Alpine Tips

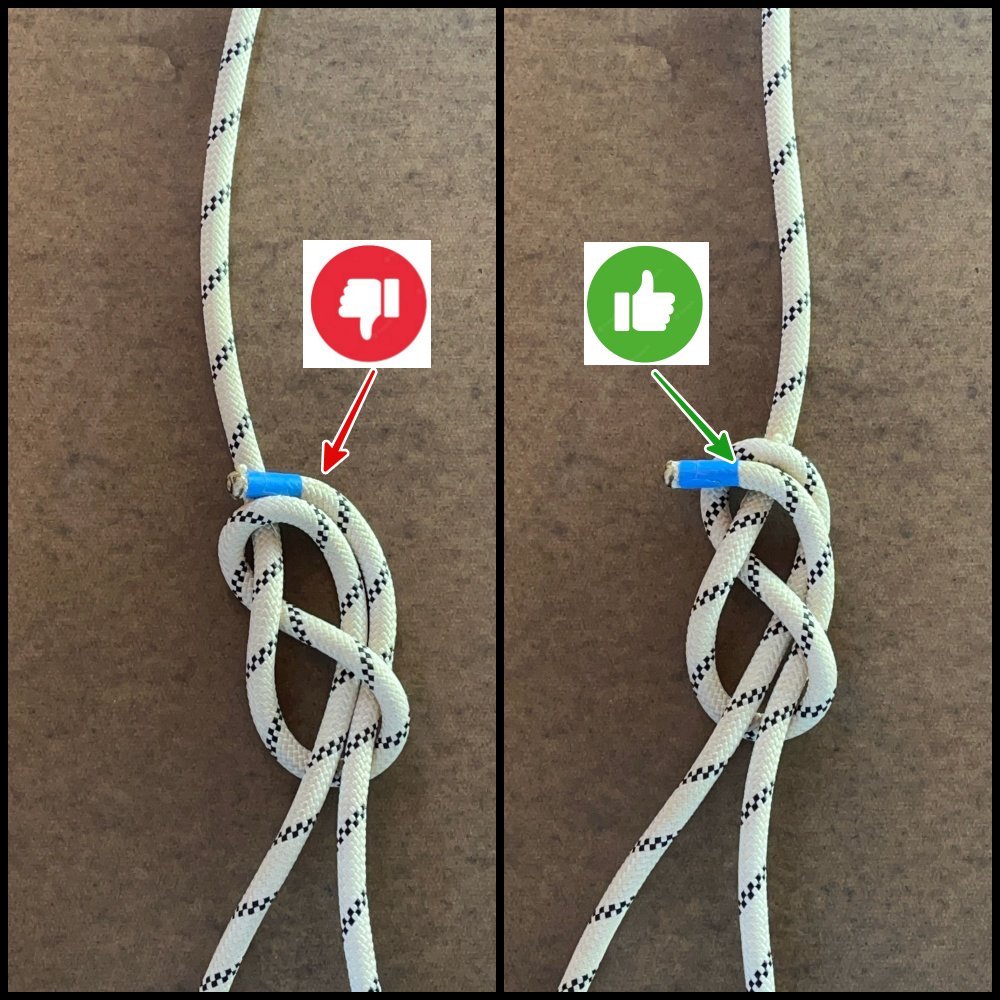

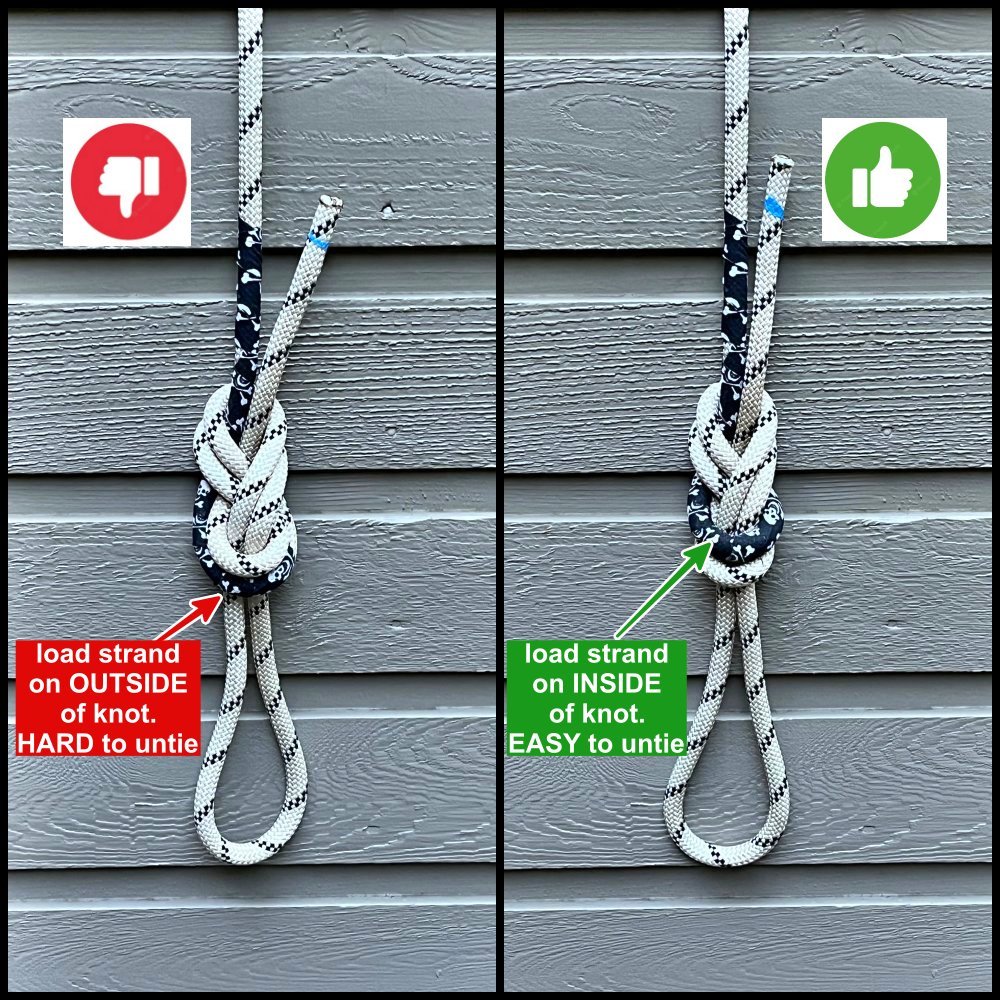

Don't trap the rope ends under a strand

On a double rope rappel, It's good practice to keep the knot tails from getting underneath either of the rope strands. If they do, it can add extra weight and friction and make it quite a bit harder to pull your rope. Simply have the knot tails hanging free and you should be fine.

If you have a rappel that starts on a lower angle slab instead of more free hanging, it's good to be mindful of where the rope tails are laying.

On the left, the rope tails are underneath a strand. The extra weight on the tails from blue can make it harder to pull green.

A better way to do it is on the right. Simply have the rope tails laying away from the two ropes and you should be fine.

This can become more of a factor if:

you’re on high friction rock like sandstone

if your rope is wet, which is common in canyoneering.

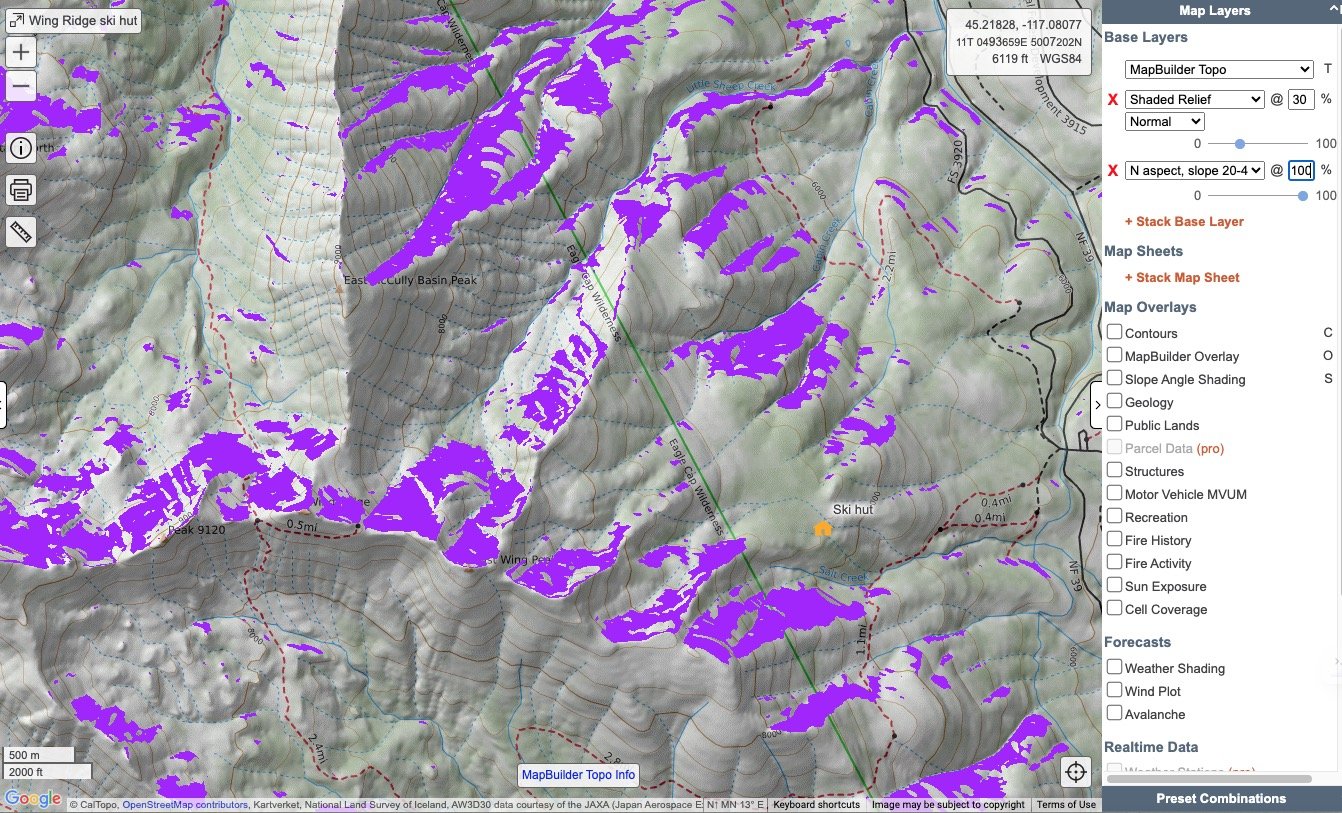

CalTopo pro tip - Custom terrain shading

CalTopo, the best desktop mapping tool for backcountry users, has a very cool feature - custom terrain shading. Once you get the hang of this, you can make custom map overlays showing slope angles, aspect, elevation, and more. It's fun and easy! Learn how from this tutorial.

CalTopo, the BEST desktop mapping tool for backcountry travelers, has a very cool, seldom used feature: custom overlays of various combinations of slope angle, aspect, elevation and canopy cover. The interface can take some practice, but once you get the hang of it, it’s easy and powerful.

(This is based on what cartographers call a “Digital Elevation Model”, or DEM. In simple terms, it’s a three dimensional model of the world used in digital mapping.)

If you'd like to follow along and try this yourself, create a free CalTopo account, which lets you access a majority of the mapping tools. If after trying DEM shading you think this software is terrific, please consider an annual subscription (starting at $20) to support the small team of developers making this great tool available, hint hint.

Here's how to use CalTopo DEM shading.

Are you doing some off-trail travel want to avoid areas that are excessively steep? Check out the example in the photo above: all slopes between 35 and 90° get a color.

Backcountry skiers can really get some benefit from this tool, so that's the example we’ll use from now on; the Wallowa mountains in northeastern Oregon, a popular place for ski touring. There are several yurts and huts that can be reserved for winter adventures. (I’ve never been, but I’ve heard great things about it.)

If you want to follow along and use the same area I am, here are the coordinates of the ski hut. Copy paste these into the CalTopo search box.

