Alpine Tips

Cordelette - Connect the ends with an overhand knot

Yes, every climbing instruction book tells you to use a double fisherman's knot to tie your cordelette into a big loop. Guess what: the overhand knot works fine.

Yes, an overhand knot. Yes, the same one you use to tie two ropes together to rappel. (If you want to get technical it's a “flat overhand bend.” previously known as the Euro Death Knot, of EDK).

Or, to really keep it simple just carry your cordelette completely untied, also known as an “open” cordelette.

Tie a small overhand loop in each and, a.k.a. bunny ears style

Want a traditional big loop? Tie with a flat overhand bend.

Hey, if you're happy keeping your cordelette pretty much permanently tied into a loop with a double fisherman’s knot, feel free to keep doing it that way. But, if you see somebody tying a cordelette as shown below, don't freak out about it, it's fine.

Just like if you were using it to connect two rappel ropes, make sure you've got a nice long tail at least 6-8 inches, and make sure the knot is “dressed and stressed” - properly snugged down

Update: a reader mentioned on a related Instagram post that if you’re using a 5.5 mm HMPE “tech cord”, at least one manufacturer recommends using a triple fisherman's knot to tie a loop, because this material is more slippery than standard cord. So, if your cordelette is made of tech cord, probably best to avoid the flat overhand bend.

Note the striking resemblance to the Flying Spaghetti Monster . . .

Knot close up: Yep, that's your garden-variety flat overhand bend. (And please don't call at the European Death Knot (EDK), we're trying to get away from that, okay?

Hey, don't take my word for it. Here's a photo of an anchor made by IFMGA Guide Dale Remsberg, taken March 2019. Notice the flat overhand bend connecting the cordelette ends.

and, in an email to me from internationally certified guide Rob Coppolillo, and co-author of “The Mountain Guide Manual”:

“I have my cordelettes tied with flat overhands right now....and I'm liking it. Easier to untie, etc. Only time I do not leave it tied as such, is what I'm using the cord as one big loop (as in, not tying it off as a distributed, redundant anchor material).

Indeed, the flat overhand starts rolling at relatively low loads, but in the testing I've seen it rolls once or twice, then quits....unless of course the load stays on it indefinitely.

Does this make sense? So, I guess I'd say, go for it with the flat overhand...but if you're using the cord as one big loop, maybe take the time to tie a double-fisherman's, if you foresee high loads.“

And, one more endorsement, this time from a video made by Ortovox and the German Mountain and Ski Guide Association - some folks who know what they're talking about. In this video about building multi piece gear anchors, he says at about 2:20: “I fix the optimum height of the anchor by tying an overhand knot (in the open cordelette).” Screen grab below of overhand knot; See the video here.

Lowering a climber - reasons and methods

There are times when lowering, rather than rappelling, is a smarter way to get down a route. Learn of some of the scenarios when this might be a smart move, and several common ways to set it up.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of an experienced climber, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

Scenario:

You and your partner have topped out on the classic West Ridge of Forbidden Peak in the Washington Cascades. Now it’s time to descend; a series of short rappels and down climbing the low 5th class ridge. Problem is, the wind is ripping and you see all kinds of rope-eating blocks ready to entangle your rappel rope if you toss it in the normal manner.

This is a good time to think about lowering your partner.

If the first climber down is lowered on one strand, with the other rope end clipped to a locker on their belay loop, there is minimal chance of the rope hanging up anywhere, causing a spaghetti pile halfway down, or blowing into some rope-eating rock crevice.

Lowering can also be a Good Idea when:

If you have an injured climber who might be unable to rappel on their own.

Climbing with a beginner who may not know how to safely rappel.

You're climbing at an area that has good access to the top of the cliff (Ouray Ice park, for example), so you can lower the first person to get the rope down.

Someone dropped their belay device, whoops.

Someone wants to take another lap on the route, or try the crux moves a few more times.

Climbing teams below you who might get annoyed if you suddenly drop a rope on their head.

More efficient descending: You and your partner climb a two pitch route. If you can lower one person to the ground from the top of the second pitch, then the second person can make two rappels. (If you're counting, that's one lower and two rappels, instead of four rappels.) In certain circumstances, and depending on the skill level of your partner, this might be faster and decrease the risk.

If you’re rapping into unknown terrain where the location of the next anchor is uncertain. If the next anchor down is farther than half of your rope, you need to do some crafty rope tricks to get there. It's much better to figure this out while you’re on a safe top rope than from dangling at the very end of your rappel ropes! The first person down may need to pendulum to locate a good anchor spot, and this is much easier to do when you can use both hands. Also, If the first person down is lowered a little too far past the anchors, hopefully they can climb back up on belay, rather than doing a rather complicated rope trick of transitioning from rappel to ascending the rope. Communication between partners is of course very important when doing this. Consider using hand signals to avoid yelling.

Notes:

This is best done with a single rope rappel.

The climber being lowered can bring both ends of the rope with them as they are lowered.

Communication needs to be rock solid between the partners, because of course you don’t want to lower the first climber past the anchor. But on many alpine routes you want to be doing short rappels anyway to minimize the possibility of a rope getting stuck, so communication is often easier because you’re closer together.

Lowering is best used when you and your partner can clearly see one another.

Avoid having the rope run over any sharp edges.

Using an autoblock third hand backup is strongly recommended.

Remember to close the rope system by having the top climber tied in to the end, or at least a solid stopper knot.

Having a middle mark on the rope is especially helpful so you (hopefully don't have to) lower them past halfway. If your rope does not have a clear middle mark, find where it is by flaking from the ends and slap on some tape to make a temporary one.

Here are several common ways to rig a lower:

Munter hitch

Redirected plate device

Redirected Grigri

1 - Munter hitch

Probably the simplest way is to tie a Munter hitch on the anchor master point and lower off of that. Add an autoblock friction hitch to the brake strand and attach it to your belay loop as a “third hand” backup. Note that lowering from a Munter hitch can put some mean twists in your rope! To help minimize this, try to keep the brake strand parallel with the loaded strand.

Photo: Left, good technique with the load strand more or less parallel with the brake strand. Right, holding the brake strand out to one side can introduce twists to your rope.

2 - Redirected plate device

This is slightly more complicated to set up, but offers solid advantages. No rope twist. Excellent friction and control. No pulley effect increasing force on the anchor. Easy to lock up and go hands free if need be. And, although it looked like it might twist your rope, it (generally) doesn't.

Let's look at a few different ways to rig a redirected plate.

Here's one of the simplest. Because the device is oriented downward, we have to redirect the brake strand through something, otherwise you're just running a rope around a carabiner with zero added friction.

(Side note: if you accidentally clip the LOAD strand rather than the BRAKE strand back into the carabiner, your mistake will be instantly obvious as the device will get sucked up into the carabiner and do all kinds of weirdness. You’ll probably only make this mistake once . . .

It's easiest to simply take the brake strand and clip it to some higher component of the anchor. A third hand auto block, clipped to your harness, is a highly recommended backup.

I find it easiest to set this up by holding the belay device in front of me (just as if I were lowering someone off my harness) threading it with the load strand on the correct side, and THEN clipping the device onto the anchor.

Note: if you're redirecting it to the shelf of an anchor, be careful that the moving rope is not running over sling or cord.

If you're short on locking carabiners to redirect the strand up high, or the anchor does not have a convenient higher clipping point, you can also use the same carabiner that the device is clipped to, as shown in the photo and video below. (This can misbehave a little bit depending on which strand of the tube the rope goes through, the shape of the carabiner, and a few other variables. I recommend practicing with this one a lot if you think you want to use it, and as a first option, go with the method shown above.)

Here’s an Instagram video by AMGA certified Rock Guide Cody Bradford that shows the method.

