Alpine Tips

Close your rappel system with the “J loop”

Hopefully you know the importance of “closing the rope system” by always having the rope ends tied either to a harness or a stopper knot. Here's an extension of that idea for multi pitch rappels: the J loop.

image: @seanisaacguiding, instagram.com/p/CJHp9lSjKBk/

On a multi pitch rappel, the first person down can add an important safeguard to the system by tying the rope strands to the lower anchor. This is known by some as a “J loop”, because it makes a big letter “J."

To secure the rope, you have several options. A clove hitch on each strand is a good choice. Because the hitch falls apart when you remove it from the carabiner, you don't have to remember to untie yet another knot. An overhand on a bight / BHK tied in both strands is also effective, because if you forget to untie it, you have a closed loop.

Avoid tying a separate bight knot in each strand. Why? Because it's all too easy to forget to untie it, start pulling the rope, and then realize too late that you have a knot above you, big problem!

On a traversing rappel, you need to be VERY careful to always control the ends of the rope. Using J loop can help you avoid the potentially very serious problem shown in the diagram below.

IMAGE CREDIT: ANDY KIRKPATRICK

How does the J loop help reduce your risk?

Your partner can’t rappel off the ends of the rope, because it's tied to the anchor.

It makes it much less likely that the ends of the rope can swing or blow potentially out of your reach after your second arrives and goes off rappel, which could be a VERY serious problem if the rappel is traversing, overhanging, windy, or some combination of these.

It makes it much more likely that the first person down will remember to untie the stopper knots in the end of the rope. (After the J loop is tied, the stopper knots are no longer needed.)

In a traversing or overhanging rappel, the J loop helps guide your partner more smoothly into the anchor.

Finally, in the extremely unlikely catastrophe of the top rappel anchor failing, all may not be lost, because the rope is tied to the lower anchor.

Here's a nice diagram from Petzl showing the method. Note the BHK / overhand knot in both strands, and the end of purple, the pull rope, already threaded through the anchor master point. (The purple rope does not yet have a stopper knot in the end of it, that's the next step.)

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Rappelling

For the first rappeller, the step-by-step procedure might look something like this. (This is one of several sequences that can work, not the only way.)

First person descending rigs for a standard rappel: using both strands of the rope, a stopper knot in each end of the rope, and an autoblock backup.

First rappeler arrives at the lower anchor. Clip tether to anchor. Keep your rappel device and auto block on the rope for now.

Feed 2-3 arm lengths of slack through your rappel device and auto block so your partner can get started.

Yell “off rappel”.

Optional but recommended: test pull. If your partner is not pre-rigged, do a test pull of the rope by pulling down a few meters on the pull strand to be sure it moves properly. Your partner above can answer this silent signal by pulling the rope back up. Be sure you have discussed this beforehand, so your partner up top knows what your test pull means, otherwise they might have a mild freak out. (If your partner is pre-rigged, you can’t do this step, because their auto block holds the rope in place.) If communication is difficult, note that the test pull can be a good non-verbal signal that you’re off rappel.

Tie a clove hitch in each strand and clip it with a locker onto some strong component of the anchor. Leave about 2 meters of slack to form the “J”. This slack allows you to do a test pull, and gives the second enough rope to descend.

Sweet, the rope is now secure in a J loop. Give yourself a high five. =^)

Untie the stopper knots in the end of each rope strand; you don't need them anymore.

Your smoking hot rappel device has now cooled off. Remove the rope from your rappel device and autoblock.

Pass the “pull” strand through the anchor, and tie a stopper knot in the pull end.

Wait for your partner to arrive. If for some reason they're not using an auto block backup, you can give them a firefighter belay. If they do have an auto block, there’s no need for the firefighter belay. That gives you a little break, whew! Use it to check the weather, grab a snack/water, get out your headlamp, scope the next rappel, read the topo, etc.

Once your partner arrives and is tethered to the lower anchor, untie the clove hitches.

Have a quick systems check: Both partners safely tethered, no twists or crosses in the rope, knot removed from the strand that’s going up.

Pull the rope slowly. Keep control of the end of the “up” strand until the last moment; don't let go of it and have it swing out of reach before you have to. (If the rope gets stuck as you're starting the pull, keeping control of the “up” strand greatly increases your options to solve the problem!)

Showa fishing gloves: the go-to for cold and wet?

Could these $20 Japanese fishing gloves become your go-to for winter sports? Many top climbers are increasingly saying yes. Let's take a closer look at Showa gloves, see an ice water “torture test”, and learn the one model you probably want to get.

Why are Showa fishing gloves great for cold-weather sports? How about: waterproof, durable, lightweight, warm, good dexterity, and incredibly inexpensive?

Could some of the best all-around winter gloves really be . . . fishing gloves from Japan that cost around $20?! Maybe yes.

In the last few years, more and more climbers have quietly started using some strange looking gloves from Japan. Made by Showa (and known in some circles as a “Smurf glove”, because of the garish blue color of many models) these just might become your go-to gloves as well.

I first heard of these from IFMGA certified guide Silas Rossi, in a YouTube video he made about his glove systems. In the midst of talking about his dozens of different gloves, at 4:17 he casually mentions, “The best all-around glove I probably use most days are these fishing gloves from Japan . . .”

Colin Haley is a fan as well. Here’s a “what’s in my pack” type article where he praises them, and below is a screen grab from his video of his solo speed record on the Cassin Ridge on Denali, with the gloves airing out at a break.

image: Colihn haley, screen grab from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zD6YZkgUYHg

Also, backpacking expert Andrew Skurka has advocated these gloves for several years.

Apparently Japanese climbers already love these gloves. (This page is in Japanese, try right clicking and choose (“Translate to English”.)

So . . . if these expert climbers and backpackers, who demand top performance and test their gear ferociously, give these a thumbs up, there just might be something to it. So I got a pair to check ’em out.

At first glance, these look a bit like heavy duty gloves you might use for grubbing around in your garden. They’re made from an industrial looking fabric that's been hot dipped in some kind of waterproofing rubber. They have a light fleecy liner, which keeps your hands comfortable even when it gets a bit damp. They are billed as breathable and waterproof, but I think of them a bit more like a wetsuit glove - even with some internal dampness, your hands still stay warm.

You may not want to wear them under heavy exertion/sweating, like hiking or skinning uphill, as your sweat is going to dampen the glove a bit. Drying them can take a while, but like most gloves, turning them inside out helps a lot. (When you’re sweating, like skinning uphill, a better choice might be a breathable fleece glove.)

In colder conditions, some people have success wearing a simple nitrile glove as a vapor barrier liner underneath the Showa gloves. (I haven't tried this, but it sounds like a good system.)

The light fleece liner is going to get chewed up under heavier wear. When that happens, add your own lightweight liner gloves underneath the shell.

If you search online, you’ll see MANY different styles of Showa gloves (in some shade of blue) that all look about the same.

For snow sports and alpine climbing, there’s one model that’s most suitable:

Showa 282-02 Temres

This model differs from the others because it's 1) black and 2) has a nylon wrist gauntlet that cinches down on your forearm and helps keep out the snow. The many other models of Showa gloves do NOT have this wrist gauntlet. Those other styles might be suitable for cold-weather backpacking or rainy bicycle rides, but to help keep out the snow, the wrist gauntlet is a big help.

Although the fit is a little loose, because the liner is bonded to the shell, you have greater dexterity than you might think. Tying climbing knots, securing a harness buckle, swinging ice tools, good grip on the rope for belaying . . . no problem!

They are lightweight. A pair of the Temres (size large) weighs just 115 grams / 4 ounces.

Like lots of Japanese clothing, these are sized small by North American standards. My hands are a medium with just about every other glove, but a large here fits me perfectly. The gloves do come in XL and XXL sizes, so if you’re wondering, you might wanna go a size bigger. Heck, they’re inexpensive enough so you might want to buy two different sizes and just give away the one that doesn’t fit.

Are these going to be the perfect gloves for every single winter sport? No. For super-cold weather, you may want more insulation (and maybe mittens, which will almost always be warmer than a gloves). If you rappel a lot, you may wear through the palm. If you're actually rock climbing in them, you may need a thinner glove with more dexterity.

But maybe for 90% of the things you do in the snow, like digging snow pits, brushing snow off the tent, approach hiking, racking your gear, excavating your car, snowball fights, walking the dog, etc., this might be the ticket. I don't do snowmobiling, but they look perfect for that. And I've been on some very cold multi day whitewater trips when these would've been amazing.

As a test, I put on the Temres glove and stuck my hand in a bucket of ice water. (Bonus, 28° Fahrenheit air temperature with snow on the ground.) After 15 minutes, my fingers were toasty warm and completely dry! Try that with any other glove and see what happens.

Sounds good! How do I get some?

At this writing (Feb 2021) there’s only one place that I know in the USA where you can buy the Temres 282-02: Go2Marine.com in Bellingham Washington. (I’m sure they are wondering why the hell they’re getting hundreds of orders for Japanese fishing gloves but hey, good business for them.)

As a reminder, there are no ads, paid product promotion, or affiliate marketing links at AlpineSavvy. This link is mentioned only as a convenience for you.

You may have heard the car mechanic’s saying: “You can have it fast, good, and cheap. Pick two.” It seems gloves usually work the same way; There needs to be some sort of compromise along the way.

Happy surprise: the Temres 282-02 gloves deliver on all counts.

Top rope directional for ice and rock

For top rope climbing on rock and especially ice, having a directional placement off to one side of the anchor has many benefits. Learn them here from guest author, ACMG Guide Sean Isaac.

Photos and article (used with permission) are from Sean Isaac. Sean is an ACMG (Association of Canadian Mountain Guides) certified Alpine guide, a former professional climber, and author of the “Ice Leader Field Handbook” and “How to Ice Climb” (2nd ed.) Follow @seanisaacguiding for more great tech tips.

Using a directional protection point in top-rope ice climbing can significantly reduce risk and increase climber enjoyment. A top-rope directional should be used more often than not for many reasons.

One of the main ones: keep the belayer’s side of the rope away from the swinging ice tools of the climber. When rock climbing, it’s annoying when the belay rope slaps the climber in the back of the helmet, but in ice climbing this can be a major hazard. The climber can catch the belay rope behind them as they swing, which can result in either dropping the tool or putting a pick in the rope (I’ve seen both examples happen).

