Alpine Tips

Big wall beverage holder

Here's a way to repurpose some gear at your big wall bivy so you’ll never spill that precious can of . . . prune juice.

This tip come from big wall ace Pete Zabrok and his excellent new book “Hooking Up - The Ultimate Big Wall and Aid Climbing Manual”. Highly recommended for aspiring aid climbers!

One of the more vexing questions for big wall climbers is, “Where da heck do I put my beverage?! The last thing you want at your bivy is spilling that precious can of . . . prune juice, but there is a serious lack of flat spots to put it. (An extra chalk bag, of course without chalk, also works well with this.)

Fortunately, resourceful big wallers came up with a crafty solution.

Use CalTopo layers in Google Earth

If you have a Caltopo subscription, you can view all of those cool map layers as overlays in the 3D splendor of Google Earth. Warning - for map geeks only . . .

If you're new to using CalTopo mapping software, watch this tutorial to get started.

Disclaimer: This article is pretty much for map geeks only. Having said that, it’s pretty darn cool and you might well find some uses for it that I can’t imagine. I've been a CalTopo nerd for many years, and I didn’t know about this feature until recently, so I thought I’d share it.

Have a quick look through the photos below, and if it looks interesting, give it a whirl.

Here's how it works: If you have a paid subscription to CalTopo (and you should, it’s well worth it) one benefit is access to what are called “Super Overlays.”

What the heck is a Super Overlay? It lets you use pretty much all of the CalTopo map layers in the 3-D splendor of Google Earth!

(The helpful tips on this CalTopo blog/help page cover it pretty well.)

Login to your CalTopo account. Click your email address in the upper left corner of the CalTopo screen, then click the “Account” tab. You should see a screen that looks something like the screen grab below.

See that arrow and the red box at the bottom after the “KML”? That’s the “super overlay” KML file you want.

Right click that link to download the super overlay KML file to your hard drive.

Then, open it in Google Earth. (Tech note: “KML” is a type of a geographic data file that plays nicely with Google Earth.)

I blocked out part of the link because the CalTopo team does not want people to share it. You need to pay for a subscription and get it yourself.

For this example, we’re looking at the Mt. Whitney area in the California Sierra.

Once you open the super overlay KML file in Google Earth, you should see a menu on the left that looks something like the red box in the screen grab below.

If you check any of these boxes, that map information from CalTopo will overlay onto Google Earth.

I suggest checking ONLY one layer at a time, and zooming into a fairly small area so it redraws fairly quickly, depending on your computer speed and web connection speed.

Some layers are more helpful and interesting than others. Try a few and see what you think. Some examples are below. (Note, these layers look MUCH more impressive on a full width desktop computer screen than the screen grabs below.)

Here’s the 20 meter contour layer overlaid onto Google Earth.

Here’s the custom CalTopo layer “MapBuilder Topo” layer overlaid onto Google Earth, with trails, shaded relief, streams, wilderness boundary, and more.

Another interesting overlay is slope angle shading. These are indicated by the “Fixed” and the “Gradient” boxes. Here's the Emmons glacier route on Mt. Rainier. You can see how the route pretty much takes the path of least resistance/lowest angle slopes.

Hopefully you get the idea. Zoom in to an area you’re familiar with, load up a few CalTopo layers in Google Earth, and have fun playing in the sandbox!

Pocket Fresnel lens for the small print

Carrying a credit card sized Fresnel magnifying lens can really help with reading the small print on a map or your phone. Good news, they weigh pretty much nothing, have 3X magnifying power, and cost about $1 each.

So, the way I heard the story . . . Several older and experienced hikers were hiking in the Columbia River Gorge. As light was fading, they needed to make a route choice at a trail junction. They pulled out their map . . . and couldn’t read it because no one had reading glasses! They didn’t know where to go, and decided to stay put for the night. (That was probably the best choice, and luckily they had the gear to do so in reasonable comfort.) The next morning, when there was enough light to read their map, they walked out unassisted.

For more “well seasoned” climbers, reading the small print on a map or phone screen can be tricky. But who wants to bring reading glasses on a hike or climb?

A lightweight, inexpensive, and functional solution is a pocket Fresnel (pronounced fruh-nel) magnifying lens.

image: https://www.amazon.com/Outus-Plastic-Reading-Magnifier-Firestarter/dp/B06W5FCS4Q/

These little puppies are simply thin, flexible, plastic magnifying glasses. About the size of a credit card, they are dirt cheap, magnify to about 3x power, and really help to read that 8 point font. (The image clarity is not as good as what you’d get with a lens actually made of glass, but it’s probably good enough to read your map and make the correct trail choice.)

If you want to show off your bushcraft skills, they can apparently be used in a pinch to even start a fire, provided you have steady hands, perfect tinder, and bright sunshine. (Disclaimer, I have never done this, your mileage may vary, and YouTube is your friend.)

You can get a multi-pack of pocket magnifier lenses online for something like $1 each. So, buy a bunch, keep them scattered around your gear bags, and give ‘em away to your friends. Search Google for “pocket Fresnel lens”.

Science geek note: the Fresnel lens was invented by a French physicist in the 1800s, and was originally used in lighthouses to concentrate the light beam. Several excellent examples can be seen at historic lighthouses, including several in Oregon. When seen full size in a lighthouse, they are quite amazing!

Fresnel lens in Cape Mendocino lighthouse, California. Image: Wikipedia

Decluster your anchor: Put lap coils on a sling

At a hanging belay or small stance, keeping your rope tidy and giving a smooth belay to the leader is a lot easier if you move the coiled rope away from your tie in connection and attach it to some part of the anchor.

This tip is from AMGA Certified Rock Guide Cody Bradford. While sadly Cody is no longer with us, his Instagram continues to stay up and is a great source of tips like this, check it out.

On a multi pitch climb, rope management is a key skill to staying cluster free and moving efficiently. The basic question is, ledge, or no ledge?

If you have any sort of a ledge, you can often (neatly) pile the rope at your feet.

If you're at a small stance or full hanging belay, the typical approach is to make lap coils over your tie in connection.

However, these lap coils can be cumbersome, especially when belaying a leader.

Below is the standard approach of the rope draped over your tie in connection. Do you think this might be awkward when you try to belay your leader from your belay loop? (Answer, yes.)

image: Cody Bradford, https://www.instagram.com/p/BsZCqrpBXpu/

Solution: hang the coils from a sling on the anchor. The rope stays tidy AND out of your way. Much easier to belay your leader on the next pitch.

image: Cody Bradford, https://www.instagram.com/p/BsZCqrpBXpu/

Here's a short video by Cody Bradford that demonstrates this simple and effective technique. (He's doing it on ice, but it works fine for rock climbing as well.)

Bounce test to learn gear placement

Learning how to place rock gear, and want a little assurance that your pro might be able to take some real force? You can learn a lot without getting more than a foot or two off the ground by bounce testing at your local crag.

Starting out learning to place trad gear and build anchors? It looks like a decent placement, but is it really going to hold? A great way to build confidence in your gear placements (as well as get lots of practice using your nut tool) is take a page from big wall climbing: bounce test your gear.

While a bounce test is probably going to put between 2 and 3 kN on your piece, quite a bit less than the maximum force of about 6 to 7 kN it might see in a big actual fall, it can definitely boost your confidence that you’re placing your gear correctly.

The image below is a screen grab from a video from our friends at HowNot2.com, showing the actual force generated during a static sling bounce test.

image: HowNot2.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gq3_DfyHg1A&t=781s

You may hear advice of “go aid climbing” to learn how to place gear. Not a bad idea, but it does require lots of extra stuff like a rope, a patient belay partner, and aiders, fifi hook, daisychains, and probably ascenders. You actually don't need any of that; you can bounce test and get the same learning pretty much standing on the ground.