45.2037, -117.0938

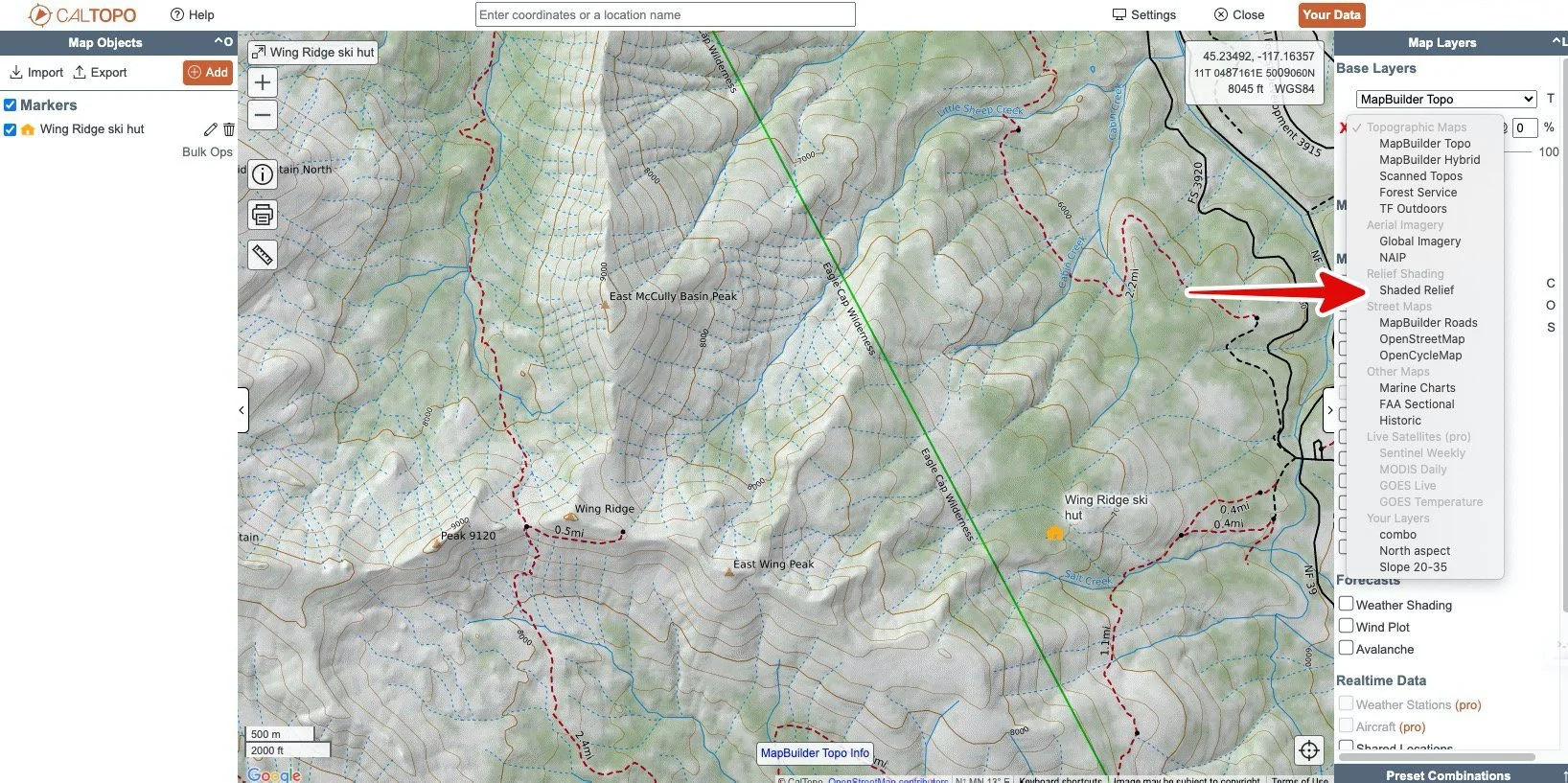

First, let’s add shaded relief to the default base layer of MapBuilder Topo. It already has a little, but let's add a bit more so we can more easily see ridges, gullies, aspect, and terrain features.

From the “Map Layers” menu in the top right, click “Stack Base Layer”.

From that drop-down menu, click “Shaded Relief”.

Play with the slider bar to adjust the opacity between zero to 100% . As you slide the bar to the right, you should see increased shading added on to your base map. I like something in between about 30 and 40%. Use what looks good to you.

Shaded relief is extremely cool, and it's a nice thing to add almost all of your maps!

Excellent, we have our base map with extra shaded relief. Let's add some custom DEM shading.

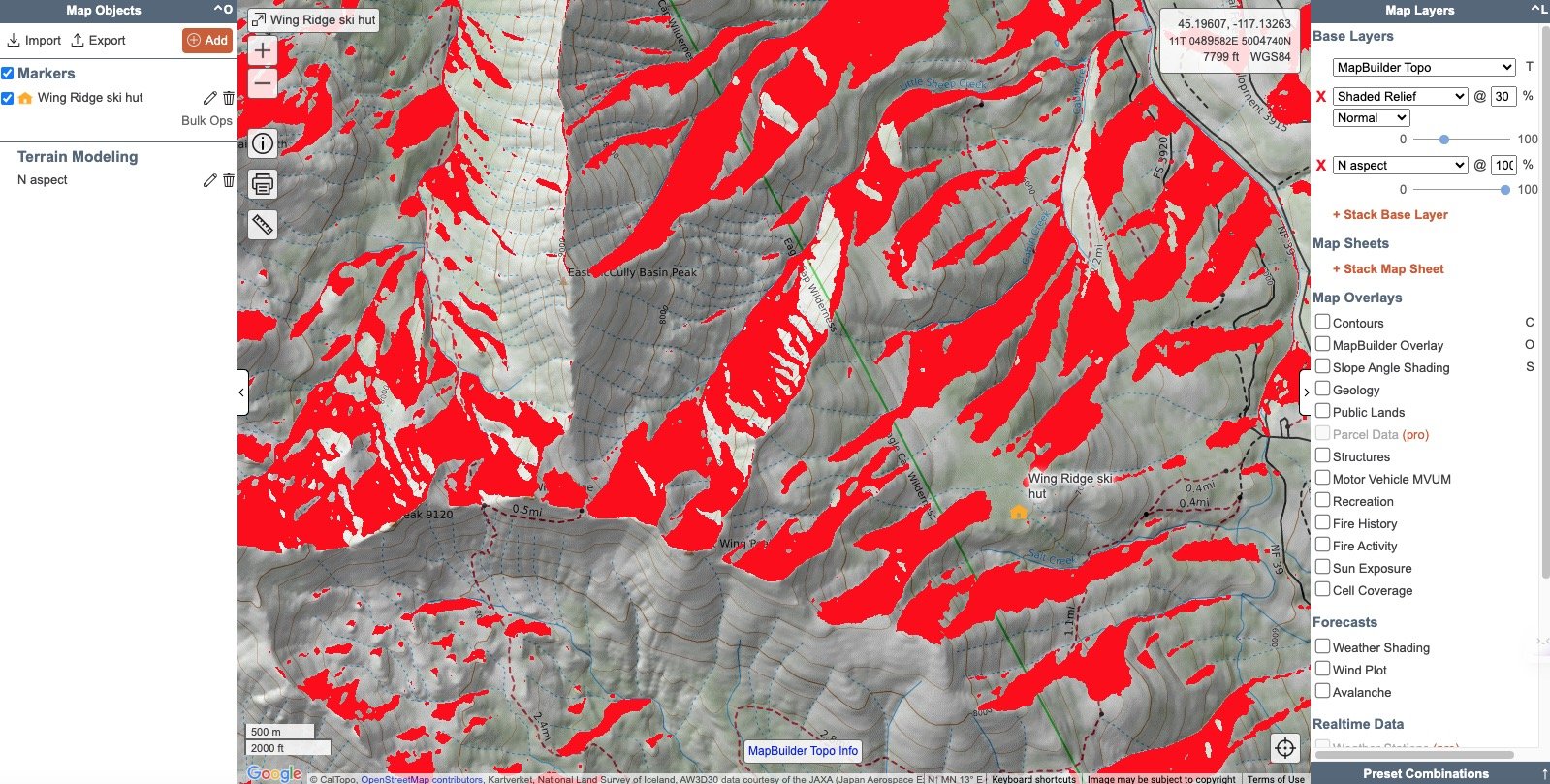

Say we’re headed in to the hut for a few days of skiing, and we’re interested in slopes that are north facing. Here’s how to show that in a custom DEM overlay.

Zoom in to your area of interest. Choose the “Add” button from the top left corner.

From the drop-down menu, select “DEM shading”

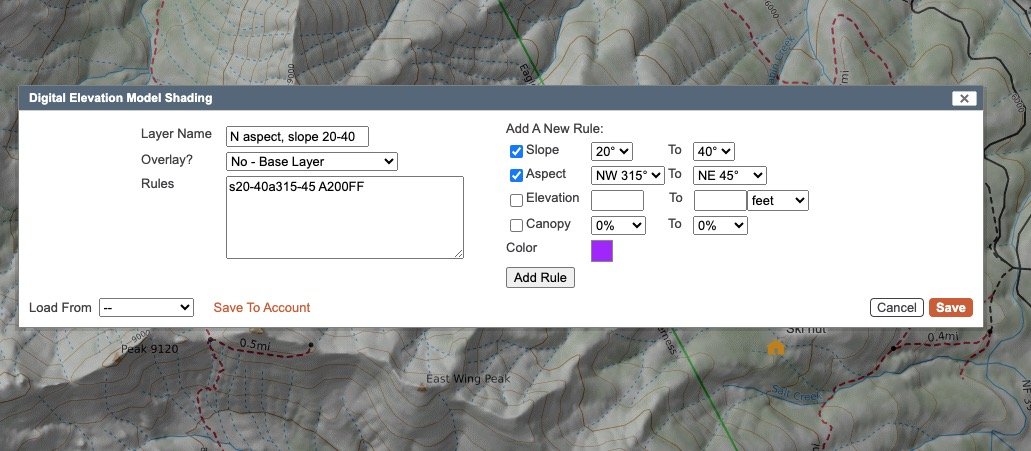

Here's where the magic happens: “Add a New Rule” to generate your overlay.

Check the box next to “Aspect”, and select “NW 315” to “NE 45” from the dropdown menu.

Click the Color box and set the color to red for both NW 315 and NE 45.

Add a descriptive name in the top left corner, here, “N aspect”.

In the “Overlay?” box, select, “No, Base Layer” from the drop down menu.

Click “Add Rule” to generate the code CalTopo needs to make your map.

Click “Save to Account”.

Finally, click “Save”.

Voilà! You should now see an overlay on your map showing all north-ish slopes colored red.

Notice that because we chose “Base Layer” in the previous step, our named overlay has been added as an overlay, sort of like tracing paper, over the top of the base map. You can see this at the top of the menu on the right side.

Ouch, that red is hard on the eyes! In the top right corner, use the slider bar to set the opacity to a lower level. I like something between about 30 and 40%. That's easier to look at, and lets you see underlying map features.

Because you clicked “Save to Account”, this custom overlay is saved. This is slick, because you can use this overlay on any future map without recreating the rule. Here's how to find it.

Click the orange “Your Data” button in the top right corner.

Then, click the “Your Layers” tab. You should see the layer called “N Aspect”.

To use any saved custom DEM shading in the future, open a map, select “Stack Base Layer” from the top right side, and click the drop down menu. You should see your saved layers under “Your Layers”.

Okay, are you getting the hang of this? Nice!

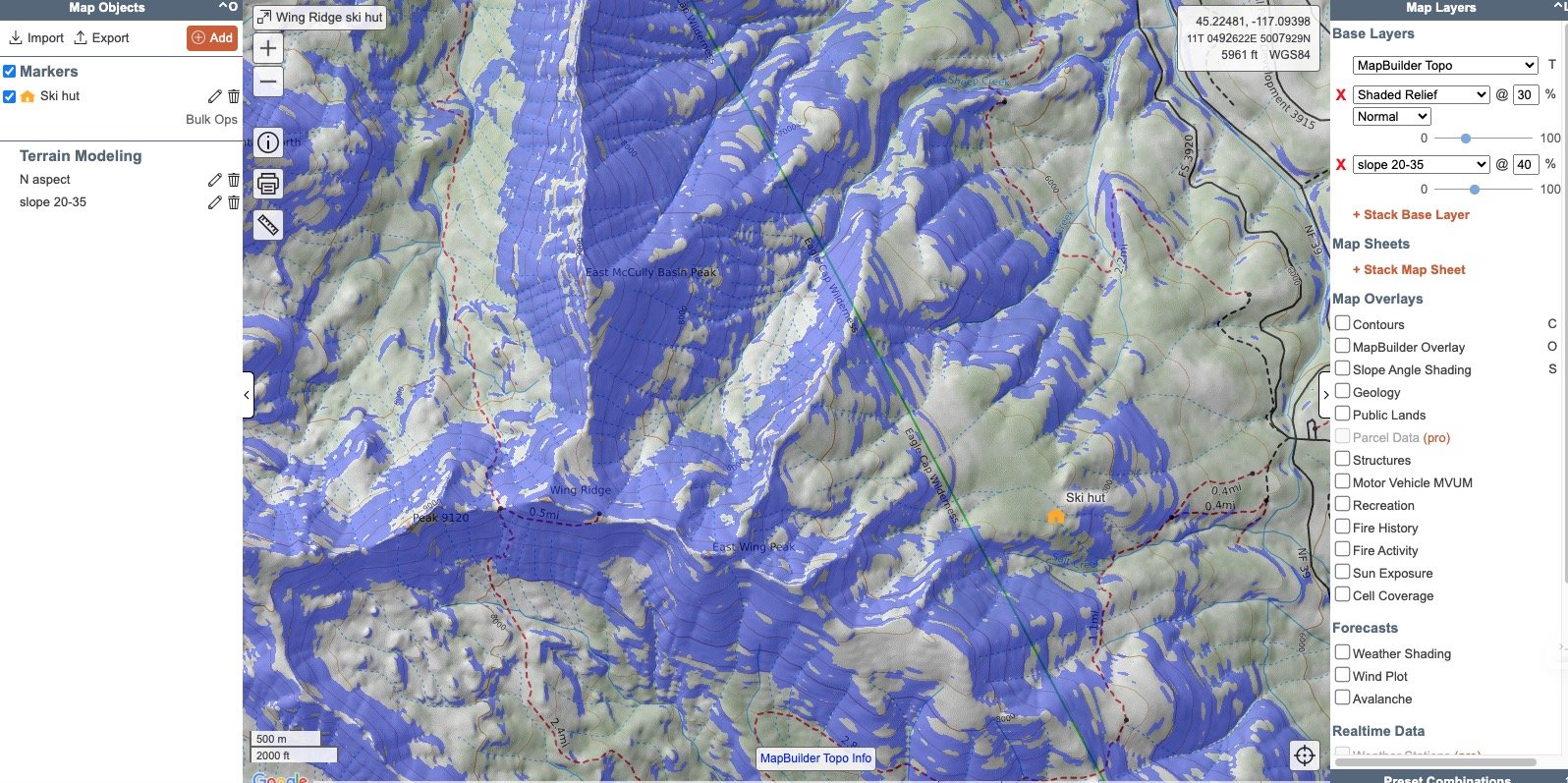

Let's make another overlay, this time for slopes between 20 and 40°.

As before, click the ”Add” button in the top left corner, select “DEM Shading”, and put the following into the “Add a New Rule” box.