In addition, a top-rope directional helps to:

Keep the rope in line with the route and between ice tool placements (less chance of hitting the rope)

Keep the rope out of wet ice

Prevent a pendulum swing into hazards: ice pillars, hanging icicles, rock corners/dihedrals

Create two separate climbing lines from a single top-rope anchor

Keep the rope away from loose rock or sharp edges

Prevent swinging out away from the rock on steep mixed routes

Prevent climbers from going higher than you want them to (i.e. over a bulge, too close to an ice anchor, out of sight, etc)

Prevent the two strands of rope from crossing and twisting around each other

Almost any type of protection can be used as a top-rope directional including: ice screw, V-thread, tree, bolt or rock gear.

Some common concerns . . .

“Isn’t that some sort of American Death Triangle (ADT) vector, which increases forces on the main anchor and the directional?” It's not an ADT because the force doesn’t come to one point. Actually, having the directional decreases force on the main anchor, because the directional takes some of the force. For a good ice screw that can hold at least 10 kN, it’s not a concern.

“If the directional fails, doesn't it shock load the main anchor?” The directional should never fail. (If it's a warm day or the anchor is in direct sun and you're worried about the screw melting out, then making a V thread might be a better choice.) In the highly unlikely event that it fails, you're going to take a swinging lateral fall onto a very stretchy dynamic rope. Which could certainly be exciting, but not an issue for the main anchor.

Does it twist the rope? As long as the directional is below the elevation of the main anchor, the rope doesn’t get twisted. (In the small chance it does, try this simple trick to remove the twists.)

A caution: Be sure your rope is long enough. If you add a directional, this increases the length of rope required to lower to the ground. For an ice anchor directional of just a few meters as shown above, that shouldn’t be a problem. However, if it's a rock route with bolted anchors that are exactly placed, for say, a 30 meter climb, you might need more than a 60 meter rope if you add a directional. One more reason to always close your rope systems with a stopper knot.

If the directional is critical to avoiding a specific hazard, then a locker draw (below) can be a fine idea. (There are lots of other uses for a locker draw, learn them at this article.)

Using your phone to measure slope angle

Knowing the slope angle you're standing on can be helpful for assessing avalanche risk. The old school method of a clinometer on your compass can be a hassle. Instead, try a measure/level app on your phone.

Measuring slope angle, to assess avalanche potential or brag about how steep that final couloir was to your friends, can be useful in the backcountry.

The old-school way of doing this was with a sort of plumb bob on fancier compasses called a clinometer. Truth is, using one is often a hassle. You may find it hard to read the tiny numbers on the compass, and usually have to have your cheek down in the snow to be able to look at the compass. About the only advantage is that it doesn't need batteries.

A more modern and way easier way to check slope angle is with some sort of “Measure/Level” app on your phone. The iPhone has one built in to the operating system. Or, you can get a free measurement tool from BCA Backcountry Access. (Android folks, I'm sure you can find something similar.)

Open the Measure/Level app on your iPhone, and swipe to open the Level app. If you're walking / skinning uphill, simply put the phone flat on your ski, or on edge if going across the slope.

Note: Just knowing the slope angle is not the whole story as far as avalanche potential. Avalanches are often caused by micro terrain features that you may not notice by taking a quick measurement like this. Or, you could be on a safe slope, but there could be an unsafe slope above, with you in the run out zone.

At top is a photo showing how it's done, from the expert backcountry ski guides at Graybird Guiding. (Note, an uphill skin track of about 18° is thought to be about optimal, so keep that number in mind.)

Note that phones don't behave well in the cold. If you use it for occasional slope measurement, try to put it back in an inside pocket, ideally in your base layer between uses. Carrying an auxiliary battery at full charge, also kept warm, with a short charging cable, is highly recommended.

If you have an iPhone, this measuring tool is free as part of the operating system.

However, for just a few bucks more, you can get an iPhone and Android app that's quite a bit better. Search the App Store for “Avalanche Inclinometer” (made by Iterum LLC). As of winter 2024, this app is $3.99.

This upgrade has some handy and easy to read features: the slope value is color coded to remind you when you might be getting into higher risk terrain, you can tap to lock the screen, and it also shows your elevation, aspect, and coordinates. With a tap you can share all this information via email.

CalTopo pro tip: Travel Time and Travel Plan

CalTopo, the best backcountry mapping tool, has a very cool feature - Travel Plan. Draw a line or import a GPS track, then add waypoints on the line that break the trip into segments. Now, choose travel plan, and you get a table showing distance, bearing, elevation gain and estimated travel time between each leg of your trip.

CalTopo, the best backcountry mapping desktop tool, keeps getting better. CalTopo recently (autumn 2020) rolled out a very cool feature(s), “Travel Time” & “Travel Plan”. Let's learn how to use ‘em!

(If you’re new to CalTopo, get started with this tutorial video.)

CalTopo has four subscription levels: Free, Basic, Pro, and Desktop. I recommend the Basic for most users, but if you want the Trip Planning feature, you need the Pro or Desktop. See more details on the subscription levels here.

For this example, we’ll use a backcountry ski circumnavigation tour of Mt. Hood in Oregon.

The “Travel Time” feature is available for all subscriber levels. If you draw a line (right click on the map > New > Line, or use an imported GPX track), click on the line, and select Travel Time, you’ll see an estimation of travel time for that line. This time is estimated using the “Munter Method”, which considers distance, elevation gain/loss and travel mode. It’s a rough estimation, but can be a good starting point. (Learn more about the Munter Method here.)

(And, because I know you're wondering, yes, it’s same person who popularized the Munter hitch, Swiss guide Werner Munter! Thanks for both of these, Werner!)

A good way to test the accuracy of the Travel Time estimate is to draw a line covering a familiar hike or climb, and test the predicted time with your normal hiking time. For example, I did a test drive of the standard south side route on Mt. Hood. CalTopo predicted a travel time of 5.4 hours on foot, which is pretty much spot on with the standard 5 hours that's typical for a fairly fit climber.

Of course, alpine travel times can be extremely variable depending on fitness, snow depth, amount of crevasse negotiation, etc. This is a baseline for general trip planning, not the Holy Grail.

First, draw in your route or, in this case import a GPX track.

(Sidenote: AlpineSavvy has GPX tracks for more than 70 of the most popular climbing routes in the Pacific Northwest available for free download, you can get them here.)

Right click on the line, select Travel Time, and you should get a box that looks like the one below.

The Travel Time is moderately helpful. But for Pro level subscribers or higher ($50+ a year), you get another big level of Awesomeness, the Travel Plan. With this, you can add marker points along your track, click “Travel Plan”, and then get a table of very helpful route information between each point. Here's how to do that.

First, add some marker points (aka waypoints).

Right click on the line on your map, map, choose New > Marker. The marker points need to be pretty much on the line that you drew or imported.

It's good to add marker points that break up the route into reasonable sections. In this case, that’s significant ridge crossings or entering/exiting large glacier areas.

It’s helpful to give the marker points a common name, and then a number. This helps keep them organized in your GPS app, as well as letting you quickly see where the next one is sequentially when on your trip.

Additional cool feature: You can include Travel Plan break times by typing “30 min” (or whatever time you like) in the marker label field or marker comment field. Click the marker and choose edit to access the comment field. Example below.

Now, you can click the track, click Travel Time, then click Travel Plan.

Travel Plan creates a table like this. For each waypoint, it shows the latitude longitude coordinates in decimal degrees and the elevation. From one point to another, it shows vertical gain or loss, distance, true north bearing, estimated time, and cumulative time.

A few notes . . .

If your pace is significantly faster or slower than what the Travel Plan predicts, you can adjust this in the Travel Mode “Custom” drop down box.

You can print this out, take a screenshot, or save as a PDF (helpful if you want to share it with other people on your team.)

For a longer trip or multi day outing, you can create a single travel plan that covers multiple lines / tracks. That’s more advanced than I want to cover here; learn how on the CalTopo training website.

So . . . why is the CalTopo Travel Plan cool?

Backcountry travelers have been making travel plans like this for years. But, it required extremely exacting work of counting contour lines, measuring distances with the map scale bar, and some math that many people found to be about as enjoyable as chewing on tinfoil. Caltopo does the same with just a few clicks, and saves huge amounts of time and tedium.

Because you know distance and bearing between marker points, it helps you keep your GPS phone app mostly in your pocket, and follow a compass bearing (compasses, remember those?) and general terrain between points. In alpine terrain, it's usually easier to navigate to a specific waypoint, taking the path of least resistance, then try to stay precisely on top of a GPX track. Doing this helps save your phone battery, and increases your situational awareness, because you're paying attention to the landscape around you and not staring at a GPS track on your phone screen.

It lets you have a better sense of your pace and what a realistic turnaround time or a bail out point might be. Rather than having one strict turnaround time for a particular point of your trip, you can compare each leg with the estimated time to get a more detailed sense of your overall pace.

Related to the previous reason, it lets you share a solid travel time with an emergency contact person at home. Many unnecessary rescues are initiated because a hiker underestimated their travel time. This tool can give you a more realistic estimate, which you can hopefully share with your contact person, maybe sparing them needless worrying and even calling for an unneeded rescue.

Finally, if you want to get fancy and have some time on your hands, you can export the GPX track from CalTopo as a KML file, and then open the KML in Google Earth. If you do a fly around, it looks something like this. (Of course, this ski tour is more fun with more snow.) Enjoy!

Backcountry ski repair kit tips

Headed out for a backcountry ski trip? You’d better have a way to fix your gear. Here are some components of a robust repair kit that can handle just about everything. (Thanks to a few ski experts who contributed to this: Pro Guiding Service and Matt Schonwald.)

The bulk of this article comes from the experts at Pro Guiding Service in North Bend WA. Follow them on Instagram, Facebook, and check their website, proguiding.com. Photo and content shared here with permission.

Some other suggestions on this page come this article from Matt Schonwald, an AMGA certified Ski Guide, Avalanche Instructor and member of Northwest Avalanche Center’s Forecasting Team. Connect with Matt at BC Adventure Guides.

Backcountry ski repairs can fall into into two major categories.

Category 1: a bummer, but you can keep moving.

A broken ski pole

Lost ski pole basket

A tear in your clothing

A broken walk mechanism in your touring boot

A bent ski

A delaminating ski

A lost skin tail clip

A lost or torn skin tip attachment

A broken heel piece in a pin binding (this a category 1 if you’re a good skier)

Category 2: a major bummer and potential safety issue.