Here's another way to rig a redirected plate device - with am offset quad anchor. This is tied like a regular quad, only with a pair of loops at two different heights rather than having them all the same height. With this offset, it gives you a perfect place to clip your file plate on the lower loop, and the redirect carabiner on the upper loop. Learn more about the offsite quad here. Here's a photo from the article:

Here's an efficiency tip: If you’re lowering the first person from a rappel anchor and the second also needs to rappel (which is highly likely), you can save time by pre-threading the rope through the hardware, and then setting up the redirected lower. By doing this, when the first person has reached the lower anchor, the second person will already have the rope threaded and be ready to go on rappel.

Note how the belay device is attached to the carabiner. You clip the rope through the device just like you were belaying from your harness. You do NOT set it up in guide mode, like you would to bring up your second.

At first glance, you might think this is wearing out the anchor hardware, but that in fact is not the case. All of the load is on the belay device, and the brake strand without any tension is passing through the hardware.

Here's a short Instagram video on how to set this up from AMGA Certified Rock Guide Cody Bradford. (I can’t embed this on my website, you'll have to use the link.) In the video, note the very Crafty Rope Trick of using the backside of the leaders clove hitch to connect the second, which enables their rope and to be untied and threaded.

Here's a nice video from Smile Mountain Guides showing the redirected plate lowering technique. (Start at about 8:10.)

3 - Redirected Grigri

The redirected Grigri works on a similar principle to the redirected plate. The brake strand must be redirected through some higher component of the anchor to provide adequate lowering friction.

If you’ve seen the odd looking Petzl “Freino” carabiner, and wondered what it's for, this is it - an easy additional friction point. If you’re guiding and lowering people from a Grigri a lot, it might be worthwhile to get this specialized and expen$ive carabiner. (I don't have one, so no action photos.)

image: https://www.rei.com/media/product/716219

For the rest of us, you can do the same thing with a simple redirect - here, with the brake strand clipped through the wire gate carabiner. Be sure and rig the Grigri so the handle is facing out from the rock, and the camming action of the Grigri is not impeded by rubbing against the rock.

A slick way to build an anchor from the rope

Making an anchor with only the rope and a few carabiners can be a very useful skill. Here’s a Crafty Rope Trick (CRT) that does this with just a few carabiners and knots you already know.

There are lots of ways to build an anchor with just the climbing rope. You could use a bowline on a bight, or a “bunny ears” figure 8, as discussed in this post. Either of these gives decent load distribution, but they do require that you learn new knots that some people find a little tricky.

Here’s a slick method to make an anchor with the climbing rope that simply uses clove hitches and a butterfly or overhand knot, which you hopefully already know. (If not, check out the video section.)

One good reason for using the climbing rope as your anchor: if the climbing is tough and run out right off of the anchor, and thus a greater chance for a leader fall to put a large amount of force onto the anchor and belay. Having the entire anchor made out of dynamic rope gives more stretch to the system and will lower the force on all the other components.

There are a few downsides to rope anchors:

It works best if you’re swinging leads on a multipitch climb. If one person is doing all the leading, or if this is the last anchor at the top of a climb and you’re transitioning to rappel, it’s better to craft an anchor from a sling or cordelette so you have both ends of the rope to work with. (Even if you plan on swinging leads, your partner might decide they don't want to take their turn and you might have to go again, so keep that in mind.)

If the next pitch is a real rope stretcher and you might need every bit of it, this may not be the best choice.

When the leader pulls up the rope on the second, the rope pull come tight first onto the anchor and not directly onto the second climber. This can create a few meters of potentially unwanted slack when the second breaks down the anchor. The second can clip in to one bolt or piece of solid gear with a tether before they remove the anchor as a possible solution.

Rope anchors can make any sort of self rescue technique more challenging, because the end of the rope is a component of the anchor. Yes the belayer can can simply untie and they're out of the system, but then they’ll have a harder time using the rope for much of anything useful.

Say you’re leading, and arrive at a two bolt belay anchor. Here’s what you do.

Clove hitch the rope (that’s tied to your harness) to a bolt with a locker. Clip a second locker onto the second bolt.

Maybe 6-8 inches inches on the “backside” of this clove hitch, tie a bight knot. Here I tied a butterfly knot, but it could be an overhand or figure 8 on a bight.

Next, clove hitch the rope to the second bolt. Adjust the clove as needed to center the loop.

Clip a plaquette style belay device to the butterfly, and bring up your partner.

Done! You’re connected to both bolts, and you have an equalized master point. You hopefully set this up in under one minute, and used a minimum amount of gear.

Monkey Face - base jump and king swing videos

So, this isn't technically rock climbing, but these two short videos will get your blood pumping. Alternative ways to scary yourself on the iconic and amazing central Oregon rock feature, Monkey Face.

Okay, so this is not really rock climbing, but it's pretty darn fun to watch some alternative ways to enjoy the famous Monkey Face at Smith rock Oregon.

The videos here for entertainment purposes only, and Alpine Savvy does NOT recommend that anyone try these Monkey Face shenanigans.

and the King Swing. Action starts at 1:00. Note - there was a serious accident in 2011 related to doing this swing. Please don't be involved in the next one. I don't recommend that anyone try this. But if you do, be sure and wear brown pants =^).

Use a “gear closet” on a big wall

Where to keep that #4 Camalot you’ll need 3 pitches ahead? Answer: gear closet.

On a long pitch, a leader may not want to take the entire rack of gear with them. Or, your route may require some extra large cams higher up, but not on the lower pitches. So, the question: what do you do with the extra hardware? The place you probably don’t want it is buried down in a haul bag, making it hard to access. (It’s good practice to minimize the amount of time you spend burrowing through your main haul bags during the day.)

Instead, try this. Get a Fish Beef bag, size large, or similar heavy duty stuff sack. Girth hitch an old-school sewn loop daisy chain into the sturdy loop of the bag.

Clip your extra gear to the daisy loops. Never put loose, unclipped gear into the bag, because the chances of dropping it are huge. The leader can add and subtract gear from this “gear closet” bag before they start the pitch, or they can use a tagline, trailing a small diameter tagline and hauling up gear as it’s needed. (Tagging is a great approach on a long pitch, because you start with a much lighter and easier to manage rack.)

You can keep the gear closet on a gear tether hanging from the main haulbag, if you really trust the tie in points, but most folks will probably want it inside the top of the main haulbag.

Wilderness trip planning, start to finish (video)

There are some fantastic navigation resources online, but it can be confusing how to use them most effectively and where to get started. Watch this video to see one way to plan a climb, from start to finish.

There are a bounty of amazing navigation resources available to the backcountry traveler. Generally, this is a good thing, but it can also be a little overwhelming. What app to use? Where do I start? How do I print free maps? And maybe more specific questions, like:

I found three different GPS tracks for the trip I want to go on, which one should I use?

How can I make a map with the GPS track printed on it?

How can I get the GPS track into Google earth to scope out my route before I leave home?

What's the best way to get the GPS track onto my phone so I can use it with Gaia GPS?

I don't have a track file, but I have a pretty good Idea of where I want to go. How can I draw this track in on a map, print it, and get it onto my GPS?

If you’ve ever found yourself scratching your head with questions like that, we've got you covered with the video below. It covers most every aspect of wilderness trip planning - searching online to find a GPS track for a climb, opening and editing the track in Caltopo, exporting and opening in Google Earth, printing the map, and exporting the GPX file to your phone.

(Hint, parts of the video are best viewed in full screen.)

Headgear for climbers

There are lots of different options when it comes to headgear. One can even keep you from a coughing attack.

Some people have a glove fetish. Me, I’m more of a hat guy. Here are a few different flavors of hat you might consider for your next climb.

Sun hat with a visor (and neck protection)

If you’re in open snow terrain (especially on a south facing NW volcano route) you’re in a giant solar reflector oven. Heading downhill back to the trailhead you’re going to want some shade on your eyes and very possibly coverage for your neck. I’ve noticed a lot of the guides on Mt. Rain-here have the Outdoor Research Sun Runner hat. It is a little spendy, but it’s quality gear.