What you need: base of a cliff area with lots of various sized cracks to place gear, a decent trad rack (can maybe borrow from a good friend), a cleaning tool. Optional but suggested: a hammer and eye protection/safety glasses.

How to do it: At the crag, make a placement that you can reach from the ground, and clip a runner or two to the gear. Extend runners as needed so when you step in it, it’s about knee level. (You want to keep your feet close to the ground when you do this because if the piece pops out, that means you won't take much of a fall.)

Give it a decent tug.

Did it move? Does the rock on either side look solid? Good.

Now, carefully step into the runner, and give it a little bodyweight. (If the placement is near or above your head, you might want to cover the gear with your hand. If the gear pops, it’s going to zing out somewhere in the neighborhood of your eye - remember those suggested safety glasses?) Did the gear move it all? If not, sweet, probably a good placement.

Now, start jumping on the sling with increasing enthusiasm. Did the gear shift a little bit and then hold? Might be OK, but probably could be improved. Did it sprout wings, fly out of the rock and almost hit you in the eye when you jumped on it? Definitely needs more work.

And, like I said, be sure and bring a cleaning tool and perhaps a hammer, or at least a baseball sized rock or big hex, so you can (gently) beat on those welded stoppers to be sure you take everything home. (You might not want to bounce test a Tricam, which are notorious for being hard to clean after they’ve been weighted.)

It’s one thing to put in a piece of gear, look at it, and hope it’s well placed. It’s quite another to jump on it with enthusiasm and know with more certainty. If you have a more knowledgeable friend to work with on this, they can critique your placements.

Here's a nice short video that shows the basic technique. (Note that here it's demonstrated using standard big wall equipment such as aid ladders and daisy chains, but pretty much the same procedure can be done very close to the ground with a few slings.)

And finally, here's a video from our friends at HowNot2.com showing the actual force is generated from bounce testing. (it's a long video, start at 13:00 to see the testing part.)

Snow picket - vertical or buried deadman?

A vertical picket is fast to place, but the strength depends on the firmness of the snow. Here’s a quick rule of thumb to determine if the snow will hold a vertical picket, or if you need to take more time and make a T slot (deadman) anchor.

When placing a snow picket, a key decision is whether you can place it vertically (preferably leaning back about 25° from the direction of pull for optimum strength) or if you need to bury it as a deadman, a.k.a. T-slot.

If you're using it for crevasse rescue, where the anchor has to be unquestionably strong, a single T-slot or possibly a T-slot equalized with a vertical picket is usually the best choice.

In firm summer snow in ideal conditions, you might get away with a vertical placement, which is good because it's faster.

If you make a vertical placement, you get a much stronger anchor if you clip the picket in the middle instead of the top. From IFMGA certified guide Mark Smiley, on his Instagram, he writes:

“ . . . if the snow is soft enough to push one gloved finger into it, a top clipped picket will likely fail under 500 pounds (~2 kN) Yikes! A deadman style picket placed 60cm down = strength of midclip vertical pickets = ~1500 pounds (6.7 kN)”

(Side note: One of the best studies on snow anchors is from the 2010 International Snow Science Workshop, from a paper called “Snow anchors for Belaying and Rescue”, by Don Bogie (New Zealand) and Art Fortini, (USA). You can see it here.)

But if you're unsure of the firmness of the snow, here’s a good rule of thumb, also courtesy of Mark Smiley:

“Typically if it takes 10+ solid hammer strikes to drive the picket to the deepest hole (top of the picket), then I have confidence the snow is firm enough. If less than 10 strikes, I will switch to building a T-slot anchor...which takes longer to build but it’s stronger.”

Mark’s tip is in the comment section of this excellent Youtube video from Outdoor Research, “How to Build a Snow Anchor.”

Look at stream flow patterns to see elevation change

From a quick glance at stream patterns on a map, can you get a sense of where the high and the low elevations are? It's a helpful skill you can quickly learn.

Stream flow patterns on a topographic map can show you at a glance the higher elevations and lower elevations.

This map section below (from the US Geological Survey 7.5 minute map series) is in the Oregon coast range. Just by looking at the stream flow patterns (and without looking at the printed elevations (which are pretty darn hard to see anyway) can you tell where is the high ground and the low ground? And, for extra credit, what’s the lowest point on the map?

Here are a few ways to tell general map elevation from stream flow patterns.

A good starting assumption: water flows downhill. =^)

Smaller streams flow together to become larger ones.

When streams come together, they usually form a “V” shape. The two arms of the “V” point upstream, to higher ground. The tip of the “V” points downstream, to lower elevation terrain.

The origin of a stream on a map is called the “headwaters”. The stream always flows downhill from that point.

Contour lines always bend to point uphill when they cross a gully or drainage.

Let's look at a few examples.

When streams come together, they usually form a “V” shape. The two arms of the “V” point upstream, to higher ground. The tip of the “V” points downstream, to lower elevation terrain.

The origin of a stream on a map is called the headwaters. The stream always flows downhill from that point.

Contour lines always bend to point uphill when they cross a gully or drainage. (Look at the index contours, printed in bold every 5th contour line, they’re easier to see. Shown in red line below.)

So, when we put all that together, we see that Jordan Creek in the center is flowing from right to left (or east to west, if you prefer), being fed by various other creeks flowing from higher elevations.

Try this yourself. Go to Caltopo.com, zoom into a familiar area that has some streams, and see how all of these factors come into play.

And finally, because we know Jordan Creek is flowing from right to left (and because water flows downhill) the lowest point on the map is the one indicated below.

And as always, stream flow patterns, gullies, ridges and other landscape features are much easier to see when you use a map that has shaded relief. This is easily done in Caltopo for free. The map below has about 30% relief shading. Here’s a whole article on shaded relief, check it out!

If you are new to using Caltopo, it’s a wonderful mapping tool. I made a tutorial video on how to get started using it, you can watch that here.