A broken toe piece in a tech binding

A toe piece torn off a ski

A ripped out binding

A lost skin

photo: https://www.facebook.com/ProGuidingService

Here's a repair kit that can handle just about all of these situations, and a few more.

A few notes . . .

This is more of a kit that a ski guide might carry on a longer tour or multi day outing. A few things, like the toe piece and cordelette, can probably be left at home if you’re on a shorter or less committing trip.

Just like sharing the contents of a first aid kit, no one‘s going to agree 100% with everything. This is more of a starting point to get you thinking about what gear you might want to carry.

Do you think this gear is too “heavy”? I don’t know the exact weight of everything posted here, but it can’t be much over 1 pound. If that amount of weight is keeping you from your objective, consider spending more time training and less time obsessing about shaving grams from your gear. =^)

(Reminder, AlpineSavvy has zero affiliate marketing. The links are provided only for your convenience.)

A few zip ties. Consider steel zip ties, they are stronger and can hold up better in cold weather. You can also get heavy duty zip ties that can hold about 200 pounds/100 kg.

Some 2 mm cord

A meter or so of wire; 16g is a good size; stainless steel is best so it won't rust in your pack.

Fabric repair tape; Tear-Aid (type A) tape is good.

Small roll duct / Gorilla tape; Consider cloth hockey tape. It sticks well to things that are wet and cold.

Epoxy; this may make the difference when you tear the toe piece off your ski. You can get single use epoxy packets that are more convenient to carry.

Assortment of hose clamps; two small ones for pole repair, and two large ones to clamp your boot to your ski in case your binding breaks. Large hose clamps not shown in photo.

Some sort of pole splint; 15 cm length of old ski pole tube with a slit cut lengthwise. I've heard of people using a section of aluminum can for a pole splint, never tried it.

Assortment of standard binding screws; if you have a quiver of different skis/bindings, be sure you bring screws that cover everything.

Helio coil inserts for torn out bindings screws; steel wool and epoxy can serve the same function.

A multi tool with pliers and wire cutter; the Leatherman Skeletool, 5 ounces, is a good choice.

Binding Buddy; heavy, but works well. Test it and be sure that it's long enough to reach every screw on your binding, sometimes the neck can be a bit short. The Topeak Ratchet is another option for a driver that has more leverage.

Assortment of driver bits to use with your Binding Buddy or Skeletool. #3 Phillips, #2 Phillips and T20 (Torx / star bit) can be a good start, but check all your gear and be sure you have bits for everything. It's not standardized. Some gear requires Allen screws, typically #4 or #5.

Allen wrench; if your boot has any Allen bolts

4 bolts and wing nuts and a 6mm cordelette for potential construction of rescue sled; sorry, no link for this.

Glop Stopper wax; Black Diamond, glide wax for your skins, carry a small piece, not the whole big block

Glide wax

Metal ski scraper

Tent pole splint; for fixing a broken ski pole, you can also cut a section from an aluminum can

Skin tip

Skin tail clip. Can't really improvise this.

Extra ski pole basket

Voile ski straps. Bring a pair, 24 inches is a good length. Good for loads of things in addition to the obvious holding your skis together. These are in addition to the ones you have to hold your skis together. Here's a whole article on Voile straps.

Finally, a sturdy bag to put it all in. You can go bare bones with a stuff sack, or something that zips open and has a few dividers like a bag for a first aid kit.

For longer or more remote trips, consider:

Two cordelettes of about 6mm/ 6 meters long. For general anchor building and rigging a rescue sled if needed.

A few carabiners

Flat overhand bend - how long a tail?

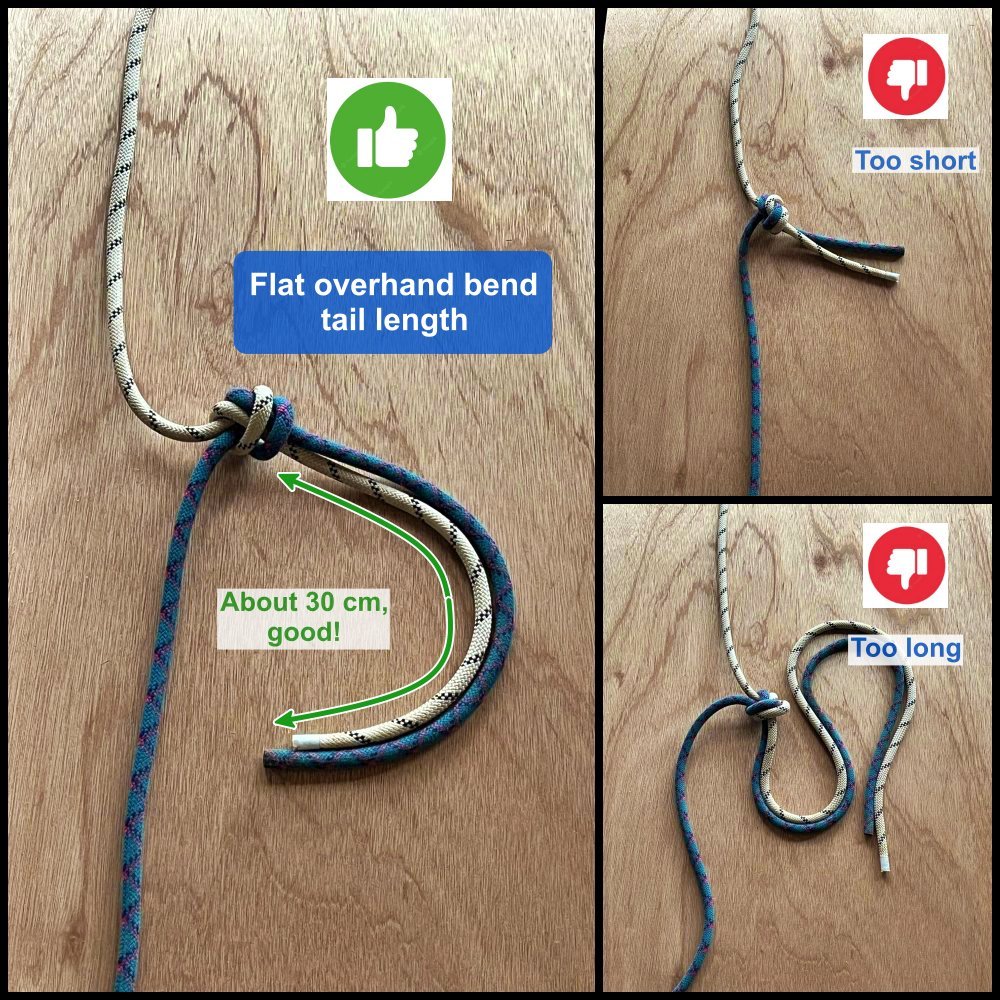

A flat overhand bend is a good choice for connecting two ropes for a double strand rappel. Pay attention to the tail length. You want it at about 30 cm, or the length of your forearm; not too short and not too long. Longer is not better, and has been the cause of fatal accidents.

A great knot choice to connect to rappel ropes for a double strand rappel is the flat overhand bend. (It was previously known by some as the “European Death Knot”, or EDK. Let's not call it that anymore, okay?)

Why is this a good rappel knot?

It’s known as an “offset” knot, because the body of the knot is offset from the line of pull. This can help the knot work its way around obstructions such as rock nubbins or ledges to lessen the chance of it getting hung up when you pull your rope.

Works well with ropes of different diameters (up to about 3mm difference). So if you want to connect a skinny 7.7 twin rope with a 9.5 single rope, no worries.

Super easy to tie and visually check.

It's plenty strong for any normal two strand rappel situation. (For a single rope rappels more common in caving and canyoneering, or for extra heavy loads, some recent research recommends a more robust knot. We’ll cover that in a future tip.)

It’s important to have the right amount of tail in the flat overhand bend. A good rule of thumb is about 30 cm / 1 foot.

Think of that as about the length of your forearm, or two hand spans. It's sort of the Goldilocks length, not too short and not too long. This length gives you a margin of error to prevent minor mistakes from becoming catastrophic.

If the tails are too short, the knot could potentially roll once or twice under an extremely heavy load and roll off the ends. A decent sized tail (hopefully) prevent this.

If you tie a sloppy, poorly dressed knot, a proper tail allows the knot to tighten up under load without pulling in the ends.

Not-too-long tails give you use of the full rope, which can be important in reaching the next rappel station if it's a real rope stretcher and you need every possible meter.

Proper length tails keep your nervous partner happy, and gives them room to add another overhand knot (aka stacked flat overhand bend) in the tail if they like, to give them a warm fuzzy feeling before they rappel. =^)

Many people think a longer tail is better. Not so. If the tails are too long, it increases the chance of someone mistakenly clipping their rappel device to the tails rather than the actual rope. While you may think this would never happen to you, this has caused fatal accidents to extremely experienced climbers, usually in darkness and/or from major exhaustion. Eliminate this potential mistake by having tails not too long, but just right.

If for some reason you’re ever fixing a rope (or using someone else's fixed rope) or tying two together like this, and the tails are longer than about 30 cm, at the very least tie a stopper knot in the ends, or tie them together, or do something to prevent someone from ever rapping off the ends.

Here are two accounts of tragic accidents where someone rigged a fixed rope with a long tail, and rappelled off the tail instead of the actual rope.