Balaclava

“Baklava” is a tasty middle eastern dessert that goes in your mouth, not on your head.

“Balaclava” is a hat that tastes terrible. But should always be in your pack, as it’s pretty much the best bang for your buck when it comes to warmth and weight. This should be standard emergency gear for just about anyone, and generally part of your 10 essentials kit of extra clothing. Get one that’s thin to medium weight so it fits underneath your helmet. It does not need to be name brand from the outdoor store. Costco, of all places, has a terrific one on sale at this writing (Jan 2019) for just 10 bucks. It’s made by Bula, from soft stretchy fleece, and can be worn in lots of different configurations. Recommended.

Online these appear to be $20, they are $10 each at Costco.

Ear warmer

This is just a band of stretchy fleece that covers your ears and keeps the top of your head exposed. On cold windy approaches, it’s nice to vent some heat from the top of your head, but still have your ears covered so you don’t get an earache. For me, this seems to be especially true in early mornings on Mt. Hood.

There are loads of Inexpensive ones at the online retailer that starts with “A”. Search for “ear warmer headband”, you’ll find a bunch. Here’s a photo and a link to one I have that works great. Also good for cold bicycle rides, as it fits nicely under my helmet. Get one in a fun color.

Neck warmer

Having just a bit of coverage on your neck can make a surprising difference in staying warm. It’s a tube, so you can clip it to a carabiner. For chilly morning or routes in the shade when a balaclava may be too much and a buff not quite enough.

A balaclava does pretty much the same thing, but is a bit heavier and bulkier.

Buff

OK, this is not really a hat, but it can have a place on outdoor trips, especially high altitude treks and climbs. A friend of mine recently returned from a climbing expedition to Nepal. A very common problem with high altitude climbers is known as the “Khumbu cough”, a hacking awful cough that usually starts with sucking a lot of cold dry air. She told me their expedition leader was adamant that people breathe with a buff over their mouth pretty much all of the time, and a balaclava covering their mouth at night. This creates a higher humidity environment right around your nose and mouth, which can dramatically cut down on dry cough and hack attacks. And she said it worked great. Simple solution for a common problem.

A buff can also be worn combined with a balaclava in super cold conditions, And it can replace a balaclava in mild conditions.

image: https://www.alpineascents.com/blog/gear/buff-101/

Video - Metolius cam vs 1 ton boulder

I think this is my new favorite climbing video, and it doesn't even have a climber in it. One more reason to love Metolius gear.

So, this might be an old one for some of you, but I just found this video and think it's pretty awesome. (It’s only 1:36, so yes you have time to watch it.)

I love the thought process behind this video.

“Hmm, here we are on the farm . .

I have this old cam . . .

Here's this giant rock . . .

I've got this angle grinder I can use to cut a groove in the rock . . .

and look, here's a tractor!”

One more reason why I love Metolius Gear - Made in Bend, Oregon, USA!

2 tips for hot weather big walls

Headed to Yosemite or Zion in the summer to try a big wall? It’s gonna be HOT! Here are two lightweight and inexpensive things to bring to make your vertical camping trip a little more bearable.

This tip come from big wall expert Andy Kirkpatrick. Check out his excellent book on big wall climbing, “Higher Education.”

Yosemite valley or Zion in the summer can be a reflector oven on a big wall. If you find yourself in the heat, here's two easy ways to stay a bit cooler.

small folding umbrella

water mist/spray bottle

Between some instant shade and evaporative cooling, you can stay a lot more comfortable at that multi-hour belay.

And, that will give you some time to think about why most people like to climb in Zion and Yosemite Valley in the spring and autumn. :-)

If you're in Yosemite in the summer and want to climb, consider heading to the higher elevation Tuolumne Meadows area.

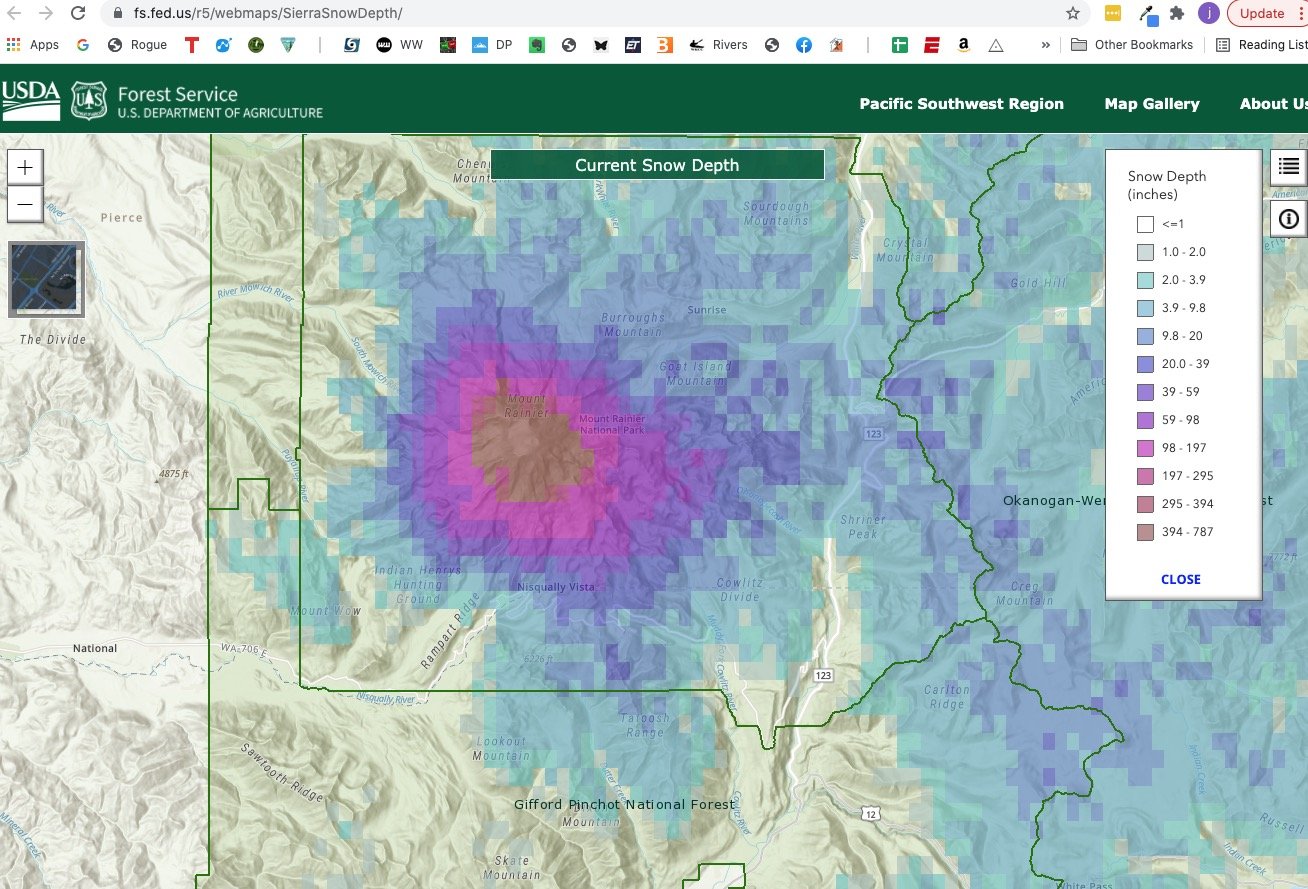

Real time snow depth map of USA and Canada

Want to know the amount of snow on the ground anywhere in the US and most of Canada? This is your go-to website. This interactive map from the US Forest Service is easy to use, understand, and shows real-time snow info for your trip planning.

When planning a backcountry trip (or even a long winter drive) it can be very helpful to know real time snow levels. Is the trailhead snowed in? Should I bring skis? Should I prepare for camping on snow, or bare ground? I heard it's really dumping in Utah, how much snow do they have? Is driving on the interstate across Wyoming in January going to be a bad idea?