That should generate a map looking something like this: all slopes between 20 and 40 degrees.

Maybe you're looking for flat places to camp?

No problem. Make a custom layer showing all areas with slopes between 0° and 5°.

Here’s the resulting map, showing flat areas with 50% opacity.

Let's make an overlay that shows a specific aspect AND slope.

Say you want to ski in the following terrain:

north facing slope

slope angle between 20 and 40°

Here’s the rule that generates an overlay for that.

That rule generates this map: north facing aspect with slope angles between 20 and 40°.

Schweeeet, looks like there's some great terrain very close to the hut.

Create an elevation gradient DEM overlay

You can also use a pair of colors to create a gradient between a single condition, here elevation.

Let's make a gradient DEM shading with these elevations and colors:

Terrain between 5,000 and 7,000 feet, light green to green

Terrain between 7000 and 10,000 feet, green to purple

First, we make a rule for elevation 5K to 7K, and use the color picker to select light green to green. Click “Add Rule”, and the code is generated.

Next, create a second rule: change elevations from 7K to 10 K, change the colors from green to purple, and click “Add Rule”. Notice a second rule is added as a new line in the “Rules” box.

You can do this for as many different categories as you want. For example, if you wanted to show slope angle between 25 to 30, 30 to 33, 33-36, etc, keep adding rules and changing the colors.

The elevation gradient overlay looks like this. Nice! It looks even better on a big screen, give it a try!

So, that's a pretty detailed tutorial of custom DEM shading in CalTopo. Play with it, save your overviews, and, as suggested before, please consider a modest subscription (starts at $20 annually) to support the development team making this great tool available.

If you made it this far, here's a small bonus. Yes there's international coverage!

Here's a portion of the classic Haute Route from Chamonix to Zermatt, with that 20% to 35% slope shading added.

Backside clove hitch: transition to "self-thread" lower

The “backside clove hitch” offers several options for efficient transitions from climbing to descending. Here's one way to use this tool: the second is lowered with an ATC on the anchor and the rope through the anchor hardware. This sets up the rope perfectly for the leader to rappel.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

Transitioning from climbing up to rappelling down is often a complicated and time-sucking part of your climbing day.

The traditional method of each climber using a leash to connect in close to the anchor, each person untying from their respective ends of the rope, threading the anchor and then each person rigging for a rappel separately can be awkward at tight stances and often takes a lot longer than necessary, especially with less experienced folks.

There are several different techniques to increase efficiency. Here’s one of them: lowering the second climber to set up the rope for the first climber to rappel.

The leader arrives at the top anchor, builds an equalized anchor with a master point (say a quad).

The leader clips their climbing rope with a clove hitch to the master point.

When the second arrives at the anchor, instead of clipping to the anchor hardware with a tether, instead they clip to another clove hitch on the backside of the leader’s clove hitch connection.

This frees up the second’s end of the rope.

The second unties, threads the rope end through the anchor hardware, and re-ties into the rope.

Next, you rig a lowering system for the second, typically with an ATC on the anchor.

Now , when the second is lowered, half of the rope moves through the anchor hardware, which perfectly sets up the next person to rappel. Hence the name, “self thread lower”, schweeeeet!

(This is closely related to the backside clove hitch transition to rappel, which we cover at this article.)

Like many things in climbing, this is a much better show than a tell. Watch the two video clips below to see how it's done.

Why lower instead of rappel?

Low angle, blocky, rope grabbing terrain that makes throwing a rope problematic.

High winds, which could cause some big problems if you throw your rope.

You may not know exactly the distance to the next anchors. Lowering can ensure the first person gets there and does not find themself dangling in space at the end of the rappel. (Then you probably need to do the #CraftyRopeTrick of an extended rappel, which we cover in this article.)

Maybe a beginner climber who’s not comfortable with rappelling.

Many climbers are hesitant about being lowered from above. Interesting that these same climbers have no concerns with top rope climbing, when you are lowered from below, so what's the real difference? Yes the rigging is a bit different, and you need to practice that for sure, but in the end it's functionally about the same.

For this to work:

You need to know your descent and be SURE you're able to make it to the lower anchors or ground with at least half of the rope left. (If you just climbed the pitch and the belayer did not pass the middle mark, you should be fine).

On a multi pitch rappel, you need to be sure that the first person down can safely secure themselves to the anchor, which might be a concern with a beginning climber.

You need to have a good middle mark on your rope.

Assuming these requirements are meant, you can see from the videos below what an efficient technique this can be.

It might appear that this technique puts extra wear and tear on the anchor hardware, because it seems you're lowering directly through it, which is generally not best practice. Turns out, this is not the case. Almost all of the friction from the lowering is happening on your belay device, and the rope is simply redirected through the anchor hardware that's higher up.

From AMGA Rock Guide Cody Bradford.

Sadly Cody is no longer with us, but his excellent Instagram account is still up, highly recommended for many other climbing tips like this. Rest in peace, my friend.

https://www.instagram.com/reel/CbqClsZhOXc/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Nice YouTube short from Summit Seekers Experience showing this technique:

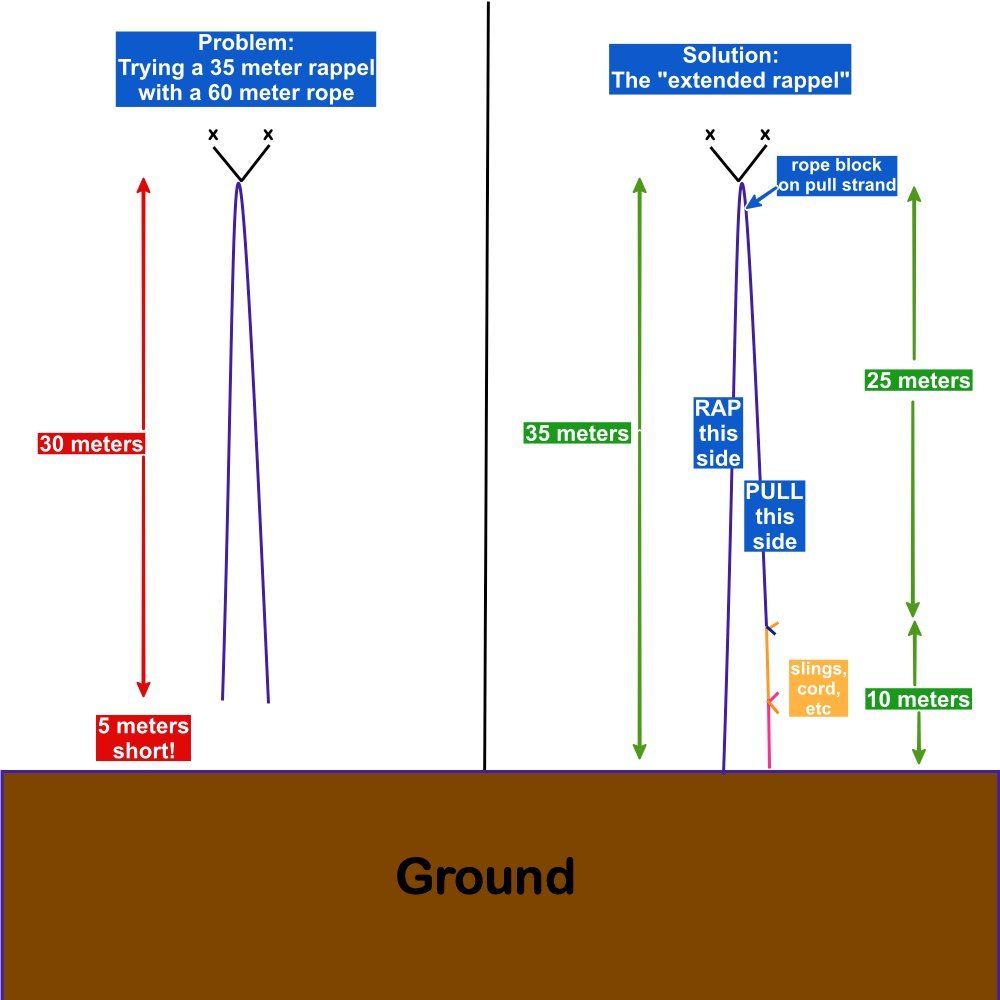

The "extended" rappel

You and your partner have a 60 meter rope, but you need to make a rappel that was bolted for a 70 meter rope. Yikes, your rope is too short, whaddya do? One answer: the extended rappel. Learn how it works, along with some cautionary notes.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

This article was written with collaboration from Sean Isaac. Sean is an ACMG (Association of Canadian Mountain Guides) Certified Guide, a former professional climber, and author of the “Ice Leader Field Handbook” and “How to Ice Climb” (2nd ed.) Follow @seanisaacguiding for tech tips. Thanks, Sean!

Here are articles on two closely related techniques that use rope blocks:

Your rope is too short, what do you do?!

You’re rappelling from a multi-pitch rock climb with a single 60 meter rope. All pitches on the way up were less than 30 meters except one that was 35 meters long. (You know this because your attentive belayer noticed the middle mark going through the device before the leader arrived at the next anchor. Another great reason to have a middle mark!)

Whoops, should've read the guidebook and brought the 70 m instead of the 60 m, but here you are.

How do you rappel and still pull your rope? (This is an unexpected situation, so you don’t have a pull cord/tag line, nor a clever tool like the Beal Escaper.)

Answer: the extended rappel.

Hopefully you don't find yourself doing this very often, but if it occasionally happens, this #CraftyRopeTrick could save the day. There are several variations on how to set this up. Here’s one.

Short version:

Instead of doing a standard rappel on both strands of the rope, you secure one strand to the anchor and make sure it’s absolutely long enough (here, 35 meters) to reach to the next anchor or to the ground.

Tie a rope block (knot or carabiner) on the short strand.

The long strand of the rope, which is 35 meters, reaches the lower anchor. The short strand of the rope (the pull side) is 25 meters long, and is hanging 10 meters above the lower anchor. Can you visualize this? Good!

The first person rappels single strand on the long side to the lower anchor.

The last person rappels single strand on the long strand, ideally on a Grigri so they can go hands free. They keep control of the short strand by clipping it to a quick draw on their harness.

When the last person reaches the end of the short strand, they start adding material (cordelettes, slings, etc.) to extend it. (“Extended” rappel, get it?)

Last person continues rappelling to the anchor. Retrieve by pulling the short side with your “extension” tied to it.

It's a tricky to take a decent photo of the rigging, so hopefully this diagram can help.

Conceptually this may sound pretty easy. In practice there are a lot of considerations to doing this efficiently and with the least risk.

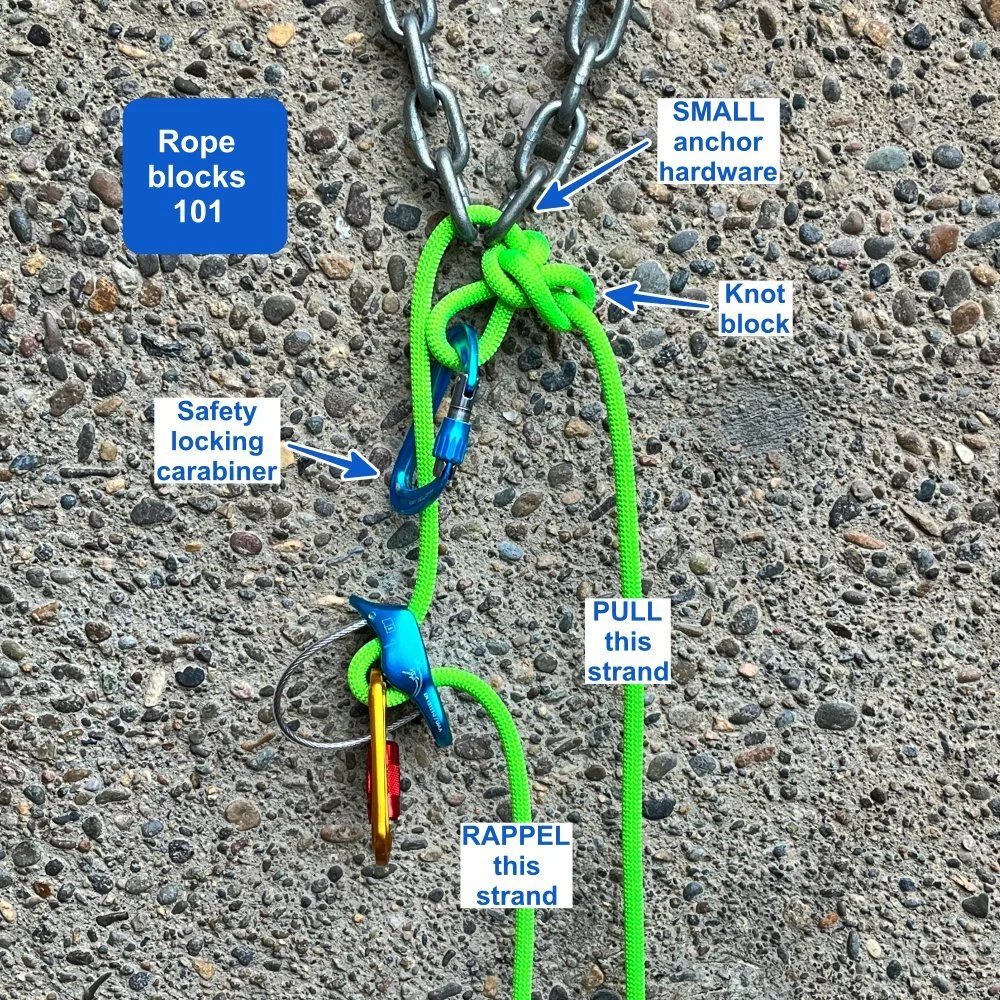

The primary safety concern is making a block in the rope that absolutely positively cannot pull through the anchor hardware. The best anchor hardware for doing a rope block is small chain links, or small to medium sized quick links. With this type of hardware it is pretty much impossible for the blocking knot to pull through. Keep reading for more discussion of rope blocks, and here's a longer article about them.