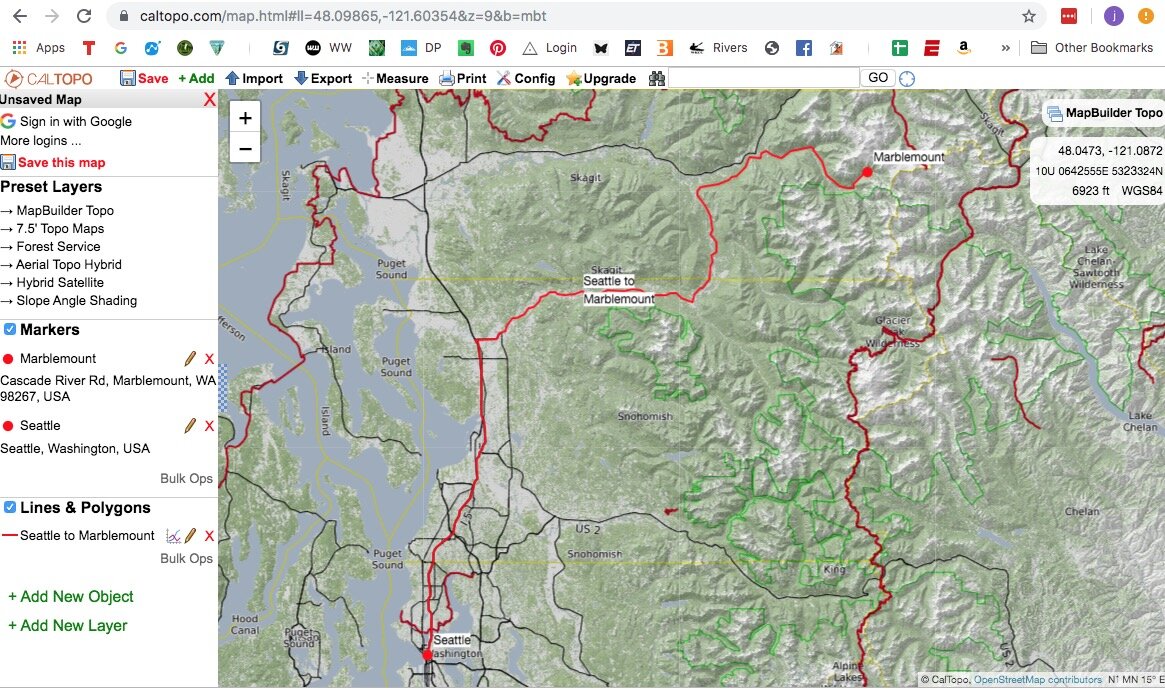

CalTopo pro tip - split tracks, add colors and direction

On loop routes, it’s handy to use different line colors and/or styles to easily see the ascent and descent. This can be especially helpful when sharing your route with others who may not be familiar with it. CalTopo can do this easily with the “Split Here” feature.

(If you want to learn the basics of using CalTopo, start with this tutorial video.)

A more advanced tip in CalTopo (the best backcountry mapping software) is to “split” a track and give different legs a unique color and/or line style. Doing this shows at a glance the way up and the way down, and is especially helpful if you have a loop route on a climb or hike.

If the map is just for you, and you know the route, you probably don't need to do this. But if you want to share your route with others, doing this takes just a minute or two and makes the map much more usable for those who are not familiar with the route.

Here’s an example of the Mountaineers Route on Mt. Whitney in the California Sierra. What you’re seeing is a GPX track of the route (traced over to remove squiggles) downloaded from Peakbagger.com, which is a great source for finding GPX track files for climbing routes. We cover how to do that in this article.

Here's the entire route. The ascent route breaks off from the main climber’s trail a mile or so after the parking area, and proceeds counterclockwise. But, If you’re not familiar with the route, you wouldn’t know what’s the ascent and what’s the descent just by looking at this map.

So, let’s split the GPX track into two parts, the “up” part and the “down” part.

Zoom in close to the summit area, mouse over the line until it turns bold, select “Modify” > “Split Here”.

This splits the one line into two. The line still looks the same on the map, but if you look on the left side of your screen, now you should see two lines with the same name.

Now, let’s change the color. Click the “pencil” (aka Edit) icon next to the name under “Lines & Polygons” on the left side of your screen. Click the small red square in the edit box to choose a color. For this example, we’ll choose green for the ascent.

And, to clearly show the direction of travel, let’s change the line style to one with some directional arrows. To do this, click the “Pencil” edit icon again, and click the horizontal line that comes after “Style” in the edit dialog box.

Repeat this with the second line, choosing a blue line color and the same directional arrow.

Now, that’s an improvement! Someone seeing this map for the first time can immediately determine the ascent and descent. If you’re making a map for any kind of public sharing, even if it’s with some other teammates on your trip, taking an extra minute or so to do this makes your map more legible for everyone.

And finally, below is a screen grab of the PDF file of the map made from CalTopo, which prints nicely on 8.5” by 11” paper at 1:25,000 scale. Print this to use on your climb, and save it as a PDF on your phone as a backup. (The base map is USFS 2013, with about 20% shaded relief.)

Redirect the Grigri brake strand for extra friction

If you're using a Grigri or similar device on a top rope belay, and you have a heavy partner, small diameter, and/or wet/icy rope, sometimes you need additional friction. Here’s an easy way to do that - redirect the brake strand through a second carabiner.

When top rope belaying with a Grigri or similar auto locking belay device, you may find you need extra friction when lowering. This could be due to lowering a heavy partner, skinny rope, slippery rope sheath, wet/icy rope, cold hands, gloves, or some combination of the above.

One crafty way to do this is to redirect the brake strand through a second locking carabiner clipped to your belay loop.

You can use a normal locking carabiner to do this, or the more specialized (and expensive, and strange looking) Petzl Freino carabiner, which has a secondary “braking spur” designed specifically for rope redirect and extra friction when belaying or rappelling a single rope strand.

IMAGE: HTTPS://WWW.REI.COM/MEDIA/PRODUCT/716219

Like with all lowering techniques, the effectiveness of this depends greatly on the variables mentioned above: rope diameter, how slippery the sheath is, if the rope is wet / icy, weight of your partner, etc. Practice in a controlled environment before you try it in the real world.

Karsten posted two nice photos on his Instagram, which pretty much sums it up.

Method 1 - SOME extra friction - brake strand redirected through the gold locking carabiner.

photo: instagram.com/karstendelap/

Method 2 - a LOT of extra friction, with the brake strand redirected through the locking carabiner AND passed back over the Grigri.

photo: instagram.com/karstendelap/

New from CalTopo - high resolution slope angle shading

CalTopo, the best backcountry mapping software, just got even better. The slope angle shading is now at an even higher resolution, improving wilderness trip planning for much of the United States. See some examples here.

If you’re new to CalTopo and want to learn the basics, start with this tutorial video.

Note: this type of slope shading is made with an elevation model that may not show all relevant features and potentially hazardous avalanche slopes. It can be a useful tool for macro level trip planning, but is not accurate enough to completely assess potential avalanche hazard across all types of terrain.

Slope angle shading is a very cool feature of CalTopo, the best backcountry mapping software. It’s handy for lots of different reasons, and we cover them in detail in this article.

Canyoneers or photographers, looking for seldom-seen waterfalls?

Backcountry skiers, looking for a low angle ascent and a slightly steeper downhill?

Winter travellers looking to (hopefully) avoid avalanche slopes?

Cross country hikers or mountaineers, looking for the path of least resistance?

Slope angle shading can help in all of these situations. Now, the digital mapping data that underlie the slope model is improved, and the resulting shading is much higher resolution.

Here’s a comparison of the old and new slope angle shading, with the Disappointment Cleaver route (red line) on Mount Rainier. The top image is the older style shading, the bottom image is the newer one, using the higher resolution LIDAR data.

Pretty cool to see how the route picks it’s way up through the path of least resistance. You can use this feature to plan a cross country travel route in CalTopo for a place you've never visited! (Of course, glaciers can change on a daily basis and you should never fully rely on a model like this, but it’s a great start.)

Caveat: This new data set does not cover all of the United States, and is sadly lacking in many parts of the western US, but hopefully that will be improved in the next few years as additional LIDAR data are collected. See the data coverage map below. (Sorry Wyoming, Montana, and Sierra Nevada.) Good news, you are highly unlikely to be caught by an avalanche in Louisiana. =^)

Below is a copy/paste from the CalTopo website, Dec 20 2019.

http://caltopo.com/about/2019/12/20/high-resolution-elevation-data/

“CalTopo first launched the slope angle shading layer 7 years ago, and since then it has become a mainstay tool for backcountry trip planning. Today we're updating the layer to incorporate high-resolution LIDAR data from the USGS's 3DEP program. Where available (see coverage map), this provides significantly higher resolution, even allowing you to identify trails from relief shading. As additional coverage becomes available we will add it to this layer.

While the LIDAR data is very high resolution, it should still not be relied on as a definitive source of truth. Beyond possible errors or accuracy issues with the dataset or our processing of it, the surface angle on top of a snowpack may not match the bare-ground angle underneath. Carefully assess and evaluate any terrain that you are traveling in, and confirm your observations instead of relying solely on maps.