The US Forest Service had you covered, with a very cool snow depth model (repeat, MODEL).

From USFS: “This map displays current snow depth according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Snow Analyses (NSA). The NSA are based on modeled snowpack characteristics that are updated each day using all operationally available ground, airborne, and satellite observations of snow water equivalent, snow depth, and snow cover. “

A few notes:

Works better on a desktop with a nice big screen.

Seems to default to dark mode on the map; if you want normal view click on the map icon on the left.

Possible software bug note: Apparently the USFS server will stop serving you snow depth tiles if you request too many of them, lame . . . If you pan and zoom a lot, the colored snow depth information may disappear from your map. So, try to stay in one area. Or maybe change to a new browser.

Government websites have an annoying habit of regularly changing URLs and breaking links. If the button below doesn’t work, do a web search for “USFS snow depth map.”

Here’s a screen grab - Mt. Rainier National Park, November 2021

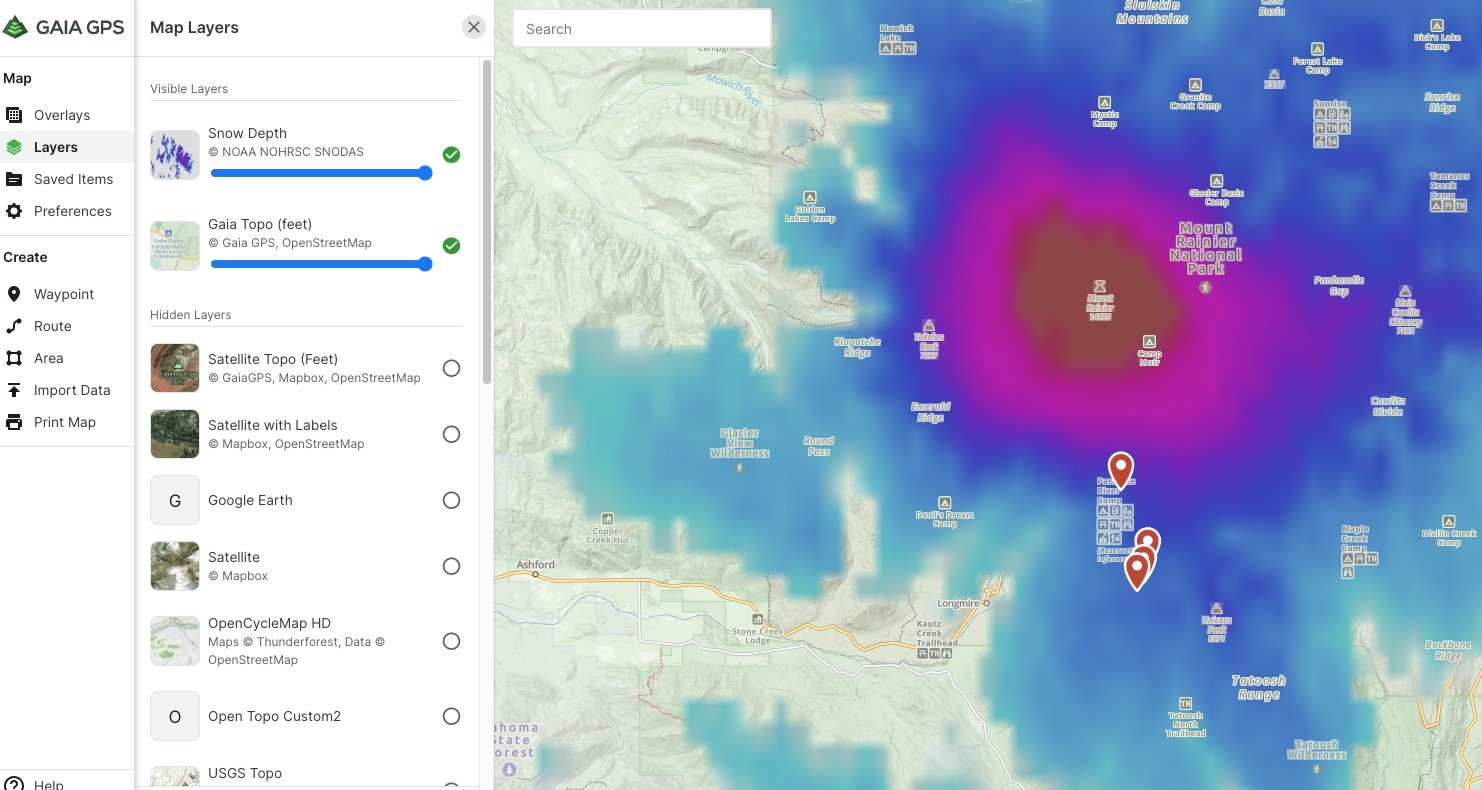

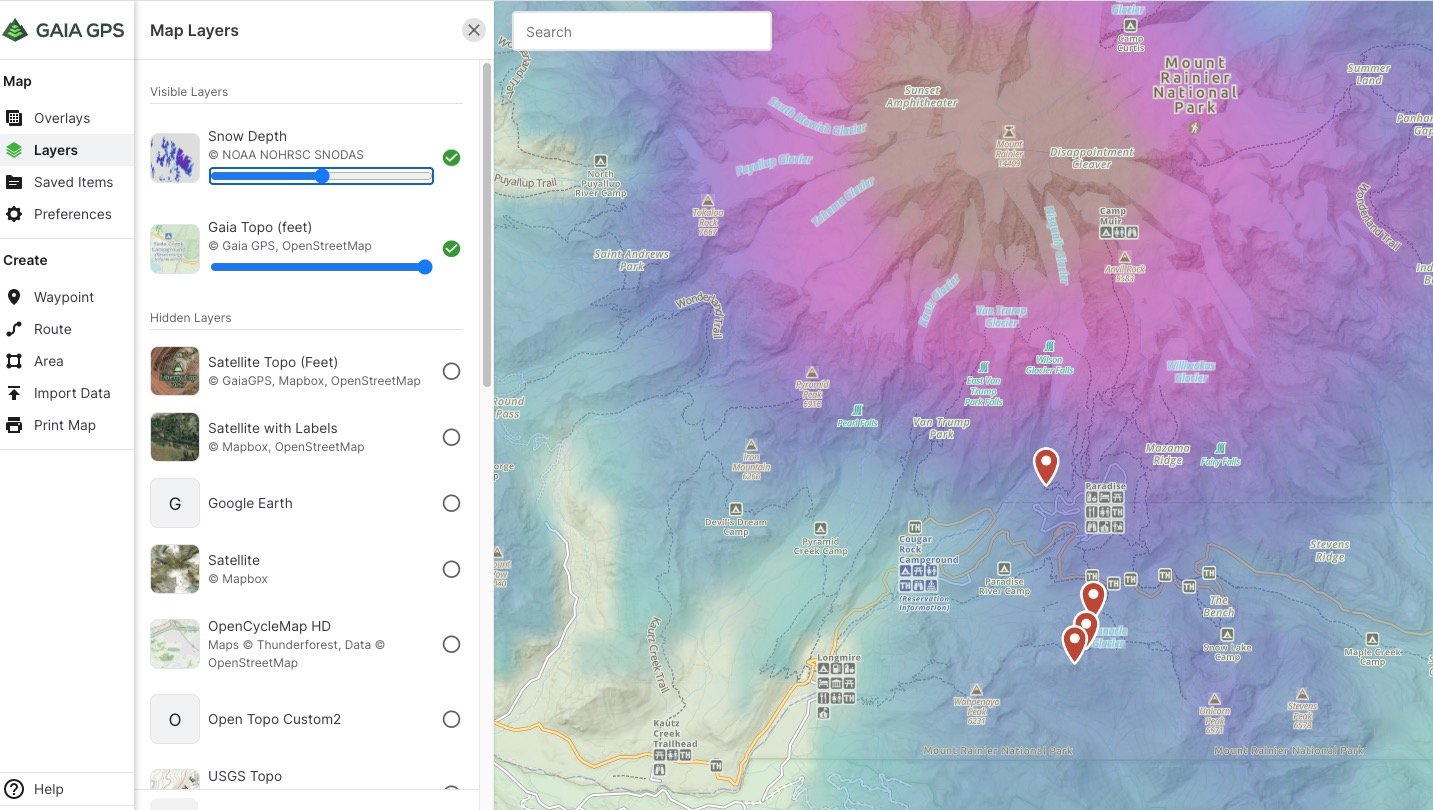

If you're a Premium subscriber to Gaia GPS, you can also get the same data in a more usable format. Gaia lets you change the opacity of various map layers, showing details of whatever base map you choose. You can also have a GPX track of your intended route on your map, so you can more clearly see whether your planned trip involves lots of snow or not.