Here's a more detailed explanation of each important step.

When might you need to do an extended rappel?

The route was bolted for a 70 meter rope, and you brought a 60.

It's a climb you've never rappelled before and have no beta.

Maybe the beta is wrong.

Maybe the beta is correct if you use THAT anchor.

Maybe the anchor that people used to rap from is gone or was moved.

More extreme situation: Your rope got damaged near the end, you had to cut off some of it and now your rope is too short to make the standard rappel stations.

What's a big potential problem with the extended rappel?

If you begin to pull your rope, the end of the “real” rope goes up out of reach, and then the rope gets stuck. You’re now holding onto your “extension” as the only way to fix the problem. If you're on the ground, you can walk away and hopefully go get another rope and deal with it. If you are way off the deck on a multi pitch rappel, you could be in a serious situation.

What’s another option to descend?

The simplest and maybe least risky way to descend, if you have access to another rope and you're within one rope length of the ground: Tie off one end of the rope, toss it and be sure it reaches the ground, rappel, and come back and get it later with another rope. Plus, if you don't have enough extra slings/cord to extend the short side of the rope, then this approach is pretty much mandatory. Yes, it's a hassle and would kind of suck, but certainly better than the alternative.

What if you don't notice your rope is too short at the top, but only after you find yourself dangling on both strands, short of the anchor?

Yikes, scary! That definitely complicates things. There's no simple universal solution to this that I know about. You're probably gonna have to get resourceful - put some pro in a crack and build a temporary anchor, or clip into a bolt. Good reason for the first person down to carry some gear to do this.

What's the ideal terrain to try an extended rappel?

Best if the rock face is smooth, clean, and vertical with minimal chances of your rope hanging up.

Setting the correct rope length

There are a couple of ways to do this. 1) Lower the first climber 35 meters to the next anchor, or 2) Fix one strand from the end, have them rap on this, tie off the bottom end of the rope and then pull up the rope from above to set the correct length.

If you don't know the distance of the next rappel, you can lower your partner and keep an eye on the middle mark of the rope. If the middle mark passes through your anchor before your partner reaches the lower station, then your rope is too short.

If you’re lowering your partner, follow standard safety procedures such as closing the system by tying a knot in the end of the rope (assuming it's not tied to you) and use a third hand / autoblock backup.

If you lowered the first person down, they can stay tied in to the end of the rope to be sure that the last person does not rap off the end, and that one end of the rope is for sure at the lower anchor.

Extending the pull side

Before the first person heads down, they hand off all of their extra slings, cordelettes, etc. to the last climber. If both climbers have one cordelette of about 5 meters, there’s your 10 meter extension. This strand of the rope is not load bearing, you're only using it to pull down the long strand.

To connect slings to one another, girth hitch them together, no carabiner required. To connect a cordelette to the end of the short strand of rope, you can use a flat overhand bend. (This is another good reason to carry an “open” or untied cordelette, rather than one that's tied into a loop with a permanently welded double fisherman's knot.)

Rather than monkey around with extending multiple slings while you’re hanging in space, it's probably less risky and easier to connect all the slings you plan on using up at the top anchor before you start rappelling.

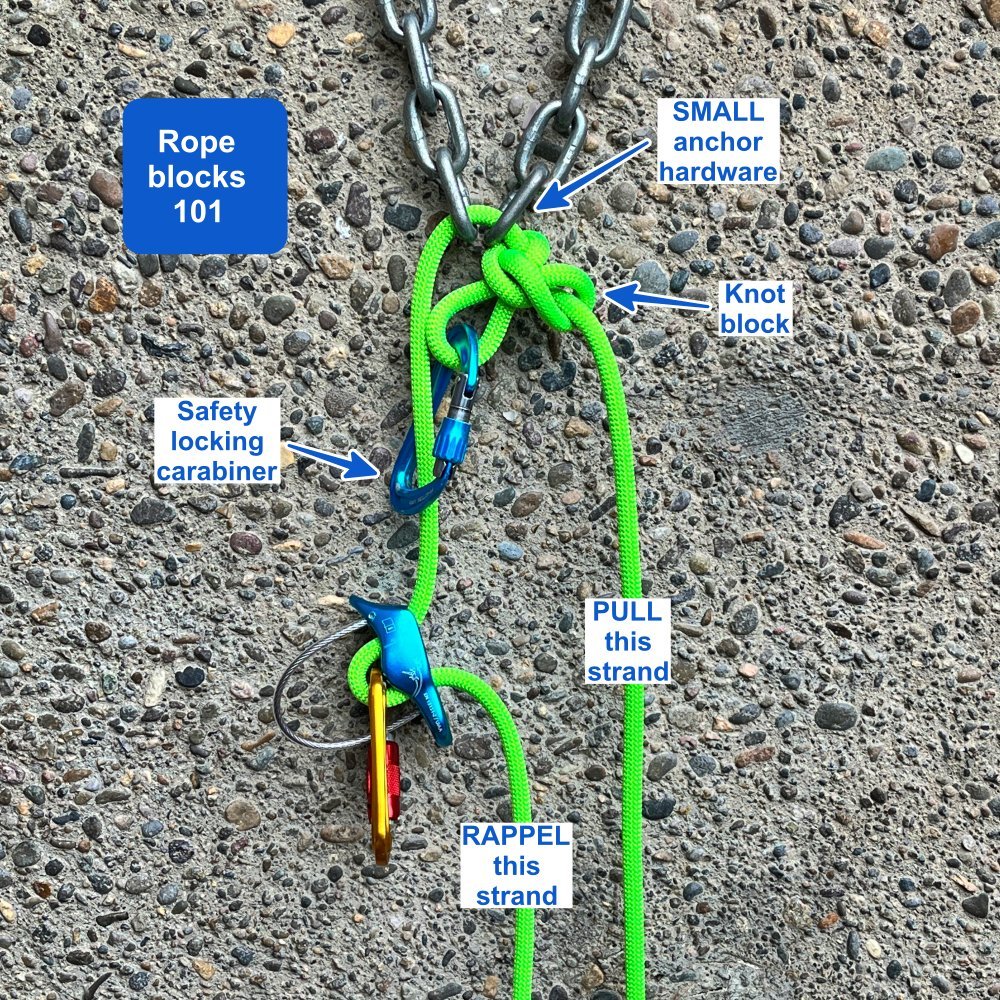

The extended rappel relies on a rope block. While conceptually simple, there are lots of factors to consider.

Detailed look at one way to set up a rope block.

The rope block

This extended rappel technique requires the skill and knowledge to use what's called a rope block. This goes by various names: knot block, carabiner block, static block, Reepschnur. This creates an obstruction on one strand of your rappel rope, that cannot be pulled through the anchor master point. The rope can slide freely in ONE direction, but not in the other.

The golden rule of the rope block is that the block absolutely cannot pull through the master point on the anchor. If it does, the person rappelling will probably die or your rope will get hopelessly stuck.

Typically a knot block is tied with butterfly or a figure eight on a bight. If you need a larger block, you can tie a well-dressed clove hitch around the spine of a locking carabiner, that works also.

This is an advanced technique, popular in the canyoneering world. Like many other things in climbing, if you screw it up you can die, so pay attention and absolutely practice on safe flat ground before you ever do this in the real world!!