Fatal accident: Rappelling off the long tail of an anchor in Yosemite

Fatal accident: Rappelling off the long tail of an anchor in Baffin Island

Shaded relief - helpful, and a fun optical illusion

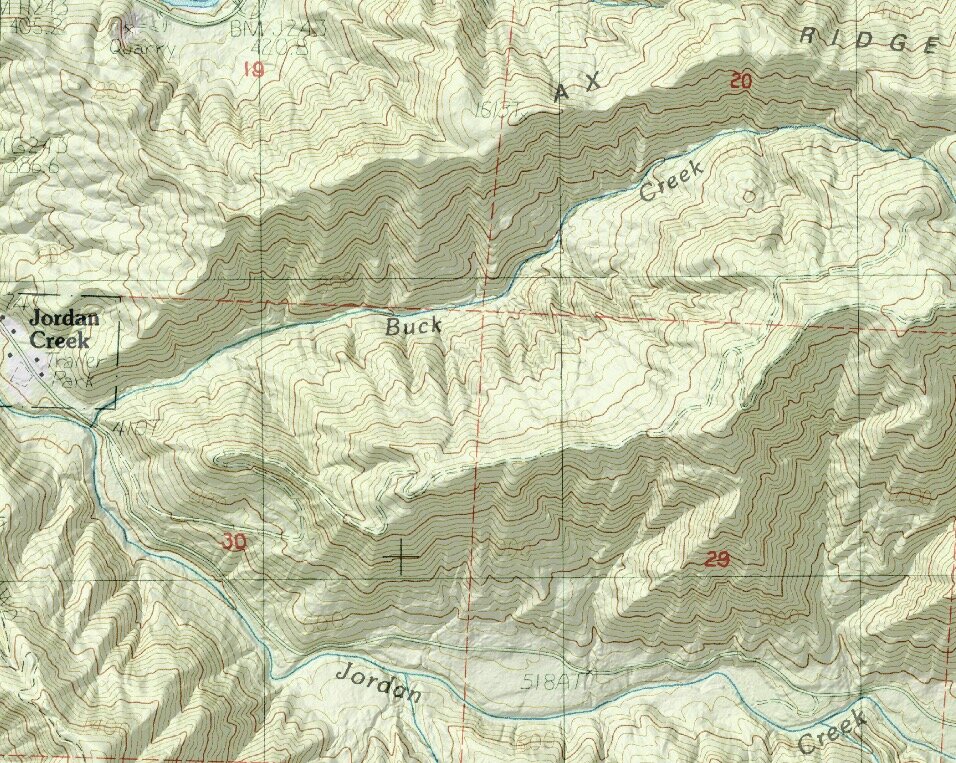

Shaded relief, a.k.a. hill shading, is a cool cartographic trick that helps you see topographic maps in more 3-D. While it’s very helpful to see features like creek drainage and ridgelines, it also is a cool optical illusion - if you turn the map upside down, the creeks and ridges reverse! It's a better show than a tell; check out the examples in the article.

An ordinary topographic map can look like a big bunch of squiggles, and it takes practice to “read” the contour lines to make out landforms like ridges and gullies. A clever bit of cartographic wizardry known as “shaded relief” (aka hill shading, or terrain shading) tricks the brain into seeing terrain features such as ridges and gullies more in 3-D, extremely cool!

Here’s a side-by-side example of the exact same terrain. The top map is the standard topographic map, and the contour lines mostly look like a spaghetti pile. On the bottom is the same area with shaded relief added. You can clearly see the streams and ridgelines, nice!

So, here's the fun optical illusion part. If you turn the shaded relief map upside down . . . The streams appear to be ridges, and the ridges appear to be the drainages! Check out the map below. Jordan Creek and Buck Creek appear on a ridge . . . but you know creeks don't go on ridges! If you're seeing this on your phone, you can take a screenshot and turn it upside down also.

Pretty cool, no?

This does have some occasional practical use in the field. If you have a shaded relief map, and you rotate the map so south is at the bottom (called orienting the map, which you might do when walking south) be aware of this illusion, because what you see on the map might well trick your eye.

Some navigation experts claim that you should not use shaded relief at all because of this potential for error. I disagree. The huge increase in legibility for the average user is a massive benefit that far outweighs the potential eye trickery when you may occasionally view the map upside down.

You can create shaded relief maps like this for free from the great mapping website Caltopo.com. Lots of Caltopo is free, but for a modest $20 annual subscription you can access even more. If you love maps, please consider a subscription to support the creators of this very helpful mapping tool, hint hint.

Learn to use Caltopo from this YouTube video.

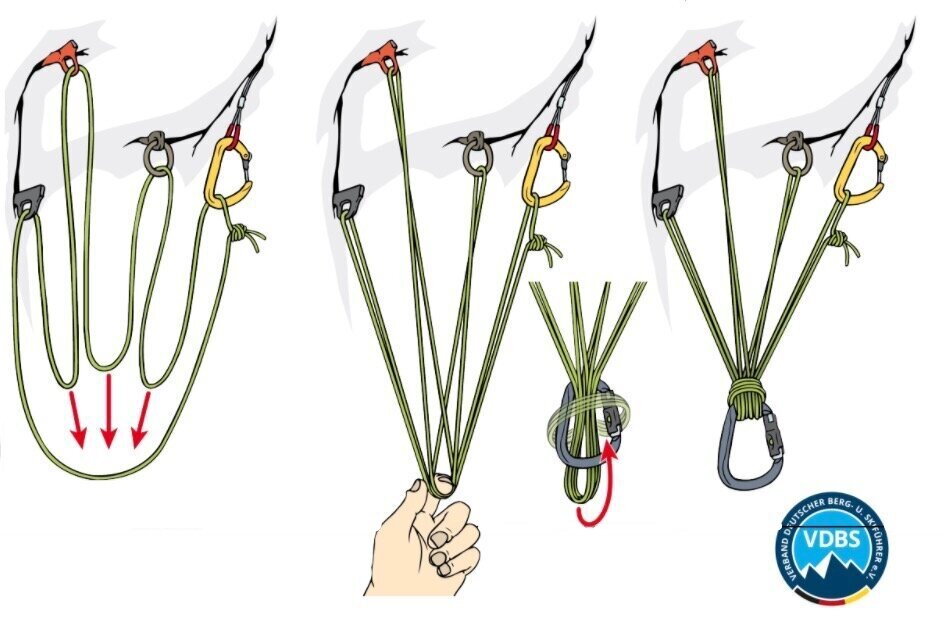

How to clip a piton

When clipping a piton, try to clip and then rotate the carabiner so the gate is facing out and the load is along the spine. If that doesn't work, you might be able to skip the carabiner entirely by hitching a sling to the pin.

When clipping a piton, try to flip the carabiner so the spine is against the rock. The gate opening can be down (center) or up (right). Doing this aligns force along the spine of the carabiner, the strongest orientation.

If you clip with the carabiner gate facing the piton hole, the carabiner can be sometimes levered in strange ways, and could potentially even break under a heavy load. In the photo on the left, we can see this happening a bit. Depending on the style of carabiner and piton placement, this can be more or less pronounced.

And, if you find that the carabiner is being loaded in a way that you don't like no matter what you try, you can thread a sling or cordelette directly through the piton hole. Of course, avoid doing this if the piton hole is chewed up, as it might damage your sling.

Below are two examples from the German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (“Verband Deutscher Berg und Skiführer” or “VDBS”).

You can see more interesting VDBS approved anchors at this article.

IMAGE CREDIT: CHRIS SEMMEL / VDBS

IMAGE CREDIT: CHRIS SEMMEL / VDBS

Aiding - Clip gear as high as you can

Aid climbing, they say, is a game of inches. When leading, you can get extra reach out of each placement if you try to clip your aider as high on the gear as possible. With a cam, this usually means the thumb loop.

When leading on aid, standard practice to get maximum reach is to try to clip gear as high as you can.

Let's start with a bolt. Typically, you clip your ladder directly to the bolt is shown below on the right, as this gives you maximum reach. If you clip a quickdraw first, and then clip your ladder to the top carabiner of the quick draw, you're losing a few inches. Pretty much all modern both hangers have enough room for two carabiners, that's why this works.

Sometimes you may have strange hangers that can only accommodate one carabiner, or maybe you're leading a roof where it makes more sense to clip the quick draw first, but those situations are pretty rare.

When you place a cam, you usually (depending on cam design) have three different options of where to clip it:

the racking carabiner

the sling

the wire loop

The wire loop is generally best for aiding, because it gives you the highest reach. (Note that some cams, such as the Metolius Master cam, don’t have a wire loop.)

Note that clipping the wire loop decreases the rated strength of the cam by about 1-2 kN, due to the sharper angle. But, it's just for your body weight and not for taking a fall, so in this case it's fine.

Let's look at these three clipping options in the photo below.

Left: Aid ladder clipped to the racking carabiner of the cam. Not ideal, you're losing about 8 inches of reach. Clip it higher if you can.

Center: Aid ladder clipped to the sling. Slight improvement, but let's see if we can get a little higher.

Right: Aid ladder clipped directly into the wire loop. This gives you the most reach, and is usually the best option.

While most modern cams are designed with wire loops that can handle your body weight and even maybe a bounce test without getting too abused, older ones (below) may not. Repeated aid climbing can damage the cable housing and potentially kink the cable a bit. Newer style cams with more robust thumb loops generally don't have this problem. Here's a photo of my beloved old orange Metolius that’s not in the best condition. =^(

How does your belay device affect impact forces?

Many climbers avoid using a Grigri (or similar device) when trad climbing, because they think the sudden braking action is going to dramatically increase the force on the top piece of gear. Is this something to worry about? Petzl did some testing on this, and the results are (mostly) reassuring.

“You should NEVER use a Grigri for trad climbing, because it puts too much force on the top piece of gear.”

Have you heard some version of this?

There are plenty of (often very experienced) climbers who trad climb with a Grigri, and they're not ripping gear out of the crack every time they take a fall, so what's the deal? (Actually, using a Grigri for alpine rock climbing has a host of benefits, which we cover at this article.)

I've also heard absolute numbers tossed around, such as, “Using a Grigri increases the force on the top piece of gear by 30%.” Percentage increase in force is not nearly as important as the actual force. For example, if the force on the top piece of gear goes from 2 kN to 3 kN, that's a large percentage increase, but a rather small numerical increase.

Fortunately, the clever gear testing gnomes at Petzl did some testing on this, and the results are interesting!

Petzl compared falls of increasing severity, using real live belayers and climbers. They measured the force on the climber, the top piece of gear, and the belayer.

Check it out here, or click the button below.

(There's a nice video of the test climbers catching big whippers, always fun to watch!)

It's important to note that falls involving real people have a much different (usually lower) forces then those typically measured in the harsh environment of a drop tower. This is typically due to belayer displacement, squishy human bodies, and some rope slipping through the device as braking is applied.

(With real people, you can't really test past factor 1 because someone's probably going to get hurt.)

Keep in mind these are not absolute rules for every kind of rope, belay device, etc. From the Petzl web page: “The results are influenced by slippage in the belay device and therefore by the belayer's grip. Variability is thus high: these results cannot be generalized to all situations and allow us only to quantify, in a broad sense, the influence of the belay device.”