Here's a screen grab of the snow depth data laid over the top of the Gaia Topo default map layer. Note the slider bar on the left, opacity is at 100%. Yes, it looks a bit hideous, but you can clearly see exactly where the snow begins.

Now we've zoomed in a bit, and changed the snow depth slider bar to around 50%. Now you can see underlying roads and trails. A bit more helpful if you want to do some hiking.

How to rig a "courtesy" anchor

Extending a rappel anchor master point over a ledge can make for an easier rope pull, but a tougher start to the rappel. Rigging a “courtesy anchor” can make things easier and safer for just about everyone. (Sorry there, last person . . . )

This tip comes from my pal and canyoning expert Kevin Clark. Check out his excellent book, “Canyoning in the Pacific Northwest: A Technical Resource.”

A “courtesy anchor” is a concept from the canyoneering world, where generally a LOT more thought is given to rappel technique than is typical in rock climbing. It’s not something you’ll rig very often, but in certain situations it's a very #CraftyRopeTrick to have in the toolbox!

Imagine this scenario: -A rappel anchor has a long extension on it, maybe webbing or chain. The purpose of the extension is to hang the anchor master point out over the cliff edge, making it easier to pull the rope. The problem: this probably will make an awkward start to the rappel, because the master point is hanging out into space rather than being on on the actual anchor, which is set back on a nice flat ledge. (In the Portland Oregon area, the rappel off of Rooster Rock in the Columbia River gorge is a great place where you can use this technique.)

The “courtesy anchor” is a simple solution. The main benefit: only one person on the team (ideally the person with the most experience, who goes last) has to perform the awkward rappel start. Everyone else can begin their rappel at the actual anchor point, away from the edge of the cliff. There’s no need for everyone on the team perform an awkward / dangerous / difficult start to the rappel.

There are various ways to rig this. Here’s one of them.

Add a carabiner onto the upper anchor point, and then bring the rappel master point back and clip it to this added carabiner.

This allows every person but the last to start their rappel on a nice flat ledge rather than shimmying over the edge. The last person to go, hopefully a more experienced and skilled climber, removes the courtesy carabiner, extends the master point to its original position, and makes the awkward start to the rappel.

The last person has a few options to reduce their risk.

Get a firefighter’s belay from below

Lock off their rappel device with a mule knot (or similar)

Tie a hard backup (aka catastrophe knot) / overhand loop with both strands of the rope, about 10 feet below the edge, and clip that to their belay loop

Put a klemheist knot or some other friction hitch that is releasable under load above their belay device

Or some combination of the above

If all goes as planned, this makes a faster and safer rappel for just about everybody. Except the poor suckah’ who has to go last . . .

Here’s how it works.

This anchor as shown is great for pulling the rope because it extends the master point over the cliff edge. But it can be awkward to start your rappel.

Clip a locking carabiner to some point on the orange cordelette. There are several places where you could clip, here I’m using the shelf.

Another option is to basket hitch a long sling higher up on the tree, assuming the tree is strong to handle the increased leverage. (Having an attachment point higher up makes it even easier to start your rappel.)

Pull the rappel masterpoint quicklink up, and clip it to the locking carabiner. Doing this allows everyone except the last person to start their rappel right at the anchor. The last person removes the sling and carabiner, extends the master point to the edge of the ledge, and performs the somewhat awkward rappel start, leaving the rope in a better position for a successful retrieval.

Finally, here's a nice video by canyoneering expert Rich Carlson showing a few different ways to rig it.

How to rack your aiders

Aid ladders always seem to be trying to trip you up. And when you're free climbing, you have to keep them tidy and out-of-the-way, but instantly accessible to transition back to aid. Here's a great technique to do just that, from expert climber Libby Sauter.

This tip was shown to me by Libby Sauter, expert climber and holder of the women’s team speed ascent of the Nose on El Capitan. Thanks Libby!

A good rule of thumb for just about any kind of climbing is never have anything hanging below your knees. So, what to do about those pesky aid ladders that always want to trip you up, when you're either gearing up at the base of the route, or transitioning between aid climbing and free climbing?

Here’s a crafty way to quickly roll up your aiders to get them out-of-the-way, yet make them instantly accessible to unroll when you need them. And if you do it right, there won't be any twists.

Take the second step of your aid ladder, and pass the hero loop under the step.

Repeat with the fourth step of the ladder, and again with the sixth.

Finally, clip the hero loop onto your aider carabiner. This should be a designated carabiner that always lives on the business end of your aiders.

You should have a nice compact bundle, looking like the photo below.

To deploy, just unclip the hero loop from the carabiner, and give a shake. The aider should fall down untwisted, ready to climb.

It’s a better show than a tell. Here’s a short video showing how it’s done.

Hauling directly from a Traxion pulley

Connecting your haul rope to the haul bags with a Micro Traxion (or similar progress capturing pulley) can make your life easier in a lot of ways. (Thanks to big wall expert Mark Hudon for this tip.)

Credits: This system is also known as the “far end haul”. I believe it was originally invented by legendary Yosemite dirtbag Chongo, and shown to me initially by Mark Hudon. Check out Mark’s great website for more on this.

Note the haul line going directly to the Petzl mini Traxion.

(Also note the haul line clipped in with a locker to the top part of the swivel as a backup.)

image: mark hudon

The traditional big wall set up to rig your haul rope to the haul bags is to pretty much connect them directly, something like this:

Figure 8 on a bight (or better yet, a butterfly knot, easier to untie after loading) on the end of haul rope

Locking carabiner

Swivel (optional but highly recommended)

Another locking carabiner attached to haul bag(s)

However, with the addition of just one more piece of (admittedly expensive) gear, you can make your life a whole lot easier in certain situations. All you do is add a progress capturing pulley, (aka PCP) like a Petzl Micro Traxion, to the locking carabiner upstream from the swivel, put your haul rope through that. Note that you set this up on the ground from the very first haul, and keep it on the system the entire climb.

Also note that you do not remove this PCP and use it as part of your hauling system, you need a separate PCP for that. (Yes, this sport is expensive . . .)

The rig looks like this:

Haul rope through Micro Traxion (make sure it’s threaded the right way, duh)

Micro Traxion to locking carabiner

Locking carabiner to top of swivel

Bottom of swivel to locking carabiner

Locking carabiner to haul bag(s)

Here’s a close up or one way to rig it. Note the haul line is clipped above the swivel with a locker as a backup to the Traxion. Docking cord is attached to the long haul bag strap with a quicklink.

No, the teeth on the pulley do not damage the rope. That was my first reaction, isn’t the rope going to get shredded? But nope, it does not. (You ARE using a burly haul rope with a stout sheath, right?)

About the only downside to this system is that you’re adding one more bit of gear that costs about $100. But the upsides can be significant.

Here's a fancier way to set it up, from big wall expert Skot’s Wall Gear.