This update is now live on the web! It will be released soon on iOS and Android. Offering online access for free, and offline downloads with a CalTopo subscription. The significant increase in resolution means the offline downloads are larger in size than previous elevation data. Be cautious downloading using mobile data and storing on your phone, storage may go quickly.

As with previous expansions of the slope angle shading layer to Canada and Alaska, the high resolution dataset is not available to third party apps that license CalTopo's pre-rendered layers like Gaia GPS and Backcountry Navigator. You can only access the layer via CalTopo's website and app; we encourage you to download the new app to use this layer in the field.”

“Rock shoe rejuvenator” - rubbing alcohol

There's a quick and easy way to revive your rock shoe rubber - Give it a quick scrub with some rubbing alcohol (and maybe sandpaper.)

Rock climbers love that incredible stickiness from a brand new pair of rock shoes. But when dust, chalk, grime etc. get slowly ground into the rubber, it seems like you never quite get back the “grip-tion” of new shoes.

Well, you can, or at least get pretty close. Wipe down your shoe rubber some rubbing alcohol. Do this outside, as the fumes can be strong. A rag works better than paper towels.

Some gentle buffing with 80 grit sandpaper or a wire brush can help rough up the surface and make your shoes a bit stickier as well. Give it a try before your next hard boulder problem or red point attempt; every little bit of grip helps!

Safety for leader #2 on sport routes

If you’re leading a sport route at your limit, having the first bolt clipped increases your safety by eliminating a ground fall. With this simple rope trick, the first leader can pre-clip the first bolt for the second leader.

Heidi and Hans are out for a day of sport climbing, and they both want to lead all the pitches. They don’t have a stick clip. Heidi, being the stronger climber, feels fine with leading without the first bolt being clipped.

But Hans is leading at his limit. He wants to reduce his risk by having the first bolt clipped, eliminating any chance of a ground fall.

Here’s a simple way to do that, with the one caution that you need to have a bit of extra rope.

Say Heidi leads the route first. She climbs the route, clipping all the bolts, clips the anchor, and calls for a take and lower.

On her way down, she clips a quickdraw to her belay loop and to the rope running through the bolts; this is known in some circles as “tramming”. Doing this keeps her close to the rope and gear, which is especially helpful on traversing and/or overhanging routes.

Note the quickdraw clipped to the climber’s harness and the rope in this nice diagram from Petzl. Perfect tramming technique!

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Recovering-quickdraws-in-an-overhang-while-descending

She calls for a brief take at each bolt and removes all the quickdraws, except the one on the lowest bolt.

When Heidi gets to the lowest quickdraw, she does not clean it, but instead keeps lowering to the ground. Doing this keeps the rope through the lowest quickdraw.

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Recovering-quickdraws-in-an-overhang-while-descending

Heidi unties, but keeps the rope clipped through her quickdraw. Hans pulls the rope. The rope zings through the top anchor and falls to the ground, but now it’s clipped to the first bolt. This gives a “toprope” to the lowest bolt for Hans on his lead, with no chance of a ground fall.

Using this technique can be more helpful in climbing areas that often have hard moves right off the ground, or have first bolts that are especially high, or both. (Smith Rock, I'm looking at you!)

Using this “tramming” method guarantees that the rope end will fall to the ground, every time. If the route is fairly steep, without any ledges, shrubs, or anything else the rope may get hung up on, you can probably skip doing the tramming. Just leave the rope clipped to the first quick draw, have the belayer pull the rope, and the end should fall to the ground and stay clipped to the lowest bolt.

But keep in mind, if you do this, and the end of the rope does not cleanly fall to the ground, you're probably going to have to pull it through that lowest draw, and it won't be clipped anymore, which defeats the whole purpose.

Safety notes:

Caution #1: Doing this requires you have enough extra rope that is twice the distance from the ground to the first bolt. If your route is a real rope stretcher, or the first bolt is really high, this technique might not work.

Caution #2: The belayer should always be tied into the end of the rope, or at the very least have a knot in the end to have a “closed rope system”. This technique takes a bit of extra rope, and you definitely do not want to drop your leader. One more reason to get a 70 meter rope . . .

Remove rope twists with an ATC

Got some serious twists in your rope? Ugh, you need to get ‘em out. Here’s a fast way to do it with an ATC style belay device.

This tip and video come from AMGA Certified Rock Guide Cody Bradford.

While sadly Cody is no longer with us, his Instagram continues to stay up and is a great source of tips like this, check it out.

Did you unwrap a new rope in a hurry? Lowered off an anchor with quicklinks lying flat against the rock? Munter hitch rappel? Or just have some random rope weirdness? Twists (aka pigtails) in your rope can come from a lot of different sources, but no matter how they got there, they’re a hassle and you need to get them out.

Here's a simple and fast way to decluster your spaghetti pile.

Clip a carabiner and a tube style belay device (here the DMM Pivot, my fave) to a bolt, some rock pro, tree branch, whatever, about head high.

Flake the rope onto the ground.

When you get to the tangled part, feed the rope through the belay device and carabiner, and pull the rope through. Give the twisted side of the rope a few shakes and shimmies as needed.

As the rope is forced through the small diameter of the belay device, the twists move to the end of the rope and should work themselves out. If your rope is REALLY messed up, you might need to repeat this.

Pigtails in your robe can be more than a minor annoyance. It’s especially important to remove them when you're pulling a rappel rope. If you don't, the strands can twist together or other weirdness, making your rope very difficult to pull, or maybe even impossible. Check out this description and photo from @aledallo91.

“. . . a crunch created during the recovery of a rope on a broken descent on two anchors that forced me to abandon it, as it was impossible to recover from the intermediate stop. Then I went back up to save my baby. ❤️

This ball was formed by itself in recovering the rope, due to the twisting of the last meters of the same.

Experience that teaches the importance of checking that the rope is always well stretched and free of slots and twists before attempting the retrieve.”

Like most climbing techniques, it’s a better show than a tell. Here’s a short video from Cody showing how it’s done.

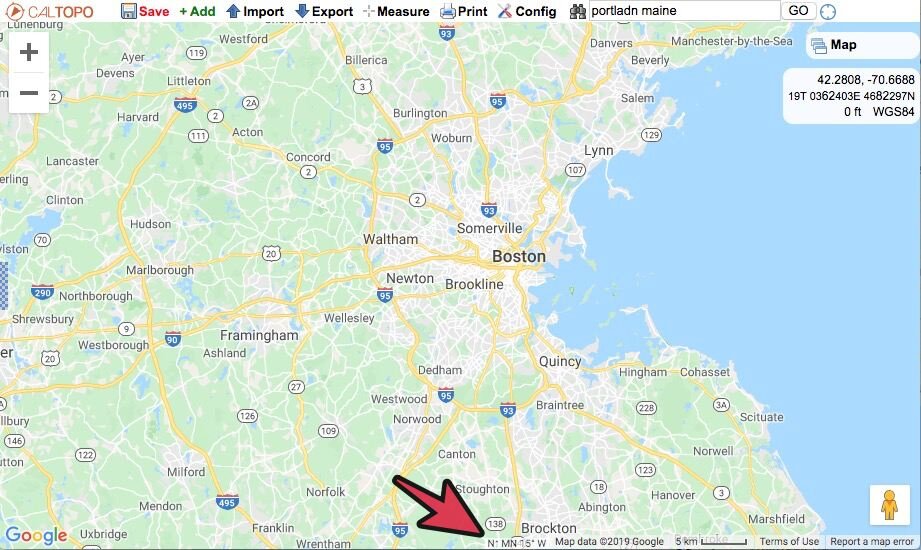

See the correct declination in CalTopo

When using a compass, it's important to know the magnetic declination for your area. Websites like magnetic-declination.com make this easy. You can also see it in CalTopo, right at the bottom of the screen.