If your French is a bit rusty: the gray dot is the top piece of gear “l‘ancrage”, the blue dot is the force on the climber “grimpeur”, and the black dot is the force on the belayer “l’assureur”.

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Influence-of-the-belay-device?ActivityName=rock-climbing

For a Grigri belay with larger fall factors (0.7 and 1.0) the force on the top piece of gear is about 2 kN higher than a belay with a Reverso. The highest force measured overall was 6 kN (factor 1, with a Grigri, on the top piece of gear). Not catastrophically huge, but potentially concerning, depending on the quality of that top placement.

However, for the more common lower fall factor of 0.3, the Grigri generated only a very minor increase in force on the top piece of gear. That’s good!

Comments . . .

The takeaway: provided you can keep your fall factor relatively low, and you have good placements in good quality rock, using a Grigri for trad climbing is fine.

It's not the Grigri that's solely responsible for increased force, but more the amount of dynamic rope in play to help absorb the force.

Fortunately, high fall factors are rare and usually avoidable. Here are some ways to mitigate them.

If you're on a multi pitch route and looking at marginal gear and/or hard climbing right off the anchor, it might be best to belay with a tube style device or munter hitch. Once the leader has a few good placements and has some dynamic rope in the system, fall forces should remain low, belaying with a Grigri should be fine, if you want to (carefully!) change belay devices

A downside to using the Reverso (or similar device) is that by giving a softer catch, your climber might fall farther. This can obviously be a problem if there's a ledge or (ground) below them.

Want to learn more? See these articles that cover similar studies by Petzl.

Anchor overview - a German perspective

The German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (VDBS) published a short PDF file of recommended anchor building practices. Many of them are strikingly different than those used in many parts of the world. Let’s learn some new anchor setups!

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS

The German Mountain and Ski Guides Association (“Verband Deutscher Berg und Skiführer” or “VDBS”) has a well deserved reputation for professionalism and technical expertise.

German Mountain Guide / Bergfuhrer Chris Semmel published an interesting PDF file that summarizes some modern, “VSBS approved” approaches to anchor building.

Many of them are quite different than what's used in the United States, so let's have a look!

Suggestion: When we encounter a technique that’s different from the one we currently use, it’s good to keep an open mind. There are few absolutes in climbing, “gotta do it this way or else”. Most everything else is somewhat subjective. Always practice new methods on the ground first, ideally with a qualified instructor.

A few notes . . .

All images on this page are credited to Georg Sojer, Chris Semmel and the VDBS.

Side note: Georg is a superb and funny cartoonist! Follow him on on the Insta: @sojercartoon

Many of these anchors originated in the “South Tirol”, (Dolomites) which is in northern Italy and not Germany, but credit still goes to Chris and the VDBS. Let's not get hung up on country of origin here, okay?

Graphics with the “VDBS “ logo are the recommended practice. Graphics without the logo are “alternative” methods.

The images are screen grabs from a zoomed in PDF file, so sorry if the quality is not so great.

I'm sure there are some native German speakers reading this who might take issue with some of my translation. I had help from a friend who is self-professed 90% fluent, so any mistakes I blame on him. =^) Let's stay focused on the image content and not get bogged down in tiny translation errors, okay?

Alpinesavvy tries not to offer advice, only ideas and information. I’m absolutely not saying that you should go out and start using these techniques tomorrow, especially without knowing the context and having appropriate instruction. I say again, having appropriate instruction. (Doing this may require a trip to Europe, lucky you.)

I'm not posting every graphic in the entire document, rather the ones I found personally interesting. I encourage you to check out the whole PDF file yourself; click the button below.

The title of the PDF: ”Standplatzlogik VDBS 2019 - Ausbildungsstandard VDBS & Alternativen”

This translates as “Belay stance logic - VDBS training standards and alternatives.” This title alone caught my attention. It's “Professional German Guide Training Standards”, not, “random stuff I saw on the Internet that might work for anchor building.” =^)

Let’s get to it!

Anchor 1 - Let's start off with something not familiar to Americans, a single bolt.

Yes, that's right, one bolt, no redundancy, that's all you got, better get comfortable with it. It's probably a glue in, it's probably about 20+ cm long, and you can probably hang a bulldozer off of it, but it's still one bolt.

It appears that the leader is cloved hitched directly to the yellow carabiner, and brings up the second with a Munter hitch on the black carabiner.

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS

Anchor 2 - Here's an anchor set up more familiar to the rest of the world, “two solid fixed points”

Do you see a sling, a quad, a cordelette, or any attempt at equalization? Nope! If you want to build an anchor using the rope, this is about as simple as it gets. All the load is obviously on the left bolt, with the right bolt only serving as a backup in the (1 in 100,000?) chance that the left bolt fails.

This reflects a different approach to anchor building in areas that have top-quality twin bolted anchors - there's really no need to try to equalize.

(Note, the rope is tied to the belay loop and not the harness tie in points. Not a standard practice in the US and not recommended by most harness manufacturers, but apparently acceptable to the VDBS, so in this case I'm gonna call it good.)

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS

Here's another approach, in the diagram on the right. Instead of clove hitch, you can make a bight knot and belay from that.

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS - https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rpPxbNOHjCQNFZmnI-qB9iEXun7Q4Qyf/view

Side note: Check out how the rope is tied to the harness in the diagram above: to the belay loop! This is definitely not standard practice in North America, but maybe in Germany?

Have a look at the screen grab below from the Edelrid website. It clearly shows that tying to the belay loop is acceptable.

image: https://media.edelrid.de/images/attribut/54507_GAL_Gurte_Sport_ANSICHT.pdf

Anchor 3 - The fixed point belay

Again, used with two solid bolts, and again, this puts all of the load on the left bolt with the right serving as backup. This time, instead of using the rope and two clove hitches to connect the bolts, you use a double length (120 cm) sling instead. The sling is tied with a double loop bowline on the left, and either a clove hitch with the end clipped, as shown on the left, or a simple overhand knot, as shown on the right.

This technique can be used here as shown, to bring up your partner(s), and it can also be used to belay the leader directly from the anchor. AlpineSavvy has a detailed article on the fixed point belay technique, read it here.

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS

In the right side margin is this text. It's highlighted, I'm guessing it's pretty important. =^)

Yellow: “Dyneema at the belay as linear connection sling with double bowline: width starting at 10 mm recommended (careful with older 6 or 8 mm slings) In red: “NO old dyneema slings with knots at the belay”

image credit: Chris Semmel / VDBS

Takeaway: (I would guess that the applies to using Dyneema slings for any kind of anchor, not just a fixed point as shown.)

Dyneema slings are fine to use when building an anchor.

It's best practice to use slings that are 10+ mm.

It's okay to put knots in them, provided the slings are relatively new.

Anchor 4 - Swinging leads with a rope anchor

Now, this is interesting. Lots of people think that if you build an anchor with the rope, you can’t block lead. You have to swap leads, because there's nowhere for the second to easily secure themselves.

Well, the set up below lets you swap leads!

It took me a minute or two to digest what was going on, look at the photo below and think it through. Using the quick draw on the top bolt is the key move.

This one is fairly complicated and definitely one to practice on the ground first!

Left: The second is belayed up on the light green rope with a munter hitch.

Center: The second clove hitches into the upper carabiner on the bottom bolt, removes the bottom carabiner, passes the rope behind the connection to the leader, and then clove hitches to the top carabiner of the quick draw.

Right: The leader is put on belay with a munter hitch from the bottom bolt, and clips the quick draw as the first piece for the next pitch.

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS

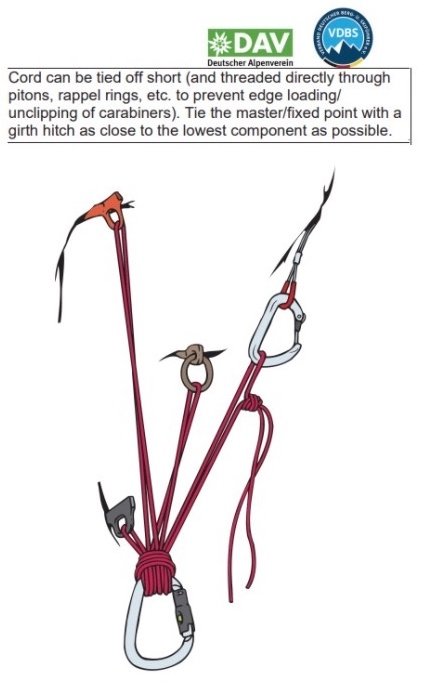

Anchor 5 -Now we're getting into alpine anchors, with “2 fragile fixed points”.

(See, your German is getting better already!) “Standard for load distribution.”

Notice, static equalization only. No sliding X, so no chance of suddenly loading the remaining anchor. An overhand knot on the left, and a girth hitch on the right. Yes, a girth hitch, it's fine to use that at the master point. Get used to it, you're about to see a few more. Learn more about the girth hitch master point here.

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS

Anchor 6 - Girth hitch on the ring at the top, pass a bight through the piton at the bottom, and then girth hitch the master point carabiner.

Many people would assume this anchor would require three carabiners, but in fact you only need one. You can rig this same anchor if you find yourself at a chain anchor and are low on carabiners; learn how from this article.

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS

Anchor 7 - Look, another girth hitch at the master point!

Also note, this is tied with an open, or untied cordelette. This lets you thread one end through the two pitons and the ring, and then re-tie the cord.

This can be a good method on rock that has a lot of fractures, pockets, or protrusions, because there are fewer carabiners that might be loaded sideways at strange angles.

Historical and geographical note, this style of anchor originated in the Dolomites in northern Italy, where there are lots of fixed pieces of gear in often marginal rock with lots of strange bumps and protrusions. This area is called the “Sud Tirol”, or South Tirol.

Can you see how the cord is tied into a loop? Looks like that's called in German a “paketknoten”, or “parcel knot” which is kind of a 1.5 overhand bend. (Personally I'm fine with a standard flat overhand bend here, although probably with slightly longer tails than what’s shown.)

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS

Here's a similar version, this time with a caption in English. (For any of you still wondering whether a girth hitch at the master point is a valid technique, hopefully you're convinced by now.) This is from a PDF file called: “Standplatzübersicht VDBS DAV 2020”

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS

Here’s how to tie the Paketknoten / parcel knot.

Anchor 8 - Hopefully you never have to make a five piece anchor, but if you do, you might want to remember this technique.