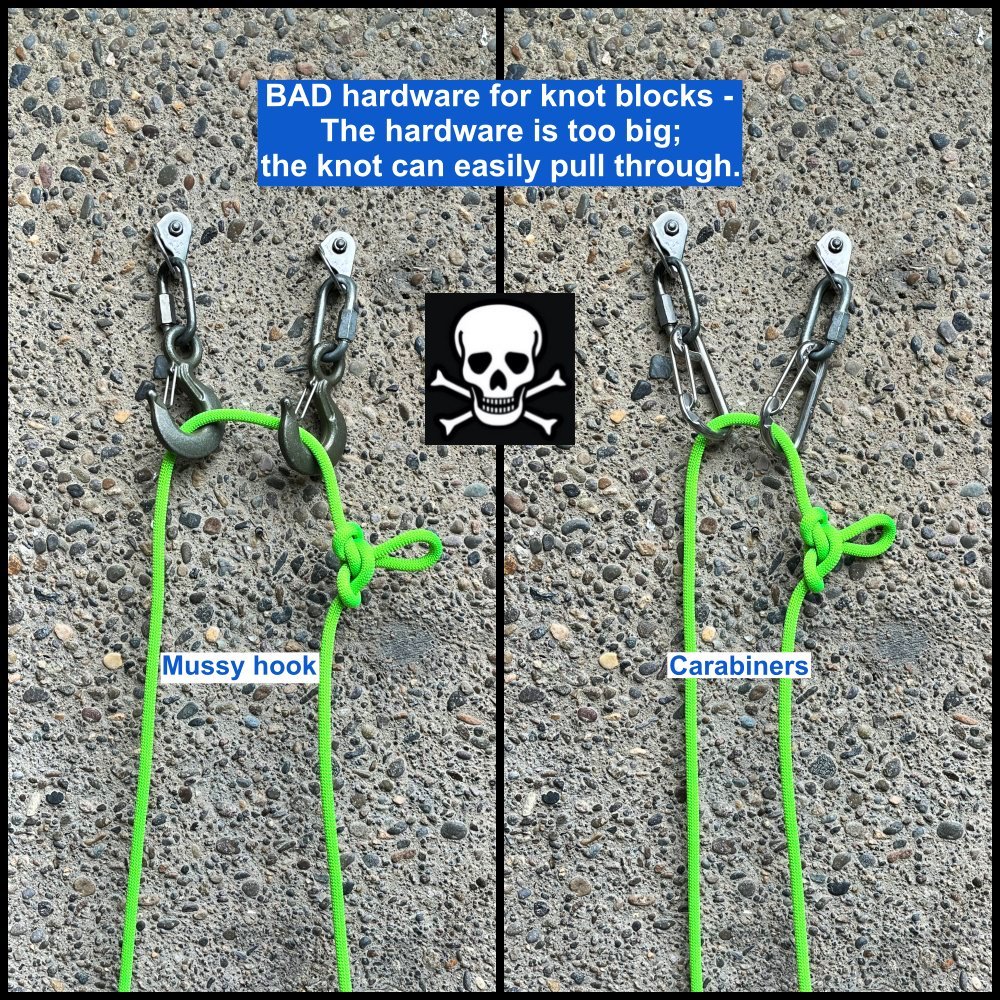

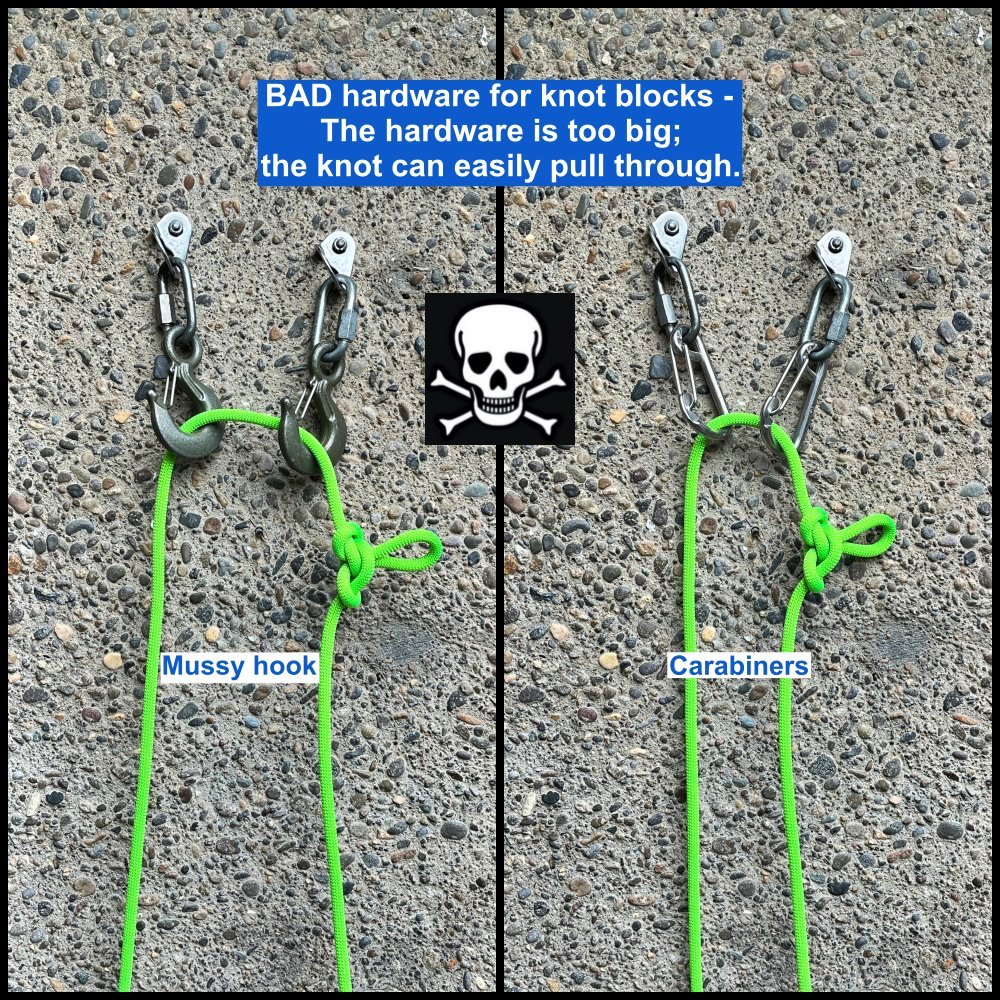

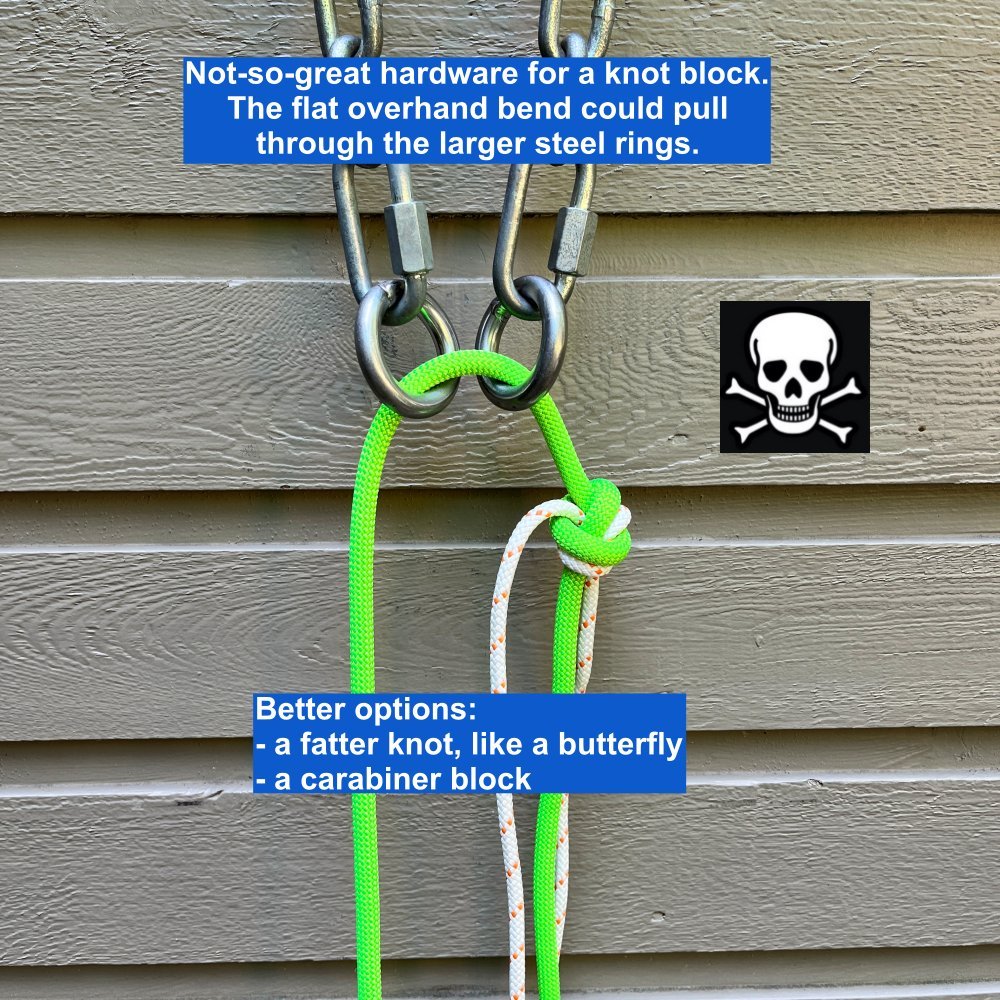

Anchor hardware concerns

This usually requires that the anchor master point is quite small, such as a chain link, quicklink, or a small bight knot tied in cord or webbing.

If you're rappelling through a carabiner or a large ring, the opening may be so large that a block may not work.

This is an excellent time to use a quick link on the master point, if you happen to have one.

Below: knot block on large diameter anchor hardware, don’t do this!

Rope blocks 101

A rope block (aka Reepschnur), is a technique where you block one strand of your rappel rope to prevent it from running through the anchor. This lets you do a single strand rappel on the other side. Conceptually it's pretty simple. In reality there are some nuances, and definitely some ways to lethally screw it up. Learn them here.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

This article was written with collaboration from Ben Wu, AMGA Certified Rock Guide. Connect with Ben at www.benwu.photography.

Rope block. Knot block. Carabiner block. Static block. Reepschnur.

They all mean pretty much the same thing: creating an obstruction on one strand of your rappel rope, that cannot be pulled through the anchor master point.

The rope can slide freely in ONE direction, but not in the other.

Doing this lets you rappel a single strand on the “fixed” strand of rope.

Main climbing application: it allows a retrievable single rope rappel; you carry less rope and weight.

To retrieve your rope, typically you use a lighter line such as a 6 mm pull cord (like the Petzl PURline) on the free running strand of rope.

Like everything in climbing, there are some definite pros and cons to this technique. If you’re considering using it, it's good to be aware of all of them. So let's get into it!

Conceptually, it's pretty simple. In practice:

There are some subtleties to doing it correctly.

There are some downsides to it even when you do it correctly.

If you screw it up, you could die or get your rope hopelessly stuck.

For these reasons, I personally consider it an advanced technique that you absolutely should practice with a qualified instructor. And, even when you’re confident with it, I feel it should generally not be part of your regular practice. It can definitely get you out of a jam in certain situations, but there are enough moving parts that I feel it's not a routine technique for most recreational climbing situations.

Here are articles on two closely related techniques that use rope blocks:

Not to dwell on the potential problems, but here are two reports of fatal accidents from rope blocks gone wrong:

First off, let's be clear on the Golden Rule of a rope block: it absolutely, positively cannot pull through the rappel hardware.

If you have not closed the system by attaching the pull side of the rope to the rappel side of the rope and the block pulls through the hardware, you will probably die.

If you have closed the system and the rope pulls through, your rope will probably be hopelessly stuck.

Take a close look at the anchor hardware and the diameter of your rope. If there is the slightest chance that you think the blocking knot could pull through the anchor hardware, then don’t use a knot block! (Consider a carabiner block instead, more on that below.)

There are really only a few times in recreational climbing when you might want to use a rope block.

You’re using a pull cord to do full length rappels. In this case, a rope block is pretty much mandatory. (Yes, there are some advanced ninja rope tricks like using a Stone hitch and a Fiddlestick to use a pull cord a different way, but we're not gonna get into that here.)

Your rope is too short to make the rappel. Lower your partner to the next station, make a rope block, and then extend” the “pull” side of the rope with whatever extra cordelette, slings, etc. until your DIY extension reaches the next anchor station.

There are two other situations where people often think they need a rope block, but there are other techniques you can use instead.

You damaged your rope and need to rappel. You rappel on the good half of the rope and use the damaged half of the rope with a knot block as a pull cord. To avoid doing this, you can do a counterbalanced rappel, read about it here.

If both partners have a Grigri, and you both need to rappel. It's pretty unlikely that both partners will have Grigris and not a tube device, but I suppose it could happen. You could use the counterbalanced rappel technique described just above. If one person has a Grigri and the other person has a tube style device, there are lots of other options for getting both people down without using a knot block, see some of them here and a photo example below.

Potential problems of a rope block (and pull cords)

The big one was already mentioned, but it's worth saying again: if the knot pulls through the hardware, the entire system fails and you die, or your rope gets stuck.

You’re adding an extra knot and carabiner to your system, which are two more things that can potentially get snagged when you're pulling your rope.

There are increased steps and complexity, which can increase the chances of making a mistake. This is especially true because for most people, this is a non-standard system that doesn’t get used regularly. See accident reports at the top of the page.

If you're using a lighter weight pull cord, if you pull your rope and it gets snagged after the end of the climbing rope is out of reach, you only have a pull cord in your hands to deal with the problem. Not good.

Maybe you forget what side to pull, whoops. It can be good practice to establish which side you block and which side you lower off of and do this pretty much all the time. For example. “L”=Left=Lower, and “R”=Right=Retrieve.

If you're doing multiple rappels, you can’t do the standard trick of feeding the pull strand through the bottom anchor and then pulling the rope. Why? Because you’re pulling the skinny cord, but the thick rope needs to be the one through the anchor. This means you have to re-rig the entire system at each rappel station, which takes additional time.

Yarding on a 6 mm rope can be rough on your hands. Consider adding a Tibloc or Micro Traxion on the pull cord to make the pulling easier. Gloves are recommended.

Pulling the rope can be significantly harder, because you do not have a counterbalanced weight on the pulling strand to assist your pull.

You’re rapping on a single strand of rope, which might be uncomfortably fast. Be sure you know some ways to add friction to your rappel.

If you keep the safety carabiner clipped when you pull, it can add a significant amount of extra friction, making your rope pull more difficult. This can be especially true on a low angle slab.

If you keep the safety carabiner clipped when you pull, sometimes the ropes can more easily twist together, which can cause your ropes to get stuck.

If you keep the safety carabiner clipped when you pull, you've essentially created a closed loop that you then need to pull down. If the two sides of the rope making this loop happen to go on either side of some rock spike, boulder, shrub, ice blob, etc., the loop is going to get caught when you pull down your rope, causing your rope to get stuck. This is probably difficult to visualize, so check out the photo below. (Yes, it’s a flower pot, but I think you get the idea . . . =^)

Rope block backups, pros and cons

It's good practice to backup a rope block by clipping the blocking knot onto the rappel strand with a locking carabiner. In the unlikely event of the block pulling through the hardware, this will save your life.

The backup stays in place for everyone except maybe the last person.

If the block is closely inspected after being fully loaded, and you are 150% sure that it cannot pull through the hardware, then the last person has the option of removing it. In many cases, this is a good idea.

Removing the block for the last person eliminates several of the problems mentioned above.

This is a call that the last person gets to make. (Like most everything in climbing, this is a subjective choice, and not a black and white rule.)

What’s the best anchor hardware for a rope block?

Small-medium size quick links, chains or small rappel rings are the most secure hardware for knot blocks. The openings are small and it's pretty much impossible for a blocking knot to be pulled through them.

Lots of people like to hate on carrying quick links, but this can be an outstanding time to use one. Keep in mind that a 5 mm, stainless steel, CE approved, 25 kN rated quicklink from CAMP costs about $6 and weighs just 22 grams. So weight, cost, and strength are not issues with carrying quick links, provided you get the right ones.

Some not-so-great hardware for a knot block would be a carabiner or Mussy hook. These have larger openings and greatly increase the chance of the knot pulling through. Remember, the knot will shrink as it’s loaded.

Nice diagram from the superb Petzl website. Small quicklink on the left, probably good. Large ring on the right, bad, the knot could pull through.

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Multi-pitch-rappelling-with-a-single-rope?ProductName=PUR-LINE-6-mm

What about a carabiner block?

Another option is to put a clove hitch onto a large HMS locking carabiner to serve as a block. This can work if the anchor hardware is something larger, like carabiners or maybe a Mussy hook. This is definitely an advanced technique that I recommend practicing with a qualified instructor.

Take extra attention to tie the clove hitch properly and dress it well. Test it when you're done by holding the carabiner with one hand and pulling hard on each strand of rope with the other. If the rope moves, you might have tied a Munter instead, and that is a Big Problem (photo below). If your rope is larger diameter (10+mm) or has an old crusty sheath, the clove hitch may not hold very well. This technique works best with newer ropes that are of standard climbing diameter around 9-ish mm.

A carabiner block looks something like this. Note that the block is backed up by a bight knot clipped with a locker onto the anchor, with a bit of slack in it. The slack shows that the carabiner block is properly behaving. The last person can remove the blue carabiner and untie the bight knot. Or, if they are feeling extra cautious, they could clip the blue carabiner onto the left strand of rope as a back up. Again, this adds more hardware that can get hung up when you pull your rope, so it's a trade-off.

Is it OK to load a carabiner like this? Yes, it’s fine. You are not putting any two or three way loading on the carabiner. It’s holding body weight only, and there's no way the carabiner will be damaged rigged like this.

With a carabiner block, be SURE you tie a clove hitch and not a Munter hitch!

What knot should I use for the block?

An overhand on a bight, figure 8 on a bight or a butterfly can all work as a knot block. In these examples I’m using a butterfly. Be aware that all knots will tighten under load and become smaller. Remember the Golden Rule: if you think there’s the slightest chance of the knot pulling through the hardware, then don't do it!

A flat overhand bend (formally known as the “EDK”) can work, depending on the diameter of your rope, and if you're using small anchor hardware, like chain links.

An overhand on a bight is slightly smaller profile than the figurine or butterfly. This could be a good thing as it's less likely to snag one pulling down your rope, or it could be not so great if there's a slight chance of getting pulled into your hardware. Pros and cons to everything . . .

Will the blocking carabiner get damaged when I pull the rope?

Probably not.

Some people seem to be concerned that the carabiner clipped to the blocking knot is somehow going to fall and maybe be damaged when you pull the rope. Why does this not happen?

With any rappel much less than the full length of the rope, the carabiner will be pulled to the lower anchor and be in your hand before the other half of the rope even starts to fall down.

However, it may bounce around a bit on the rock and get dinged up on the way down. If this concerns you, you can use an older carabiner or a steel quick link. Or, if you have complete confidence in the knot and the anchor hardware, you can remove the backup carabiner for the last person.

What about rapping with a Grigri, don't I have to use a block to do that?

Nope. There are lots of different ways to rappel with a Grigri that don’t require a block. I have a whole article about this, read it here. Below is a photo that shows one of several simple methods.

If one person on your team has an ATC, you can simply tie off one strand of the rope for everybody with a Grigri, have them go down on one strand and then the last person unties that knot and rappels normally on two strands.

There you have it: my thoughts on the pros and cons of rope blocks.

Under ideal circumstances with proper anchor hardware, they can work pretty well. But as you can see there are a lot of subtleties to doing it correctly. Once again: I consider this an advanced technique that I highly recommend you practice in a controlled environment with a qualified instructor before you ever try it in the wild. Choose wisely, my friends.

The "hybrid quickdraw"

Did you intend to go trad climbing but changed your mind to clip bolts? Here's a way to change those floppy alpine draws into easy-to-clip “hybrid” quickdraws”.

This #CraftyRopeTrick comes from AMGA Certified Rock Guide Adam Fleming. Connect with Adam on Instagram: adam.fleming.climbs

Here's how to turn that 60 cm or even 120 cm sling into a sport draw.