Here, Skot is using a pair of rappel rings (gold) along with a combination swivel and locking carabiner (appears to be the Director Swivel Boss from DMM). This makes a more compact set up, with zero chance cross loading the rings. Sweeeeet!

PHOTO: @SKOTFROMTHEDOCK, HTTPS://WWW.INSTAGRAM.COM/P/C2NMW-BY0-3/

The far end haul

Having a Traxion on the load also lets you set up what’s called a “far end haul”, which at first seems like some sort of sorcery. The far end haul system allows you to lift your load with a theoretical 2:1 mechanical advantage (MA) by pulling on the “far end” of the rope, rather than from the primary anchor. Here's a detailed article on how to set it up, along with some how-to videos.

But, even if you’re not soloing, it has a few advantages.

You never again need to futz with the old school “water bottle knot protector” that slides up and down the haul line and gets in your way. If you don't have a knot, you don't need a knot protector, right?

You can pull all the extra haul line through the Traxion before you release the bags from their docking cords, and use the extra haul rope to lower out the bags. (Remember to tie that back up knot after you pull all the extra rope through the Traxion; it’s easy to forget this,)

You never have a loaded/welded haul rope knot to untie.

The far end haul can minimize rope abrasion, because the haul rope doesn’t move.

If you have to haul from a point or over a ledge with a LOT of rope friction, you can instead far end haul and have zero friction.

You can easily move the bags around at the anchor; more below.

Simply by redirecting the tail end of the haul rope through a higher anchor point, you can generate a 2:1 mechanical advantage to unweight the bags. This lets you do various shenanigans like transferring the docking cord from one part of the anchor to another. And I can tell ya, if you’re a beginning wall climber, you are just about guaranteed to have some flavor of anchor fustercluck that will require this, ask me how I know this!

If you didn’t have this set up, unweighting the bags once they are settled on the anchor is probably going to be a significant pig wrestle. You want to avoid pig wrestling whenever possible.

Here’s a video by wall ace Mark Hudon who shows exactly how to do this. Rather ingenious, no?

How to (and how not to) rack pickets

You want pickets clipped vertically to your gear loops or pack straps, not slung around your neck. Here’s how to rack pickets right.

What beginning snow climber has not cursed the clanking cowbells and the strangle, tangle and dangle of pickets, hanging from ill-placed runners around your neck and shoulder, threatening to trip you up at each step!

Here’s a better way to rack pickets. Carry 6 pickets like this, with them more or less out of the way yet still easily accessible. (Think of this method as the least of all evils. Pickets are still a drag to carry, no matter how you do it, but this way sucks the least.)

If you have very firm snow, you might be able to use a “top clipped” picket. In that case, girth hitch a single length (2 foot / 60 cm) runner through the top picket hole. Clip a carabiner to the runner, then clip this carabiner to the third hole from the top of the picket.

If you’re clipping the middle picket hole, you're probably going to need a double length (4 feet / 120 cm) runner. Girth hitch this long sling through the middle hole . . .

Then wrap the sling around the picket until there's a few inches left, and clip the carabiner to the 3rd hole from an end.

Then, clip the carabiner to your gear loop (harness or on your pack waist belt). By clipping the third hole, the picket rides high enough to (mostly) not trip you, and stays oriented vertically.

Another option: clip it to your backpack strap.

This works well for the leader and for the second / gear cleaner.

Rack the pickets (to begin with) on the opposite side of where your ice axe is generally held. For example, if you're heading more or less straight up or traversing left, and you're right handed, rack the pickets on your left side gear loop so they don't interfere with your axe.

And, a related tip on who the cleaner should be. Often the slowest or least experienced person can end up in the back of a running belay, and guess what, that person becomes the cleaner. It's usually better to put a less experienced team member in the middle of the team, and have someone more skilled doing the cleaning at the caboose end of the rope.

Also, it’s helpful if the caboose person is taller; the pickets will ride higher and be less of a tripping hazard.

Here’s a few more tips on the running belay.

Finally, it’s fine to girth hitch the runner through the picket hole. That dyneema sling is rated to 22 kN, weakening it by half with the girth hitch means it's still good for about 11 kN, which is way more force than you're ever going to put on a snow anchor. (But hey, if that's not your thing, feel free to clip the sling to the picket with a carabiner.)

Finally, how NOT to rack pickets: don’t put the slings around your neck and let the pickets strangle, tangle and dangle, like this guy.

Use waterproof paper for maps

You probably don't need to use this for every trip, but for outdoor adventures in extreme wet or demanding environments, waterproof paper is just the ticket.

If you’re printing maps yourself (like you should be with great free software like Caltopo), you know the importance of protecting them from the weather. Most of the time, if you print maps on a color laser printer and keep them in a 1 gallon Ziploc freezer bag, that's going to be good enough.

Besides maps, another excellent thing to print on waterproof paper is a SOAP note for your first aid kit.

But in in challenging, wet conditions, you may want to take some extra steps for durability. That's when you might want to consider waterproof paper.

In addition to weatherproofing, printing your maps on stout paper like this or putting them in a plastic bag makes them much more durable. You can fold them multiple times and mash them up in your pocket with little worry they're going to turn into confetti.

“Rite in the Rain” paper, is a fine choice and has been around forever. The one downside is it can tear. It costs about $18 for 50 sheets, or about $0.36 a sheet. If you want to experiment with waterproof paper, this is a low-cost option to get started.

image: AMAzon.com

The next step up in waterproof paper is a type which is actually a sort of plastic, that takes color laser printing beautifully, basically tear proof, and complete waterproof.

How tearproof and waterproof? Watch the first 45 seconds of ths video to get an idea.

The downside of this paper is that it’s expensive (about $40 for 50 sheets, or $.80 per sheet.) But, if you only use it for maps where you really need the extra durability, such as maybe for canyoneering, ski touring in a storm, sea kayaking, or a longer mountaineering trip when you really need your map to last, it could be well worth it.

There are a few different flavors on Amazon. I have a box of the “iGage” paper. When I want to print maps, I make them in Caltopo, save them as a PDF file, put them on a USB drive, take that to the local FedEx store, put a few sheets of my waterproof paper in the top of tray #1, and print my maps as normal.

Disclaimer, this paper is made of a kind of plastic, and it's conceivable that it could jam or melt or do something weird in certain kinds of laser printers. If you do this at FedEx store, you may want to ask an employee if it's OK to use. Personally I've done it many times and never had a problem, your mileage may vary.

image: AMAzon.com

Ascender mod - quicklink in the small hole

Do you have an ascender with a pretty much useless little hole in the bottom? Yeah, so did I until I did this simple modification. Add a 5mm quicklink so you have a second carabiner attachment point, perfect for clipping your ladders.

Many styles of ascenders (the newer Petzl models being an exception) have two holes near the bottom. One is a big one that can fit a carabiner (or two), and the other is a small one that can’t usually fit a carabiner. This small hole can be used to tie a permanent tether from cord so you can’t drop your ascender, something more common on expedition-style climbing with a lot of fixed ropes. (Screen grab below from video about K2.)

Logical question: Why don’t ascenders have a slightly larger second hole so you COULD fit a small carabiner in it? I dunno! If anyone has the answer, please tell me.

image credit: youtube.com/watch?v=Ou3m2Ic4gFE

If you're a big wall climbing instead of on an expedition, here’s an easy enhancement you can do to make this little hole more helpful: add a small quicklink. This makes a handy second point of connection for a carabiner.

I use a Kong 4mm stainless steel link. Cost was about $6. These look pretty darn small, and are not rated or certified by any official CE of UIAA, but apparently the major access breaking load is 1400 kg, which is #SuperGoodEnough. These are a hard to find. I got mine at HowNOT2.store.

A 5 mm stainless link works fine as well. It is of course slightly bigger, and takes a greater variety of carabiner shapes. It also might inspire a little more confidence, so feel free to use 5 mm if you like =^)

Crank it down with pliers and add some Loctite thread locker if you have it.