(If you want to learn the basics of using CalTopo, start with this tutorial video.)

Magnetic declination is the angular difference between true north (North Pole) , and magnetic north, which is where the red end of the compass needle points. This changes depending on where you are in the world, and it also changes over time. If you’re using an older map, the declination printed in the margin might well be incorrect.

(If you want the full scoop on declination, watch my video here.)

So, whenever you're using a compass, it's important to know the correct declination for your local area. One good way to do this is to check the website magnetic-declination.com, as we cover in this article.

Here's another way. A helpful little feature I just discovered in the best backcountry mapping software, CalTopo, is hiding in plain sight at the bottom of the CalTopo screen - the correct magnetic declination for (I think) the center of your screen.

(I've been a fanatic CalTopo user for many years and never noticed this before today. Who knows how long it's been there and I just never saw it? =^)

Here are a few examples. (Depending on your web browser, it might look slightly different than this; I’m using Chrome on an iMac.)

Declination for Seattle, about 15° east.

Boston? About 15° west declination. (Don't worry, that won't help you in Boston, you're still going to get lost driving there. =^)

How about New Zealand, a country with some pretty extreme compass declination because it's fairly close to the south magnetic pole? 24 degrees east.

Finally: If you print a map in CalTopo, the correct declination is shown in a diagram on the bottom right of the PDF file.

How to transfer GPX files from Google Drive to the GaiaGPS app

Storing your GPX track collection in Google Drive is handy for a lot of reasons, but moving a file from there into Gaia GPS is not very intuitive. Here are two ways to do it. (OK, not a climbing trip directly, but still can be helpful.)

Upfront disclaimer: this is really not much of a climbing tip. It's more of a computer geek tip, but if you have a collection of GPX track files in Google Drive, you might find it helpful. We’ll get back to our regular climbing tips after this one, I promise.

It's handy to keep a collection of good GPX track files in Google Drive, because you can access them from pretty much anywhere to either use on your phone or share them with your hiking or climbing partners. GPX files are just small text files and hardly take up any room, so when you find one that you think you might have a use for in the future, download it and save it! (Even if it's unlikely that you will go on the trip, you might be able to share it with someone else and help them.) Personally, I have hundreds of GPX tracks on my Google Drive, organized in folders for climbs, hikes, mountain bike rides, road bike rides, ski tours, etc.

However, most people do not find it very intuitive to move the files from Google Drive into a backcountry GPS phone app such as Gaia GPS.

But, like most computer related things, it’s easy once you know how. Here are two ways to do it, one method via a desktop computer, and one method all on your phone. (These instructions are for the iPhone, which is what I have, Android folks probably can do something similar.)

To do this, you’ll need:

a Google account with Google Drive

a folder on Google Drive with some GPX files in it

an account at GaiaGPS.com

the Gaia GPS app loaded to your smartphone.

Method 1 - Desktop / laptop computer

Step 1 - From a desktop / laptop computer, go to Google Drive, navigate to the GPX file you want, right click, download to your computer.

Step 2 - Go to GaiaGPS.com account, click your username or photo in the top right corner, and choose “Upload” from the drop-down menu, screen grab below. Navigate to the GPX file you just downloaded, and select it. (Personally, I do not find this website very intuitive to use, so I thought I’d spell out how to upload a file.)

Step 3 - Open the Gaia GPS phone app. Go to Settings > Account, and toggle the “Sync/Backup” off and back on. Doing this should synchronize all the geo-data in your GaiaGPS.com account, including the track file you just uploaded, with your phone. (The GPX track you just uploaded will probably appear in Saved > Folders on your app.)

Method 2 - Google Drive on your phone to Gaia GPS on your phone

Step 1 - Open the Google Drive app on your phone, navigate to the GPX file you want to use, and tap the “three dots” icon after the file name.

Tap “Open In”. This downloads the file to your phone and gives you an option of several apps in which to open it.

Scroll sideways if needed and select “Copy to Gaia GPS”. This should launch the app and import the file. To see your file, tap Saved > Folders.

Warning, computer nerd stuff only, but it could be useful…

Occasionally, Gaia GPS has a hard time importing / uploading a GPX file direct from Google Drive. This is often because of an “XML “ tag in the first line of the file. Sometimes when Google sees this XML code, the file is not recognized as being a GPX and you are not given the option of the Gaia app to open it.

There are two workarounds for this that I’ve found.

Workaround #1 is to use method one above,: download the GPX file to your desktop, and then upload it to your account at GaiaGPS.com.

Workaround #2 is a little more involved. Open the GPX file in a text editor, and it should look something like the file below (which is a small one of about 10 waypoints.)

Notice the highlighted text in the very first line? Delete all the text between the <brackets> plus the brackets. Save as a new file name, move it back to Google Drive, and it should work fine Google Drive to your Gaia app using the “Open In” method above.

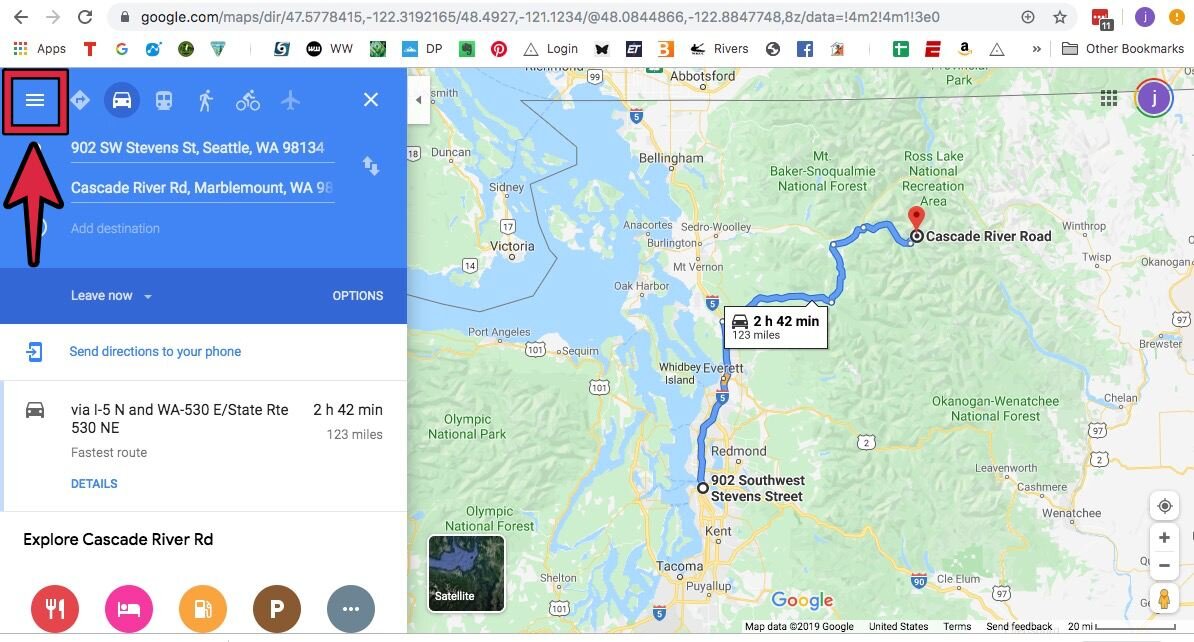

Google maps to GPX file with MapsToGPX.com

If you find yourself driving a lot to remote trailheads without good cell coverage, you may find that Google maps and driving directions don't always work so well. Here’s a cool way to make a GPX track from Google driving directions, which you can follow on your phone or GPS device without cell coverage.