Did you intend to go trad climbing, but changed your mind to try some sport routes?

Are you on a long multi pitch route that has a mix of bolts and trad gear?

If the sport climbing is at your limit, it can be pretty annoying to try to clip that bottom carabiner that always seems to be flipping around and facing the wrong direction. And you probably don't want to take a whole separate rack of sport draws just for the bolted part.

Here's a simple trick to help solve this.

Take a 60 cm sling, double it, then make a girth hitch onto the bottom carabiner. This locks the sling in place, similar to a sport quickdraw, and makes it much easier to clip. Adam call this the'“hybrid quickdraw”.

Check out a short video Adam made about this on his Instagram.

Hair /clothing caught in rappel device - whaddya do?!

Did you catch your clothing or even your hair in your rappel device? Ouch! This is fairly common, but it's also easy to fix if you know how. One more reason to carry a friction hitch or two and an extra sling.

You're midway down your rappel and whoops, your clothing / hair / packstrap / whatever gets caught in your rappel device. (This is actually a fairly common problem, and it’s happened to some of the best climbers.)

What do you do?

Fortunately the solution is pretty easy. Here's one approach.

Stop your rappel. You are using a third hand back up under your device, right? So push this up the rope as far as you can, and let it take your weight. If you don’ t have a third hand, you can use the classic method of wrapping the brake strand of the rope several times around one leg.

Tie a Klemheist hitch (as a foot loop) on the rope above your device. This is a great place for a cordelette if you have one. Use what you have. A short friction hitch loop with a girth hitched 120 cm sling works fine as well. Get resourceful. A klemheist will probably be better than a prusik because a) you can use any material you have to tie it, b) you can tie faster (maybe even without looking) and c) it can be a little bit sloppy and still hold.

Put 1 foot into your new foot loop and stand up. Now, your weight should be on the friction hitch / footloop and off of your device. Remove hair or clothing, and be sure the rope is properly installed in your rappel device.

Remove the foot loop hitch and continue rappelling.

Notes . . .

You may be tempted to get out your knife and try to cut away the problem. Yo, be careful! Sharp knives and ropes under tension can be a very bad combination, so it's probably better to try the method above before you use an open blade. If you have a small knife with scissors, that could be a slightly less risky option. See Instagram video below of somebody actually doing this!

Practice this with an old T-shirt, wig, Barbie doll, shoelace whatever, in a controlled environment, very close to the ground.

Of course, it's great to try to prevent this problem before it ever happens. Tuck away loose clothing and hair before you start rappelling, use a hair tie, and take extra caution if it's a windy day.

In the photo below on the left, I have a Dyneema sling girth hitched onto a Sterling Hollow Block. It's worth pointing out that Sterling recommends that you not do this. Personally, because this is only holding your body weight for a couple of seconds, I’m comfortable with it. But, if you want to follow manufacturer recommendations, connect the two with the carabiner to get full strength.

Two ways to make a friction hitch foot loop. Short friction hitch and 120 cm sling on the left, cordelette on the right.

Here's a real life Instagram selfie video of a guy cutting his hair with a knife! Hopefully, after reading this far, you’ll never have to do this!

All so you don't turn out like this person!

(image: @caiocomix

Anchor forces from lowering

Say you’re lowering your partner from a top rope anchor, with the rope running through one carabiner. As your partner descends, what's the load on the anchor? Is it your partner’s bodyweight, 2x their bodyweight, or something else?

The illustrations in this article (shared with permission) come from the excellent website RopeLab, run by Australian rigging expert Richard Delaney. RopeLab has a ton of great material for anyone who wants to dive into ropes, rigging, and mechanical advantage, check it out! There's a fair amount of quality free information, but getting an annual subscription unlocks the entire website. You can also connect with Richard on Instagram and his YouTube channel, where he has loads of concise, informative videos.

These diagrams come from a RopeLab online mechanical advantage quiz, which you can find here.

You’re top rope climbing with your partner. They’re climbing, and you’re on the ground belaying. The rope goes from your harness, up to the anchor master point, and then back down to your partner.

In this common configuration, the load on the anchor can change depending on:

who is holding the rope

if the climber is resting and not being lowered

if the climber is being lowered, through typically a carabiner or two

For example:

Your partner finishes the climb, and calls for take and lower. You lock off your belay device, they lean back, weighting the rope, and you lower them to the ground.

What’s the force on the anchor when you're lowering them? Many people think it has to be twice the weight of the climber. Say the climber weighs 100 kg. You, the belayer, need to counterbalance that force with 100 kg of your own. So that means a 200 kg load on the anchor, right?

Well, turns out it's not quite that simple. Let's look at a few examples to see how this works!

Question 1 - A person (weight 1 kN) is holding their own weight, on a rope that goes through a 90% efficient pulley on an overhead anchor. What is the theoretical force on Anchor A?

IMAGE: ROPELAB.COM.AU

Answer: 1.0 kN

If you’re statically holding your own weight like the diagram, the anchor sees the force of your body weight. It doesn't matter if it goes through a 10% efficient pulley or 50% efficient carabiner, the force on the anchor is going to be the same.

(To add another interesting variable to this, if there's any sort of ledge or friction between you and the anchor, that will further reduce load on the anchor. But for now let's assume the climber is free hanging.)

Question 2 - A climber (weight 1 kN) is LOWERED with the rope running through a 90% efficient pulley. What’s the theoretical (including friction) force on Anchor B?

IMAGE: ROPELAB.COM.AU

Answer: 1.9 kN

The anchor sees the force of the climber, plus the force of the belayer to hold the rope, minus the 10% friction at the pulley. So, the force on the anchor is not two times the weight of the climber. (Yes, top roping through a pulley doesn’t happen in climbing very often, and it can actually be a bad idea if your belayer weighs much less than you do, but we’re using it here as an example.)

Question 3 - A climber (weight 1 kN) is LOWERED with the rope running through a 50% efficient carabiner. What’s the theoretical (including friction) force on Anchor C?

IMAGE: ROPELAB.COM.AU

Answer: 1.5 kN

When lowering, the anchor sees the force of the climber, plus the force of the belayer to hold the rope, MINUS the 50% friction at the carabiner. The friction from the carabiner significantly reduces the load on the anchor. This is why a belayer who’s a lot lighter than their partner (usually) doesn’t get lifted off the ground when they lower their partner from a toprope.

Here's another way to think about it:

When you’re raising something, friction can be your enemy.

When you're lowering something, friction can be your friend.

Here, friction at the anchor reduces the load on the anchor AND transfers less weight to the belayer for them to manage. That’s a good thing!

What are some practical uses for this in the real climbing world?

Rappelling, and lowering yourself, put the same load onto the anchor. If you top out on a 1 pitch climb and find yourself at an anchor you think is sketchy, rappelling might be less risky than being lowered.

Being lowered by your partner will always put more force on the anchor then rappelling or lowering yourself.

Any additional friction in the system, such as the rope running over rocks or ledges, will further decrease force on the anchor.

Top roping through a pulley increases load on the anchor, and can make it more difficult to catch a fall because of the reduced fraction. Don't do this.

It's easy to test systems like this yourself. Just get a barbell plate of a standard amount (a round number like 10 lbs/kg helps) and an inexpensive digital scale like the one below. This scale is about $10.

Rack spare carabiners in a "football"

Big wall climbers need a LOT of spare carabiners. Here's a good way to keep them tidy - rack seven of ‘em together. (Like the 7 points for a touchdown in ‘Merican football, eh?)

I think I first heard of this tip from big wall ace Pete Zabrok. Pete wrote a great book on big wall climbing called Hooking Up, highly recommended!

Here's one way to help tame the entropy of your big wall gear harness.

Aid climbers need a LOT of free carabiners. Here's one good way to carry them.

Rack seven carabiners together. One to your gear loop, and then three more pairs hanging below that. This keeps them fairly compact and tidy. Seven, like the points for a touchdown in American football, eh?

Are you concerned that your fumbly fingers might accidentally unclip the top carabiner and then you lose all seven? An Instagram friend suggested racking 6 carabiners / 3 pairs, and making the top two opposite and opposed. This makes it less likely that he might accidentally unclip the whole thing. I think this is a pretty clever idea. So there you go, do it with six or seven, your choice!

How to extend a quickdraw

Are you trying some super-steep sport route? Extending the quickdraws might make clipping easier. Here are two good ways (and two not-so-good ways) to do this.

If you're on some ultra-steep or reachy sport route that requires extended quickdraws, here are some ways to do it. And a couple of ways not to.

In addition to connecting quickdraws like this, you could also use a 60 or 120 cm sling.

Two good methods to extend a quickdraw:

Probably the easiest: remove the top carabiner from a second draw, and then clip the dog bone into the bottom of the first draw (left).

A more secure version: replace the carabiner with a quick link or locking carabiner (right).

Two not-great ways to extend a quickdraw:

Chaining together two non-locking carabiners is a no no. A fall could twist the carabiners together and cause them to unclip (left). It is okay to clip the bottom carabiner for a rest, and then clip the rope through the top draw when you continue climbing.

The quickdraws are extended correctly, but the rope is clipped to the wrong place. A fall with the rope clipped like this might damage the dogbone of the lower quickdraw (right)

My favorite mini headlamp - the Petzl Bindi

Headlamp technology keeps getting more ridiculously amazing, with lighter weight, brighter bulbs, and better design. While for climbing having something with 500 or more lumen output is really nice, there's also a place in your pack (and around the house) for a headlamp with more modest specs and lower cost. My new favorite: the Petzl Bindi.

Full disclosure: Petzl sent me this for free. It replaces a Bindi that I bought that decided to go for a walk. That in no way biases my review; it's a cool product and I want to tell you about it. There are paid product promotions on Alpinesavvy. In the rare cases when I get a free product like this, I’ll always let you know.

Modern headlamp technology is ridiculously awesome, and there's basically zero excuses to not have one as part of your everyday carry kit at pretty much all times.

Petzl and Black Diamond have been duking it out in the headlamp arena for a very long time, and we, the lucky customers, benefit.

For mountaineering, or longer trips in colder weather, you probably want a headlamp with a larger battery and a minimum 500 lumens, like the Petzl IKO Core, or the 900(!) lumen Petzl Swift. But for more general purpose hiking, 10 essentials, dog walking, everyday carry type stuff, a headlamp that's lighter, less expensive, with less light output works just fine - like the Petzl Bindi.

Here's why the Petzl Bindi is my favorite mini headlamp:

A ridiculously light 35 grams.

Minimalist elastic cord headband, yet still comfortable and functional.

Three main light levels: low, medium, and high (high is 200 lumens).

Red light for maintaining night vision and not blinding your friends.

Flashing red strobe light for increased visibility (and signaling, I suppose).

Rechargeable battery via micro USB port. (Yes USB C would prolly be better . . .)

Battery indicator light flashes for a few seconds after you turn it off to show the approximate battery level, very handy.

Reasonably weatherproof for hiking in the rain, but not for scuba diving.

Two different ways to lock the switch so you avoid accidentally turning it on in your pack.

Superbly engineered gear, at a fair price of around $45. I think that this (or something like it) belongs in the pack of just about everybody pretty much all the time.

Another option from Petzl that's even lighter and less expensive, but with a lot lower light output, is the e+LITE. (Personally, I like to have the option of the 200 lumens when I need it, so the Bindi recently replaced my much older eLITE.)

Reminder, there are no paid product promotion or affiliate marketing links on our Alpinesavvy. I occasionally share gear that I think is great, and there's no financial benefit to me when I do so.

Rappel anchors - replace crap webbing

It's common to find a mess of cord and webbing at some alpine rappel anchors. Do yourself and everybody else a favor: cut away everything that's questionable and add some new material of your own to make an anchor that's more reliable and easier for others to inspect. Watch the video for a scary moment of what can happen if you don't!

image credit: Silas Rossi, @silasrossi

Yikes, what a mess! It's very hard to evaluate something like this. Take some time to cut out the junk and add your own good quality cord.

Check out this YouTube short video from IFMGA certified guide Karsten Delap. (Yes, the webbing is tied directly through the bolt hangers, which is not standard practice, but still should not be direct cause for failure.)

Double fatality at Tahquitz Rock, CA, Sept 2022

When rappelling, both climbers apparently clipped in to a single loop of old tied webbing. The webbing broke. Both climbers fell and died. (It was raining, so perhaps the webbing was wet and harder to inspect or notice that it was old. The webbing was tested post-accident to only 2-3 kN. ) Here’s the accident report from the SAR team, well worth reading.

Sadly, I could go on, but I think you get the idea.

Webbing or cord on existing anchors is guilty until proven innocent! Always inspect it before you use it!

Cord and webbing used in climbing is very strong and reliable when it’s new and tied correctly. But when it’s been in place for a while, subject to ultraviolet light, mountain weather, possible rockfall, and maybe nibbling by rock rodents, it can be dramatically compromised.

A big rat’s nest of cord, with multiple slings ranging in age and quality, is hard to evaluate and potentially dangerous.

Instead of adding one more piece of your own cord to the mess, do everybody a favor: cut out all the junk and leave just two or maybe three good quality pieces.

Especially for more adventure climbing or alpine routes where you’re away from properly bolted anchors, it's good practice to bring some extra cord or webbing (and ideally a knife) that you can leave behind, so you know there's at least one good sling for your descent.

My personal rule: I really try to avoid rapping off of a single piece of cord unless it’s something brand new that I just tied myself. Any single cord that I find gets a back up. (That might be a little conservative for some people, but we are all accountable for our own level of acceptable risk.)

This is a fine reason to carry a cordelette. It's inexpensive and easy to cut up to leave behind when needed.

Recycle your old cordelette. If you climb a lot, you probably wanna retire your lead cordelette from regular anchor duty after about a year. Great, you now have some material for emergency anchors. Keep the old one in the bottom of your pack for that purpose.