The clove hitches require a lot less cord compared to the traditional cordelette, where you’d have to pull down loops between each piece of gear.

(There’s a three-piece variation of this, called the “V clove” anchor, here's an article about it.)

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS

That's about all. Hopefully this may have broadened your perspective a bit on acceptable anchor building practices.

Again, anchors are often dependent on context and intended use, so it can be a bit tricky to extrapolate from a single diagram what are appropriate real world uses.

Please seek qualified instruction for learning critical skills like this.

And finally, if you've read this far, everyone has at one point wished for an octopus anchor =^)

image credit: Georg Sojer / Chris Semmel / VDBS - https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rpPxbNOHjCQNFZmnI-qB9iEXun7Q4Qyf/view

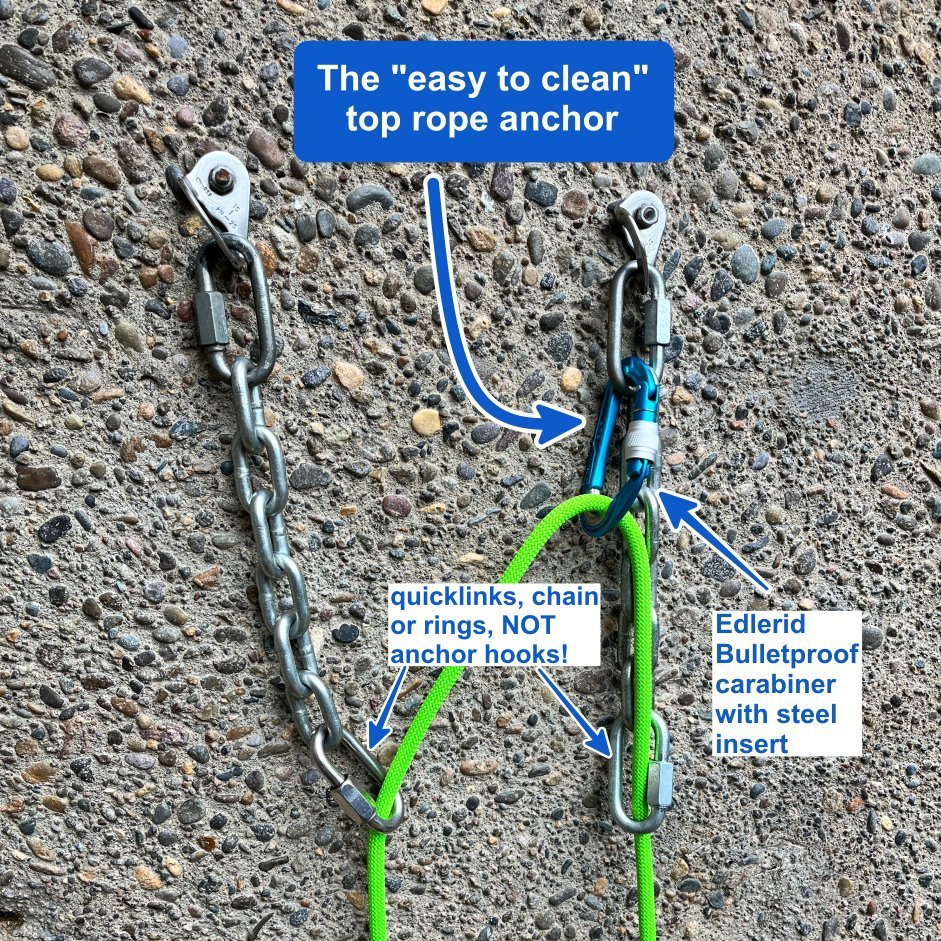

The "easy-to-clean" toprope anchor

Are you top rope climbing with someone who doesn't know how to clean and lower from an anchor? Here's a simple way to rig a top rope to make cleaning and lowering safe and simple for the last person.

Modern “clip & lower” anchor hardware like fixed steel carabiners and Mussy hooks allow faster and simpler transitions from climbing to lowering, and are a great development at many popular climbing areas. However, they are still catching on, and many routes will have a chain anchor without clip & lower hardware. That usually means you need to build your own anchor of some sort, because it’s generally bad practice top rope directly through the anchor hardware. (Hopefully you know that already . . .)

Typically, the most experienced person will lead the route, which means the beginner climbs second and cleans the anchor. Of course, learning to safely clean and lower is an important skill to learn eventually. But if you're climbing with someone who does not have it down, here’s a way to rig your anchor to keep it simple and low risk for the last person up.

Important cautionary note at the bottom of this article, please read all of it!

The first person leading the route, usually the most experienced, can rig the anchor is shown. You can now top rope off this anchor all day, and all the wear-and-tear from the rope goes your bottom carabiner, not on the fixed hardware.

If you’re toproping a lot, you might want to use steel carabiner or maybe the cool Edelrid “Bulletproof” carabiners. These are aluminum and have a steel insert at the bottom where the rope goes, meaning they will last much longer.

Notice how the carabiner is clipped through the quick link which means it's facing out, perpendicular to the rock. This can help minimize rope twists.

For the last person up (typically less experienced) to clean the anchor, it couldn’t be much easier. They simply clean the carabiner and call for a take and lower.

To clarify, lowering directly from the anchor chains is only for the LAST person, not everyone who’s top roping the route. Avoid top roping through fixed gear.

Concerns, grumbles, FAQ . . .

“You should never top rope through fixed gear.” That's generally true. It might seem like that's what's happening here, but it's not. As soon as the rope is weighted, all the force goes onto the carabiner and there's no significant wear on the rings.

“It’s not equalized.” That’s correct, because it doesn’t need to be. You're climbing on two modern bolts, each of which is rated to at least 25 kN. In the extremely unlikely (1 in 100,000?) event that the left bolt were to fail, the rope will be caught on the right bolt. (If equalization is important to you, simply clip a second carabiner into the quick link on the right side hanger.)

“If the bolt fails, it’ll shock load the other one. ” Not a concern. This is a top rope anchor with your stretchy dynamic rope absorbing almost all the force of the very modest fall, if a very unlikely bolt failure ever were to happen. (Again, if this concerns you, just clip a second carabiner to the right bolt.)

“Do I need a locker?” Not really. A standard snap gate carabiner is fine here. If the rope were to detach from the carabiner, it’s still going through the rings. But if it makes you happy to use a locker, go for it.

“Lowering through chains is bad, rappelling is better.” With modern anchor hardware that's inexpensive and easily replaceable, it’s now preferred practice (in most areas) for the last climber to lower, not rappel, from the anchor. This anchor is set up perfectly for that: large long-lasting 50 kN stainless steel rings at the bottom, connected to a quick link for easy replacement. This is per the recommendation of the American Alpine Club.

Caution: Don't do this on “open” anchor hardware (like anchor hooks)

This technique should only be used on “closed” anchor hardware, such as a ring, quick link, or chain, where there is no possibility of the rope coming unclipped. Do NOT use this technique on “open” anchor hardware, such as anchor (aka Mussy) hooks, carabiners, or a ram’s horn / pigtail.

In autumn 2023, there was a fatal accident in Alabama. It involved a beginning climber who was cleaning an anchor hook anchor, that had a locking carabiner added to minimize wear on the hooks. The carabiner was removed, somehow the rope unclipped from the hooks, and she fell.

Short version: for anchor hooks, do NOT add a carabiner on the anchor for the rope. If you do toprope through your own equipment, extend quick draws or slings BELOW the level of the hooks, and put the rope through your own gear that way. This reduces, but does not eliminate, the risk of the above accident happening again.

Also, NEVER have someone clean an anchor who is not 110% solid on the correct procedure. The proper learning sequence should be: 1) instruction on the ground, until the person can demonstrate several times in a row the correct sequence. Then, 2) doing it with an instructor off the ground, hanging at the actual anchor, where they can be directly supervised. (This means NOT yelling instructions from the base of the cliff!)

Here’s an analysis of the accident from IFMGA Certified Guide Karsten Delap.

Here's another video from Karsten showing some ways to build your own anchor with your own gear, and then transfer to the anchor hooks when it's time to lower off for the last person.

Printing backcountry maps in CalTopo

CalTopo is a top choice for backcountry mapping software for many reasons. One big one is the ease of printing. Let's have a closer look at some of the print features of CalTopo, some obvious and some a little more hidden.

CalTopo, my favorite backcountry mapping software, has a lot of great features. (While many of them are free, you can get a lot more with an annual subscription, which I strongly encourage you to do.)

One CalTopo highlight is superb map printing. Let's have a closer look.

1 - CalTopo generates a “geospatial” PDF

Rather than just spitting out a file to your printer, CalTopo generates a PDF file. (There is a JPG option, but I hardly ever use it.) This makes it easy to save the PDF to your computer, the cloud, and/or email it. This might sound like a trivial feature, but it's really handy. Tip - the “Generate PDF” button opens a new browser tab that shows the PDF. Remember to save or print this file; if you close the browser tab, it's gone and you have to generate it again. You can also save this PDF to your paid account, making it easy to share and organize.

Plus, it's not just a “dumb” PDF file, it's what's termed “geospatial”, or “geo-referenced”. This means that it has real world coordinates embedded in the file. This lets you to use the PDF map in various types of phone GPS apps, such as Avenza, as your base layer. (Personally this is not something I use, but some people find it handy.)

2 - Choose your paper size (depends on subscription level)

A free CalTopo account lets you print only on one paper size. But as you move up in subscription levels, it gives larger and larger printing options. At the basic $20 a year level, you can print on 11” by 17” paper, which is a very convenient size for lots of backcountry trips. By adjusting map scale to a custom number (such as using 1:30,000 rather than 1:25,000) and paper size, you can often print a map for a fairly large area on a single sheet of paper. (Pro and Desktop subscription levels allow printing on pretty much any size paper you want.)

3 - Print at any map scale you want

Many types of mapping software don't give you any option to choose the scale, and they don't tell you what scale the map is even when it does get printed. CalTopo does both. At the top left side of the print dialog box, there’s a dropdown for five or six common map scales. You can also choose your own, under “Custom”. (I often use this feature to make custom orienteering maps, which are often a 1:10,000 scale.)

4 - Choose your DPI (depends on subscription level)

DPI, or dots per square inch, determines the overall quality of your printed map. The default DPI is 200, which is fine for most weekend climbing and backpack trips. Higher subscription levels (Pro and Desktop) give you access to a 300 and 400 DPI option.