For ascending and cleaning an aid pitch: use the large hole to clip your tether with a locking carabiner, and the quicklink to clip your ladder with a non-locking carabiner.

Of course, there are some other options to attach your tether carabiner.

Newer Petzl ascenders have one large hole in the bottom instead of one large and one small. This lets you clip both your tether carabiner and your ladder carabiner into the same hole.

You could also clip your ladder carabiner to your tether locker, but I find having them separated with a quick link is cleaner and less prone to twisting and other weirdness.

The foundation of aid climbing is having simple, safe, and easily repeatable systems that you don't have to think about too much. This is one small way to do that. Every time you are getting rigged to clean a pitch, you know exactly where your tether and your ladders get clipped.

Or, if you use a Grigri for an ascending system, you can put a pulley or a carabiner on this quicklink to give yourself a downward pull and a little mechanical advantage when you’re ascending.

Here's the set up for for seconding / cleaning an aid pitch. Tether and locker to big hole, ladder and non locker to quicklink. Simple, clean, easy to check.

This is one of several ways to do it; give it a try and see if it works for you.

Add a release loop to your Fifi hook

Ever wonder what that hole is for in the top of your fifi hook? You're not the first one. Tie a short loop of cord in there to let you easily remove your hook off of pretty much anything.

The fifi hook, a near indispensable tool for big wall climbers to take a short rest, (emphasize short) often has a hole up near the top. (Use of the traditional fifi hook, as shown here, has decreased a bit in recent years, due to the popularity of the adjustable fifi, but this older style still has a place.)

This hole is for you to attach a short loop of cord. If the fifi is loaded, you can grab this cord, pull down on it, and it will lever the hook off whatever it's hanging on. (Sometimes this little “pop” can happen quickly, so be ready for it.) This can be quite handy in certain situations.

I'm using parachute cord tied with a double fisherman's. The orange webbing loop is fairly short, and I have a girl attached to my upper tie in point, that's my preference. Different links and connection options work for different people, try a few methods and see what's best for you.

"Riding the Pig" - rapping with your haul bag

There is a right (and definitely a wrong) way to rappel with a heavy haul bag. Also, learn some specialized crafty rappel tricks if you have a traverse or overhang.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

Descending with your haul bags is the sort of opposite of hauling them, but many of the same principles apply. Here are a few words on hauling, from the excellent big wall climbing book, “Higher Education”, by Andy Kirkpatrick (Buy it here):

“Hauling is potentially one of the most dangerous aspects of big wall climbing. This translates to ultra-caution in all parts of your hauling system and interaction with bags, haul lines, docking cords, and pulleys. If you rush and make a mistake, drop a load or have it shift where it's not wanted, you could easily kill someone or yourself. I try and teach climbers to view their bags as dangerous creatures, like a great white shark, rhino, or raptor that is in their charge. The ability to keep them calm and under your control comes down to paranoia, foresight, and heavy respect for the damage they can do.”

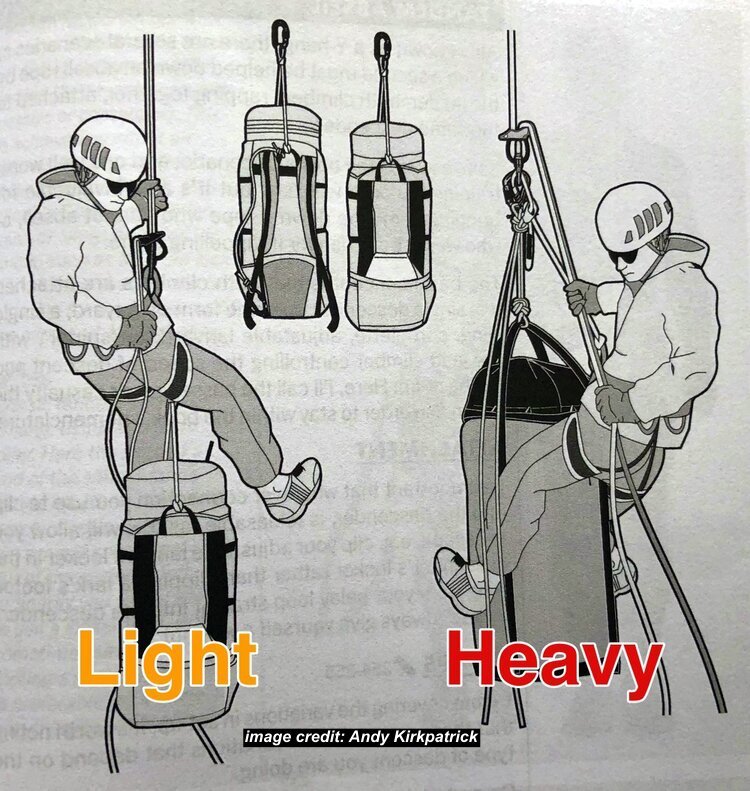

Left: Light to moderate pack or haul bag, hanging from the belay loop. Right: Seriously heavy haul bag, hanging from master rappel carabiner (and definitely not hanging from you!)

Learning to safely rappel with a moderate to heavy haul bag (or pack) is an important big wall skill. You may use it if you have to retreat, and you may do it as part of the normal descent, such as the East Ledges of El Capitan.

With a light to moderately heavy pack or bag, you can get away with clipping it to your belay loop. (In terms of weight, that's roughly the amount you can haul up with one arm.)

However, when you're dealing with a larger load, you do NOT want to attach it directly to yourself in any way. This is much harder to control and much less comfortable; yes, I’m talking sensitive groin area anatomy here!

For a heavy bag, you essentially put the bag on rappel, and then attach yourself somewhere to that system. This puts the weight of the pig on the rappel carabiner, and not on you.

(This is similar to a rescue style “spider” rappel, when you might have to rap with an injured partner.)

Here's a story that provides a great example of why you do NOT want to have your haul bag attached directly to you.

“Two climbers attempting the West Face of Leaning Tower in June decided to descend after arriving at Ahwahnee Ledge (the top of the fourth pitch), due to excessive heat and sun. While rappelling the very overhanging first pitch with the haulbag, Climber A rappelled over a small roof and got too far away from the wall to reach the ledge at the bottom of the pitch, despite clipping some directionals during his descent. With no way to anchor the haul bag, he could not detach it from the ropes nor reascend the ropes to reach the ramp.”

Let's have a closer look at one method in the photo below. There are lots of different ways you could set this up, but this photo shows the main concepts. Some elements are removed for clarity.

Grigri and dedicated HMS carabiner. This is a good place for a triple action or Magnetron carabiner, you absolutely do not want that puppy coming open. There are pros and cons to using a Grigri, more on that below.

ATC works also. You can also rappel on a tube style device with one or two strands of rope. This can work better on old / crusty / large diameter ropes. If you do this, an autoblock backup hitch is mandatory.

Adjustable daisy chain (purple). Used to attach and release the haul bag at anchors. Having an additional longer docking cord could be a fine idea to back up this daisy. Whatever system you use, it must to be releasable under load.

Haul bag master HMS carabiner (gold). Here there's only one bag, but more bags and gear could be attached to this single point.

Adjustable daisy chain (green) and locking carabiner (blue). This is your primary connection to the system. The daisy is attached to your harness and clipped to the Grigri carabiner (#1) with the blue locker; this lets you easily separate yourself from the haulbags if you need to. Note that this connection is very short, so you can reach the Grigri handle. (If you're tall, you can lengthen the connection. If you're short, you could skip the daisy entirely and clip a carabiner from your harness directly to the rappel carabiner.) Not shown, some kind of additional tether for attaching yourself to anchors as you reach them. You can use this additional tether as a backup to the green one after you leave the anchor. (This adjustable daisy is optional, but very handy to fine-tune the length of your connection. If you don't have one, try a locking quick draw or something similar.)