So, how bad is old webbing?

Short answer: it can be horrendously bad. My buddy Ryan Jenks at HowNOT2 tested some ancient sun bleached tubular webbing that was out in the elements for many years. It broke at about 3 1/2 kN! You could generate this with a decent bounce test when you're setting up a rappel!

Compare this to New 1 inch webbing which is about 18 kN, and 7 mm cord, which is about 13 kN.

Here's my cheap hardware store checkout line lock blade knife that I've had for like 20 years. It's taped securely shut so it can never accidentally open. It doesn't need to be fancy. It's been used countless times to clean up nasty rappel anchors.

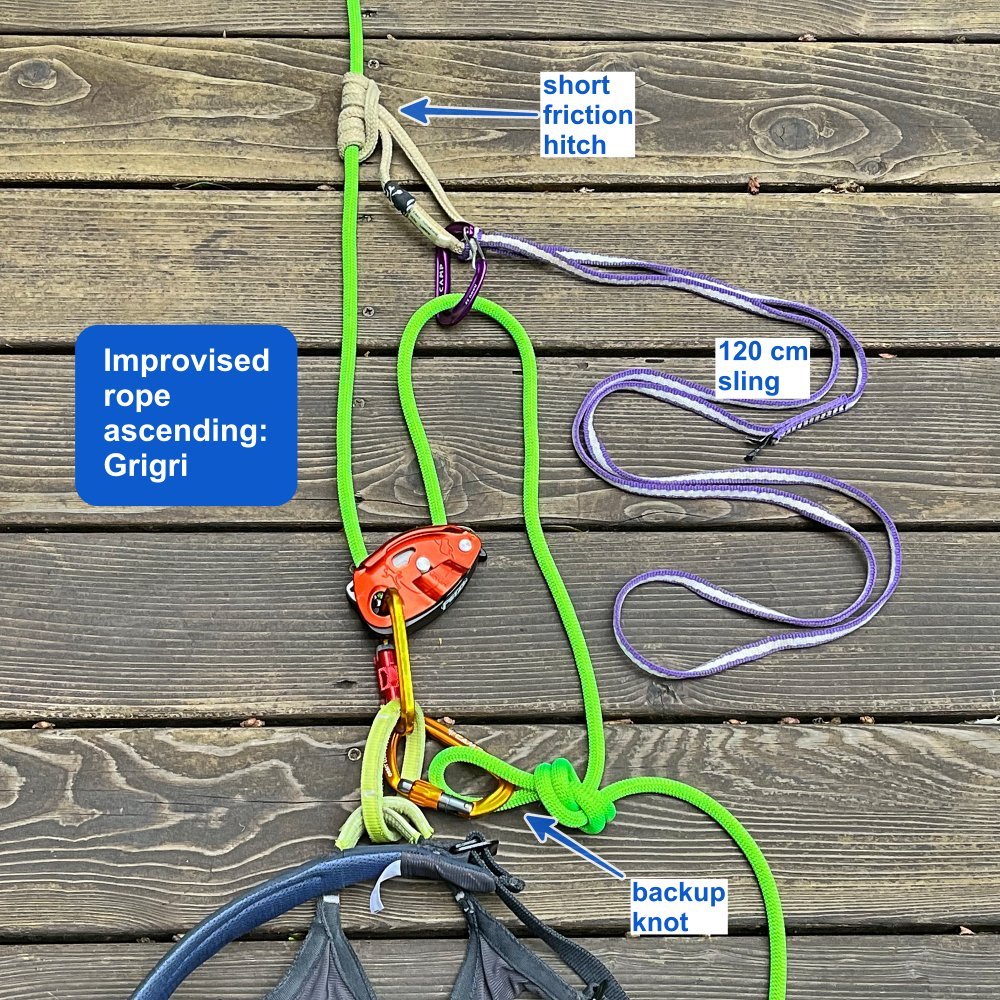

Rope ascending with a Grigri and belay device

Do you need to do some improvised rope ascending? You don't need a designated waist and foot prusik cord. Instead, be resourceful with the gear you probably already have. All you need is a friction hitch, long sling, and a modern belay device like a Grigri or “guide-mode” style belay device.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

Hopefully you don't need to do this very often, but knowing some ways to ascend a rope without specialized gear (like handled ascenders and aid ladders) can be a useful self rescue skill. Why might you need to do this?

Stuck rappel rope (need to ascend it and fix the problem, yikes!)

Rappel down too far and miss your next anchor

Fall on an overhang or traverse, and are hanging in space or in unclimbable terrain

Can't make the moves and need to do some rope climbing to get past the hard part

Go up the rope to deal with an injured/scared partner

The old-school method was using some kind of dedicated foot and waist prusik loops. These can work, but they have some problems. It can be very slow and awkward, they are prone to tangling on your harness, and it's a specialized piece of rescue gear that you may always carry with you but never use. My opinion: in most cases, don't bother carrying them at all.

Another approach to rope ascending: creative use of gear you probably already have with you. With just this gear, you can get up a rope:

Grigri (or plaquette style belay device like an ATC Guide)

a short friction hitch

a double length / 120 cm sling

If you have some more modern tools, such as a Petzl Tibloc, Micro Traxion or Rollclip carabiner/pulley combo, this procedure becomes quite a bit easier. But for now let's see how to do it with the bare minimum of gear, okay?

A few notes:

The basic way this works: tuck your foot under your butt, stand in the foot loop to create slack, and then pull the created slack through the belay device.

Rigged like this, you have some mechanical advantage. It's not much, because of the friction every time the rope changes direction. Don't think you can do one arm pull ups and get yourself of the rope, you gotta use your legs. See the first point: stand up, create slack, pull slack through the device.

Interesting side question, what is the mechanical advantage here? Is it a 2:1 with a redirect, or is it a 3:1 because you’re lifting yourself? Well, there are some pretty smart people that feel pretty strongly one way or the other, but I'm gonna roll with rigging expert Richard Delaney from RopeLab. Richard says this is a 3:1. There are three strands of rope supporting the climber’s weight. For you to move up the rope 1 meter, you need to pull 3 meters of rope through the system. Yes, this may hard to get your head around, it was for me! Here's an article from moi and video from Richard explaining how this works.

Typically you're going to have less unwanted friction if you use a Grigri. This can depend on a rope diameter and whether the sheath is slick and new or old and crusty. If you have a Grigri, try that first.

If it's fairly low angle, you may not need the foot loop. Use the friction hitch as a handhold, lean forward, pull up with your arm, and pull slack through the device.

With the foot loop, it can help to take an extra wrap of the sling around your foot. This holds your foot in the sling so it doesn't slide out.

If the angle is quite steep, you may find it easier to clip a redirect carabiner into the friction hitch and clip the tail of the rope through the carabiner. That's what I show in the photos. This allows you to pull DOWN on the rope rather than UP, which can be more ergonomic if you're doing it for a while.

When ascending a rope, it's best practice to be connected to the rope in two places. My preference: every 6 meters or so, tie a backup bight knot in the rope below you, and clip it to your harness. You could also attach another sling from your harness to the foot prusik, but I find that to be annoying and tangle prone.

Think of rope ascending as a “movement sandwich.“ That’s a short movement of exertion, in between two periods of rest. Rest > move > rest. Rest > move > rest. Tuck your foot under your butt before standing, and use your legs. If your arms are getting pumped, you’re probably doing something wrong.

If it's vertical or overhanging, it may be more efficient to add a second foot loop with another 120 cm sling. This lets you push up with both your legs and can help save energy. On lower angle rock, it's not required.

Example 1: Improvised rope ascending with a Grigri

Sequence:

Set it up as shown below. Be sure the rope is loaded correctly in your Grigri.

Sit back in your Grigri. This is the “rest” position.

Slide the friction hitch as far up the rope as you can.

Put your foot in the purple sling, tuck your foot under your butt (important!), stand up, and pull the slack you created through the Grigri. Sit back down to weight the Grigri and rest for a moment.

Repeat. Tie overhand backup knots and clip to harness whenever you’re getting scared. =^)

Example 2: Improvised rope ascending with a plaquette style belay device

Same sequence as above. Be sure you set up the rope correctly through your belay device, as shown below.

Sit back in your belay device. This is the rest position.

Slide the friction hitch as far up the rope as you can.

Put your foot in the sling, tuck your foot under your butt, stand up, and pull the slack you created through the rappel device. Sit back down to weight the device and rest for a moment.

Repeat. Tie overhand backup knots and clip to harness as needed.

Finally, here's a quick demonstration from IFMGA certified guide Karsten Delap, getting it done with a Grigri and a Tibloc.

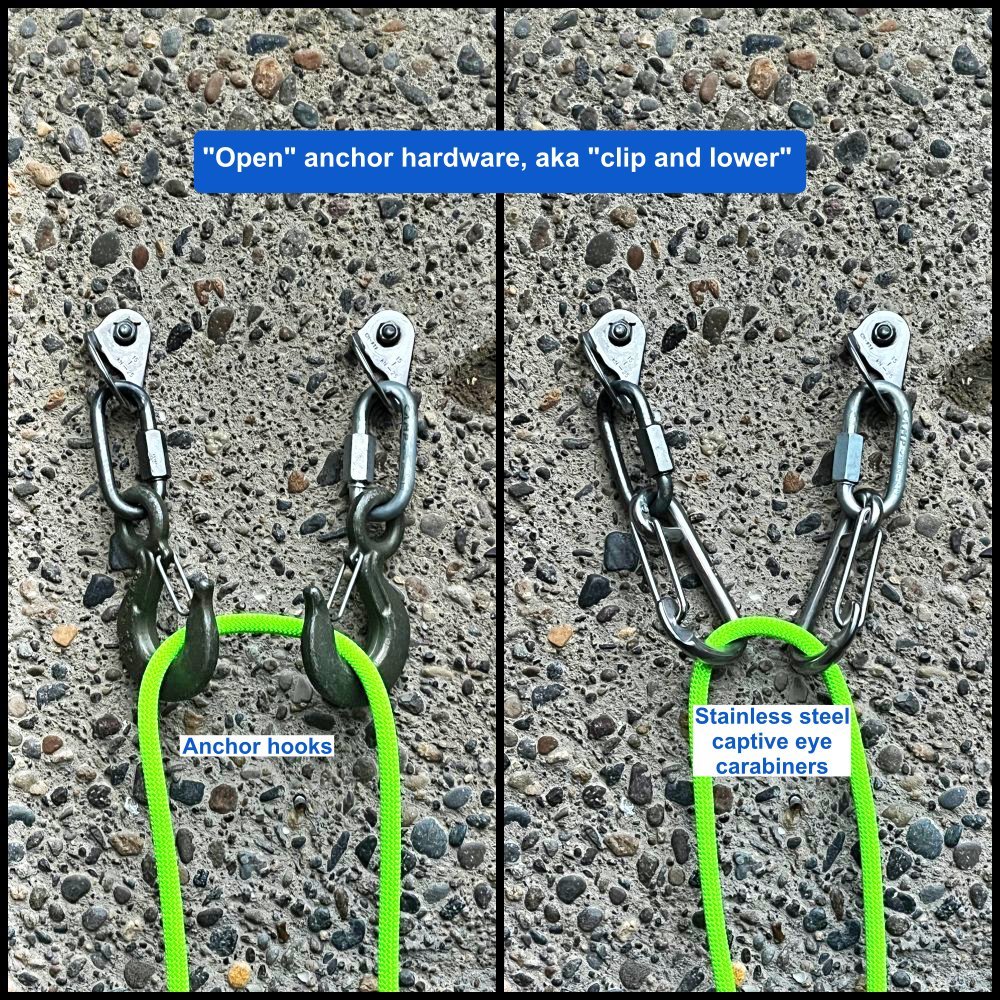

Anchor hardware systems: "closed" vs. "open"

Anchors with a “closed” metal chain or ring at the bottom require MANY steps when transitioning to a lower or rappel. For single pitch routes, “open” anchor hardware like a hook or carabiner lets the last person to simply clip and lower off; more efficient and lower risk. See some examples, and learn why a major American climbing organization favors the open anchor.

Traditional anchor hardware, at least in most parts of North America, has typically been some combination of chain links, quick links, and/or welded rings.

One term for these is a “closed” hardware system, because the bottom link (where the rope needs to go for you to rappel or be lowered) is closed.

Examples of CLOSED anchor hardware:

Quicklinks with chains

Quicklinks with rings

Fixe vertical anchor. These are great for multi pitch climbs, but not necessarily for single pitch routes. Strong though it is, when that big ring at the bottom wears out the entire anchor may need to be replaced.

However, for single pitch routes, an increasingly popular anchor is an “open” hardware system, also known as a “clip & lower”.

Examples of OPEN anchor hardware:

Anchor (aka “Mussy”) hooks.

“Captive eye” carabiners, which are theft proof (unless you’re a scumbag with pliers.) Many rock gyms have these on all the perma-draws. Those are galvanized steel for indoor use. Stainless steel is strongly preferred for outdoors.

To be clear: generally, it’s best practice with any kind of anchor hardware, closed or open, to toprope on YOUR gear and use the hardware to lower off only for the LAST person. More on that below.

Because the anchor points are “open”, and often facing away from the rock, it is remotely possible to unclip the rope if you were to climb above them and fall at some weird angle. It appears that this was a factor in a tragic accident in the United States in 2023; more on that below. If you stay below the anchor and put a steady load on it as you would when lowering, it should not be a problem.

The best use of open hardware: lowering off one pitch routes. A multi pitch route, closed hardware is preferred, because you were only attaching to the anchor or rappelling down. To rappel you need one end of the rope available, which you thread through the anchor and pull rather than clipping. So, there's no reason for open hardware on a multi pitch.

Note the anchor hooks and carabiners both face outward, not opposite and opposed. There’s a reason for this, more on that below.