5 - Print a UTM or lat/long grid

Having a printed UTM grid on your map can be helpful for several things. It can help you estimate distance in kilometers, lets you plot UTM coordinates from a GPS onto your map, determine your UTM coordinates from your map, and give you a grid that's pretty closely aligned to true north, which can make measuring compass bearings on your map a bit more accurate. You can toggle this grid on or off with one click. I usually choose to have it on.

6 - Print multiple pages

One of the most powerful features in CalTopo is the ability to print multiple map pages, and do so in any combination of landscape or portrait that you want. For example, on a multi-day backpack trip you would probably need to print out several different pages to cover your trip at a reasonably large scale. If your trail runs north-south, you can print in portrait mode. If the trail changes to more east-west, you can print a few pages in landscape. Also, the red box that shows the actual print area is idiot proof and accurate. Click and drag the red print area boxes to determine how much overlap you have between map sheets.

7 - How to print it

Always protect a printed map from the elements. At the bare minimum, use a 1 gallon Ziploc freezer bag. Having the map in a plastic bag also makes it much more resistant to tearing.

It's best to print your map on a color laser printer if possible. Typically I save the map from my desktop computer onto a thumb drive, take the thumb drive to my local office store, and use the color laser printer there for a buck or two.

8 - Other helpful map information

On the bottom margin, CalTopo prints just enough info to be helpful, but not more than you need. You get a scale bar in miles and kilometers, the UTM zone, a ratio scale (like 1:25,000) the map datum (defaults to WGS84), and the correct magnetic declination for your location (declination is often incorrect on older printed maps).

One unique feature of CalTopo maps is a QR (Quick Read) code, printed on single page maps only. If you point your phone camera at the QR code, it can save the map as a PDF onto your phone, very cool! (You can even do this off of a computer screen, you don't even have to have the printed map in front of you.) This means one person can make a PDF map, email it to everyone else on the climbing team, and they then can print it, and/or save the map to the phone with the QR code. I'm a big fan of always carrying a digital backup of a paper map on my phone, and this is a super easy way to do it.

Here’s an example of the bottom of a CalTopo one page map, showing datum, UTM zone, two scale bars, ratio scale, QR code, and declination diagram.

Finally, here's an example of the finished product, for the Disappointment Cleaver route, Mount Rainier.

1:25,000 scale

11 x 17" paper (prints nicely on 1 page)

1 km UTM grid

MapBuilder Topo layer

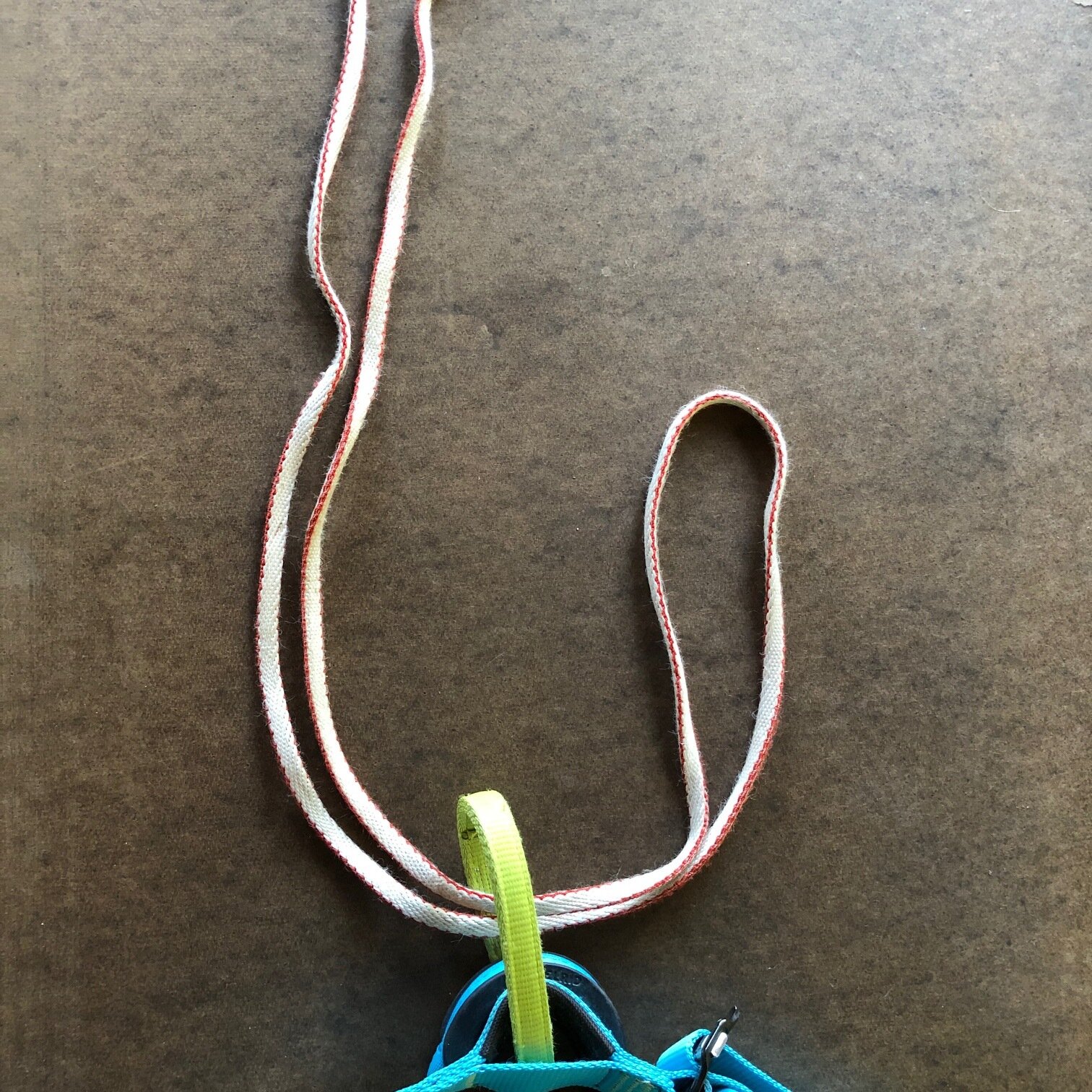

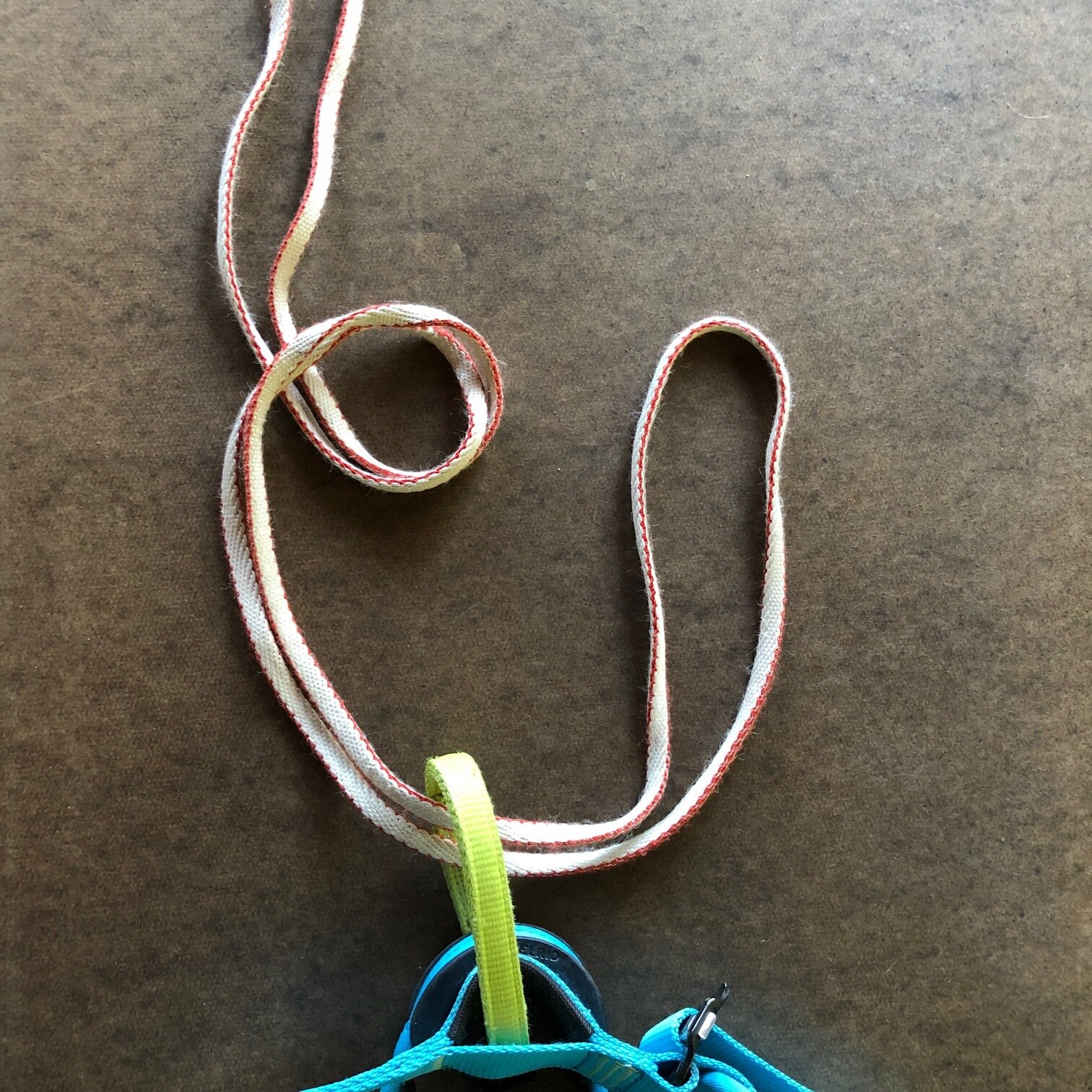

2mm cord cuts 9mm climbing rope

You don't need a knife to cut a rope. A few feet of very thin cord pulled through a rope under tension is all you need. Watch the video here.

You don't need a knife to cut (okay, melt) a climbing rope.

Take a meter or so of any kind of thin cord. In the video I'm using 2mm but I've also done it with 5mm.