Notes:

As with all critical climbing skills, practice this in advance in a controlled environment before you ever have to do it for real. Small variations in the system can have a big difference in comfort and function.

Wear gloves.

Descending with a Grigri (or similar device) can work well. However, be sure and practice this. Sometimes large loads on a Grigri can be difficult to control, plus your hand can get tired from constantly holding the handle open.

With a standard tube style rappel device, gravity does the work and the rap is generally smoother. If you use a tube device, use a third hand auto block below it as a backup.

Keep any slings connecting you and the haul bag to the master carabiner fairly short. Keeping the slings short means you can easily reach your rappel device. This is of course mandatory if you use a Grigri, slightly less important if you don't. A 60 cm / single length runner works well. Feel free to double up the slings for redundancy if that makes you comfortable.

You need to have a way to dock the haul bags at each anchor. With a heavy bag, this needs to be releasable under load. Hopefully you've been using docking cords on your way up, so you can continue to use them on the way down. Learn more about docking cords here. You can also (as in the photo) use an adjustable daisy chain, such as a Yates.

If you have a lighter bag and don't need a docking cord, have a 60 cm sling with a locking carabiner attached to the bag to secure the bag to anchors.

Depending on your rappel device, you may want some extra friction. To increase friction, clip an additional belay device on your belay loop, and put the brake strands of the rope through that. You can also put two identical carabiners on the master point, and clip the rappel device through both of those.

In a two person team, the haul bags usually come down with the second person.

Have both you and your partner take a close look at your rigging before you start heading down. Keep things as simple and streamlined as possible. Haul bags have been dropped and people have been hurt from doing this incorrectly, so sure and double check your systems.

Begin heading down. Have the bag between your legs so you can kick off the rock as needed and guide it around obstacles. If you have things set up correctly, this should be a pretty relaxed and straightforward process. If you find yourself fighting the pig or straining with your brake hand to hold the extra weight, you're doing something wrong.

Pig riding is relatively easy if your rappel goes straight down. If it starts to traverse, is overhanging, or both, things get more complicated. Check out this article on negotiating over hanging or traversing rappels.

Finally, here's a great video from the always amusing and informative Ryan Jenks, from HowNot2.com, showing different ways to rappel with your haul bag. Yes, it's long, over an hour, but lots of good stuff if you have the time.

Big wall bucket - 5 gallons of stout storage

On your next vertical camping trip, use a “big wall bucket” with a Gamma lid to keep delicate items from getting crushed, and to keep day use gear close at hand.

Want to have delicate items on your next vertical camping trip remain unsquished from the grinding wear and tear of the big wall haulbag? How about keeping your phone, camera, water, snacks, rain shell, fleece jacket and sunscreen close at hand during the day? You should not be diving into your hall bag in the middle of the day, pull out what you need in the morning.

The answer: the big wall bucket.

What you need:

5 gallon plastic bucket, paint store or big box hardware store (or maybe free from a doughnut shop or big supermarket bakery)

Gamma lid. This is a clever contraption that lets you install a screw-on lid to a 3 or 5 gallon standard bucket. This is a WAY better option than fighting a tight paint bucket lid with beat up wall hands!

A few feet of 3 mm cord or other really strong cord, like bank line

About 5 feet of tubular webbing, diameter not really important

Drill and bits (or knife with sharp tip)

This is a gamma lid:

Install the gamma lid “ring” onto the top of your bucket. I found about the easiest way to do this is to position the ring part of the lid on the top of your bucket, put a 2 by 4 or piece of scrap wood on the top, and tap the wood a few times with a hammer.

Reinforce the handle with 1 inch webbing. The wire handles on these buckets are fairly strong for around the house, but not stout enough for the rigors of big wall climbing. Back up the handle by drilling a small hole in the side of the bucket near where the handle connects to the bucket, inserting one end of the webbing, tie a stopper overhand knot on the inside, spiral wrap the webbing around the handle, and then repeat the hole and knot program on the other side. Wrap some duct tape around the webbing/wire handle to keep it tidy.

Try to make the holes you drilled as small as possible to make it harder for water to get in. You’ll probably need some needle nose pliers to pull the webbing through the hole, and consider putting a dab of silicone sealant around the webbing hole junction as some additional water protection.

Add a keeper cord to the lid. Everything on the wall needs to keep record so you don't drop it. Take about 3 feet of thin cord, like 3 mm from the climb shop (or bank line) and drill two small holes, about 1 inch apart in the side of the bucket about 2 inches down from the top. Make these holes just a hair larger than the cord in the side of the bucket. Pass the cord through the holes, and tie a bowline knot to secure it. Repeat this near the center of the lid. Now your lid is permanently attached to the bucket and you can’t drop it.

Hang this bucket on a tether cord below your main haul bag. You can pull up on the cord to access the bucket anytime you want during the day. And, anything inside it is guaranteed to be uncrushed and pretty much watertight. Read more on gear tethers here.

Wall buckets have been around for a long time. I first heard about this tip from Climbing magazine, published in 2002. The Gamma lid is a definite improvement.

Note the tied off ends of brown webbing inside the bucket, backing up the wire handle, and the lid keeper cord. Duct tape keeps the webbing and wire handle together.

Ascending - have both tethers the same length

When ascending a rope with jumars, the length of your tethers is critical. Here’s a way to get them set up right every time, and a good reason why you want both of them the same length.

When you’re setting up your tethers and jumars for ascending a rope, getting the correct length for the tethers is critical. If it’s too short you’ll be making short, choppy, and efficient strokes. If it’s too long, you can’t easily reach your upper ascender from the rest position, and you’ll flame out your arms and abs in a few minutes.

(You may want slight variations on this “ideal” length. For lower angled slab pitches, you might want the tether a bit shorter; for steeper pitches, maybe a bit longer. But you do need a starting point.)

Here are a few guidelines for getting the tether length set correctly.

With the tethers girth hitched to your belay loop or tie in points (there are pros and cons to both, see below), pull the daisy tethers up vertically in front of you.

The bottom of the locking carabiner should be just about at the middle of your forehead. (See photo below)

Now, clip the ascender to your fixed rope and put full body weight on it. If you reach straight up, your wrist should be at the top of the ascender. This positioning ensures that you have a gentle bend in your elbow when your hand is grabbing the handle, and you can easily reach the trigger on the cam. Take the time to get this right. (It’s been my experience that most new aid climbers initially make their tether too long.)

Tip - Once you determine the correct connection length, mark this on your tethers. If you have adjustables, add a Sharpie pen mark. If you have traditional sewn pocket daisies, add a loop of 2mm or so cord or stout string (or burly tape like hockey tape) to the correct loop to mark it. By doing this, you set it once, and you can quickly adjust it to the right spot anytime in the future.

Big wall ace Mark Hudon shared a good tip with me. Most people think only your dominant hand tether needs to be the perfect length, and the length of the other one doesn’t really matter.

Mark says: have them both at the same length.

Reason: When ascending, whatever way the route goes, you should lead with that hand. Say that you’re right handed. If the pitch goes pretty much straight up or to the right, you’ll be leading with your right ascender. But, if the pitch leads to the left, you should be leading with your left hand ascender. In that case, the tether length should be the same as the right.

Here’s a photo of the proper set up. See that the bottom of the carabiner is just about at the climber’s forehead? When weighted on the rope, it should settle into the correct position.

So, where to attach the daisies to your harness, the tie in points or the belay loop? Both locations have pros and cons. (The front of your harness is going to be a clustered junk show no matter what you do, so get used to it.) Try both and see what you like. If you want to take a deep dive into this, check out this article.

Tie in points: redundancy, gets you closer to the gear and thus higher in your aiders (if you have an adjustable tether), but can be uncomfortable as it’s squeezing your groin as your tie in points are smushed together, like you just took a fall.

Belay loop: more comfortable, can be redundant if you have a harness with two belay loops, puts you farther from placed gear.