, same thing.(

Here's what it looks like, from the leader’s point of view.

Same as with the bowline on a bight, you can clip your belay carabiner to the shelf to bring up your partner.

"Triple locking" carabiners

What’s a “triple locking” carabiner, and why might you want to have a few? Well, pretty much every arborist or industrial rigger has a few on their gear rack, so you might want to get some too. There are some pros and cons to this style of carabiner, plus a trick to easily open it with one hand.

A triple locking carabiner (also known as a “3 way”, “twist lock”, or “triple action” or a “tri-act”) can be a good choice for certain climbing uses. (And, not such a good choice for others . . .)

The idea: there are three separate actions that are required for the gate to be opened. Typically, that’s 1) sliding a metal sleeve, 2) twisting the metal sleeve, and then 3) opening the gate.

These carabiners are common in rock gyms, climbing schools, industrial rigging, high rise window washers, mountain rescue, arborist work, and with Professionals Who Do Dangerous Things Far Off the Ground, so that ought to tell you something about how safe they are.

But, safety does not always mean ease of use. Let's read on.

The Petzl William is a triple locking belay style pear-shaped carabiner.

image - moosejaw.com

The Petzl Am’D is a more all round “D” shaped carabiner.

image - moosejaw.com

Twist lock carabiners have some nice features . . .

1 - When the gate is closed, you know that the carabiner is locked, and that’s it’s very likely going to stay that way. With a normal screw gate locker, there is always that little nagging background voice that asks “Well, the gate is closed, but is actually locked? And, if the gate rubs against the rock or some other weirdness, is there a chance it could unlock itself accidentally?” If you use a twist lock carabiner, those two concerns are much gone. This makes them a good choice for beginner climbers, because you can be pretty much sure it's going to work as intended, without reminding the beginner all day long to be sure and lock the carabiner. That's one of the reasons guides like to use them for clients.

2 - It’s easy to open the gate even after the carabiner has been severely loaded. If you put a big load on a standard screw lock carabiner, tighten the gate, and then unload the carabiner, sometimes the screw sleeve locks in place and it can be tricky to open. No such issue with a twist lock.

They also have some not-so-nice features . . .

1 - They are not well-suited for snow/ice climbing, because A) they can be difficult to open if you're wearing gloves, and B) bits of snow and ice can get stuck in them, causing them to fail in various ways. (Yes, people have been known to pee on their carabiners to get them open, but I don't have a video tutorial on that one yet. =^) The same concern applies to dirt and mud, so probably not so great for caving and canyoneering, but I don't have any direct experience with this.

2 - They can be tricky to open with one hand. Often it's helpful, especially at a more complicated belay, to be able to operate a carabiner easily with one hand. There is a bit of a trick to doing so: Hook your ring finger in the bottom of the carabiner to apply a little downward pressure, and then use your thumb and index finger to slide twist and open the gate. Like most things in life, pretty easy once you know how.

Here's a quick video I made showing the technique.

3 - They are a bit heavier and more expensive than a standard screw gate. Below: Petzl Am’D 79 grams, Black Diamond screw gate, 55 grams, difference of 24 grams. Probably not a dealbreaker for most people, but if you're a lightweight nerd, it might be a consideration.

So, what's the best use for twist lock carabiners?

Should you use them for every part of climbing that requires a locker? No.

Like almost all aspects of climbing, it comes down to personal preference, so here's mine: When you absolutely positively want it 150% bomber.

Setting up top ropes or fixed lines in an instructional setting where you’re not around to keep an eye on them.

Various things on big walls, where large loads hanging at strange angles and super-secure connections become more common and important (such as fixing the rope for the second to ascend, connecting a tag line onto the haul rope, or connecting haul bags to each other and the haul rope.)

Making a carabiner block, so you can rappel on a single strand. (This is an advanced technique for canyoneering and crafty climbers that I'm not going to cover right now, but you can Google it.)

Here's the easy solution: buy one and see how it works for you.

One other option - try the more modern flavors of auto locking carabiners. I'm not going to try to summarize them here, but many of these have some innovative designs to try to address some of the problems with twist locks mentioned above, such as not working well in the snow, or being able to open them with one hand easily. I have both of the carabiners below and they work great.

If you want to read more about this, here’s a good summary of the different flavors of auto locking carabiners.

Black Diamond Magnetron. Clever design uses magnets to keep the gate closed. Easy one hand opening, works with snow and ice.

Edelrid Slider HMS carabiner. A nice belay carabiner, easy one handed opening, works well in snow and ice.

Locking carabiners for sport anchor quickdraws

A majority of sport climbers are fine with using two standard quickdraws for their anchor. Most of the time, that's probably cool, but for instructional settings or your own peace of mind, you can go one step further and use lockers on everything.

A standard anchor for many sport climbing areas is for the leader to just clip two standard quick draws to the bolts and lower off. This is certainly safe enough in most situations, and the fact that it is been done literally millions of times without incident should probably tell you that it's an acceptable practice.

Having said that, many people prefer at least one designated “locker draw” as part of the anchor. If you’re in an instructional setting, with many people top roping off the same unattended anchor all day, without a more experienced person going up regularly to check things, locking carabiners can add great peace of mind. Because it's a top rope, you’re not right there next to the anchor to see if any carabiners are getting cross loaded, gates getting unscrewed, or other strangeness that could lead to an anchor being compromised.

(Sidenote: there are lots of other handy uses for having a locker draw, you can learn them here.)

Personally, I have two designated quickdraws just for anchor building. They are the Petzl Express 25 cm long draws, the longest they make, and four locking carabiners. Each pair of carabiners is distinct, so I know which is for the rope and which is for the bolt. The longer 25 cm draw gives a nice narrow angle on the anchor if the bolts happen to be a bit far apart.

This is an easy and inexpensive set up. You probably already have a few extra locking carabiners around, and the long “dogbone” draws are only $5-$6 apiece.

If you’re inclined to be a little more cautious, using lockers on your sport anchors can be a little extra insurance, with low cost and high confidence factor. Look at it this way: Other climbers might call you a little paranoid, but there's really not much downside to doing this. You need four carabiners for the anchor at a minimum, why not make them all lockers? There's a slight increase in cost and weight, but one top roping that should not be much of a concern.

“I don't want to climb with that guy, he's too safety conscious.” That's the kind of criticism many people don't mind hearing. =^)

As we like to say here at Alpinesavvy, it's YOU who’s accountable for your level of comfort and acceptable risk. It doesn't get to be dictated by anyone else, regardless of their experience or credentials.

Two standard quickdraws with non-locking carabiners. Bottom gates opposed and opposed. Nothing wrong with this setup.

Now, we have a locker draw in place of one of the regular quickdraws. Definitely a bit more security here. (The angle of the rope running through the carabiners will going to add a bit of friction, but it's still acceptable.)

Here’s an alternative. Similar setup, this time with 4 lockers. Nice long dogbones, round stock carabiners at the bottom for a smooth rapport, and super secure. Which set up would you prefer to climb on?

Are you more likely to get lost going up or going down?

Are you more likely to get lost when you are climbing up a mountain, or heading down?

Quick question: Are you more likely to get lost going up a mountain, or on your way down?

Answer is: going down. This is true for several reasons.

Terrain features like ridges and gullies diverge you go downhill away from a summit, magnifying the mistake of choosing the wrong feature.

On the way down, you’re physically and mentally more tired, so you're more prone to navigation errors.

Returning to your last known point (usually the best way of getting unlost) usually involves going back uphill, which sucks. It's easier to keep going down, which can turn slightly lost into completely lost.