Tie a bight knot in each end, clip the loops to carabiners for handles.

Rapidly saw back-and-forth through the material that's under some tension. You’ll cut it through in a few seconds.

Check out the message from an Instagram friend below, they used it to cut through a tether. Pretty much any cord can cut through any kind of soft good if you do it fast enough.

This should also be an outstanding reminder of one of the few “Nevers” in climbing: Never set up a top rope through any kind of cord or webbing. When you lower your partner off, all of that friction, and resulting heat, can potentially cut through or severely damage your anchor material!

This is more than a party trick. Here's a message I got the Instagram after I posted this.

BD Gridlock with Grigri - are you using it wrong?

The Black Diamond Gridlock carabiner is designed to minimize cross loading. When using this carabiner with a Grigri, Black Diamond recommends that you clip the wide part of the carabiner to your harness, and the narrow end to the belay device: opposite the normal way you would use a carabiner.

The Black Diamond Gridlock is a popular belay carabiner, because it has a clever mechanism that (in theory) prevents your carabiner from being cross loaded. You would think the narrow end with the clip around it should always be put in your belay loop, right?

Apparently, not always. At least, that what Black Diamond says.

Lucky for you, the Alpinesavvy web gnomes actually read instruction manuals from time to time, even for carabiners.

The following is a screen grab from a PDF from the Black Diamond website, which you can see here. (You'll either need a magnifying glass or hit “control +” on your keyboard about seven times to make it big enough to read.)

image: blackdiamondequipment.com

Check out the first two diagrams. With the tube style belay device and a munter hitch, Black Diamond wants you to clip the carabiner in the logical way, with the small side toward your belay loop.

But look at the third diagram, with a Grigri. According to this, you're supposed to turn the carabiner so the small side is AWAY from your belay loop.

I don’t work for Black Diamond, so I can’t comment on the exact reasons for this. But, judging from the last diagram on the right, it appears that cross loading is a concern. Keep in mind the whole point of using a carabiner like this is to avoid across loading . . .

(And yeah, it’s a bit odd that BD is telling you how to use a belay device made by Petzl, but that’s a different conversation.)

Alpinesavvy offers ideas and information, not advice. If you use a Gridlock carabiner with a Grigri, consider yourself informed as to what Black Diamond wants you to do. Following manufacturer recommendations is usually good practice. But, you're free to use your belay device any way you like.

Grigris for alpine climbing

Many climbers love their Grigri for sport climbing, but think that it's 1) too heavy and 2) single purpose to bring for a long alpine route. Is this really true? Let's take a closer look at why bringing a Grigri might be a smart move for alpine climbers.

Thanks to AMGA Certified Rock Guide and Assistant Alpine Guide Derek DeBruin for assistance with this article. Connect with Derek: Facebook and Instagram

Also, thanks to Blake Harrington for this article which covers some of the same key points made in this one.

Have you ever heard some version of this?

“Grigris are great for sport climbing, but not for alpine routes. They’re too heavy and single purpose.”

This a common dismissal from many climbers, but it really true? Let’s have a closer look at these objections and see some of the ways a Grigri (or similar assisted braking device, aka ABD) might just earn a place on your alpine harness.

Now to be clear I'm not saying a Grigri is always the best choice for every route that could be considered “alpine”. If you climb with double ropes, or in conditions where your ropes might get very wet or icy, a Grigri will probably stay at home. But for a team of two, with mostly rock climbing, with a single rope, it can be a pretty sweet setup.

(Yep, I know there are some cool belay devices such as Edelrid’s Giga Jul, Mammut’s Alpine Smart, etc. Today we’re talking about the Grigri.) We’ll cover some of those other devices in another article.)

North Ridge, Mt. Stuart, Washington. About 25 pitches, and a great route for a Grigri. Photo credit, Steph Abegg (used with permission). Steph has a SUPERB website with loads of great beta, annotated photos and trip reports, check it out!

North Ridge Mt Stuart. photo credit: StephAbegg.com

First, the “it’s too heavy” issue.

Well, check that out! A Grigri and one locker can actually be LIGHTER than a plaquette and two lockers!

Of course your real world weight is going to vary a bit depending on your belay device and carabiners, but we’re really only talking a few grams between different systems. Do you really think you're gonna notice that on your harness?

Okay, weight isn’t an issue. How about functionality?

A two person team climbing on a single rope with one Grigri and one plaquette style belay device (such as a DMM Pivot, my favorite) can have a lot of benefits. Some of them are pretty obvious, others perhaps not so apparent.

Wait a sec, I heard you shouldn’t a Grigri for trad climbing, because it increases forces on the top placement . . .

Good point! One possible concern with a Grigri and trad climbing is that the Grigri can put more force on the top piece of protection when catching a fall. The better question would be, how much extra force are we talking about, and is it concerning? Let’s check out the nice graph below from Petzl.

With a low fall factor of about 0.3, the difference is negligible. As fall factors increase past about 0.7, there can be an extra 2 Kn or so on the top piece of gear. So, we can see that the potential problem is not with the Grigri, but rather the fall factor.

If there’s a reasonable chance of a high factor fall (climbing is hard off of the belay and there's not many gear placements), there are various solutions. One simple one: the climbers switch devices just for that pitch.

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Influence-of-the-belay-device?ActivityName=Rock-climbing

1 - Reduces belay risk

With this system, typically the leader is always belayed with the Grigri and the second is always belayed with the plaquette in guide mode. On alpine routes where the belayer needs to use semi-downtime to change clothes, check the topo, grab some food/water, etc., you can be momentarily hands-free and still have a (fairly) secure belay. If you really need to go really hands-free, just tie a quick bight knot in the brake strand as a backup.

2 - Reduces rappel risk

At first glance, you might wonder how this system works for getting down, because the Grigri can only use one strand of rope. There are several different ways to descend with a Grigri - 1) fix one strand of rope, 2) self-lower, and 3) knot block. Of these, fixing a strand of rope will usually be the most practical.

With this system, the rope is threaded for a normal rappel, one strand gets fixed to the anchor, and the Grigri partner raps first. There are LOTS of ways to rig this. Here’s a simple method: add a locking carabiner to the master point and fix the rope with any sort of a bight knot. A Figure 8 or overhand is fine. In the example below I used a butterfly because it's often easier to untie after its been loaded.

The first person descending with the Grigri has a few advantages over a normal two strand rappel. They can go hands-free to to sort out rope clusters, find the next anchor, pendulum around if needed, and any other shenanigans that are less risky when you don’t have to always be concerned with keeping a tight grip on the brake strands. And, if the first person rappels too far past an anchor, the Grigri is easy to convert into an ascending system to go back up the rope, see next step.

If the wind is really whipping around, the first person can descend on a Grigri and can tie in to the end of both rope strands, keeping them under control and minimizing the chance they’re going to get blown around and cause problems.

Once the first climber is secure at the lower anchor, the second person unties the bight knot, removes the locking carabiner, and rappels normally on two strands with the plaquette.

Another approach, which can further increase speed and reduce risk, is for the second climber with the plaquette belay device to use an extended rappel and pre-rig their device on the rope. If after doing this they add a third hand autoblock under their device, both strands of the rope are essentially locked in place. The first person with the Grigri can descend on either strand.

Note: Many people think that simply pre-rigging is enough to lock the rope in place for the first person down. This is not always the case. If you have a smaller diameter, slick sheathed rope, a heavier first person, minimal friction from rock, etc., the rope can start to slowly creep through the device. Adding the auto block stops this from happening. You could also stop any “rope creep” by tying a Stone hitch or a BHK (overhand on a bight in both strands) below the rappel device.

As with all new rappelling systems, always practice in a controlled environment before you ever try it on real rock.

3 - Simplified belay changeovers

When the second arrives at the anchor, they are already secure on the plaquette, so there's no real need to clove hitch to the anchor, use a PAS/tether, etc. ( At an exposed stance, the leader can add a quick bight knot on the brake strand for some extra security if needed.) If you're swapping leads, the new leader racks up, gives their Grigri to the previous leader, goes on belay, cleans the plaquette device and carabiners, and begins the next pitch. Simple, efficient changeover.

4 - Easy rope ascending

If the second needs to ascend a fixed rope, it’s easy to rig an efficient system with the Grigri, a small ascender such as a Petzl Tibloc and a double length runner as a foot loop. (Or a regular handled ascender and pre-tied webbing foot loop if you think you’re going to be doing it a lot.) In low angled alpine terrain, you may not even need the Tibloc; just push off the wall with your feet to make upward progress.

On a hard alpine route, especially if you have a rope gun, it might end up to be faster to have your stronger climber lead the really hard pitches, and the second ascending directly on the rope, just like on a big wall.

Here’s an article with complete details and video examples of how to do this.

5 -Simul climbing (for advanced climbers only!)

You know those expert teams climbing El Capitan in a few hours, who are pretty much always in motion and never really stop to belay? The second climber is almost always attached with a Grigri (as well as being tied into the end of the rope.)

You don't have to be a Yosemite speed climber for this technique to be effective. Long, moderate routes such as the 25+ pitch North Ridge of Mt. Stuart (photo at top) can be ideal for this, provided you and your partner are solid and experienced with the techniques.

The Grigri lets the second quickly feed out or take in a rope as necessary. Being able to fine tune the amount of rope between the second and the leader can be a tremendous help when simul climbing. Is the leader moving faster than you are? Throw them some slack through the Grigri. Is the leader slowing down and you’ve got a big loop of slack in front of you? No problem, pull that slack back through the device. (A kiwi coil, if you have the free hands to make one, to take up slack can be a good idea on lower angle terrain, so you don't trip on the rope.) You get the idea.

If the leader needs a proper belay through a few hard moves, the second can climb up to the next protection, or place some where they are, and give a proper lead belay. If the leader is using a progress capture device such as a Tibloc or Ropeman on the pro, it would be a fine idea to add this in after, not before, the hard moves. (In case you're wondering, this is a legit technique, read more about it here.)

These few suggestions are just scratching the surface of a very advanced application. If you want to learn the nuances of simul climbing, I highly recommend professional instruction from a certified guide.

So, that's my take on using a Grigri in the alpine. There is no significant weight penalty, and it's useful for a lot more than just belaying. If you’ve never rappelled on one or used it as an ascender, please practice in a controlled environment with a competent instructor before you ever do it for real on a big route.

"Summit flattening" in Google Earth