Thanks to my friend and expert boondock backroad navigator Daniel Mick for this tip.

Navigation on a hike or climb is more than what you do with your feet. Driving to an obscure trailhead can sometimes be the navigational crux of the whole trip. Mapping apps work great in town when your destination has an address, but what if you're looking for a trailhead or campground?

If you have the latitude longitude coordinates of a trailhead (or anything else) you can copy/paste the coordinates into Google maps and get driving directions and a map to the trailhead. (Learn how to find lat long coordinates for anywhere at this article.)

If you have decent cell coverage, this should be all you need. But in more remote areas, Google maps sometimes falls short, and you may want to take this extra step of following a GPX track instead.

Below, learn how to create a GPX track file from a Google map. (Like most things in life, it's easy once you know how.)

Why is a GPX track an improvement over the normal driving directions in Google maps?

Outside of cell phone coverage, Google maps can do some strange things. The map detail can be significantly reduced, even if you download the map. Google maps has no terrain or contours shown, so it can be trickier to see your precise location.

However, once you have a GPX track of your driving route, and a quality GPS app on your phone like Gaia GPS, you can choose whatever map base layer desired (topo, satellite, Forest Service, Open Street Map) you like. You can annotate maps with additional navigation notes, such as good car camping spots, locked gates, private property, etc.

You can also record a track of your route when you’re driving. This can confirm your exact location, which fork you took on that last intersection, and keep a record of any change in your route (locked gates, washouts, logging road change, etc.)

If you find yourself driving to a lot of remote trailheads far away from cell phone coverage, this might be a good navigation trick to have in your toolbox. This might look a bit complicated when you first read about it, but after you get the hang of it it really takes just a few minutes.

For the example below, we’ll use driving to El Dorado Peak, a popular climb in the North Cascades in Washington.

Here’s how to do it.

Step 1 - Find the latitude / longitude coordinates of your trailhead.

Probably the easiest way to find the coordinates of a trailhead is to have a GPX file of the entire hiking or climbing route. Import this GPX file in CalTopo, notice where one end of the track reaches a road, right click at that point, choose New > Marker, and copy the coordinates that appear in the box in the lower right corner.

(Note: There are three different formats of latitude longitude coordinates. By far the easiest one to deal with is called decimal degree coordinates, which look something like this: 45,1234, -122,1234.)

For example, the El Dorado Peak trailhead has lat/long coordinates of: 48.4927, -121.1234

Step 2 - Copy and paste these coordinates into the Google Maps search box. Click Enter.

Step 3 - Click “Directions”. This should give you driving directions from your current location to the trail head.

(Tip - If you don't need directions right from your front door, you can click and drag the little dot at one end of the direction line to a new location. Below, I moved it from Portland to Seattle to simplify things.)

Step 4 - Click the “3 horizontal bar / More” icon in the top left corner.

Step 5 - Click “Share or Embed map”

Step 6 - Copy the "Link to share” URL

Open a new browser tab. Go to “mapstogpx.com”.

Paste the Google directions “Link to share” URL into the box.

Click “Let’s Go”. This should download a GPX file of the Google driving directions.

Open caltopo.com and import the GPX file. It should draw correctly, as seen below.

Make any edits or additions to the driving route, such as locked gates, camping or meeting spots, sections of rough road, any known closures or detours, etc.

When you're all done, export the GPX file from CalTopo and save it to your computer.

Now, you can put the GPX file onto your phone or GPS device for confident navigation outside cell coverage. If you use Gaia GPS, which is my favorite backcountry GPS app, the easiest way to get the file to your phone is to go to Gaia GPS.com, click your username in the top right corner, and choose “Upload” from the drop-down menu. This will sync the file from GaiaGPS.com to your phone app.

Finally, here's what the track looks like after importing it to my Gaia GPS phone app. It’s a perfect track to follow to the trailhead, even without cell coverage.

View snow levels and your route in Google Earth

Wondering how much snow is on your intended hike or climb? Learn how to view your route and an overlay of current snow levels in Google Earth.

Thanks to Alpinesavvy reader Lucas Norris for introducing me to this great tip.

Upfront disclaimer, this article is generally for people who are pretty geeky about maps. Hopefully you’re one of them. =^)

In a previous article, we covered how to download a map with real time snow depths in the US and part of Canada. This is a pretty handy tool for trip planning, but there's potential to make it even better.

What if you could see this snow depth data overlaid onto your actual drawn route, AND in the 3-D splendor of Google Earth? Turns out you can. Here's how to do it.

Tip - I have not tried this in the web browser version of Google Earth, only on Google Earth Pro, which is free software you can download onto your desktop computer. I recommend doing this in Google Earth Pro.

For this example, we’ll be using the Wonderland Trail around Mount Rainier.

Step 1 - Get a GPX track file of your intended route. We cover how to get track files for climbing at this article, and for hiking at this article. You can find a track for the Wonderland trail at the “Pacific NW Long Hiking Routes” section right here at Alpinesavvy.

Step 2 - Convert the GPX track file to a KML file, a type of file that plays well with Google Earth. One easy way to do this is to go to caltopo.com, import your GPX file, and then export it as a KML file. Use the Import and Export menu bars at the top of the screen.

Step 3 - Import your KML file to Google Earth. Launch Google Earth. Double click or drag and drop the KML file into Google Earth. It should draw up as a red line and look something like this. (Yes, pretty damn cool!)

Step 4 - Get the snow data. Go to this website.

https://www.nohrsc.noaa.gov/earth/

You probably want the most recent data, which will be the top of the left column, under “Snow Analysis Overlays.” In the image above, that would be the link for November 18. (You can also see historical data under the “Archive” link at the very bottom.)

This will download a KMZ (another filetype that plays well with Google Earth) file of the snow data to your hard drive. Double click on this or drag and drop to open in Google Earth.

Very cool! This is the real time snow cover over the entire United States and most of southern Canada. (As I write this in mid November 2018, you can see it's been a very light snow year so far in the western United States.)

Step 5 - Zoom into Mt Rainier. With the snow depth level data loaded and a KML file of your route also loaded, your screen should look something like this.

It appears it if you wanted to get in a late November hike in 2019 of the Wonderland Trail, you should be able to do it with hardly any snow, kind of a rarity here in the Northwest.