Close up of stainless steel captive eye carabiners. About $6 each. Not CE rated, but 3/8 inch / 10 mm marine grade stainless steel, with a breaking load of nearly 5,000 pounds / 2,250 kG. That’s #SuperGoodEnough for a lower off anchor! These particular ones have gates that are quite stiff, which makes accidental backclipping much harder. That’s good!

I got these from usstainless.com.

Ram’s horn / pigtail open anchors

Another style of open anchor hardware is a “ram’s horn”, aka pigtail. More common in Europe, but still quite rare in the United States. They are being used in a few areas, so I thought I’d mention it.

These are typically made from 10 of 12 mm stainless steel rod, and cost about $10 each. They also come in titanium, which wears out faster than stainless steel, but is good for coastal areas. And no, it doesn't twist your rope.

You can get them from team-tough in the US or in Europe from bolt-products. (Reminder: there are no affiliate marketing links on my website. I post links like this as a convenience.)

Simply flip the rope and around each horn and lower off. Does it look sketchy to you? Could the rope magically unclip itself from both horns at once? Pretty much impossible; it’s close to getting-hit-by-lightning unlikely.

Apparently in Europe it's quite common to have just a single horn to lower from, but personally I'm not too excited about that. Here's an accident report from the Austrian Alpine Club about this failing during a rappel, which I'm pretty sure was from just a single point, and not two separate pigtails. The club mentions there have been several accidents related to these but I don't know any other details. Remember, Americans like moi prefer redundant anchor points.

Again, the best use of these is LOWERING from single pitch routes, not as rappel anchors. (Using these doesn’t make much sense to me on multi pitch rappel anchors, because you're already untied from the end of the rope, so a closed ring seems lots more secure.)

From the article:

“After a few serious climbing accidents, we (Austrian Alpine Club) have to advise against using pig tails (see picture) for abseiling. In the event of jerky loading and unloading, the rope can detach completely from the steel bracket!”

Here's another accident report from Austria, not sure if it covers the same incident or not. It's in German.

“The sow tail, which is designed as a deflection hook, is a system that is open at the top and requires correct insertion of the rope as well as the subsequent downward load. If the rope is moved up over the sow tail, it can be unhooked. This danger must be taken into account, especially if the belay with pigtail is positioned below the climber's tie-in point.”

Note the photo below where these are used as a pair. This makes it more secure than just a single one.

image: https://climbingboltsupplies.com/products/bolt-products-rams-horn

Here's an outstanding video from our friends at HowNot2.com showing different ways to rig anchor hooks, some potential problems, and lots more. A good instructional segment starts at 8:30.

Check out this YouTube video by Bobby Hutton (part of the team at HowNot2.com) for more on the ram’s horn. Note in this video he has a very interesting vertical arrangement to the anchor points, rather than two horizontal components. Check the video to learn the benefits of this system.

OK, got it. So what? What’s cool about open hardware for single pitch routes?

My buddy Ryan Jenks at HowNot2.com has a great blog post on this, so I'm gonna borrow a few paragraphs from him (used with permission, of course.)

“Closed systems require climbers to untie their tie-in knot to connect the rope to the anchor to clean a route. This can be dangerous if a climber misses a step or gets confused. Speaking of steps, closed systems require a lot of them. Cleaning a route with a closed system anchor demand knowledge, focus, memory, and organization. Missing any step can be catastrophic. Closed systems make it impossible for the rope to come out of the anchor, this is their main benefit.

Open systems require less knowledge and memory because they remove at least 8 steps when cleaning a route. We think that makes them safer. Open systems also ease traffic jams on popular routes because it is much faster to clean them. The disadvantage of open systems is that it's not impossible for the rope to come out, it's only extremely freakishly unlikely.”

Ryan also put together this great spreadsheet/list on his blog post of comparing the steps involved with different systems. Hint, fewer steps are usually better!

image: https://www.hownot2.com/post/mussy-hooks

Let's talk about anchor hooks, the most common flavor of open anchor.

Below is a photo of some hooks recently retired from one of the most popular single pitch routes probably in all of the United States, “5 Gallon Buckets” at Smith Rock Oregon. Yikes, those look pretty scary, don't they? (Sidenote, I‘ve lowered off these exact same hooks.)

I'm using the term “anchor hooks”, because that’s preferred by the American Safe Climbing Association, rather than “Mussy”. See their comments on this below.

Here's why anchor hooks are great.

They cost about $9 each.

They’re attached with a simple quick link to the bolt hanger, so the bolt never needs to be touched. Just open the quick link and put in a new hook. Fast and easy to replace.

Even these worn out hooks both break tested over 60 kN!

Very long lasting. I have no idea how many thousands of people have lowered off these hooks, but they lasted for many seasons on a very popular route.

Side note: Anchor hooks are typically placed so both gates are facing OUT from the rock. Yes, this means they are not opposite and opposed. Why? See next paragraph.

photo credit: https://www.mountainproject.com/photo/122999681

A cautionary note on anchor hooks

In autumn 2023, there was a fatal accident in Alabama. It involved a beginning climber who was cleaning an anchor hook anchor, that had a locking carabiner added to minimize wear on the hooks. The carabiner was removed, somehow the rope unclipped from the hooks, and she fell.

Short version: for anchor hooks, do NOT add a carabiner on the anchor for the rope. If you do toprope through your own equipment, extend quick draws or slings BELOW the level of the hooks, and put the rope through your own gear that way. This reduces, but does not eliminate, the risk of the above accident happening again.

Also, NEVER have someone clean an anchor who is not 110% solid on the correct procedure. The proper learning sequence should be: 1) instruction on the ground, until the person can demonstrate several times in a row the correct sequence. Then, 2) doing it with an instructor off the ground, hanging at the actual anchor, where they can be directly supervised. (This means NOT yelling instructions from the base of the cliff!)

Here’s an analysis of the accident from IFMGA Certified Guide Karsten Delap.

Here's another video from Karsten showing a few different methods of building an anchor with your own gear, and transferring to the anchor hooks when it's time to lower off for the last person.

So, why are anchor hooks usually placed with both gates out, and not opposite and opposed? I asked the American Safe Climbing Association, and they said:

“Anchor hooks are placed with gates out for a couple reasons. If opposed the inward facing hook tends to gouge into the rock and scar it up, along with orienting strangely to wear much faster on the nose or even get pushed into the bottom of the wiregate. If they are extended with chains to lay flat and opposed the rope gets pinched behind the hooks and wears unnecessarily/grooves the rock.

If the hooks are placed in very overhanging terrain this ceases to be a problem, but the opposition of the hooks still causes more friction on ropes and the hooks themselves, so we feel that because they are being used for lowering and the climber will always be beneath them gates out is the ideal configuration.

Obviously this all is dependent on the climber never being above the hooks - trying to clip into the system from the top of the cliff then downclimbing to set a toprope being a particularly dangerous scenario. There are many ways to dangerously misconfigure any anchor system and there will be no way to protect against all of them, but it is important that when a equipper places any type of anchor they consider how they are normally accessed. We have some guidelines on our Lower Off Initiative page detailing what to do if climbing above, etc.

Also, just as a matter of language, we refer to the CT wiregate hook as an "Anchor Hook" and the old style ones with the crappy gate as a "Mussy Hook", this is commonly misused but we stick to it as there is a difference and the Anchor Hook is purpose built for climbing applications with a stainless steel wiregate.”

Since we're talking about strength of horrendously worn out anchor hooks, let's look at the breaking strength of a NEW anchor hook, a steel carabiner, and a ram’s horn. (Data from HowNot2.com)

Keep in mind this is for a single pitch top rope anchor, where the forces will hardly ever be more 4kN.

New anchor hook: about 72! kN

Steel “gym” carabiner: about 49 kN

Ram’s horn: about 22 kN

Your climbing rope will break in about 14 kN, so anything stronger than that and you're good. In summary: way more than #SuperGoodEnough!

Here's a visual I like. 1 kN is about 100 kg, or 220 pounds. The way I like to think of it is the average weight of an NFL football player. There are 11 players on offense and defense playing against each other, so any point during the game there's 22 players on the team. Imagine 22 NFL football players all hanging from ONE 8 mm Dyneema sling that's rated to at least this amount. Or in this case one Ramshorn. To really get ridiculous, think of 72 football players all strung together, hanging off of an anchor hook.

Yep, that's plenty strong enough for your climbing.

The American Safe Climbing Association (ASCA) fully supports open anchor hardware for single pitch routes.

“The ASCA is committed to standardizing clip-and-lower style anchors on high traffic, single pitch routes across the country. In 2022 we provided over 5500 Lower-Offs through our Lower-Off Initiative. The majority were ClimbTech anchor hooks, but some ss and titanium went to wet/coastal areas. Along with the hooks, we supplied over 6000 quicklinks for attachment to existing anchors.”

Here's a photo from their website. (Note the hooks are both facing OUT away from the rock.) The ASCA started what they call the “Lower-off Initiative”. Hint hint: donating to a great organization that's actively trying to save your life is a great idea.

I asked them on Facebook to clarify their stance on lowering on open anchor hardware. Is it for everyone or just for the last person? Here's what they said:

“Our general recommendation is that everyone except for the last climber toprope/lower off personal gear, and the last climber in the party lowers off the fixed hardware. That being said - the gear we provide is robust and long lasting so don't feel bad if you go straight through the steel because you have concerns about a toproper not making it to the anchor or being proficient enough to move the rope over to the fixed lowering hardware. Our goal is less accidents.”

image; https://safeclimbing.org/lower-off-initiative

Munter hitch to clove hitch conversion

Are you belaying your second up on a Munter hitch? (Yes, old school, I know). Here is a very #CraftyRopeTrick to convert that Munter into a secure clove hitch once they arrive at the anchor. Even if you think you would never use this, it's a fun little bit of rope wizardry to practice. Check out the short video to learn how.

Yes, belaying your second from a Munter hitch is a bit of an old-school technique, but it can be helpful in certain situations.

Once your second arrives at the anchor (and is at a reasonably secure stance) whip out this clever bit of rope sorcery to convert that Munter into a clove hitch.

Doing this immediately secures them to the anchor, without any additional knots, tethers, etc.

It looks like a rope magic trick. After you flip the first loop back through the carabiner, you seem to have made a total tangle. But then unclip the correct loop, and that ungodly mess magically transforms into a clove hitch. #CraftyRopeTrick, for sure!

Yes, this technique does involve unlocking the carabiner gate and flipping the rope through twice momentarily. Provided the second is reasonably balanced and secure, this should not be a problem. Or, maybe this technique is just not for you and you can skip it, that's cool too. =^)

Note: the last movement of doing this, when you unclip one strand, requires you to be 135% sure you’re doing this correctly; otherwise there's a risk of you completely unclipping your partner from the anchor. Practice this a bunch and be sure you have it down correctly before you ever do it in the real world! If you're not sure you're doing it right, then don't do it!

There are at least two different variations on how to do this, I’m showing one. Even if you think you might not use this, it’s worth practicing just for the magic trick / entertainment value. :-) Like most things related to knot tying, it’s just about impossible to explain in words, but very easy to learn from a video.

Check out this nice video from Petzl Germany on how it's done.

Big wall water tips

For big wall climbing, water is the heaviest, and arguably most important, thing you can bring. Here are some solid tips for how much to bring, the best type of bottle, little-known material for a keeper cord, the frugal climber’s electrolyte mix, and even how to make a mini fridge in your haul bag.

Water on a big wall: How much to bring, and how best to store it?

It's the heaviest thing in your haul bag, so you don’t wanna take too much, but you definitely don’t want to run out either.

Good rule of thumb for quantity: 3-4 liters per person per day. You typically drink more lower down where it's warmer and the loads are heavier and less as you get higher up.

Start with sturdy bottles, with a secure lid, and a flared “collar” on top. The time-tested two liter pop bottle is a good choice for most of your water; plus, the round 2 liter bottles fit your round haul bag better. Bottles designed to hold carbonation are usually built stronger than a standard drinking water bottle. The collar, that’s just below the bottom of the cap, gives a secure place for your keeper cord. Bring some smaller one liter bottles to fill in gaps at the bottom of your bag. One liter bottles from Aquafina, holding non-carbonated water, are excellent.

Some people have luck with 1 gallon Crystal Geyser bottles, but I've had those leak on me. I prefer one and two liter pop bottles.

You do NOT need to put duct tape on the entire bottle, or use a “full-strength” sling.

Don't take a lousy, thin bottle, and try to reinforce it with tape. It's better to take an already solid drink bottle and don't use any tape on it.

Everything needs a clip in loop on a wall, including water bottles. While 3 mm cord is popular, I prefer thick twine called bank line. It’s super strong (300+ pounds!) inexpensive, and holds knots very well, see photo. I use about 24 inches of bank line per bottle. Tie one for every bottle; bank line is cheap.

Make sure your clip in loops are solid! If a loop fails the bottle will fall, and could seriously hurt or even kill someone. Use a constrictor hitch, which is similar to a clove, but more secure. (Check out the video at the bottom of the page to learn how to tie it, very cool knot.) Make sure that knot stays solid with a couple of wraps of hockey tape. Tie the string ends together with an overhand, good to go.

Speaking of hockey tape, it’s great! Think of it as heavy-duty athletic tape, that has superb stick-ability even when cold, wet, sweaty, etc. A few wraps of hockey tape around the neck of the bottle secures the clip-in loop. Taping your knot is fast and cheap insurance. Just don’t waste your time and tape covering the entire bottle. Bring a roll of hockey tape with you on the wall, it’s helpful for other things.

Water jugs to avoid . . .

Do NOT use those 1 gallon jugs with a built-in handle as shown below. The handle looks tempting, but the tops suck and will come off. You absolutely want something that has a solid threaded top.

Some people like the 1 gallon Crystal Geyser bottles, but the plastic is flimsy and I've had them puncture on me. The plastic in carbonated pop bottles is much stronger.

A few other tips . . .