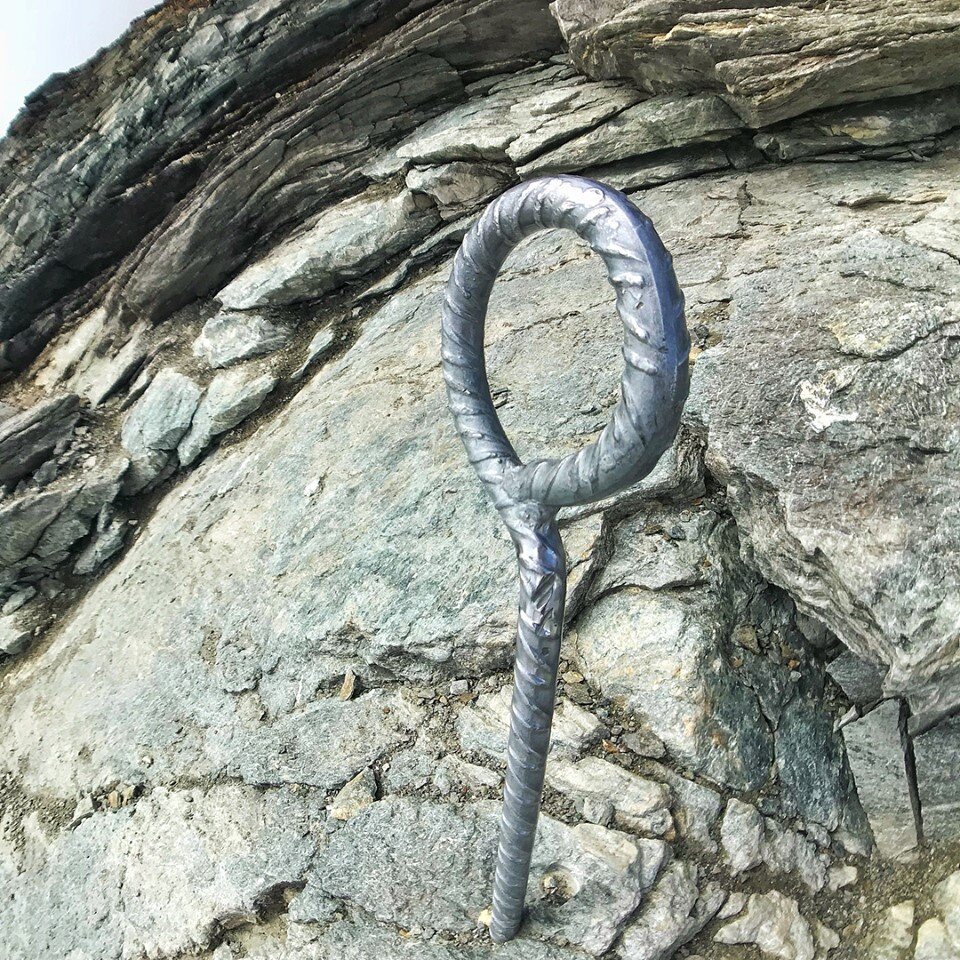

Thoughts on redundancy in climbing anchors

Redundancy is one of the tenets of anchor building, for good reason. It's a great rule for most climbers in most situations. But, it’s actually more of a situational and subjective guideline than a black and white rule. Learn some of the factors that may influence this choice, and see some examples of non-redundant anchors in action.

This article was written with editorial assistance from Richard Goldstone, thanks Richard!

Redundancy in anchors, while a good maxim for most climbers in most cases, is a situational and not an absolute rule.

One of many single piece, non redundant anchors on the Matterhorn. Photo by Dale Remsberg.

Single point, non redundant anchor on the matterhorn. photo: Dale Remsberg

“Good judgment comes from experience. Experience often comes from surviving bad judgment.”

Will Rogers

One of the core concepts of anchor building is redundancy - if any single component were to fail, the entire anchor wouldn’t fail. This mandate has been around for a long time for a good reason, because it's arguably the single best thing relatively newer climbers can do as a buffer against the mistakes of inexperience. The sketchier the situation, the more redundancy counts. When in doubt, double up isn’t a bad rule to live by. If you have the gear and the time, do it.

Sliding X anchor? Not redundant. If that sling gets cut, adios.

Statically equalized cordelette style anchor? Perfectly redundant, if any part of the sling fails, the rest of the anchor still works.

However, outside of anchor construction, climbing has many mission critical components that are not redundant.

Most of us climb on one rope

Pretty much every harness has one belay loop (Yes, it's doubled over and sewn, but it's still one piece of webbing)

We belay and rappel with one carabiner, with one belay device

We clip the one bolt/hanger with one carabiner/draw as the first clip on a sport route, and would deck if it fails

You get the idea. Why do we accept so many potential “single points of failure” in many parts of the system, yet demand it always be a component of our anchors?

The answer is, it doesn’t always have to be. Rather than being a mandate for every anchor, all the time, think of redundancy as a concept that applies in varying degrees to varying situations. It’s overall a good idea, and you should never be faulted for doing it, but it’s a situational, and not absolute, rule.

IFMGA Guide Dale Remsburg writes: “The idea of redundancy comes from pieces in the rock, not the links or tools we use to connect them.”

Keep in mind, creating redundancy comes at a cost of time, or gear, or both. Mostly, that’s a good tradeoff to make. Other times, perhaps not.

A fundamental principle of economics (and many other aspects of life, including anchors) is the law of diminishing returns, which, in econ-speak, means that adding additional factors of production eventually results in smaller increases in output. Say that it takes one builder one year to build a house. So, if you have 365 builders, can you build a house in one day? Of course not, because after a certain point, the extra production (builders) result in lower output (less work getting done because they are tripping over each other).

And yes, this can apply to building anchors. Continuing to add “production” (additional slings, backups, double locking carabiners, etc.) at some point do not significantly increase your “output” (safety margin), so it's probably not so smart to keep doing it. Of course, the question becomes, where do you cross that point? There's no firm answer, but here's one way to think about it mathematically.

Say that the odds of failure of an anchor sling are one in 1,000. If you backup that sling with another, the theoretical odds of anchor failure become 1,000 x 1,000, or one in 1 million. Add a third sling? The theoretical odds of failure are 1,000 x 1,000 x 1,000, or one in 1 billion.

What's your acceptable level of risk? If you're feeling good with one in 1,000, then going to one in 1 million (let alone 1 billion) is probably not worth doing.

Another broad component of anchors is having proper context in anchor photos/examples. This gets more into the situational judgment of when redundancy is more important. It's tricky to simply show a photo of an anchor and ask if it's acceptable or not. The slightly snarky yet truthful answer is, “It depends! Some broader context questions might be:

Is the anchor for a multi pitch lead belay, top rope anchor or a rappel anchor? Loads vary a LOT between these. Peak force on a rappel anchor, 2-3 kN; theoretical max force on a lead anchor, about 9kN. (Source)

How difficult is the pitch below or above, and what’s the skill level of the climbers?

Is it a part of multi pitch climb or the top of a climb?

Is there a chance of rock or ice fall that might hit the anchor?

Is it a casual day at your local crag, or are you trying to do a remote 15 pitch alpine route?

And so on.

Let’s examine that last point - that of speed/efficiency. When people cut corners on anchor building, the usual rationale is that it saves time and/or uses less equipment. Let's be honest though, the requirements for “speed” on a relaxed three pitch climb on a sunny day at your local crag (where time, weather, and daylight are not major issues) is minimal. On a casual route with no real need to hurry, eliminating redundancy from an anchor because it saves you a few minutes is not a very compelling argument.

How about a long, committing, 15 pitch alpine mountaineering route? There, shaving off a few seconds wherever you can might become more important, because the time savings multiply over the course of a big day.

Some people always seem to be in speed mode, striving to do everything the quickest way possible. If that works for you, great. But, for most of the rest of us, and especially for newer climbers, safety should always be a priority over speed.

Let's have a look at a few anchors that question the concept of redundancy. How do you feel about them? Consider the trade-offs in time, gear or both to make the anchor “textbook” redundant.

Rappel anchor

One tree, one sling, one carabiner. Every part of this anchor is non-redundant.

However, each of these three components is vastly stronger than any possible rappel load, which at most, even with terrible rappel technique, is never going to exceed 3 kN.

The tree is well rooted and stout enough. (Some folks use “5 & alive” for tree anchors - at least 5 inches in diameter, and alive.)

Some brand new 1 inch webbing (rated about 18 kN) tied in a well-dressed water knot with good long tails. The webbing is rubbing on tree bark, not the sharp edge of a rock.

Snapgate carabiner (rated 22 kN) left behind for the rope connection, gate taped shut for extra security (aka cheapskate locker). Extra points for using pirate hockey tape.

So, whaddya think? Would you rap on it? Why or why not? If not, what would you change / add so you’d feel comfortable?

How about this anchor? It’s a Fixe PLX/Duplex anchor, standard in many parts of Europe and Canada, but not so common in many parts of the USA. Everything is stainless steel, the rings are 10 mm thick, and the whole thing is rated at 30 kN.

How about that bottom ring? The gear testing wizards at HowNot2.com tested a couple of these. One broke at around 90 kN, the other broke around 60 kN! That is miles stronger than your rope, your belay device, your belay carabiner, and all those other single points listed above. If you're happy with those single points, why not be happy with this?

This is an anchor that can leave redundancy advocates scratching their noggin. Hmm, what do I do with this mishmash of hardware? Am I supposed to clip just that ONE ring at the bottom?! That’s not redundant, if it fails, YGD! (You’re Gonna Die).

Redundancy advocates might just ignore the chains and ring, and rig this with a long runner clipped to the bolt hangers. Remember, it's probably totally fine if you choose to do this, but it’s not the intended nor most efficient way to use this style of anchor.

Here’s an Instagram video posted by AMGA Certified Rock Guide Cody Bradford using this exact style of anchor. Cody clips a single large locking carabiner to the ring making a master point, then clips two carabiners onto that, one for his clove hitch and one to belay his partner. Yep, everything off the one ring. (And then everything off of one yellow carabiner.)

Not textbook redundant, right? What do you think about this anchor set up? What would you do with anchor hardware like this if you had to belay up your partner?

Here’s another example. I first saw this anchor on the Facebook feed of Dale Remsberg, an IFMGA Certified Guide and technical director of the American Mountain Guide Association. (So yeah, Dale knows his stuff.) It's a photo he took of an anchor he built while guiding a client, and put it on Facebook to start a discussion about, guess what, redundancy. (For context, it’s on a large ledge, the pitch below is an easy 5.7ish, and there is no risk of rock fall from above.)

image: Dale Remsberg - https://www.instagram.com/p/BxH139Tj1M5/

What do you think of this?

At first glance, redundancy advocates would dismiss this immediately. A basket hitched sling has zero redundancy; if it gets cut or fails, immediate anchor failure and YGD!

Technically true, but how would this sling possibly fail? It's running around tree bark, not any sort of sharp rock. There is zero risk of rockfall from above impacting the sling. The only way it could fail for is for it to physically break, something that has pretty much never happened in the history of rock climbing outside of the ever awesome Sly Stallone movie, Cliffhanger. (Readers, please correct me on this last sentence if I’m mistaken.)

One approach to make this anchor redundant is to tie a knot in the sling. Maybe so, but what's the trade-off? You might barely have enough sling material to make the knot . . . or perhaps you wouldn't. You also weaken the sling by tying a knot. You also take the time to tie the knot, and probably a longer time to untie it, which if it gets weighted, could be a hassle. (Side note: could be a great place for a girth hitch at the master point.)

Which is more important, having the full strength of the runner, or weakening it by tying a knot which creates redundancy? Oh, and there’s just one tree branch there, that's certainly not redundant. What about that?

Now, I saved that's the best for last. Here's one that’ll give redundancy advocates nightmares. (And to be honest, I’ve never seen one of these in real life and I'm not super excited about it either . . . )

How about ONE SINGLE BOLT?!

Here’s a screen grab from a video, link below. From the video: “( . . the anchor can) . . . in some instances be a single large glue in bolt, which is the only anchor at the anchor point.”

How are you going to make this redundant? Answer is, you probably can't.

image : screen grab from: https://youtu.be/1r7hIZREJoQ?t=

Now, before you start thinking this is a 20 year old photo from East Boondockistan, this video comes courtesy of the excellent (if awkwardly titled) “Safety Academy Lab Rock” video tutorial series, produced by the well-regarded German company Ortovox, and backed by Petzl and the German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (in German, “VDBS”). So, while if Americanos like me may not have any personal experience with it, the fact that it’s featured in an instructional video made by VDBS I’d say give it a fair bit of cred.

And no, you don't truly know the quality of the steel, the length of the bolt, the type of adhesive used to glue it into the rock, etc. But, a properly placed long glue in bolt like this has a UIAA minimum standard downward pull of 25kN, and have actually tested up to 50(!) kN, which makes it about the strongest component you'll pretty much ever encounter in climbing (right up there with the huge master point ring in the Fixe anchor above.) So, the short answer is yes, you can probably rely on this single point of connection. (But, in all honesty, as an American climber raised with the mantra of redundancy, I would not be overjoyed to discover this as my only connection to the rock.)

But hey, if you find this at the top of the first pitch and you don't like it, you can always rappel off and go climb somewhere else, right? :-)

Below is the whole video; see the single point anchor part starting at 0:40.

(And the fixed point belay? We’ll cover that soon in another Alpinesavvy article.)

And, for a little historical perspective, here’s one of many single piece anchors on the iconic Matterhorn, photo by Dale Remsberg.

Stout? Looks like it.

Used by probably tens of thousands of climbers over decades, most of them professional guides? Yes.

Redundant? Nope.

anchor on the matterhorn. photo: Dale Remsberg

CalTopo - Use the “Bearing Line” tool as a peakfinder

Climbers love to politely argue, from a sunny summit, the question of ”What’s that peak?” Here's a way to answer that question with the great mapping software CalTopo, but you'll have to wait till you get home.

(If you want to learn the basics of using CalTopo, start with this tutorial video.)

One of the eternal things climbers love to argue about sitting on a sunny mountain top is the game of “What's that peak?”

Now, you could use a clever smart phone tool such as the app “PeakFinder”, but here’s another method.

Take a compass bearing from where you are to the mountain top (or other landscape feature, like a lake.) If you just have your smartphone, there should be a compass app on that. Take a screen grab to remember the bearing.

When you come home, open up CalTopo.com on your desktop, Right click the location where you took the bearing, and choose New > Bearing Line.

Enter the bearing and distance in the dialog box. Usually you don’t know how far away the peak is, so enter a huge distance, like 100 miles.

CalTopo will draw a line from the start location on the bearing and distance you specified. If it runs through (or close to) a major mountain, you have your answer.

Here's a recent real life example. A friend of mine who lives in Bend Oregon took a walk to the top of Pilot Butte one evening, a local high point in town. Far off in a general SW direction, he saw the tip of a mountain pointing up that he had never noticed before. What could that be? He took a compass bearing to it, and the resulting CalTopo bearing line map looked like the top of this page.

Answer: Mt Thielsen.

Use 2 carabiners to fix a broken backpack waist belt

A broken waist belt buckle can be a substantial problem on a remote trip with a heavy pack. However, with this clever tip, you can probably fix it with just two carabiners.

Breaking the buckle on your backpack hip belt is pretty common, and can be a rather serious problem.

Here’s a very crafty way to fix this, courtesy of Alpinesavvy reader Andy Sorenson. (Andy happens to be a mechanical engineer and product designer, which sound like the perfect skills to have when you break something in the woods. Connect with Andy at mindsparkdesign.com.)

Arrange two carabiners as shown below, thread the webbing through them, and cinch down. The friction from the carabiners holds the webbing snug. (Depending on the width and slickness of your webbing, your mileage may vary; it worked fine for me. )

While this works as a temporary repair, having an inexpensive and lightweight spare buckle in the repair kit is a fine idea if you’re on a longer trip/expedition.